Cost-effectiveness analysis of apixaban (5mg twice daily) vs acenocoumarol (5mg/day) in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in Spain.

MethodsMarkov model covering the patient's entire lifespan with 10 health states. Data on the efficacy and safety of the drugs were provided by the ARISTOTLE trial. Warfarin and acenocoumarol were assumed to have therapeutic equivalence. Perspectives: The Spanish National Health System and society. Information on the cost of the drugs, complications, and the management of the disease was obtained from Spanish sources.

ResultsIn a cohort of 1000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, administration of apixaban rather than acenocoumarol would avoid 18 strokes, 71 hemorrhages (28 intracranial or major), 2 myocardial infarctions, 1 systemic embolism, and 23 related deaths. Apixaban would prolong life (by 0.187 years) and result in more quality-adjusted life years (by 0.194 years) per patient. With apixaban, the incremental costs for the Spanish National Health System and for society would be € 2488 and € 1826 per patient, respectively. Consequently, the costs per life year gained would be € 13 305 and € 9765 and the costs per quality-adjusted life year gained would be € 12 825 and € 9412 for the Spanish National Health System and for society, respectively. The stability of the baseline case was confirmed by sensitivity analyses.

ConclusionsAccording to this analysis, apixaban may be cost-effective in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation compared with acenocoumarol.

Keywords

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a cardiac arrhythmia associated with aging, hypertension, valve diseases, and other heart diseases.1 Nonvalvular AF (NVAF) refers to those cases with a change in rhythm in the absence of rheumatic mitral valve disease, artificial heart valve, or mitral valve repair. Atrial fibrillation is associated with a higher risk of death (twice that of patients without AF), cerebrovascular disease (5-fold higher), and systemic embolism.1

The prevalence of AF is estimated to be 2% in the general Spanish population,1 4.4% in the population aged ≥ 40 years,2 and up to 10.9% and 11.1% in individuals older than 60 years and 79 years, respectively.3,4

The average annual cost of a patient with AF in Spain is estimated to be € 2365; of this sum, € 1008 would correspond to hospital stays, € 723 to surgical interventions, and € 247 lost productivity at work.5 The cost of cardioembolic stroke during the first 38 days after onset has been estimated to be € 13 353.6 The direct nonhealth care costs of stroke, corresponding to informal care of patients with sequels, are calculated to range, depending on severity, from € 252 to € 1031 during the acute phase (2 weeks) and from € 1367 to € 1942 a month during subsequent patient follow-up.7

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) (acenocoumarol and warfarin) are currently the standard treatment for stroke prevention in patients with AF.8 It is estimated that 84% of the AF patients9 in Spain are taking oral anticoagulation therapy, and that 66% are being treated with VKA as monotherapy.10 However, the use of VKA is limited by the risk of bleeding, its narrow therapeutic margin, and the inconvenience to the patient due to the need for monitoring and drug-drug and food-drug interactions. When VKA doses are adjusted, these agents reduce the risk of stroke by 64% vs placebo but they also double the risk of the development of additional and intracranial hemorrhages.11 In Spain, the most widely used agent for oral anticoagulant therapy is acenocoumarol, whereas warfarin is administered in Anglo-Saxon countries.12 According to the available data, the effectiveness of the 2 drugs is assumed to be similar in clinical practice.12,13

According to the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology,14 direct oral anticoagulants, such as apixaban, are preferable to VKA for the treatment of most cases of NVAF, since they are not inferior in terms of efficacy and reduce the number of intracranial hemorrhages.

Apixaban is a new drug for oral administration that exerts a potent, direct and highly selective inhibition of factor Xa to reduce the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin.15 A randomized, double-blind trial16 compared apixaban and warfarin in 18 201 patients with NVAF. The results of that study indicate that apixaban (5mg twice daily) was significantly superior to warfarin in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism, produced fewer episodes of major bleeding, and reduced death from any cause.16

The differences observed between apixaban and acenocoumarol/warfarin may have a health care-related and economic impact. Consequently, we carried out a cost-effectiveness analysis of stroke prevention with apixaban or acenocoumarol in patients with NVAF.

