The etiology and epidemiology of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy remain uncertain. The symptoms of this condition are often similar to those of myocardial infarction and, although it usually has a good prognosis, it is not without complications. Our aim was to characterize this disease in our setting using a dedicated registry (Spanish REgistry for TAKOtsubo cardiomyopathy).

MethodsThe prospective registry included 202 incident patients in 23 hospitals from 2012 to 2013. The patients’ clinical characteristics and analytical, echocardiographic, and imaging results were recorded, as were the events during follow-up. Patients were included when the attending physician considered the case proven, and incidence was calculated relative to the catheterizations requested for a presumptive diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome.

ResultsThe patients were predominantly women (90%), with a mean age of 70 years, and many had cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension (67%), dyslipidemia (41%), diabetes mellitus (15%), and smoking (15%). The incidence of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy was 1.2%, and there was no clear weekly or seasonal distribution pattern. Chest pain was the predominant symptom, a triggering factor (emotional, physical, or both) was present in 72%, and most patients consulted within the first 6h after symptom onset. The median duration of hospitalization was 7 days. There were heart failure symptoms in 34.0%, arrhythmia in 26.7%, and 2.4% of patients died.

ConclusionsThe incidence of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy is low. This disease primarily affects postmenopausal women, and occurs after a situation of emotional stress in more than half of affected individuals. It is characterized by anginal pain, shows no seasonal distribution, and has a good prognosis, although it is not without morbidity and mortality.

Keywords

In 1990 in Japan, a syndrome was described consisting of chest pain, electrocardiographic and biochemical changes similar to those seen in acute myocardial infarction, and abnormalities of left ventricular apical contractility.1 The peculiarity of this new disease, which was first attributed to multivessel spasm, was that the coronary arteries showed no lesions and the marked abnormalities of ventricular segments virtually resolved within a few days or weeks.1,2 The syndrome was named tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), apical ballooning, or transient apical dyskinesia. Compared with classic coronary syndromes, TCM is notable for regional involvement of various coronary territories and its excellent ultimate prognosis.2,3 Nonetheless, although it is usually a benign condition, it is not without complications. The most common of these are heart failure, arrhythmia, intraventricular thrombi, and even death, mainly occurring in the acute phase.4

Various groups from Spain and other countries have reported case series consistent with these features,1–6 including a description of the first series in Spain of the midventricular variant,7 which is also recognized outside our country.3 Other related articles from Spain have described patients with predominantly inferior ventricular involvement, and one has proposed the theory that the condition coincides with chronic ischemic heart disease.8 Some authors have focused on the relationship between the left ventricular hypertrophy and the mid- to long-term outcome of these patients,4 which may not be as benign as that of other patients with hypertrophic ventricles.9 In addition, Spanish researchers have intensively investigated the pathophysiology of the syndrome and have proposed some interesting theories in this line, such as a wraparound left anterior descending artery,5 or an effect of the intraventricular pressure gradient.9 Other studies have compared the electrocardiographic findings according to race.6,10

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiopathogenesis of TCM.11–14 Although it remains to be clarified, there seems to be an important relationship between the development of this syndrome and an excess of circulating catecholamines resulting from a situation of emotional or physical stress.4,11 Nonetheless, the definitive cause of TCM is uncertain and precise epidemiologic data on this condition are not available in Spain, as most of the published articles report the experience of one or only a few centers.

The aim of this study was to create a collaborative, multicenter national registry of TCM cases with a view to describing this disease in more detail in our setting.

