The role of emergency coronary angiography (CAG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in patients without ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains unclear. We aimed to assess whether emergency CAG and PCI would improve survival with good neurological outcome in this population.

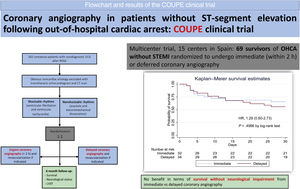

MethodsIn this multicenter, randomized, open-label, investigator-initiated clinical trial, we randomly assigned 69 survivors of OHCA without STEMI to undergo immediate CAG or deferred CAG. The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of in-hospital survival free of severe dependence. The safety endpoint was a composite of major adverse cardiac events including death, reinfarction, bleeding, and ventricular arrhythmias.

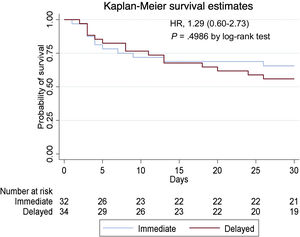

ResultsA total of 66 patients were included in the primary analysis (95.7%). In-hospital survival was 62.5% in the immediate CAG group and 58.8% in the delayed CAG group (HR, 0.96; 95%CI, 0.45-2.09; P=.93). In-hospital survival free of severe dependence was 59.4% in the immediate CAG group and 52.9% in the delayed CAG group (HR, 1.29; 95%CI, 0.60-2.73; P=.4986). No differences were found in the secondary endpoints except for the incidence of acute kidney failure, which was more frequent in the immediate CAG group (15.6% vs 0%, P=.002) and infections, which were higher in the delayed CAG group (46.9% vs 73.5%, P=.003).

ConclusionsIn this underpowered randomized trial involving patients resuscitated after OHCA without STEMI, immediate CAG provided no benefit in terms of survival without neurological impairment compared with delayed CAG.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02641626

Keywords

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major public health problem that accounts for most deaths in coronary artery disease. Despite advances in the field of resuscitation and intensive care management, the outcome of these patients remains poor and over 70% of them die or survive with severe neurological impairment.1

It has been reported that implementation of a standardized treatment protocol for postresuscitation care after OHCA, including therapeutic hypothermia, urgent coronary intervention in suitable patients and optimization of intensive care treatment improved survival compared with controls before the implementation of this protocol.2

Evidence that coronary angiography (CAG) may reduce mortality in OHCA patients was obtained from several observational studies, most of them including patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).3–6 Based on these studies, guidelines recommend a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) strategy in patients with resuscitated cardiac arrest and an electrocardiogram consistent with STEMI (class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).7–10 Previous guidelines stated that an emergent CAG (and PCI if indicated) should be considered in patients with OHCA without diagnostic ST-segment elevation but with a high suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischemia (class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).7,8,11 However, recently, 2 randomized controlled clinical trials have been published aiming to determine the effectiveness of an immediate CAG in reducing mortality in OHCA patients without STEMI. Both studies concluded that an immediate CAG provided no survival benefit over a delayed strategy. Recent guidelines12–14 state that a delayed (within the first 24hours) as opposed to immediate CAG should be considered in hemodynamically stable OHCA patients without ST elevation based on the results of the Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial.15 However, in this trial, a coronary angiogram in the delayed CAG group was performed within a median of 5 days. Hence, there is still uncertainty about the ideal time to perform angiography in this group of patients.

The coronary angiography in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients without ST-segment elevation (COUPE) trial is a randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of an emergency CAG and angioplasty, if necessary, in OHCA survivors who, after restoration of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), do not fulfil the criteria for STEMI and do not have an obvious noncoronary cause of the arrest.

METHODSStudy design and oversightThe COUPE trial is a prospective, multicenter, randomized open-label, investigator-initiated clinical trial comparing the efficacy of emergency vs deferred CAG in survivors of an OHCA without STEMI. The trial design has been published previously.16 The protocol was designed by the authors and approved by the ethics committee at each participating site.

All the investigators at the trial sites vouch for the completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. An independent statistician ensured the accuracy of the data analysis.