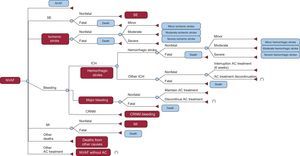

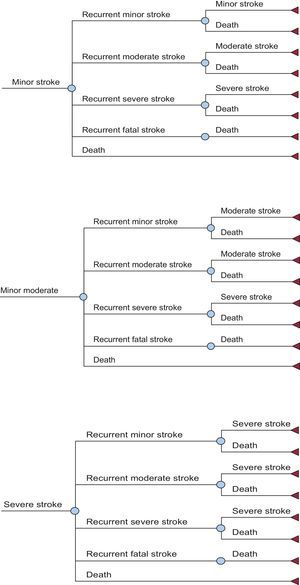

METHODSStudy DesignA cost-effectiveness analysis17 was carried out by adapting the economic model proposed by Dorian et al18 to the Spanish health care setting. This model covers the life-long course (with a life expectancy of 80.4 years for both sexes) of a cohort of 1000 patients with NVAF18,19 whose characteristics were those of the patients in the ARISTOTLE trial.16 It is a Markov model (Figures 1 and 2), with 6-week cycles and 10 major health states. The entire patient cohort was in a state of NVAF and, after each cycle, they remained in NVAF or passed to other states, in accordance with certain transition probabilities.

Markov economic model of stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Course of a patient with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Patients who progress to the state of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation without anticoagulant, return to nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Patients who progress to states of myocardial infarction or systemic embolism can die a posteriori as a consequence of these complications. AC, anticoagulant; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; NVAF, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation; SE, systemic embolism. *Change of treatment to acetylsalicylic acid.

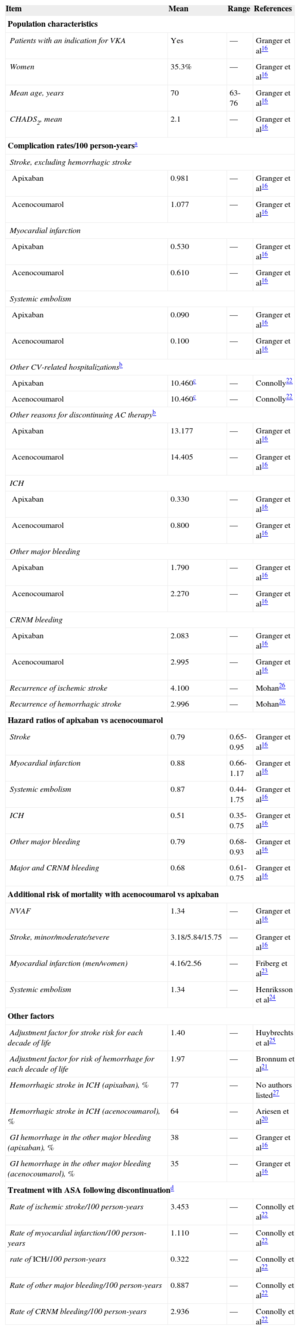

These probabilities of transition from one health state to another (stroke, systemic embolism, bleeding, death) for the drugs under comparison were obtained from the ARISTOTLE clinical trial16 and from other sources when necessary.20–27 According to the model, each patient can experience only 1 complication per cycle and only 1 recurrence of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) is permitted. The simulation of avoided episodes was modeled throughout the patient's lifespan, based on the intention-to-treat analysis in the ARISTOTLE trial. Table 1 shows the rate of complications/100 person-years and the hazard ratio of these complications with acenocoumarol vs apixaban, adjusted according to the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke [doubled]) score, and the international normalized ratio (INR) quality control index according to the time in therapeutic range (TTR).

