To evaluate the interaction between comorbidity burden and the benefits of in-hospital revascularization in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS).

MethodsThis retrospective study included 7211 patients aged ≥ 70 years from 11 Spanish NSTEACS registries. Six comorbidities were evaluated: diabetes, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal failure, and anemia. A propensity score was estimated to enable an adjusted comparison of in-hospital revascularization and conservative management. The end point was 1-year all-cause mortality.

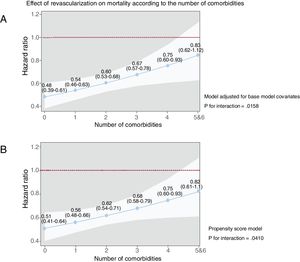

ResultsIn total, 1090 patients (15%) died. The in-hospital revascularization rate was 60%. Revascularization was associated with lower 1-year mortality; the strength of the association was unchanged by the addition of comorbidities to the model (HR, 0.61; 95%CI, 0.53-0.69; P=.0001). However, the effects of revascularization were attenuated in patients with renal failure, peripheral artery disease, and chronic pulmonary disease (P for interaction=.004, .007, and .03, respectively) but were not modified by diabetes, anemia, and previous stroke (P=.74, .51, and .28, respectively). Revascularization benefits gradually decreased as the number of comorbidities increased (from a HR of 0.48 [95%CI, 0.39-0.61] with 0 comorbidities to 0.83 [95%CI, 0.62-1.12] with ≥ 5 comorbidities; omnibus P=.016). The results were similar for the propensity score model. The same findings were obtained when invasive management was considered the exposure variable.

ConclusionsIn-hospital revascularization improves 1-year mortality regardless of comorbidities in elderly patients with NSTEACS. However, the revascularization benefit is progressively reduced with an increased comorbidity burden. Renal failure, peripheral artery disease, and chronic lung disease were the comorbidities with the most detrimental effects on revascularization benefits.

Keywords

Clinical practice guidelines recommend routine invasive management and in-hospital revascularization in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). Elderly patients with comorbid illnesses are underrepresented in clinical trials or even excluded.1 Nonetheless, population aging is leading to an inexorable growth in this patient profile, and physicians often face the paradox of applying therapeutic recommendations drawn from studies comprising qualitatively different patients.2

The largest trial published so far targeting elderly patients suggested the benefit of an invasive strategy.3 However, this study involved a highly selected population with a low comorbidity burden. Comorbidity prevalence increases with age and exerts a strong prognostic impact on NSTEACS.4–7 The benefits of revascularization can only be demonstrated by an adequately sized randomized clinical trial designed for patients with comorbidities; no such study has been performed. Nonetheless, information from real-life registries might provide some relevant clues.

The present study comprised a pooled analysis of individual patient data that included elderly patients from 11 Spanish NSTEACS registries. Our aim was to evaluate the interaction between the effects of revascularization on 1-year mortality and the comorbidity burden. The influence of each individual comorbidity was analyzed, as well as that of the total comorbidity burden.

METHODSStudy populationThis retrospective study comprised 11 cohorts from Spanish NSTEACS registries. Our selection criteria required the registries to collect a minimum set of baseline characteristics during hospital admission and to follow the patients to determine 1-year all-cause mortality. Only patients aged 70 years or older were considered. Registry investigators provided individual patient data to form a pooled patient database. A total of 7211 patients were included. The hospitals participating in the study and their cohorts are shown in .8–17 The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital. Information on the participating cohorts has been published in greater detail.8–17

Patients were managed according to the standard practice in each hospital. Decisions regarding invasive management and revascularization during the index hospitalization were at the discretion of the attending physician. The variables collected are listed in table 1. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score for 6-month mortality was calculated. Six comorbidities identified as independent mortality predictors in a previous study5 were recorded: diabetes, peripheral artery disease, prior stroke, renal function, hemoglobin levels, and chronic pulmonary disease. Renal failure was defined as a glomerular filtration rate<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and anemia as hemoglobin <11g/dL. This hemoglobin cutoff was chosen because it was the most discriminative in previous studies.5,18 Comorbidity burden was defined as the number of comorbidities present.