Centers and patientsA total of 15 tertiary centers in Spain participated in the study. All these hospitals are high volume PCI centers with 24/7 PCI service and with experience in treating OHCA patients in intensive cardiac care units. All of them perform therapeutic hypothermia or targeted temperature management as part of postresuscitation care.

Patients were eligible if they had ROSC within 60minutes, remained in coma, and had an electrocardiogram without STEMI or left bundle branch block. Both shockable and nonshockable rhythms were included in the study. Obvious noncoronary etiology of the cardiac arrest was ruled out prior to randomization, for instance, drug overdose, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, acute stroke, or intracranial bleeding. Cranial computed tomography and echocardiography were performed for this purpose. Further inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in table 1 of the supplementary data and table 2 of the supplementary data. Written informed consent was obtained from all patientś next of kin. All patients who recovered consciousness were informed about their study participation and signed a deferred consent form for use of the study data at that time. Informed consent could be withdrawn at any time and for any reason.

Randomization and treatmentEligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to undergo either immediate CAG (and PCI if needed) or delayed CAG (and PCI if needed). Figure 1 of the supplementary data shows the COUPE trial flowchart. Study group assignment was performed by block randomization, in blocks of 6 patients. Randomization was stratified according to the initial rhythm of the cardiac arrest (shockable and nonshockable).

In the immediate CAG group, coronary angiography was performed as soon as possible within 2hours after hospital admission and randomization. In the delayed CAG group, coronary angiography was performed after neurological recovery, when the patient was extubated, in general before being discharged from the intensive cardiac care unit.

Both groups received routine care in the intensive cardiac care unit, including therapeutic hypothermia with a target temperature of 33°C for 24hours. Supporting treatment, such as mechanical ventilation, sedation, and any other medical therapy, was delivered according to standard practice and at the discretion of the treating physicians. Blood samples for troponin determination were obtained at admission and at 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72hours after admission. Type of troponin (T, I and ultra-sensitive depending on the hospital's laboratory kits) was recorded. Hemogram and biochemistry including magnesium, lactate, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and neuron-specific enolase, were obtained at admission and 24, 48 and 72hours after admission. An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram were performed at admission, when the patient reached target temperature and after rewarming.

CAG was performed according to the local protocol. The access site, the anticoagulant therapy and the revascularization strategy were left to the discretion of the treating physicians. In cases of multivessel disease, the strategy was discussed in the local heart team. If coronary artery bypass surgery was the treatment of choice for a patient in the immediate CAG group, this procedure was postponed until after neurological recovery. If patients initially randomized to the deferred CAG strategy showed signs of refractory cardiogenic shock or recurrent arrhythmias during their hospitalization, they underwent emergency CAG.

Follow-up and endpointsThe estimated duration was 3 years, with a target follow-up of 6 months. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, recruitment was slower than expected. Survival, neurological status and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were evaluated on clinical follow-up.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of in-hospital survival free of severe dependence, assessed with the Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) scale,17 good prognosis being represented by categories 1 and 2. The primary safety endpoint was in-hospital major adverse cardiac events including death, reinfarction, bleeding, and ventricular arrhythmias. Secondary endpoints included in-hospital and 6-month survival, in-hospital and 6-month neurological prognosis assessed by the CPC scale, in-hospital and 6-month LVEF, infarction size measured with cardiac markers, vascular complications, bleeding, ventricular arrhythmias, acute renal failure, stent thrombosis, infections, length of intubation, and length of stay (table 3 of the supplementary data and table 4 of the supplementary data).

Statistical analysisA previous meta-analysis of 55 nonrandomized studies showed improved survival for immediate angiography vs conventional treatment: 58.8% vs 30.9% with an odds ratio of 2.77 (95%CI, 2.06-3.72).18 Based on previous studies, we calculated a sample size of 92 patients would be required to detect an absolute increase of 28% in the survival rate of the study group (immediate CAG) with 80% statistical power. Considering a 10% patient loss during the follow-up, a sample size of 102 (51 patients in each group) would be needed to test the superiority hypothesis.

Unfortunately, sample size was smaller than expected due to the coronavirus pandemic, which made recruitment tremendously challenging. For this reason, the study was not sufficiently powered for the primary endpoint and results should be considered as exploratory.