METHODSThe multicenter Spanish REgistry for TAKOtsubo cardomyopathy (RETAKO), created under the auspices of the Ischemic Heart Disease and Cardiovascular Acute Care Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, is a prospective, voluntary, national registry. It includes patients who meet the criteria for this disease (based on the modified Mayo criteria15) in the opinion of the attending physicians, as reported previously.4 The present analysis included data on TCM patients consecutively hospitalized from (and including) 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2013, provided by 23 hospitals throughout the country (Table 1). The number of patients with this condition relative to the number of coronary angiographies requested in each hospital for the working diagnosis (subsequently confirmed or not) of acute coronary syndrome was calculated to determine the approximate incidence of this disease in our setting. The Registry collected information on the patients’ clinical characteristics, complications during hospitalization, analytical results, and findings on electrocardiography, echocardiography, and other imaging techniques (magnetic resonance imaging was optional in the protocol). Initially, this information was recorded on a case report form and sent by e-mail to a data processing center, whereas later (after 2014), it was directly recorded on an on-line case report form. Some variables with aspects that were difficult to systematize were recorded on an open text field. To be included in the Registry, patients had to have undergone invasive coronary angiography that excluded significant obstructive lesions (> 50%) and any other potential cause of the clinical symptoms (eg, thrombus, dissection, ulcer). The treatment prescribed was always at the discretion of the attending physicians. At least 2 follow-up visits were recommended, one at 3 months and another at 1 year following the index event. Complete resolution of the regional wall motion abnormalities by any imaging technique was required, except in cases of death before the visit. The objectives investigated over follow-up were cardiovascular death, death due to any cause, and the need for readmission for any cause in a cardiology service. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos, and patients gave informed consent to participate in the Registry.

Hospitals That Included Patients Between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2013

| Patients includeda | |

|---|---|

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madridb | 33 |

| Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilleb | 22 |

| Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | 21 |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca | 21 |

| Hospital de Sant Pau, Barcelona | 17 |

| Hospital de la Princesa, Madridb | 14 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Albaceteb | 14 |

| Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Leridab | 9 |

| Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa, Zaragozab | 8 |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 6 |

| Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia | 6 |

| Hospital Carlos Haya, Malaga | 5 |

| Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid | 5 |

| Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid | 3 |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madridb,c | 3 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real | 3 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña | 3 |

| Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona | 2 |

| Hospital da Costa, Burela, Lugob | 2 |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madridb | 2 |

| Hospital de Manacor, Balearic Islands | 1 |

| Hospital Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madridb | 1 |

| Hospital Clínico de Valencia, Valencia | 1 |

| Total | 202 |

Statistical processing was done with SPSS version 20.0 (IBM SPSS; United States) and the multimedia software package, Office 2010 (Microsoft; United States). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or the median (range), depending on their distribution and dispersal. This is mainly a descriptive study, and between-group differences were analyzed using the appropriate statistical method according to whether quantitative or qualitative variables were included, as specified in the text. In the statistical analysis, significance was set at a bilateral P value < .05.

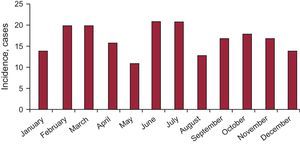

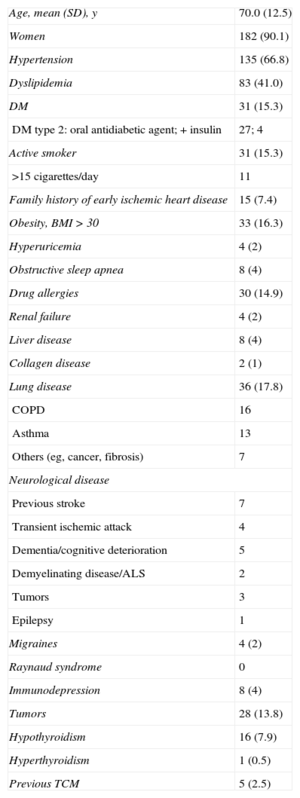

RESULTSPatient Profile and EpidemiologyA total of 202 patients were included, with a mean (SD) age of 70.0 (12.5) years. The sample was predominantly comprised of women (90.1%), and 98% of participants were white. The epidemiologic profile of the patients studied is shown in Table 2. The incidence calculation was performed using the number of patients undergoing coronary angiography with a presumptive diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (of any type, with or without biomarker elevation) in the hospitals providing data (Table 1) with respect to those patients with a final diagnosis of TCM in these same centers (108 of 8950) during the study period. This yielded an estimated incidence of TCM of 1.2%. No significant differences were found between the seasonal, monthly (Figure 1), or daily incidences.