Characteristics of the patient population

| All patients(n=7211) | Nonrevascularized(n=2872) | Revascularized(n=4339) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 79±6 | 80±6 | 78±5 | .0001 |

| Men | 4441 (62%) | 1527 (53%) | 2914 (67%) | .0001 |

| Smokers | 621 (8.6%) | 179 (6.2%) | 442 (10%) | .0001 |

| Hypertension | 5723 (79%) | 2296 (80%) | 3427 (79%) | .32 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 4262 (59%) | 1639 (57%) | 2623 (61%) | .005 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1682 (23%) | 737 (26%) | 945 (22%) | .0001 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 1334 (19%) | 484 (17%) | 850 (20%) | .004 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft | 573 (7.9%) | 300 (10.4%) | 273 (6.3%) | .0001 |

| Prior admission for heart failure | 641 (8.9%) | 362 (12.6%) | 279 (6.4%) | .0001 |

| Admission systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 141±25 | 141±25 | 143±25 | .002 |

| Admission heart rate, bpm | 79±19 | 80±20 | 78±20 | .003 |

| Admission Killip class ≥ 2 | 1889 (26%) | 880 (31%) | 1009 (23%) | .0001 |

| ST-segment deviation | 2638 (37%) | 933 (33%) | 1705 (39%) | .0001 |

| Left bundle branch block or permanent pacemaker | 1147 (16%) | 526 (18%) | 621 (14%) | .001 |

| Troponin elevation | 5319 (74%) | 2157 (75%) | 3162 (73%) | .04 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 54±11 | 54±12 | 55±11 | .54 |

| GRACE score for 6-mo mortality, points | 150±21 | 152±21 | 148±19 | .0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 2874 (40%) | 1152 (40%) | 1722 (40%) | .73 |

| Prior stroke | 831 (12%) | 368 (13%) | 463 (11%) | .006 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1006 (14%) | 427 (15%) | 579 (13%) | .07 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1161 (16%) | 468 (16%) | 693 (16%) | .72 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/d) | 1025 (14%) | 486 (17) | 539 (12) | .0001 |

| Renal failure (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 3070 (43%) | 1431 (50%) | 1639 (38%) | .0001 |

| Treatment at discharge* | ||||

| Aspirin | 6194 (91%) | 2183 (82%) | 4011 (96%) | .0001 |

| Clopidogrel | 4341 (64%) | 1071 (40%) | 3270 (79%) | .0001 |

| Ticagrelor | 327 (4.8%) | 37 (1.4%) | 290 (7.0%) | .0001 |

| Prasugrel | 38 (0.6%) | 4 (0.1%) | 34 (0.8%) | .0001 |

| Statins | 5938 (87%) | 2136 (80%) | 3802 (91%) | .0001 |

| Outcome | ||||

| 1-y mortality | 1090 (15%) | 597 (21%) | 493 (11%) | .0001 |

The main end point was all-cause mortality at 1 year. All patients except 190 (3.1%) completed follow-up. The median duration of follow-up in patients lost to follow-up was 60 days (interquartile range, 7-226 days). Information on mortality was collected from the hospital files or the regional mortality registry.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed are mean±standard deviation, whereas categorical variables are expressed as absolute values (percentages). Baseline characteristics according to status defined by revascularization at admission were compared by an independent sample t test or chi-square test, as appropriate.

First, we sought to determine a base model for mortality using Cox regression analysis. Hospital centers were included as strata to allow each center to have its own baseline hazard. Risk estimates were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). To select the best base model, we performed a backward elimination procedure, in which the initial (or saturated) model included the characteristics presented in table 1, except for the 6 above-mentioned comorbidities. This procedure included backward elimination while simultaneously testing each continuous variable for departure from linearity. When necessary, variables were transformed with the appropriate fractional polynomials. Proportionality assumptions for the hazard function over time were tested by means of Schoenfeld residuals. The discriminative ability of the multivariate model was evaluated with Harrell's C-statistics. The base multivariate model for mortality included (all main effects) age (years), sex, prior history of acute myocardial infarction, prior history of admission for heart failure, admission heart rate (bpm), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), Killip class ≥ II, ST-segment deviation, elevated troponin, and left ventricular ejection fraction. Over this base model, we tested if the 6 comorbidities possessed predictive ability for mortality (as the main effect) and if their inclusion modified the effect of the revascularization procedure. Within the Cox model, the effects of comorbidities were based on a) a significant omnibus P value of the interaction with revascularization, and b) the prognostic value added by significant ΔC-statistics between the full model (which included the interaction) and the base model.