Population and Risks Considered in the Markov Model

| Item | Mean | Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics | |||

| Patients with an indication for VKA | Yes | — | Granger et al16 |

| Women | 35.3% | — | Granger et al16 |

| Mean age, years | 70 | 63-76 | Granger et al16 |

| CHADS2, mean | 2.1 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Complication rates/100 person-yearsa | |||

| Stroke, excluding hemorrhagic stroke | |||

| Apixaban | 0.981 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 1.077 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Apixaban | 0.530 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 0.610 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Systemic embolism | |||

| Apixaban | 0.090 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 0.100 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Other CV-related hospitalizationsb | |||

| Apixaban | 10.460c | — | Connolly22 |

| Acenocoumarol | 10.460c | — | Connolly22 |

| Other reasons for discontinuing AC therapyb | |||

| Apixaban | 13.177 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 14.405 | — | Granger et al16 |

| ICH | |||

| Apixaban | 0.330 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 0.800 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Other major bleeding | |||

| Apixaban | 1.790 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 2.270 | — | Granger et al16 |

| CRNM bleeding | |||

| Apixaban | 2.083 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Acenocoumarol | 2.995 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Recurrence of ischemic stroke | 4.100 | — | Mohan26 |

| Recurrence of hemorrhagic stroke | 2.996 | — | Mohan26 |

| Hazard ratios of apixaban vs acenocoumarol | |||

| Stroke | 0.79 | 0.65-0.95 | Granger et al16 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.88 | 0.66-1.17 | Granger et al16 |

| Systemic embolism | 0.87 | 0.44-1.75 | Granger et al16 |

| ICH | 0.51 | 0.35-0.75 | Granger et al16 |

| Other major bleeding | 0.79 | 0.68-0.93 | Granger et al16 |

| Major and CRNM bleeding | 0.68 | 0.61-0.75 | Granger et al16 |

| Additional risk of mortality with acenocoumarol vs apixaban | |||

| NVAF | 1.34 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Stroke, minor/moderate/severe | 3.18/5.84/15.75 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Myocardial infarction (men/women) | 4.16/2.56 | — | Friberg et al23 |

| Systemic embolism | 1.34 | — | Henriksson et al24 |

| Other factors | |||

| Adjustment factor for stroke risk for each decade of life | 1.40 | — | Huybrechts et al25 |

| Adjustment factor for risk of hemorrhage for each decade of life | 1.97 | — | Bronnum et al21 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke in ICH (apixaban), % | 77 | — | No authors listed27 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke in ICH (acenocoumarol), % | 64 | — | Ariesen et al20 |

| GI hemorrhage in the other major bleeding (apixaban), % | 38 | — | Granger et al16 |

| GI hemorrhage in the other major bleeding (acenocoumarol), % | 35 | — | Granger et al16 |

| Treatment with ASA following discontinuationd | |||

| Rate of ischemic stroke/100 person-years | 3.453 | — | Connolly et al22 |

| Rate of myocardial infarction/100 person-years | 1.110 | — | Connolly et al22 |

| rate of ICH/100 person-years | 0.322 | — | Connolly et al22 |

| Rate of other major bleeding/100 person-years | 0.887 | — | Connolly et al22 |

| Rate of CRNM bleeding/100 person-years | 2.936 | — | Connolly et al22 |

AC, anticoagulants; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke (double); CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; CV, cardiovascular; GI, gastrointestinal; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; NVAF, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation; VKA, vitamin K antagonists.

Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid after discontinuation of the previous anticoagulation therapy was considered to be due to major bleeding or other causes; it was also considered that the distribution according to severity of the ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke would be the same as that observed with acetylsalicylic acid in the first-line treatment (AVERROES study).

Overall mortality in women and men older and younger than 75 years was obtained by adjusting published Spanish mortality data19 to a Gompertz function, for the purpose of predicting all-cause mortality and excluding that due to stroke and hemorrhage in order to avoid counting them twice. Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid was considered after interruption of previous anticoagulation therapy (acenocoumarol or apixaban) due to major bleeding or other causes.22

For example, with respect to the method of extrapolating the results for acute myocardial infarction from the ARISTOTLE clinical trial16 to the patient's entire lifespan, calculations were based on the risks of having an infarction with apixaban and with warfarin obtained in the clinical trial, with a rate of 100 person-years of 0.53 and 0.61, respectively. These annual risks were transformed into a risk model for a 6-week period (the duration of the cycles of the Markov model). Thus, every 6 weeks, a percentage of patients with NVAF from a hypothetical cohort of 1000 will have an infarction. Some of these patients will die as a consequence of this complication and the remainder will survive. Those patients who have had an infarction complete the simulation at this time and are counted as failures in prevention, with the costs and utilities associated with the state of acute myocardial infarction.