General Epidemiologic Profile of Patients Recorded in Spanish REgistry for TAKOtsubo Cardiomyopathy (n=202)

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.0 (12.5) |

| Women | 182 (90.1) |

| Hypertension | 135 (66.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 83 (41.0) |

| DM | 31 (15.3) |

| DM type 2: oral antidiabetic agent; + insulin | 27; 4 |

| Active smoker | 31 (15.3) |

| >15 cigarettes/day | 11 |

| Family history of early ischemic heart disease | 15 (7.4) |

| Obesity, BMI > 30 | 33 (16.3) |

| Hyperuricemia | 4 (2) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 8 (4) |

| Drug allergies | 30 (14.9) |

| Renal failure | 4 (2) |

| Liver disease | 8 (4) |

| Collagen disease | 2 (1) |

| Lung disease | 36 (17.8) |

| COPD | 16 |

| Asthma | 13 |

| Others (eg, cancer, fibrosis) | 7 |

| Neurological disease | |

| Previous stroke | 7 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 4 |

| Dementia/cognitive deterioration | 5 |

| Demyelinating disease/ALS | 2 |

| Tumors | 3 |

| Epilepsy | 1 |

| Migraines | 4 (2) |

| Raynaud syndrome | 0 |

| Immunodepression | 8 (4) |

| Tumors | 28 (13.8) |

| Hypothyroidism | 16 (7.9) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 (0.5) |

| Previous TCM | 5 (2.5) |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; TCM, tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy; SD, standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as No. (%) or mean (standard deviation).

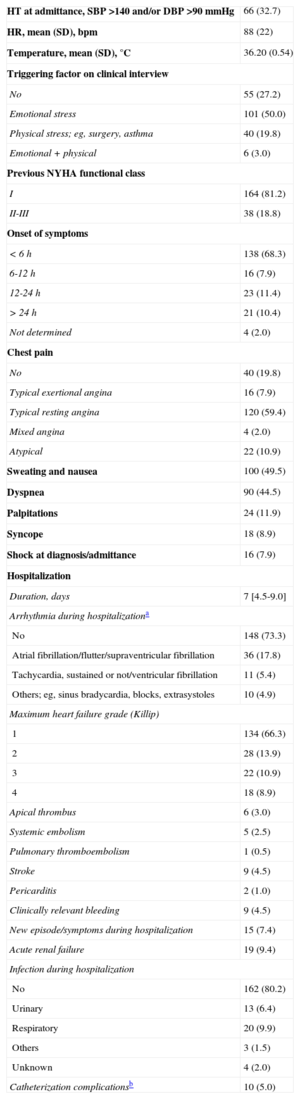

The main reason for consulting was chest pain, present in 162 (80.1%) patients, most of whom had good previous functional status (81.2% in class I). In general, the symptoms led to a prompt consultation: 138 (68.3%) patients came to the hospital within 6h after onset and only 10% consulted after 24h. Among the total, 72.8% reported a situation that might trigger or favor the syndrome, such as intense emotional stress, which occurred in 101 patients (50%). The mean duration of hospitalization was 8.2 (median, 7) days. Details of these aspects are summarized in Table 3. The patients’ treatment before and during hospitalization, and at hospital discharge are presented in Table 4.

Clinical Parameters and Hospital Stay (n=202)

| HT at admittance, SBP >140 and/or DBP >90 mmHg | 66 (32.7) |

| HR, mean (SD), bpm | 88 (22) |

| Temperature, mean (SD), °C | 36.20 (0.54) |

| Triggering factor on clinical interview | |

| No | 55 (27.2) |

| Emotional stress | 101 (50.0) |

| Physical stress; eg, surgery, asthma | 40 (19.8) |

| Emotional + physical | 6 (3.0) |

| Previous NYHA functional class | |

| I | 164 (81.2) |

| II-III | 38 (18.8) |

| Onset of symptoms | |

| < 6 h | 138 (68.3) |

| 6-12 h | 16 (7.9) |

| 12-24 h | 23 (11.4) |

| > 24 h | 21 (10.4) |

| Not determined | 4 (2.0) |

| Chest pain | |

| No | 40 (19.8) |

| Typical exertional angina | 16 (7.9) |

| Typical resting angina | 120 (59.4) |

| Mixed angina | 4 (2.0) |

| Atypical | 22 (10.9) |

| Sweating and nausea | 100 (49.5) |

| Dyspnea | 90 (44.5) |

| Palpitations | 24 (11.9) |

| Syncope | 18 (8.9) |

| Shock at diagnosis/admittance | 16 (7.9) |

| Hospitalization | |

| Duration, days | 7 [4.5-9.0] |

| Arrhythmia during hospitalizationa | |

| No | 148 (73.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter/supraventricular fibrillation | 36 (17.8) |