Second, to increase the robustness of the analysis, we determined whether the differences in mortality rates corroborated the results expressed as HRs. Accordingly, using an additive interaction, we explored the differences in mortality rates (as number of events per person-year) along the continuum of the number of comorbidities. Incidence rate analysis was performed with Poisson regression, with follow-up time included as an offset and the model adjusted for the clustering effect of centers. These absolute measure estimates complement the relative measures provided by the HRs of the Cox models. Because invasive coronary angiography is carried out prior to revascularization, we also performed a sensitivity analysis using invasive management as an exposure variable instead of revascularization.

In addition, a logit regression model was used to estimate the propensity score for revascularization at admission as an ancillary analysis. The propensity score was then stratified into an optimal number of quantiles (16 here), where optimal means that no significant differences were found between treatment groups within any quantile of the propensity score. To use the strata-generated data in any subsequent analysis, an inverse probability of treatment weight was estimated. The variables included in the creation of the propensity score are shown in .

Missing values were imputed by means of 5 imputations using the multiple imputation by chained equations procedure. The estimates of the models using a nonimputed data set were also calculated ().

Stata 15.1 (Stata Statistical Software, Release 15 [2017]; StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, United States) was used for the main analyses. Multiple imputation was performed with the ICE package in Stata.

RESULTSBaseline characteristicsPatient characteristics are shown in table 1. The mean age was 79±6 years and 62% were men. The mean GRACE score for 6-month mortality was 150±28 points. Adherence to guideline-recommended treatments was generally high (table 1). Invasive coronary angiography was performed in 6032 patients (84%) during the hospital admission; 434 (7.2%) had left main disease and 1990 (33%) had 3-vessel disease. A total of 4339 patients (60% of total) were revascularized using percutaneous coronary intervention (n=3848, 53%) or coronary surgery (n=491, 7%).

Baseline differences between revascularized and nonrevascularized patients are shown in table 1. The GRACE score was slightly higher in nonrevascularized patients (152±21 vs 148±21 points, P=.0001). The frequencies of prior stroke, anemia, and renal failure were higher in the nonrevascularized subgroup, whereas there were no differences in diabetes, peripheral artery disease, or chronic pulmonary disease.

Prognostic impact of comorbidities and revascularizationIn total, 1090 patients (15%) had died at 1 year. Differences were found among centers regarding in-hospital revascularization (P=.001; range, 45%-71%) and 1-year mortality (P=.001; range, 11%-19%). Therefore, we mitigated the potential for bias by stratifying all Cox regression analyses by hospital center. Estimates from the Cox regression models are presented in table 2. Except for prior stroke, which showed a nonsignificant trend, each comorbidity was significantly associated with mortality. The ΔC-statistics between the model with the 6 comorbidities and the base model was 0.0187 (95%CI, 0.0120-0.0254; Δs significant at P <.05). As expected, the discrimination accuracy of the GRACE score (C-statistics, 0.734) was inferior to that of the base model (C-statistics, 0.760; P <.05).

Predictive models for 1-year mortality without comorbidities (base model) and with comorbidities (full model)

| Base model | Comorbidities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age (per 5 y) | 1.30 (1.23-1.37) | .0001 | 1.28 (1.21-1.36) | .0001 |

| Male sex | 1.30 (1.14-1.48) | .0001 | 1.24 (1.08-1.42) | .002 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.13 (0.90-1.30) | .098 | 1.05 (0.90-1.21) | .526 |

| Prior admission for heart failure | 1.43 (1.22-1.68) | .0001 | 1.22 (1.03-1.43) | .018 |

| Admission systolic blood pressure (per 10 mmHg) | 0.91 (0.88-0.93) | .0001 | 0.91 (0.89-0.93) | .0001 |