Differences in the effectiveness of the treatments were measured in life years gained and in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) gained. The utilities of the different health states used to calculate the QALY were obtained from a study performed in the United Kingdom based on the EQ-5D (EuroQol 5D) questionnaire in patients with AF28,29 (Table 2). Determination of the loss of quality of life associated with the need for monitoring required by the use of acenocoumarol was based on a study by Gage et al30 (Table 2).

Utilities Considered in the Markov Model

| Item | Mean | References |

|---|---|---|

| Utilities of the Markov states | ||

| Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, baseline | 0.7270 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Minor strokea | 0.6151 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Moderate strokea | 0.5646 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Severe strokea | 0.5142 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Systemic embolism | 0.6265 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.6098 | Sullivan et al28 |

| Loss of utilities, duration | ||

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.1511 (6 weeks) | Sullivan et al28 |

| Other major bleeding | 0.1511 (2 weeks) | Sullivan et al28, Freeman et al29 |

| CRNM bleeding | 0.0582 (2 days) | Sullivan et al28, Freeman et al29 |

| Hospitalization for other CV-related causes | 0.1276 (6 days) | Sullivan et al28 |

| Use of acenocoumarol, INR monitoring | 0.0130 (treatment) | Sullivan et al28 |

| Use of apixaban | 0 | Assumptionb |

CV, cardiovascular; INR, international normalized ratio; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor.

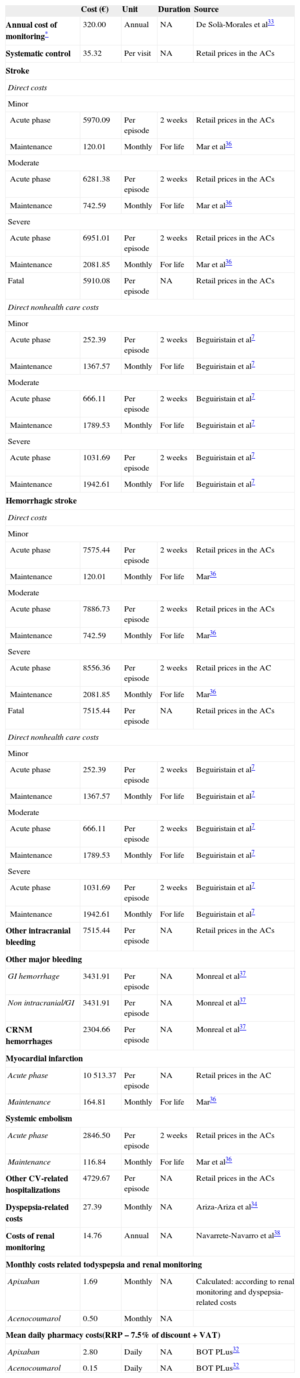

The per unit use and cost of resources were obtained from Spanish sources (in 2012 euros). The analysis was carried out from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (considering only the direct health care costs) and of society (including direct nonhealth care costs, as well). The cost of the medications (RRP [recommended retail price] + VAT [value added tax], with a 7.5% reduction)31 was calculated by considering 10 mg/day (5-mg doses twice daily) of apixaban32 and 5mg/day of acenocoumarol (the daily dose recommended by the World Health Organization). The cost of INR monitoring was estimated to be € 320 a year, according to a study by De Solà-Morales Serra and Elorza Ricart.33 It was considered that all the patients, regardless of their treatment, visited their primary care physician every 3 months for routine follow-up of the AF. The cost of the complications of NVAF during the acute phase was obtained by taking the mean of the retail prices corresponding to diagnosis-related groups in the Spanish autonomous communities; the cost of treatment after the acute phase of the complications was obtained from other Spanish sources7,34–38 (Table 3). The direct nonhealth care costs included in the analysis from the societal perspective consisted of those derived from informal care (aid to the dependent patient and home adaptations) of patients who have had an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke7 (Table 3). An annual discount rate of 3.5% was applied for health care costs and results.