| Tachycardia, sustained or not/ventricular fibrillation | 11 (5.4) |

| Others; eg, sinus bradycardia, blocks, extrasystoles | 10 (4.9) |

| Maximum heart failure grade (Killip) | |

| 1 | 134 (66.3) |

| 2 | 28 (13.9) |

| 3 | 22 (10.9) |

| 4 | 18 (8.9) |

| Apical thrombus | 6 (3.0) |

| Systemic embolism | 5 (2.5) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 1 (0.5) |

| Stroke | 9 (4.5) |

| Pericarditis | 2 (1.0) |

| Clinically relevant bleeding | 9 (4.5) |

| New episode/symptoms during hospitalization | 15 (7.4) |

| Acute renal failure | 19 (9.4) |

| Infection during hospitalization | |

| No | 162 (80.2) |

| Urinary | 13 (6.4) |

| Respiratory | 20 (9.9) |

| Others | 3 (1.5) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.0) |

| Catheterization complicationsb | 10 (5.0) |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; HT, hypertension; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation

Treatment Before and During the Index Admission, and at Discharge

| Treatment | Previous | Admission | At discharge |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | 34 (16.8) | 185 (91.6) | 126 (62.4) |

| Clopidogrel or similar | 6 (3.0) | 152 (75.2) | 24 (11.9) |

| Anticoagulant | 22 (10.9) | 153 (75.7) | 36 (17.8) |

| Nitrates | 6 (3.0) | 76 (37.6) | 10 (5.0) |

| Diuretics | 55 (27.2) | 82 (40.6) | 56 (27.7) |

| Statins | 59 (29.2) | 149 (73.8) | 120 (59.4) |

| Beta-blockers | 18 (8.9) | 160 (79.2) | 147 (72.8) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 23 (11.4) | 20 (9.9) | 14 (6.9) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 102 (50.5) | 153 (75.7) | 143 (70.8) |

| Corticosteroids | 10 (5.0) | 16 (7.9) | 12 (5.9) |

| Anxiolytics | 58 (28.7) | 121 (59.9) | 69 (34.2) |

| Antidepressive agents | 38 (11.4) | 37 (18.3) | 39 (19.3) |

| Oral antidiabetics | 23 (11.4) | 8 (4.0) | 24 (11.8) |

| Insulin | 5 (2.5) | 21 (10.4) | 9 (4.9) |

| Amiodarone/dronedarone | 3 (1.4)/0 (0.0) | 7 (3.4)/0 (0.0) | 4 (1.9)/2 (0.0) |

| Inotropes (catecholamines) | — | 24 (11.9) | — |

| Levosimendan | — | 1 (0.5) | — |

| Balloon pump | — | 5 (2.5) | — |

| Noninvasive ventilation | — | 17 (8.4) | — |

| Invasive ventilation (OTI) | — | 17 (8.4) | — |

| GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors | — | 1 (0.5) | — |

| Thrombolysis | — | 6 (3) | — |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; GPIIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; OTI, orotracheal intubation. Values are expressed as No. (%).