Endpoints were analyzed for all recruited patients in an intention to treat analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by an independent investigator, blinded to the study group assignment.

Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range and comparisons between groups were performed with the Hodges-Lehmann approach for independent groups. Categorical variables are expressed as count and percentages and groups were compared with the chi-square test. Survival analysis was performed with the Kaplan-Meier analysis and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test. For the primary endpoint, survival between groups was compared by using a univariate Cox proportional risk analysis. Regarding MACEs, differences between groups were assessed with the chi-square test, and the effect size was expressed with the risk ratio and the risk difference. Statistical significance was considered as a P value <.05. All data management and subsequent analysis was performed with STATA 17 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

RESULTSPatientsFrom February 2016 through December 2020, a total of 69 survivors of OHCA without STEMI were enrolled at 15 centers in Spain. Three of these patients were excluded from the analysis because they did not fully complete the randomization process. Finally, 66 patients were randomly assigned to the immediate CAG (32 patients) or the delayed CAG (34 patients) group. The baseline characteristics of the patients were balanced in the 2 groups (table 1). Median age was 63 (interquartile range [IQR], [56-72]) years and 22.7% of the patients were women. Ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia was the initial rhythm in 81.8%, with the remaining 18.2% having a nonshockable rhythm. Median time from arrest to ROSC was 21.5minutes.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Immediate angiography(n=32) | Delayed angiography(n=34) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 66.5 [60-73.5] | 60.5 [55-71] | .086 |

| Male sex | 26 (81.3) | 25 (73.6) | |

| Body mass index* | 26.8 [25.5-29] | 26 [24.5-8.7] | .139 |

| Medical condition of risk | |||

| Diabetes | 5 (15.6) | 10 (30.3) | .1603 |

| Hypertension | 22 (68.8) | 22 (66.7) | .8575 |

| Dyslipidemia | 21 (65.6) | 15 (46.9) | .1306 |

| Current smoker | 7 (21.9) | 10 (29.4) | .527 |

| Alcohol abuse | 4 (12.5) | 7 (20.6) | .3782 |

| Drug abuse | 2 (6.3) | 3 (8.8) | .664 |

| Coronary artery disease | 7 (21.9) | 8 (23.5) | .928 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4 (12.5) | 4 (11.8) | .999 |

| Previously on anticoagulation | 7 (21.9) | 5 (14.7) | .578 |

| Shockable first monitored rhythm | 27/32 (84.4) | 27/34 (79.4) | .5986 |

| Before hospital admission | |||

| Time from arrest to return of spontaneous circulation - min | 20 [15-25] | 23 [15-32] | .445 |

| Blood pH | 7.22 [7.1-7.3] | 7.17 [7.0-7.3] | .453 |

| Lactate- mmol/L | 6.28 [4.17-9.80] | 5.90 [2.5-13.10] | .611 |

| After hospital admission | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 126 [110-140] | 120 [100-140] | .250 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 47 [40-60] | 49 [40-60] | .034 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Oxygen saturation | 99 [97-100] | 99 [98-100] | .821 |

| Blood pH | 7.32 [7.27-7.35] | 7.31 [7.22-7.39] | .818 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 3.1 [1.62-6.10] | 3.1 [1.60-6.60] | .611 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 21 [18.8- 23.3] | 23.1 [21- 25] | .094 |

Details about procedures and treatments are provided in table 2. Coronary angiography was performed in all of the patients in the immediate CAG group and in 20 patients (58.9%) in the delayed CAG group. The median time from cardiac arrest to CAG was 3.8 [IQR, 2.9-4.3] hours in the immediate CAG group and 129 (5.4 days) in the delayed CAG group [IQR, 89-187] hours. The prevalence of coronary disease was 53.1% among patients who underwent immediate CAG and 40% among patients in the delayed CAG group. A culprit lession was found in 37.5% of the patients in the immediate CAG group and in 25% of the delayed CAG group. PCI was performed in 31.3% of the patients in the immediate CAG group and in only 10% of the patients in the delayed CAG group, although 15% of patients in the latter group underwent cardiac surgery during hospitalization. All patients received hypothermia with a target temperature of 33°C. The median time from arrest to the initiation of hypothermia was significatively longer in the immediate CAG group (4.4 [IQR, 3-5.4] hours compared with 2.9 in the delayed CAG group [IQR, 1.2 -3.4] hours, P=,006).