| Admission heart rate (per 20 bpm) | 1.10 (1.03-1.17) | .003 | 1.07 (1.00-1.14) | .038 |

| Admission Killip class ≥ 2 | 2.79 (2.43-3.21) | .0001 | 2.43 (2.11-2.79) | .0001 |

| ST-segment deviation | 1.58 (1.39-1.80) | .0001 | 1.52 (1.34-1.73) | .0001 |

| Troponin elevation | 1.40 (1.13-1.74) | .002 | 1.35 (1.08-1.67) | .007 |

| LVEF ≤ 40% | Reference | Reference | ||

| LVEF 41%-49% | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) | .117 | 0.81 (0.65-1.01) | .065 |

| LVEF ≥ 50% | 0.76 (0.65-0.88) | .0001 | 0.75 (0.65-0.87) | .0001 |

| Revascularization | 0.58 (0.51-0.66) | .0001 | 0.61 (0.53-0.69) | .0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.15 (1.01-1.30) | .032 | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.29 (1.12-1.49) | .001 | ||

| Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.75 (1.53-2.00) | .0001 | ||

| Hemoglobin <11 g/dL | 1.30 (1.13-1.50) | .0001 | ||

| Prior stroke | 1.13 (0.96-1.34) | .129 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | 1.41 (1.21-1.63) | .0001 | ||

| C-statistics | 0.760 | 0.778 | ||

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Absolute mortality was higher in nonrevascularized patients than in revascularized patients (n=597 vs n=493, 21% vs 11%, respectively; P=.0001). As shown in table 2, revascularization was significantly associated with lower mortality; the magnitude of the association was not changed by the addition of comorbidities to the model (HR, 0.61; 95%CI, 0.53-0.69; P=.0001).

Interaction between the effects of revascularization and individual comorbiditiesThe effects of revascularization differed according to individual comorbidity (figure 1). Indeed, the association between revascularization and mortality was only borderline significant in patients with peripheral artery disease and chronic pulmonary disease (P for interaction=.007 and .03, respectively). On the other hand, although the effect of revascularization was significant in patients both with and without renal failure, its magnitude was greater in patients with normal renal function (P for interaction=.004). In contrast, the potential benefit of revascularization was not modified by diabetes, anemia, or previous stroke.

All-cause mortality. Effects of revascularization according to comorbidity. Values express hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. N=7211. All models were adjusted for age, sex, prior myocardial infarction, prior admission for heart failure, admission systolic blood pressure, heart rate, Killip class, ST-segment deviation, troponin elevation, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

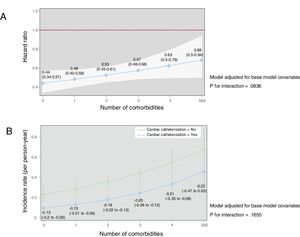

Patient distribution according to the number of comorbidities was as follows: 0 (n=1891; 26.2%), 1 (n=2413; 33.5%), 2 (n=1638; 22.7%), 3 (n 879; 12.2%), 4 (n=314; 4.4%), 5 (n=71; 1.0%), and 6 (n=5; 0.1%). For further analysis, the subgroups with 5 and 6 comorbidities were collapsed into a single subgroup (n=76; 1.1%). The number of comorbidities was associated with mortality (per comorbidity: HR, 1.34; 95%CI, 1.27-1.41; P=.0001). The estimates of the models were similar using the nonimputed data set (). There was a significant interaction between the effects of revascularization and the number of comorbidities in the multiplicative and additive scales. Figure 2A and table 3 show the effect of revascularization along the continuum of the comorbidity burden in multiplicative analysis (omnibus P=.016). The association between revascularization and mortality progressively decreased across the number of comorbidities: from a HR of 0.48 (95%CI, 0.39-0.61) with 0 comorbidities to 0.83 (95%CI, 0.62-1.12) with ≥ 5 comorbidities. The results were similar using the propensity score model (figure 2B). In the additive analysis (omnibus P=.007) and in terms of absolute risk, differences in 1-year mortality rates between revascularized and nonrevascularized patients were significantly favorable to revascularization across all levels of comorbidity, except in the subgroup with very high comorbidity burden (≥ 5 comorbidities) (table 3). The same was observed in the nonimputed data set analysis ().