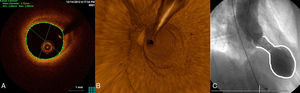

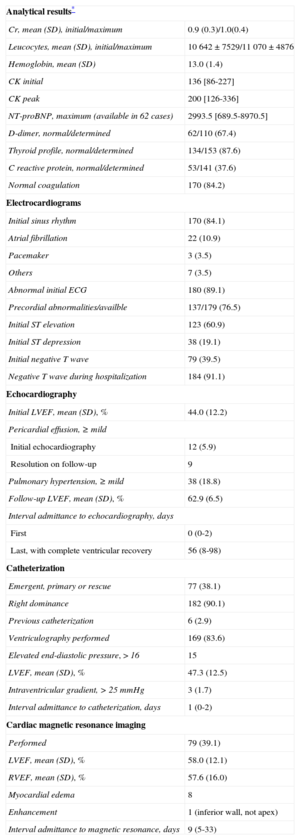

The analytical and electrocardiographic findings and the most relevant data from serial echocardiography and coronary angiography are shown in Table 5. One of the inclusion criteria was positive testing for biomarkers of myocardial necrosis (troponin T or I; a normal creatine kinase concentration was allowed). Nonetheless, the levels observed were notably low. On electrocardiogram, patients generally showed sinus rhythm (83.7%), and anomalies were common (89.1%) starting with the first tracing (Figure of supplementary material). The abnormalities seen were mainly in the precordial leads; 61.8% of patients showed ST-segment elevation in at least 1 lead. A negative T wave was seen in 39.5% on the initial test and in up to 94.4% at later testing. This finding explained the frequent development of a corrected (lengthened) QT interval (QTc), defined as > 450ms duration, which was observed in 130 of 165 patients (78.8%) (maximum QTc was not determined in 37). The mean QTc interval was 501 (73) ms. There were 2 episodes of torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia (1%), one with a long QTc (620ms), which progressed to ventricular fibrillation, and another in a patient with a pacemaker that abated with an increase in the pacing rate to 80 bpm. Among patients in the Registry with a known maximum QTc value, comparison of those with some type of ventricular tachycardia (sustained or not) and the remainder showed no significant differences (Fisher test, P = .34). Nonetheless, although ventricular tachycardia was uncommon (4.8%), all cases occurred in the group of patients with a long QT interval. The left ventricular ejection fraction measured by transthoracic echocardiography was 44.01 (12.28)% at the initial evaluation and 63.17 (7.3)% during follow-up (determined a median of 56 days following admission). Coronary catheterization, carried out on an emergency basis (for primary or rescue coronary angioplasty) in 38.0% of cases, showed a right dominance in 90.1%. Invasive coronary angiography, performed in 100% of cases, ruled out coronary vasculature abnormalities that could be a potential cause of the symptoms (Figure 2). Mean left ventricular ejection fraction determined by ventriculography was 47.27 (12.48)%. As to other diagnostic tests, magnetic resonance imaging was performed at some point during follow-up (median, 9 days; interquartile range, 5-33 days) in 79 patients, 40% of the total. None of the patients underwent a coronary vasospasm provocation test.

Additional Tests (n=202): Analyses, Electrocardiography, and Imaging

| Analytical results* | |

| Cr, mean (SD), initial/maximum | 0.9 (0.3)/1.0(0.4) |

| Leucocytes, mean (SD), initial/maximum | 10 642±7529/11 070±4876 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD) | 13.0 (1.4) |

| CK initial | 136 [86-227] |

| CK peak | 200 [126-336] |

| NT-proBNP, maximum (available in 62 cases) | 2993.5 [689.5-8970.5] |

| D-dimer, normal/determined | 62/110 (67.4) |

| Thyroid profile, normal/determined | 134/153 (87.6) |

| C reactive protein, normal/determined | 53/141 (37.6) |

| Normal coagulation | 170 (84.2) |

| Electrocardiograms | |

| Initial sinus rhythm | 170 (84.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 22 (10.9) |

| Pacemaker | 3 (3.5) |

| Others | 7 (3.5) |

| Abnormal initial ECG | 180 (89.1) |

| Precordial abnormalities/availble | 137/179 (76.5) |

| Initial ST elevation | 123 (60.9) |

| Initial ST depression | 38 (19.1) |

| Initial negative T wave | 79 (39.5) |

| Negative T wave during hospitalization | 184 (91.1) |

| Echocardiography | |

| Initial LVEF, mean (SD), % | 44.0 (12.2) |

| Pericardial effusion, ≥ mild | |

| Initial echocardiography | 12 (5.9) |

| Resolution on follow-up | 9 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, ≥ mild | 38 (18.8) |

| Follow-up LVEF, mean (SD), % | 62.9 (6.5) |

| Interval admittance to echocardiography, days | |

| First | 0 (0-2) |

| Last, with complete ventricular recovery | 56 (8-98) |

| Catheterization | |

| Emergent, primary or rescue | 77 (38.1) |

| Right dominance | 182 (90.1) |

| Previous catheterization | 6 (2.9) |

| Ventriculography performed | 169 (83.6) |

| Elevated end-diastolic pressure, > 16 | 15 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 47.3 (12.5) |

| Intraventricular gradient, > 25 mmHg | 3 (1.7) |

| Interval admittance to catheterization, days | 1 (0-2) |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Performed | 79 (39.1) |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 58.0 (12.1) |

| RVEF, mean (SD), % | 57.6 (16.0) |

| Myocardial edema | 8 |

| Enhancement | 1 (inferior wall, not apex) |

| Interval admittance to magnetic resonance, days | 9 (5-33) |

Cr, creatinine; CK, creatine kinase; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction.