Prevalence, characteristics, and treatment of coronary artery disease

| Immediateangiography(n=32) | Delayedangiography(n=34) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary angiography performed | 32 (100) | 20 (58.8) | < .001 |

| Median time from arrest to coronary angiography, h | 2.7 [1.6-3.4] | 129 [87-186] | < .001 |

| Catheterization access | .262 | ||

| Femoral | 5 (15.6) | 1 (5) | |

| Radial | 26 (81.2) | 18 (90) | |

| Braquial | 1 (3.1) | 1 (5) | |

| Severity of coronary artery disease | .073 | ||

| No clinically significant disease | 16 (50) | 12 (60) | |

| One-vessel disease | 10 (31.3) | 2 (10) | |

| Two-vessel disease | 1 (3.1) | 1 (5) | |

| Three-vessel disease | 5 (15.6) | 5 (25) | |

| Acute unstable lesion (culprit lesion)* | 12 (37.5) | 5 (25) | .3499 |

| Revascularization treatment | |||

| PCI | 10 (31.3) | 2 (10) | .0768 |

| CABG | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15) | .0240 |

| Amount of contrast dye, mL | 100 [60-180] | 90.5 [52-140] | .9999 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IQR, interquartile range; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

A total of 66 patients were included in the primary analysis (95.7%). Clinical outcomes are reported in table 3. In-hospital survival free of severe dependence (the primary endpoint) was 59.4% in the immediate angiography group and 52.9% in the delayed angiography group (HR, 1.29; 95%CI, 0.60-2.73; P=.4986) (figure 1). There were also no differences related to in-hospital major adverse cardiac events including death, reinfarction, bleeding and ventricular arrhythmias (primary safety endpoint) between the 2 groups. In-hospital survival was 62.5% in the immediate angiography group and 58.8% in the delayed angiography group (HR, 0.96; 95%CI, 0.45-2.09; P=.9262). No differences were found in any of the other secondary endpoints except for the incidence of acute kidney failure, which was more frequent in the immediate CAG group (15.6% vs 0%, P=.002) and infections, which were higher in the delayed CAG group (46.9% vs 73.5%, P=.003). Additional clinical outcomes are provided in table 3.

Clinical outcomes

| Immediateangiography(n=32) | Delayedangiographya(n=34) | Effect sizeHR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Survival with good neurological outcome (CPC 1 and 2) | 19 (59.4) | 18 (52.9) | HR, 1.29 (0.60-2.73) |

| MACE, No./total | |||

| Death | 12/32 (37.5) | 14/34 (41.2) | RR, 0.91 (0.5-1.66) |

| Myocardial infarction (reinfarction) | 0/32 | 1/34 (2.9) | RD, −0.03 (−0.086 to -0.027) |

| Clinically evident bleeding (BARC ≥ 2) | 3/32 (9.4) | 3/34 (8.8) | RR, 1.062 (0.231-4.88) |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 3/32 (9.4) | 9/34 (26.5) | RR, 0.354 [0.105-1.192] |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| Hospital survival | 20 (62.5) | 20 (58.8) | HR, 1.06 [0.72-1.57] |

| Neurological outcome assessed by the CPC score at dischargeb | |||

| CPC 1 | 17/32 | 16/34 | RR, 1.13 [0.7-1.83] |

| CPC 2 | 2/32 | 2/34 | - |

| CPC 3 | 1/32 | 1/34 | - |

| CPC 4 | 0/32 | 1/34 | - |

| CPC 5 | 12/32 | 14/34 | RR, 0.91 [0.5-1.66] |

| Peak level of neuron-specific enolase | 25.6 [15.8-34] | 20.0 [15,35.8] | MD 2.8 [−5.5-12.1] |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge | 51 [45-60] | 52 [45-60] | MD, 0 [−5-5] |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction at 6 mo | 61.1 [57-62] | 52.3 [45-60] | MD, 5 [0-20] |

| Infarction size (maximum CPK) | 293 [72-689] | 514 [272-1824] | MD, −252 [−628 to −1.35)] |

