The European Society of Cardiology guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention recommend cardiac rehabilitation for patients with acute coronary syndrome.1 Cardiac rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary program associated with lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, better health-related quality of life,1 and reduced health care costs.2 Cardioplan is a cardiac telerehabilitation (CTR) system that tracks everyday adherence to healthy heart habits in patients with acute coronary syndrome. In a randomized clinical trial (NCT04942977), we found that 10 months of CTR increased physical activity levels, favored a return to work, and improved adherence to the Mediterranean diet, emotional well-being, and inflammatory and lipid profiles compared with regular follow-up over the same period. Regular follow-up included 2 months of conventional center-based cardiac rehabilitation (CBCR).3,4

The aim of this study was to evaluate the cost-utility of prolonged CTR vs CBCR from a societal perspective (number of sick days and trips to the hospital) and the perspective of the Spanish national health system (NHS) (use of health care resources [visits, admissions, hospital tests, and rehabilitation sessions).

Fifty-nine patients who met the inclusion criteria and showed no differences in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics were randomized to receive CTR or CBCR. All patients provided signed informed consent and the study was approved by the ethics committee at Hospital Arnau de Vilanova in Valencia, Spain, and the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS). Patients in the CTR group (n=31) completed 4 educational and physical training sessions (walking and resistance training) at the hospital, where they were also instructed on the use of the Cardioplan smartphone application. This application was then used to monitor the different study variables at home and send messages promoting adherence to healthy lifestyle habits. Patients in the CBCR group (n=28) participated in 16 cardiac rehabilitation sessions at the hospital and underwent regular follow-up for a total of 10 months (see Dalli Peydró et al.3 for methods).

The effects of the CTR and CBCR interventions on patient quality of life were measured using the EuroQol 5-dimention 5-level survey (EQ-5D-5L).5 This tool provides a summary index value (utility index) that facilitates calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

Direct health care costs were calculated by multiplying resources consumed by unit costs. Additional costs considered in the CTR group were the annual license fee for the Cardioplan system and the cost of the support service.

QALYs were estimated using a regression model. The final values were calculated using the baseline index value obtained for each patient. The cost results (€2022) were grouped according to the 2 perspectives (societal and NHS).

Nonparametric sampling with replacement was used to assess uncertainty in the estimates and obtain 95%CIs. The results of the cost-utility analysis were reported using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (ratio between difference in costs and difference in QALYs between the CTR and CBCR interventions).

Adjusted mean QALYs were similar in the CTR and CBCR groups (0.929; 95%CI, 0.891-0.966 vs 0.931; 95%CI, 0.904-0.958). The differences in favor of CTR were not significant (mean, 0.002; 95% CI, –0.044 to 0.049).

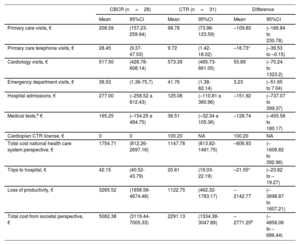

Mean costs per patient in each group and between-group differences are shown in table 1. It should be noted that the total cost from both the societal and NSH perspectives included in-hospital rehabilitation sessions (95% adherence in CTR group vs 76% in CBCR group). From the societal perspective, the CTR intervention resulted in significant savings in terms of primary care telephone visits, trips to the hospital, and total costs.

Summary of costs per patient (mean and 95%CIs obtained by nonparametric sampling with replacement)

| CBCR (n=28) | CTR (n=31) | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95%CI | Mean | 95%CI | Mean | 95%CI | |

| Primary care visits, € | 208.59 | (157.23-259.94) | 98.78 | (73.98-123.59) | –109.80 | (–166.84 to 230.78) |

| Primary care telephone visits, € | 28.45 | (9.37-47.53) | 9.72 | (1.42-18.02) | –18.73* | (–39.53 to –0.15) |

| Cardiology visits, € | 517.50 | (426.78-608.14) | 573.39 | (485.73-661.05) | 55.89 | (–70.24 to 1323.2) |

| Emergency department visits, € | 38.53 | (1.36-75.7) | 41.76 | (1.38-82.14) | 3.23 | (–51.65 to 7.04) |

