The implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a device used to treat patients with ventricular arrhythmias or who have high risk thereof. Infection of the ICD device is a rare but potentially lethal complication (0.8% incidence). Infection may occur in the area of the generator, in the subcutaneous route of the electrodes, or in the intravenous portion of the electrodes, with or without endocarditis. These infections can be treated using three approaches: antibiotics, complete removal of the device (medical treatment alone is associated with higher mortality and recurrence), and implantation of a new ICD in another location.1

Infections can be classified as early or late, depending on whether they develop within 60 days or more than 365 days after ICD implantation. Early infections are caused by intraoperative contamination or hematogenous seeding following surgery. Late infections are caused by episodes of transient bacteremia from any source or by skin erosions over the generator pocket.1

Currently, infectious antibiotic chemoprophylaxis is not recommended for patients with ICDs during procedures that may cause transient bacteremia.2

Regarding infectious endocarditis, blood cultures are an essential tool for diagnosis and treatment. In the last decade there have been marked changes in the microorganisms that cause infectious endocarditis, with a predominance of Staphylococcus aureus (20%) followed by streptococci, which classically occupied the top position.3 Moreover, in recent years, the use of trans-esophageal echocardiography in patients with suspected infectious endocarditis is increasingly frequent and early, which contributes to diagnosis of the disease.3

We report the case of an 81-year-old man with a fever of 2 months duration. The patient was initially considered to have a gallstone-related fever (choledocholithiasis and cholangitis), and was treated with antibiotics and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with removal of purulent content, and an ERCP follow-up examination, which showed no pus. Given the prolonged fever and the Escherichia coli-positive blood culture, thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed, revealing pulmonary micronodules suspected as septic emboli.

Since 2002 the patient had an ICD for ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia with poor hemodynamic tolerance. To rule out infection associated with the ICD, we performed transesophageal echocardiography, which proved inconclusive, showing an image in the right atrium that may correspond to the Eustachian valve or to vegetation.

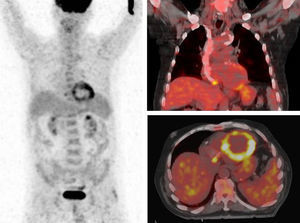

We requested positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose TC (18F-FDG PET-TC) to demonstrate a cardiac, respiratory, or biliary suppurative focus. A PET-CT body scan was performed one hour after intravenous administration of 6.6 mCi of 18F-FDG. The PET showed physiological uptake of 18F-FDG by the left ventricle and an active focus in the right atrium, which in the CT fusion image was located near the end of the ICD electrode (Figure). This was consistent with active infection at the end of the ICD electrode in the right atrium, and with the inconclusive image from the transesophageal echocardiography study. No other images indicated an active septic process. An additional inspiratory CT scan did not show the obvious pulmonary micronodules seen in the CT 2 weeks earlier, as these had been resolved by antibiotic treatment.

We considered that the electrode was infected with E. coli –an uncommon microbe in ICD infections (gram-negative bacilli such as E. coli cause 6% of infectious endocarditis) 3– due to an abdominal infection 2 months previously.

18F-FDG PET-TC is a morphofunctional scan that allows rapid, precise, and nonaggressive detection of the cause of a fever, since fluorodeoxyglucose may accumulate in sites of infection and inflammation as well as in tumour cells.4 Recently, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) have published joint guidelines on the application of 18F-FDG PET-TC in the diagnosis of infections. Its application in the detection of infection in patients with catheters, pacemakers, and intravascular devices is not yet established.5

This study reflects the potential offered by 18F-FDG PET-TC in the diagnosis of ICD electrode infection, allowing accurate detection of the septic focus.