Effects of revascularization on all-cause mortality according to the number of comorbidities. The solid blue line represents the hazard ratio while the white shadow represents the 95% confidence interval. Values express hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. A: the model was adjusted for age, sex, prior myocardial infarction, prior admission for heart failure, admission systolic blood pressure, heart rate, Killip class, ST-segment deviation, troponin elevation, and left ventricular ejection fraction. B: propensity score model.

Effects of revascularization on 1-year mortality according to number of comorbidities

| Number of comorbidities | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P | Difference in mortality rate (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=1891; 26.2%) | 0.48 (0.39 to 0.61) | .0001 | −0.09 (−0.13 to−0.06) | .0001 |

| 1 (n=2413; 33.5%) | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.63) | .0001 | −0.10 (−0.14 to−0.07) | .0001 |

| 2 (n=1638; 22.7%) | 0.60 (0.53 to 0.68) | .0001 | −0.11 (−0.16 to−0.07) | .0001 |

| 3 (n=879; 12.2%) | 0.67 (0.57 to 0.78) | .0001 | −0.12 (−0.18 to−0.05) | .0001 |

| 4 (n=314; 4.4%) | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.93) | .009 | −0.11 (−0.21 to−0.01) | .039 |

| 5 or 6 (n=76; 1.05%) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.12) | .226 | −0.09 (−0.28 to 0.084) | .40 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

In sensitivity analysis using invasive management as the exposure variable, the results were quite similar (figure 3). Indeed, the association between the performance of cardiac catheterization and mortality decreased from a HR of 0.44 (95%CI, 0.34-0.57) with 0 comorbidities to 0.68 (95%CI, 0.50-0.90) with ≥ 5 comorbidities.

Effects of invasive management on all-cause mortality according to the number of comorbidities. Models were adjusted for age, sex, prior myocardial infarction, prior admission for heart failure, admission systolic blood pressure, heart rate, Killip class, ST-segment deviation, troponin elevation, and left ventricular ejection fraction. A: the solid blue line represents the hazard ratio while the white shadow represents the 95% confidence interval. B: difference in mortality rates (number of deaths per person-year with 95% confidence intervals) according to whether patients underwent invasive management.

The main findings of the present study in elderly patients hospitalized for NSTEACS were as follows: a) comorbidities exerted a strong influence on 1-year mortality; b) in-hospital revascularization improved 1-year mortality on top of comorbidities; however, the revascularization benefit was progressively reduced with an increased comorbidity burden; and c) renal failure, peripheral artery disease, and chronic pulmonary disease were the most detrimental comorbidities to the potential benefit of in-hospital revascularization.

Comorbidities in elderly patients with NSTEACSComorbidities are highly prevalent in elderly patients with NSTEACS and portend a worse outcome. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, which comprises 19 elements, is the most common metric for comorbidity assessment, although the 6 comorbidities that best capture prognostic impact in patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes are renal failure, anemia, chronic pulmonary disease, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes.5,19 Several studies have demonstrated the separate prognostic roles of each of these comorbidities in acute coronary syndrome.18,20–23 Peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and NSTEACS are concordant cardiovascular conditions that reflect a broad systemic extension of the atherosclerotic disease. Likewise, chronic renal failure and diabetes are directly involved in accelerating the atherosclerotic process. Anemia and chronic pulmonary disease are discordant conditions that demand integrated multidisciplinary care that cannot always be properly coordinated. In our study, peripheral artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and renal failure were the comorbidities with the most detrimental effects on the benefits of revascularization. Additionally, we observed an additive effect of comorbidities: the higher the number, the worse the outcome.