Costs Considered in the Markov Model

| Cost (€) | Unit | Duration | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual cost of monitoring* | 320.00 | Annual | NA | De Solà-Morales et al33 |

| Systematic control | 35.32 | Per visit | NA | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Stroke | ||||

| Direct costs | ||||

| Minor | ||||

| Acute phase | 5970.09 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 120.01 | Monthly | For life | Mar et al36 |

| Moderate | ||||

| Acute phase | 6281.38 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 742.59 | Monthly | For life | Mar et al36 |

| Severe | ||||

| Acute phase | 6951.01 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 2081.85 | Monthly | For life | Mar et al36 |

| Fatal | 5910.08 | Per episode | NA | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Direct nonhealth care costs | ||||

| Minor | ||||

| Acute phase | 252.39 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1367.57 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Moderate | ||||

| Acute phase | 666.11 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1789.53 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Severe | ||||

| Acute phase | 1031.69 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1942.61 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | ||||

| Direct costs | ||||

| Minor | ||||

| Acute phase | 7575.44 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 120.01 | Monthly | For life | Mar36 |

| Moderate | ||||

| Acute phase | 7886.73 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 742.59 | Monthly | For life | Mar36 |

| Severe | ||||

| Acute phase | 8556.36 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the AC |

| Maintenance | 2081.85 | Monthly | For life | Mar36 |

| Fatal | 7515.44 | Per episode | NA | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Direct nonhealth care costs | ||||

| Minor | ||||

| Acute phase | 252.39 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1367.57 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Moderate | ||||

| Acute phase | 666.11 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1789.53 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Severe | ||||

| Acute phase | 1031.69 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Maintenance | 1942.61 | Monthly | For life | Beguiristain et al7 |

| Other intracranial bleeding | 7515.44 | Per episode | NA | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Other major bleeding | ||||

| GI hemorrhage | 3431.91 | Per episode | NA | Monreal et al37 |

| Non intracranial/GI | 3431.91 | Per episode | NA | Monreal et al37 |

| CRNM hemorrhages | 2304.66 | Per episode | NA | Monreal et al37 |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||

| Acute phase | 10 513.37 | Per episode | NA | Retail prices in the AC |

| Maintenance | 164.81 | Monthly | For life | Mar36 |

| Systemic embolism | ||||

| Acute phase | 2846.50 | Per episode | 2 weeks | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Maintenance | 116.84 | Monthly | For life | Mar et al36 |

| Other CV-related hospitalizations | 4729.67 | Per episode | NA | Retail prices in the ACs |

| Dyspepsia-related costs | 27.39 | Monthly | NA | Ariza-Ariza et al34 |

| Costs of renal monitoring | 14.76 | Annual | NA | Navarrete-Navarro et al38 |

| Monthly costs related todyspepsia and renal monitoring | ||||

| Apixaban | 1.69 | Monthly | NA | Calculated: according to renal monitoring and dyspepsia-related costs |

| Acenocoumarol | 0.50 | Monthly | NA | |

| Mean daily pharmacy costs(RRP – 7.5% of discount + VAT) | ||||

| Apixaban | 2.80 | Daily | NA | BOT PLus32 |

| Acenocoumarol | 0.15 | Daily | NA | BOT PLus32 |

ACs, autonomous communities; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; CV, cardiovascular; GI, gastrointestinal; NA, not applicable; RRP, recommended retail price; VAT, value added tax.