| Clinically evident hemorrhage: BARC ≥ 2 | 3/32 (9.38%) | 3/34 (8.82%) | RR, 1.062 [0.231-4.88] |

| Acute renal failure | 5/32 (15.6%) | 0/34 (0) | RD, 0.156 [0.03-0.282] |

| Infections/ use of antibiotics | 15/32 (46.9) | 25/34 (73.5) | RR, 0.64 [0.42-0.97] |

| Length of intubation, d | 3 [2-7] | 5 [3-12] | MD, −2 [−4-0] |

| Use of dobutamine | 9 (28.1) | 5 (14.7) | RR, 1.91 (0.72-5.1) |

| Use of noradrenaline | 17 (53.1) | 20 (58.2) | RR, 0.9 (0.59-1.39) |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 15 [6.5-23] | 18 [14-29] | MD, −5 [−12-2] |

| Outcome | |||

| Time from arrest to beginning of hypothermia, h | 4.4 [3-5.4] | 2.9 [1.2-3.4] | MD, 1.5 [0.53-2.37] |

| Time from arrest to target temperature, h | 8.3 [6.3-9.3] | 7 [5-9.9] | MD, 0.93 [−0.83-2.68] |

| Treatment at discharge | |||

| Angiotensin-converter enzyme inhibitors | 13/32 (40.6) | 5/34 (14.7) | RR, 2.76 [1.11-6.87] |

| Beta-blockers | 16/32 (50) | 9/34 (26.5) | RR, 1.89 [0.98-3.65] |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 4/32 (12.5) | 1/34 (2.9) | RR, 4.25 [0.50-36.0] |

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; CPC, Cerebral Performance Category; HR, hazard ratio; RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio; MD, median difference; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

Kaplan-Meier estimates of in-hospital survival free of severe dependence. There were no significant differences in survival without neurological impairment (primary endpoint) among patients resuscitated after OHCA without ST-segment elevation who underwent either immediate coronary angiography or delayed coronary angiography.

In the COUPE trial, we found that among patients resuscitated after OHCA without ST-segment elevation, immediate CAG provided no benefit in terms of survival without neurological impairment compared with delayed CAG. Our findings support the results of 2 previous randomized trials showing no benefit of immediate CAG in this population.15,19 We included patients with both shockable and nonshockable rhythms, as in the TOMAHAWK trial. Other randomized pilot trials20,21 also showed no differences in clinical outcome in patients with OHCA treated with immediate and delayed angiography.

The lack of benefit of immediate CAG may be explained by several findings. Only 50% in the immediate CAG group had significant coronary artery disease (37.5% had an acute unstable lesion considered responsible for triggering cardiac arrest). Even fewer patients in the delayed CAG group (40%) had significant coronary artery disease, and only 25% had a coronary culprit lesion. In this population, with a low rate of coronary artery disease, immediate CAG may increase the risk of complications such as contrast-induced nephropathy or bleeding without any benefit in terms of survival or neurological outcome. Indeed, 15.6% patients in the immediate CAG group developed acute kidney failure compared with none of the patients in the delayed CAG group. In contrast, more patients in the delayed CAG developed infections (75.5% vs 46.9%), possibly due to the longer intubation period (3 days in the immediate CAG group vs 5 days in the delayed CAG group).

Another potential reason for the lack of benefit of early coronary angiography may be that most nonsurvivors died of noncardiovascular complications after the cardiac arrest, mainly of anoxic brain injury (66.7% in the immediate CAG group and 92.9% in the delayed CAG group). This result is consistent with the findings of previously mentioned studies.15,19

All patients in both groups received therapeutic hypothermia with a target temperature of 33°C. This was the usual protocol in most centers but some of them had local protocols with targeted temperatures between 32°C and 36°C, following international guideline recommendations.13,14 Therefore, for this study we set this temperature level to avoid a potential confounding factor of the different targets temperature, which could affect the outcomes of the immediate or delayed CAG. There were no differences in neurologic prognosis between the 2 groups (59.4% in the immediate CAG group had good neurologic outcome and 53% in the delayed CAG group). In the COACT trial, patients assigned to the immediate CAG group reached their target temperature later than those in the delayed angiography group. However, in our trial, there were no significant differences in the time required to achieve target temperature (8.3hours in the immediate CAG group and 7hours in the delayed CAG group). This lack of benefit from urgent CAG was independent of both the temperature level and the rate of achievement of this target temperature. In our study, median time from arrest to ROSC was 21.5minutes, which was longer than in the COACT and in the TOMAHAWK, where this time was 15minutes. Consistent with the above, first lactate was 6.22 mmol/L whereas in the previously mentioned trials it was around 5 mmol/L.