Revascularization in elderly patients with NSTEACS and comorbiditiesAmong the guideline recommendations for NSTEACS, in-hospital coronary revascularization provides the greatest prognostic benefit, particularly in high-risk patients.16,24 Indeed, a recent registry showed a significant inverse association between in-hospital coronary revascularization and 2-year mortality.24 A key question is whether a high comorbidity burden precludes elderly patients from the benefits of revascularization. The After-Eighty trial supported a routine invasive strategy in patients older than 80 years with NSTEACS.3 A meta-analysis that included a subgroup of patients older than 75 years from randomized clinical trials also favored invasive management.25 However, patients with comorbidities are underrepresented in randomized clinical trials. A large registry of percutaneous coronary intervention showed that comorbidities are associated with higher rates of in-hospital mortality.26 Accordingly, the best management of severely ill elderly patients with NSTEACS remains controversial.27 In a small-sized trial including elderly patients with comorbidities, routine invasive management was associated with a nonsignificant tendency for a better outcome.28

Our analysis included a large number of elderly patients with NSTEACS and suggests an association between in-hospital revascularization and lower 1-year mortality, as well as the attenuation of this association with an increasing comorbidity burden. Diagnostic coronary angiography is indicated as a previous step to revascularization, which would be a source of bias for the interpretation of prognosis in nonrevascularized patients.29 Indeed, after coronary angiography, some patients might not have been revascularized due to highly complex anatomy or excessive risk. This fact by itself might worsen the prognosis of the nonrevascularized group. However, the sensitivity analysis performed with patients who did not undergo diagnostic angiography as the comparator group instead of nonrevascularized patients also showed an association between invasive management and lower 1-year mortality, which decreased with an increase in the comorbidity burden.

LimitationsFirst, the most important limitation of this study is that we did not evaluate frailty nor sarcopenia or albumin concentrations. Frailty and comorbidities have complementary and additional prognostic value after acute coronary syndrome.30 Although our study only analyzed comorbidity status and not the entire spectrum of geriatric conditions, the demonstration that the higher the comorbidity burden, the lower the benefit of revascularization for 1-year mortality could provide useful information for decision-making in elderly patients hospitalized for NSTEACS. Further studies will clarify the role of revascularization in frail patients hospitalized with NSTEACS.31 Second, the study has the selection biases inherent to all observational registries. There were baseline differences between the revascularized and nonrevascularized patients, and lower-risk patients underwent more revascularization procedures. To offset this bias, we conducted an exhaustive statistical analysis and fully adjusted the predictive models. Third, there was some heterogeneity among the included registries in terms of patient characteristics and management, definitions of variables, and quality of follow-up. Although we mitigated the potential for bias by stratifying all analyses by hospital center, this potential source of bias limits the external validity of the results. Fourth, some characteristics not collected in the database might also play a role in the worse prognosis of the nonrevascularized patients.

CONCLUSIONSOur observations suggest that revascularization should not be ruled out in most elderly patients with comorbidities and NSTEACS. However, the comorbidity burden might offset the potential benefits of revascularization. Therefore, the decision must be cautiously meditated in patients with a high comorbidity burden. Peripheral artery disease, chronic lung disease, and renal failure were the comorbidities found to interfere most with the effects of revascularization.

FUNDINGThis work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the Carlos III Health Institute: CIBER-CV 16/11/00420, Madrid, Spain.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. Núñez has received personal fees from Novartis, Vitor Pharma, and Boehringer Ingelheim and grant support from Astra Zeneca and Vitor Pharma. J.A. Barrabés has received fees for educational activities from AstraZeneca and for consultancy from Bayer. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose. E. Abu-Assi is associate editor of Revista Española de Cardiología.

- -

Clinical practice guidelines, based on clinical trials, recommend routine invasive management and in-hospital revascularization in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS).

- -

Elderly patients with comorbid illnesses are underrepresented in or excluded from clinical trials on NSTEACS.

- -

The optimal management of elderly patients with comorbidities and NSTEACS remains controversial.

- -

Comorbidity burden might offset the potential benefits of revascularization.

- -

There is a progressive inverse relationship between revascularization benefits and comorbidity burden.

- -

Renal failure, peripheral artery disease, and chronic lung disease are the most detrimental comorbidities to the protective effect of revascularization in elderly patients with NSTEACS.

- -

Revascularization should not be ruled out in most elderly patients with comorbidities and NSTEACS. However, the decision must be cautiously meditated in patients with a high comorbidity burden.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.06.015