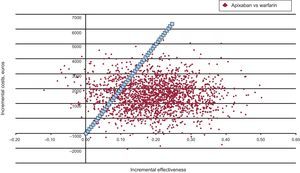

We analyzed a base case with the mean values of all the parameters. To confirm the stability of the results, simple univariate sensitivity analyses were performed (in each sensitivity analysis, the baseline value of a variable was modified, applying its extreme values) for the main variables of the model (Table 1). One of those analyzed was the percentage of TTR of the study population. According to the ARISTOTLE trial,16 in the base case of the analysis, 25% of the patients were equally distributed among the 4 established TTR intervals (< 52.38%; from ≥ 52.38% to < 66.02%; from ≥ 66.02% to < 76.51%, and ≥ 76.51%). In this respect, sensitivity analysis of the extreme values considering that 100% of the patients were in the worst (< 52.38% in TTR) or best (≥ 76.51% in TTR) of the intervals was carried out. Sensitivity analyses were also performed for acenocoumarol and apixaban, taking the extreme values of variables such as risk of stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, the probability of hospital admission, the cost of each visit for INR monitoring for acenocoumarol, and the loss of utilities associated with the use of acenocoumarol or apixaban (Figure 3). As the reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction vs warfarin was not statistically significant, a sensitivity analysis was carried out considering that apixaban did not reduce the number of myocardial infarctions vs warfarin, that is, taking the same rate of infarctions (0.530/100 person-years) for apixaban and warfarin. Finally, a probabilistic analysis was performed (Monte Carlo simulation with 2000 simulations in the 1000-patient cohort) which included, at the same time, all the variables of the analysis, adjusted for the appropriate statistical distributions in each case (beta for the transition probabilities and the utilities and gamma for costs). When the model simulated the course of a hypothetical cohort of 1000 patients with NVAF, the course of each patient in that cohort was different, since the modifications in all the variables of each patient (eg, the hazard ratio of stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, intracranial hemorrhage, costs, utilities, etc) occurred randomly in accordance with the previously defined statistical distributions. Thus, an attempt was made to imitate the real clinical course of the patients.

Deterministic sensitivity analysis from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System. Tornado diagram (the extreme values used are indicated to one side). Ratio of incremental cost-effectiveness (euros per quality-adjusted life years gained with apixaban vs acenocoumarol) (in 2012 euros). The figure shows the values of the base case and the extreme values used in the sensitivity analysis. The risks are expressed as rate/100 patient-years. Mortality is the rate of death during the clinical trial. CV, cardiovascular; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; TTR, time in therapeutic range.

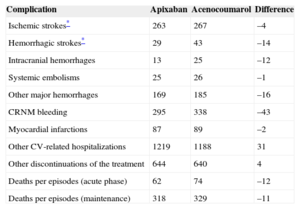

According to the results produced by the model applied to a cohort of 1000 patients with NVAF, apixaban would prevent a considerable number of complications compared with acenocoumarol: 18 strokes (4 ischemic and 14 hemorrhagic), 71 hemorrhages (12 of which would be intracranial and 16 would be cases of major bleeding), 1 systemic embolism, and 2 myocardial infarctions. In contrast, apixaban would prevent 23 deaths related to thromboembolic or hemorrhagic episodes (Table 4).

Number of Complications Predicted in the Life-long Follow-up of a Cohort of 1000 Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

| Complication | Apixaban | Acenocoumarol | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic strokes* | 263 | 267 | –4 |

| Hemorrhagic strokes* | 29 | 43 | –14 |

| Intracranial hemorrhages | 13 | 25 | –12 |

| Systemic embolisms | 25 | 26 | –1 |

| Other major hemorrhages | 169 | 185 | –16 |

| CRNM bleeding | 295 | 338 | –43 |

| Myocardial infarctions | 87 | 89 | –2 |

| Other CV-related hospitalizations | 1219 | 1188 | 31 |

| Other discontinuations of the treatment | 644 | 640 | 4 |

| Deaths per episodes (acute phase) | 62 | 74 | –12 |

| Deaths per episodes (maintenance) | 318 | 329 | –11 |

CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; CV, cardiovascular.