Values are expressed as No. (%), median [interquartile range] or median (range).

Typical imaging findings. A: optical coherence tomography examination of the left anterior descending artery in 1 case. Image taken at the midarterial level shows an adequate minimal lumen area (5.82mm2). Note the atherosclerotic plaque on the vessel wall, particularly at the 11 to 4 o’clock position, which does not affect the lumen. B: 3-dimensional optical coherence tomography reconstruction in approximately the same area. There are no obstructive lesions or plaque rupture along the length of the vessel. The guideline image is seen at approximately 12 o’clock and the vessel ostium at the bottom. C: ventriculography in systole shows the typical “octopus trap” shape (“tako-tsubo” in Japanese).

The median follow-up was 3.20 [1.42-5.61] months. One patient, aged 51 years, was diagnosed with pheochromocytoma after inclusion in RETAKO, but was maintained in the analysis because of her typical pattern. She underwent surgery some months later, with no disease recurrence. All 5 deaths took place during hospitalization. There were no deaths during follow-up. Symptom recurrence (chest pain) was recorded in 2 patients, and the combined variable (cardiology readmission, recurrent symptoms, and/or death) was documented in 13 patients. Admissions for other reasons (eg, general surgery or respiratory infection) were not considered adverse events (Table 6).

Follow-up and Mortality (n=202)

| Clinical follow-up, months | 3.20 (1.42-5.61) |

| Deathsa | 5 (2.4) |

| Tamponade, possible cardiac ruptureb | 1 |

| Combined variablec | 13 (6.4) |

| Tako-tsubo recurrence requiring hospitalization | 0 |

| Recurrence of symptoms | 2 (1) |

| Re-admittance in cardiology department | 6 (3) |

| Follow-up NYHA functional class (assessable) | |

| I | 162 (82.2) |

| II | 30 (15.2) |

| III | 5 (2.5) |

GPIIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median (range).

The RETAKO is the largest TCM series compiled in Spain, containing first-hand information from the physicians treating these patients. Despite the limitations associated with a disease having a very low incidence and cases scattered across the country, the registry data provide a very close idea of the epidemiology of TCM in our setting. The characteristics of our patients are quite similar to those reported in series from other geographic areas.12,15–22 There is a predominance of hypertensive, postmenopausal women, and the common complications during admission include heart failure, arrhythmias (mainly supraventricular, but also ventricular), renal failure, iatrogenic complications, and others derived from the comorbidities.4 Although an outcome analysis was not the aim of this study because of the short follow-up period, we observed a generally favorable outcome following hospital discharge, as described in other studies.4

The etiopathogenesis of TCM remains speculative. Despite some evidence from intracoronary imaging,23,24 angiographically-silent plaque rupture as a causal possibility is uncertain; hence, a number of etiologies have been suggested for the syndrome.4 One of the most widely accepted theories in the scientific community for the transient ventricular dysfunction is the influence of catecholamines and the distribution of myocardial beta-receptors.11,12 Other hypotheses have recently been proposed, such as microcirculation vasospasm, based on a detection of an endothelin-1 abnormality.25 The contribution of this factor is difficult to reliably define; further knowledge of the disease is needed to definitively confirm this possibility.

The information derived from this registry and previous series gives the impression that the syndrome known as TCM may be a catch-all encompassing quite varied origins from a situation of myocardial stunning. Cases have been described in almost every imaginable circumstance involving stress, including the classic grieving for the death of a loved one, a fall with inability to get up for some hours, an asthma attack, pulmonary embolism, surgery, dysthyroidism, cerebrovascular disease, and even catecholamine administration during stress testing.16,26,27 Other pertinent questions also require clarification: why is it that not all people who go through stressful situations experience the syndrome? and Why is it that people who have had one episode of TCM do not have another in new situations of intense stress? (recurrence is uncommon).

