Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) is a serious disorder, which can occasionally be difficult to diagnose. Symptoms suggestive of PTE include the sudden onset of dyspnea, chest pain and hypotension in patients without pulmonary congestion, or a history of prolonged bedrest, chronic venous insufficiency, neoplasms, pregnancy, or the use of oral contraceptive agents.1-3 Diagnosis of PTE can be confirmed by perfusion ventilation scanning, or, more especially, by high resolution computerized tomography (CT).4,5 Pulmonary thromboembolism may be accompanied by nonspecific changes on the electrocardiogram (ECG), such as right bundle branch block (RBBB), secondary to a sudden overload of the right chambers.6-9 To date, however, no description exists of a patient with PTE accompanied by complete atrioventricular block (CAVB). We present a patient in whom PTE was associated with CAVB.

CLINICAL CASE

The patient was a 73-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer, diagnosed 10 years previously. At that time the ECG showed left bundle branch block (LBBB) and the echocardiogram showed conserved ventricular function (ejection fraction: 56%). In January 2002 she was diagnosed with bone metastasis, for which she received several cycles of chemotherapy plus radiotherapy of the metastasis, achieving clinical stability. One year later an isotopic ventriculography showed worsening of the ejection fraction (46%), which was attributed to chemotherapy.

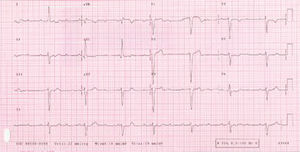

The patient was admitted to our center in December 2003 following sudden onset of dyspnea and presyncope, and CAVB was documented (Figure 1). She was not taking any negative chronotropic drugs and no electrolyte imbalance was detected. After placement of a temporary pacing wire the patients' clinical condition failed to improve and she required high concentrations of oxygen. Approximately 8 hours after admission she recovered sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 90 beats per minute, though she remained tachypneic. A chest radiograph revealed no signs of heart failure and the echocardiogram showed no differences compared to the previous recordings. Given the patient's history, a possible PTE was suspected. A positive D dimer test (>4000 ng/dL) and a helicoidal CT confirmed the presence of bilateral PTE. Treatment with enoxaparin was started, and within 48 hours the patient improved clinically and oximetrically. Five days after admission, an electrophysiological study was undertaken to determine whether placement of a definitive pacemaker was necessary. This study showed normal conduction parameters, with an HV interval of 50 ms (Figure 2), which lengthened to 66 ms with procainamide. Retrograde conduction was also preserved. Because of these findings, implantation of a pacemaker was not considered necessary and the presence of the CAVB was attributed to the PTE. The patient's course was satisfactory and she was discharged ten days after admission and given dicumarinic anticoagulant therapy.

Figure 1. Third-degree atrioventricular block with junctional escape rhythm and a wide QRS secondary to left bundle branch block.

Figure 2. Normal basal conduction parameters with an HV interval of 50 ms and an AH interval of 68 ms.

DISCUSSION

PTE is a disorder that can involve serious hemodynamic consequences, which may even result in death.10 The changes are due to a sudden decrease in the preloading of the left ventricle resulting from obstruction of the pulmonary artery or its branches, with the subsequent reduction in cardiac output.1 PTE may be associated with nonspecific disorders on the ECG, such as RBBB or ST-T segment alterations due, among other causes, to pulmonary hypertension.6,7,9 The mechanism of these disorders remains unknown; the RBBB is attributed to a purely mechanical phenomenon arising from sudden compression of the interventricular septum secondary to the acute overload caused by the PTE.8

We are unaware of any previous reports of a patient with CAVB associated with PTE. We suggest that in this patient who had established LBBB, the onset of RBBB secondary to the PTE may have caused the CAVB. However, against this hypothesis is the report by Athar et al11 of a patient with known LBBB in whom PTE induced transient normalization of conduction on the ECG, with bradycardia and signs of right overload, but no CAVB. The LBBB in this patient may have been dependent on the rate, and the bradycardia normalized the conduction. In our patient, uncertainty exists whether the CAVB and the PTE were a casual association or whether the CAVB was a consequence of the PTE. The presence of normal conduction parameters, even with procainamide, confirmed the indemnity of the conduction system.

Another possible explanation is that the CAVB was secondary to ischemia induced by the hemodynamic situation of shock due to the PTE.12 However, although we have no coronary angiography studies to rule out the presence of lesions which could possibly cause a CAVB, no electrical changes suggestive of ischemia were noted, nor was there any rise in enzymes, and at no time was the patient in a state of shock (her minimum blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg). Nevertheless, the echocardiogram failed to provide a definitive diagnosis, probably because it was undertaken when the patient had already recovered normal rhythm, which suggests recanalization of the pulmonary artery by spontaneous thrombolysis. Thus, in the patient reported here, we believe that the PTE could have caused a RBBB, which in the presence of a LBBB led to the CAVB.

Correspondence: Dr. J. Martí Almor.

Passeig Marítim, 25-29. 08003 Barcelona. España.

E-mail: jmarti@imas.imim.es