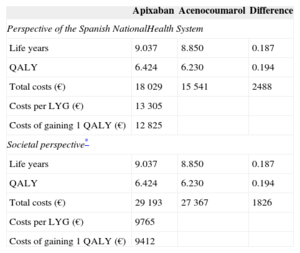

Consequently, for each patient treated with apixaban rather than acenocoumarol we would obtain more life years (0.187 life years gained) and an increase in QALY (0.194 gained). The incremental costs per patient treated with apixaban would be € 2488 for the Spanish National Health System and € 1826 for society. This difference in costs is mainly due to the more marked decrease in mortality obtained with apixaban and its higher purchase price. The cost per life years gained for the Spanish National Health System and for society was € 13 305 and € 9765, respectively. The cost per QALY gained was € 12 825 and € 9412, respectively (Table 5). These results indicate that, compared with acenocoumarol, apixaban is cost-effective in the prevention of stroke in patients with NVAF in Spain, as the costs per life years gained or for QALY gained are below € 30 000, which is the threshold that is generally accepted in Spain.39

Results of the Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Apixaban vs Acenocoumarol

| Apixaban | Acenocoumarol | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perspective of the Spanish NationalHealth System | |||

| Life years | 9.037 | 8.850 | 0.187 |

| QALY | 6.424 | 6.230 | 0.194 |

| Total costs (€) | 18 029 | 15 541 | 2488 |

| Costs per LYG (€) | 13 305 | ||

| Costs of gaining 1 QALY (€) | 12 825 | ||

| Societal perspective* | |||

| Life years | 9.037 | 8.850 | 0.187 |

| QALY | 6.424 | 6.230 | 0.194 |

| Total costs (€) | 29 193 | 27 367 | 1826 |

| Costs per LYG (€) | 9765 | ||

| Costs of gaining 1 QALY (€) | 9412 | ||

LYG, life year gained; QALY, quality adjusted life year.

The sensitivity analyses confirmed that apixaban is a cost-effective treatment compared with acenocoumarol. The changes in the most sensitive parameters of the study, such as the risks of complications with one treatment or the other, the loss of utilities associated with INR monitoring with acenocoumarol, and the costs of follow-up visits, do not affect the results of the analysis since, in every case, the costs of gaining 1 life year and the cost of gaining 1 QALY with the most effective treatment (apixaban) were below the threshold of € 30 000 (Figure 3).

Considering that 100% of the patients were in the lowest percentage of TTR (< 52.38%), the cost of gaining 1 QALY would be € 7054. In the opposite case (≥ 76.51% in TTR), the cost per QALY gained would increase to € 12 404, in both cases, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (Figure 3). Should apixaban fail to reduce the number of myocardial infarctions compared with warfarin, the cost of gaining 1 QALY would be € 14 150.

According to the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, the probability of apixaban being cost-effective vs acenocoumarol was 87% (Figure 4).

DISCUSSIONAlthough acenocoumarol and warfarin are the usual treatments for AF, their use has limitations owing to their narrow therapeutic margin, the risk of bleeding, and drug-drug and drug-food interactions.40,41 Patients treated with VKA require frequent INR monitoring and resulting dose adjustments. According to a meta-analysis by Baker et al,42 patients treated with warfarin remain in the therapeutic INR range only 55% of the time. Of anticoagulated patients who have a cardioembolic stroke, 67.6% have an INR below the therapeutic range at the time of the stroke.43

Apixaban is a new anticoagulant that produces a statistically significant reduction in the risks of stroke, bleeding, and death due to these episodes compared with VKA.40 In this respect, a study by Banerjee et al,44 based on patients treated in real-world clinical practice, indicates that the net clinical benefit (balance between the risk of ischemic stroke and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage) of apixaban is greater than that of warfarin, for different CHADS2 scores and risk of bleeding.

According to the present model and the adopted premises, apixaban can be a cost-effective treatment compared with acenocoumarol in the prevention of stroke in NVAF patients in Spain.