Moreover, in a considerable number of cases (40-50%) in our series and in the literature, no potential triggering factor could be identified even after careful questioning. Could these be a primary form? This might be relevant from the prognostic standpoint, since it seems that patients with more severe diseases or comorbidities (secondary forms?) may have a poorer outcome, with the underlying or concomitant disease being the determinant of the poorer prognosis.28 At this time, however, it is difficult to say whether the prognosis is marked by the comorbidities or the triggering factors, although it is likely that both play a part. It is important to interpose this consideration in the decision of where to hospitalize the patient. If there are no comorbid conditions (or “secondary” form), the clinical status is good, and the ventricular dysfunction and biomarker elevations are not severe, it may be a safe choice to admit the patient for a few days to a hospital ward. In our cohort, 4 of the 5 deaths were due to causes unrelated to TCM. Of course, this reflection should be confirmed in larger TCM series with rigorous data collection. In summary, TCM has gained sufficient importance in recent years to merit a place in several clinical guidelines; for example, the European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of 2012, in which it still appears as an unclassified cardiomyopathy.29 In this line, RETAKO will continue its activity, attempting to respond with greater accuracy to the questions that arise about this enigmatic disease or group of diseases.

LimitationsThe limitations of this study include the logistical constraints of the study design and a disease having a relatively low incidence. It is possible that some incident cases in the participating hospitals were not diagnosed, were hospitalized in other specialty departments, did not undergo catheterization, did not have elevated troponin levels, did not accept to participate, or were not notified to the Registry, which would imply underestimation of the true number of TCM cases that occurred over the study period. The incidence calculation was adjusted by the number of coronary angiographies requested for an acute coronary syndrome, and it was not possible to relate the number of TCM to the total number of acute coronary syndromes. This, however, does not depart greatly from daily clinical practice, where coronary angiography is performed increasingly more often in patients with a suspected acute coronary syndrome (updated information on this is available in the DIOCLES registry30); hence, the analysis still provides a good idea of the size of the problem involving this condition. In addition, most of the participating centers are equipped with highly sensitive (or ultrasensitive) techniques for determining troponin I or T, but because the Registry includes patients from many different hospitals, the heterogeneity made comparisons impossible. The creatine kinase values are presented in Table 5 with the purpose of orienting the reader. Lastly, the coronary angiographies and remaining tests were interpreted by investigators from each of the centers; reading by a centralized laboratory was not carried out.

CONCLUSIONSTako-tsubo cardiomyopathy is an uncommon disease that predominantly affects postmenopausal women and occurs following an emotionally stressful situation in half the cases. It is generally characterized by anginal chest pain and shows no weekly or seasonal distribution pattern. The acute phase is not without complications or mortality, but once it has passed, the condition usually has a favorable outcome.

FUNDINGThis project was partially funded by a grant from the FMMA (Fundación Mutua Madrileña Automovilista). The electronic case report form and the RETAKO website31 were funded by AstraZeneca.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The authors thank all the RETAKO investigators and the institutions that have made this study possible.

Hernán D. Mejía, Gisela I. Feltes Guzmán and Corina Biagioni (Instituto Cardiovascular, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid); Juan Carlos García Rubira (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville); Jaume Figueras and José Barrabés (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona); Pedro Luis Sánchez and Javier Jiménez Candil (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca); Alberto Duran Cambra (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Sant Pau, Barcelona); Álvaro Lozano (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid); Miguel Corbí Pascual (Servicio de Cardiología, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Albacete); Ramón Bascompte and Fernando Worner (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lerida); José Ramón Ruiz Arroyo (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza); Martín Jesús García González (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife); Oscar Fabregat Andres and Francisco Ridocci-Soriano (Servicio de Cardiología, Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); Beatriz Pérez and Manuel de Mora Martín (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga); Juan María Escudier Villa (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid); Roberto Martin Reyes, Álvaro Aceña and Hans Paul Gaebelt (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid); Alberto Pérez Castellanos (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); Jesús Piqueras Flores, Andrea Moreno Arcinegas, Jaime Benítez Peyrat, Álvaro-León Moreno Reig and Luis Ruiz Valdepeas Herrero (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real); Cristina Cambeiro, José María García Acuña, and Milagros Pedreira Pérez (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña); Ferrán Rueda Sobella and Irene Santos Pardo (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona); Rafael Vidal Pérez (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital da Costa, Burela, Lugo); Javier García (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); Bernardo García de la Villa Redondo and Germán Alberto Madoz Peruzzo (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Manacor, Baleares); María del Carmen Manzano Nieto (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madrid); Vicente Bodí and Ernesto Valero Picher (Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico de Valencia, Valencia).