The first link in the chain of survival is early recognition of the cardiac arrest, rapid activation of the emergency medical systems, and prompt initiation of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Recognising cardiac arrest can be challenging. Mandatory nationwide training of schoolchildren has the highest and most important long-term impact for improving bystander CPR rate.22,23 In the long run, this appears to be the most successful way to reach the entire population24. Despite a longer time from arrest to ROSC in our study, survival free of severe dependence was 59.4% in the immediate angiography group and 52.9% in the delayed angiography group. This reasonably good outcome emphasizes the need for OHCA patients to be treated in cardiac arrest centers.25

In an attempt to identify another potential benefit of urgent CAG, we analyzed LVEF, which was one of the prespecified composite secondary endpoints. We found no differences in mean LVEF at discharge but, interestingly, at 6 months of follow-up, mean LVEF was 61.1% in the immediate CAG group compared with 52.3% in the delayed CAG group, almost reaching a significant difference (P=.058). Urgent revascularization may have had a benefit in terms of functional indexes such as LVEF. Another explanation for this improvement in LVEF could be the higher number of patients on angiotensin-converter enzyme inhibitors, beta-blockers and aldosterone antagonists at discharge in the immediate CAG group compared with the delayed CAG group. This finding should be interpreted with caution due to the sample size of the study and needs further investigation in future trials addressing this question.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was smaller than expected for several reasons. Some patients were alone when they had the cardiac arrest and the next of kin could not be identified promptly enough to obtain informed consent. In addition, some physicians thought that performing an emergent CAG was the right therapeutic approach in this subgroup of OHCA patients without ST-segment elevation; hence, they did not enroll any patients. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic delayed recruitment and made it impossible to complete enrollment of the estimated number of patients. As the target sample size was not reached, statistical power was 63.3% and therefore all results should be considered as exploratory. Second, the physicians were not blinded to randomized treatment allocation, but they were not involved in the analysis process. Third, although patients with both shockable and nonshockable rhythms were enrolled, our results do not apply to patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest, ST-segment elevation, left bundle branch block or hemodynamic instability, who were excluded from the trial. Currently, several randomized trials are ongoing and will provide more comprehensive data in selecting the appropriate candidates for immediate CAG.26,27

ConclusionsIn conclusion, in this underpowered randomized trial involving patients resuscitated after OHCA without ST-segment elevation, immediate CAG provided no benefit in terms of survival without neurological impairment compared with delayed CAG (figure 2).

Central illustration. Flow chart and results of the COUPE clinical trial. ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; ROSC, restoration of spontaneous circulation.

The trial was funded by the Carlos III Institute of Health (Project PT13/0002/0003 and PT17/0017/0018) and was cofinanced by the European Fund of Regional Development (FEDER).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSThe corresponding author guarantees that all authors meet each of the following characteristics defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in the criteria for authorship of scientific articles: a) substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and b) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and c) final approval of the version to be published; and d) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTAll authors have no conflicts of interest.

Pablo Salinas, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital Clínico San Carlos (IdISSC), Madrid, Spain.

Luis Nombela-Franco, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital Clínico San Carlos (IdISSC), Madrid, Spain.

Iván Núñez-Gil, Servicio de Cardiología. Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital Clínico San Carlos (IdISSC), Madrid, Spain.

Pedro Cepas Guillén, Instituto Cardiovascular, Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Universidad de Barcelona, Institut D́Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain.

Gonzalo Luis Alonso-Salinas, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

Miriam Juárez, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Iago Sousa, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Carlos Tomás Querol, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida - IRBLL, Lleida, Spain.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2022.05.013