Limitations of the ModelIn the assessment of these results, we must take into account the fact that this is a theoretical model that is, by definition, a simplified simulation of reality. Pharmacoeconomic models enable the creation of economic simulations of complex drug-related health care processes. They are especially useful when the intention is to simulate the course of a disease beyond the period of clinical tests.17 Markov models with Monte Carlo simulation are preferred over deterministic models when dealing with chronic diseases like NVAF, as they are better at simulating the course of the disease over the long term. The Markov deterministic model is based on the course of a hypothetical patient cohort. However, the Monte Carlo probabilistic analysis simulates the course of individual patients, based on the values of randomly chosen variables, which more closely resembles clinical reality. The data on efficacy and on adverse effects utilized in the model were obtained from a randomized clinical trial involving 18 201 patients with NVAF,16 providing a high level of evidence.

One of the main suppositions of the model is the therapeutic equivalence between warfarin and acenocoumarol. Thus, we adopted the effectiveness values obtained for acenocoumarol in the ARISTOTLE clinical trial, which compared it with warfarin.16 This assumption can be considered a limitation of the study, given that, although the 2 drugs could have similar effectiveness in clinical practice,12 an observational study found no significant differences in the quality of INR control, but did report a longer duration of the TTR in the patients treated with acenocoumarol than in those treated with warfarin (37.6% vs 35.7%; P = .0002).13 Nevertheless, in other previously published Spanish economic studies, acenocoumarol and warfarin were considered to be perfect substitutes for each other, both in efficacy and safety and the in the resource use associated with each.45,46

The costs assumed for the acute phase of the strokes and hemorrhages in the model were obtained from the diagnosis-related groups published by the Spanish autonomous communities, prices that could differ from the real direct costs of the processes.

The cost of the drugs was calculated considering a dose of 5mg/d of acenocoumarol, the daily dose recommended by the World Health Organization. Nevertheless, it should be considered that this premise serves only for the calculation of the cost of treatment with acenocoumarol, a variable that does not significantly affect the result because of the low price of the drug.

The utilities of the model were obtained from a study performed in the United Kingdom based on the EQ-5D questionnaire in patients with AF.28,29 Concerning the validity of these utility data corresponding to the Spanish population, a study based on 83 000 evaluations of 44 health states, with the EQ-5D applied in 6 European countries (including Spain) observed wider variability between individuals than between countries.47

Despite the aforementioned limitations of the model, the results obtained concur, as the result favoring apixaban is maintained both in deterministic sensitivity analyses and in the Monte Carlo analysis, with a high probability (87%) that apixaban is more cost-effective than acenocoumarol.

The present report is the first analysis of the cost-effectiveness of apixaban in NVAF performed in Spain. Two analyses comparing the cost-effectiveness of apixaban and warfarin in NVAF have recently been published in the United States.48,49 These studies found that apixaban would be cost-effective in 98% and 62% of the simulations for primary and secondary stroke prevention, respectively.

Two economic analyses of oral anticoagulants vs acenocoumarol in the prevention of stroke in patients with NVAF in Spain have recently been published.45,46 From the perspective of the Spanish National Health System, the cost per QALY gained would be € 17 581 with dabigatran5 and € 11 274 with rivaroxaban.46 The results of the economic models of apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are not directly comparable, since they differ in the structure of the Markov models used; however, they reflect the fact that the oral anticoagulants available in Spain are cost-effective options in the current Spanish health care context.

CONCLUSIONSAccording to the premises assumed in this model, it can be concluded that it is highly probable (probability of 87% according to the probabilistic analysis) that apixaban could be a cost-effective treatment compared with acenocoumarol in the prevention of stroke in patients with NVAF, in accordance with the cost-effectiveness threshold generally accepted in Spain.39 The stability of the results obtained in the base case of the analysis were confirmed in the deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThis study was jointly financed by Bristol-Myers Squibb S.A. and Pfizer S.L.U. Lourdes Betegón and Cristina Canal are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb S.A. and Marina De Sales is employed by Pfizer S.L.U. The remaining authors have been remunerated by Bristol-Myers Squibb S.A. and Pfizer S.L.U. for their collaboration in matters of consultancy and editorial opinion.

The authors wish to thank Teresa Lanitis and Thitima Kongnakorn for their work in the development of the model used as the basis for the adaptation of the study to Spain.