| Hospital admissions, € | 277.00 | (–258.52 a 812.43) | 125.08 | (–110.81 a 360.96) | –151.92 | (–737.07 to 399.37) |

| Medical tests,a € | 165.25 | (–154.25 a 484.75) | 36.51 | (–32.34 a 105.36) | –128.74 | (–455.58 to 180.17) |

| Cardioplan CTR license, € | 0 | 0 | 100.20 | NA | 100.20 | NA |

| Total cost national health care system perspective, € | 1754.71 | (812.26-2697.16) | 1147.78 | (813.82-1481.75) | –606.93 | (–1606.82 to 392.96) |

| Trips to hospital, € | 42.15 | (40.52-43.79) | 20.61 | (19.03-22.19) | –21.55* | (–23.82 to –19.27) |

| Loss of productivity, € | 3265.52 | (1856.56-4674.48) | 1122.75 | (462.32-1783.17) | –2142.77 | (–3698.87 to 1607.21) |

| Total cost from societal perspective, € | 5062.38 | (3119.44-7005.33) | 2291.13 | (1534.38-3047.89) | –2771.25b | (–4856.06 to –686.44) |

CBCR, center-based cardiac rehabilitation; CTR, cardiac telerehabilitation; NA, nonapplicable.

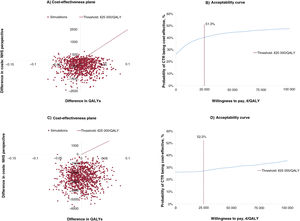

From the societal perspective, no significant differences were observed between the CTR and CBCR groups for either costs (mean, –606.93; 95%CI, –1606.82 to 392.96) or QALYs (mean, 0.002; 95%CI, 0.044 to –0.049). Because the mean cost difference was negative (greater savings with CTR vs CBCR) and the mean QALY difference was positive, the cost-utility result fell in the southeast (dominant) quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane (lower costs and more benefits for CTR), preventing calculation of the ICER. The QALY differences in the cost-effectiveness plane were around 0, while the cost differences were positioned slightly toward the negative part of the Y axis, indicating greater savings for CTR vs CBCR. The results show that CTR is a cost-effective option, depending on the threshold established. In other words, it was the dominant option from the perspective of the Spanish NHS in 51.3% of simulations (figure 1B).

Significant differences in favor of CTR were observed when costs were estimated from the societal perspective (mean, –2771.25; 95%CI, –4856.06 to –686.44). Both costs and QALYs were in the southeast quadrant, precluding again calculation of the ICER. The QALY differences in the simulations showed the same dispersion. The cost differences, by contrast, were positioned at the negative end of the Y axis (figure 1C). In this case, CTR was the dominant (cost-effective) option in 52.3% of the simulations (figure 1D).

Conceptual and technological innovations capable of overcoming existing barriers and methodological limitations are crucial for achieving a sustainable publicly-funded health care system. Prolonged CTR offers a flexible framework for incorporating patient preferences while enhancing self-care. The results of this cost-utility analysis show that prolonged telemonitoring with the CTR Cardioplan system yields cost savings for both society and the Spanish NHS while offering comparable or superior effectiveness to CBCR. In both scenarios, CTR was the dominant strategy.

FUNDINGFundación para el Fomento de la Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica de la Comunidad Valenciana (FISABIO). BOL00054.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll the authors contributed equally to this study. All the authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTA. Fresneda-Fresneda: no conflicts of interest. E. Dalli-Peydró: speaker's fees from Almirall, AMGEM, and Ferrer; consultancy fees from AMGEM; financial support for attending meetings and/or travel grants from Novartis; payment for the economic analysis. J. Cosín-Sales: speaker's fees from Almirall, AMGEM, Ferrer, Sanofi, and Daiichi-Sankyo; consultancy fees from AMGEM and Sanofi. M.T. Tuzón-Segarra: speaker's fees from Ferrer; financial support for attending meetings and/or travel grants from Novartis; payment for the economic analysis. N. Muñoz-Ramos: no conflicts of interest. M. Prades Martí: consultant at the independent scientific consultancy firm Outcomes’10, which received payment for performing the cost-effectiveness analysis and drafting the paper.