Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is a serious, progressive disease that is more common than previously thought. Early diagnosis is crucial, as treatment can alter prognosis.1–3 CA can coexist with more common cardiomyopathies and remain unnoticed for years, affecting overall prognosis.4 Familiarity with the typical signs and symptoms of CA (red flags) can lead to an earlier diagnosis.1,2 We present 3 cases of CA that were not initially suspected.

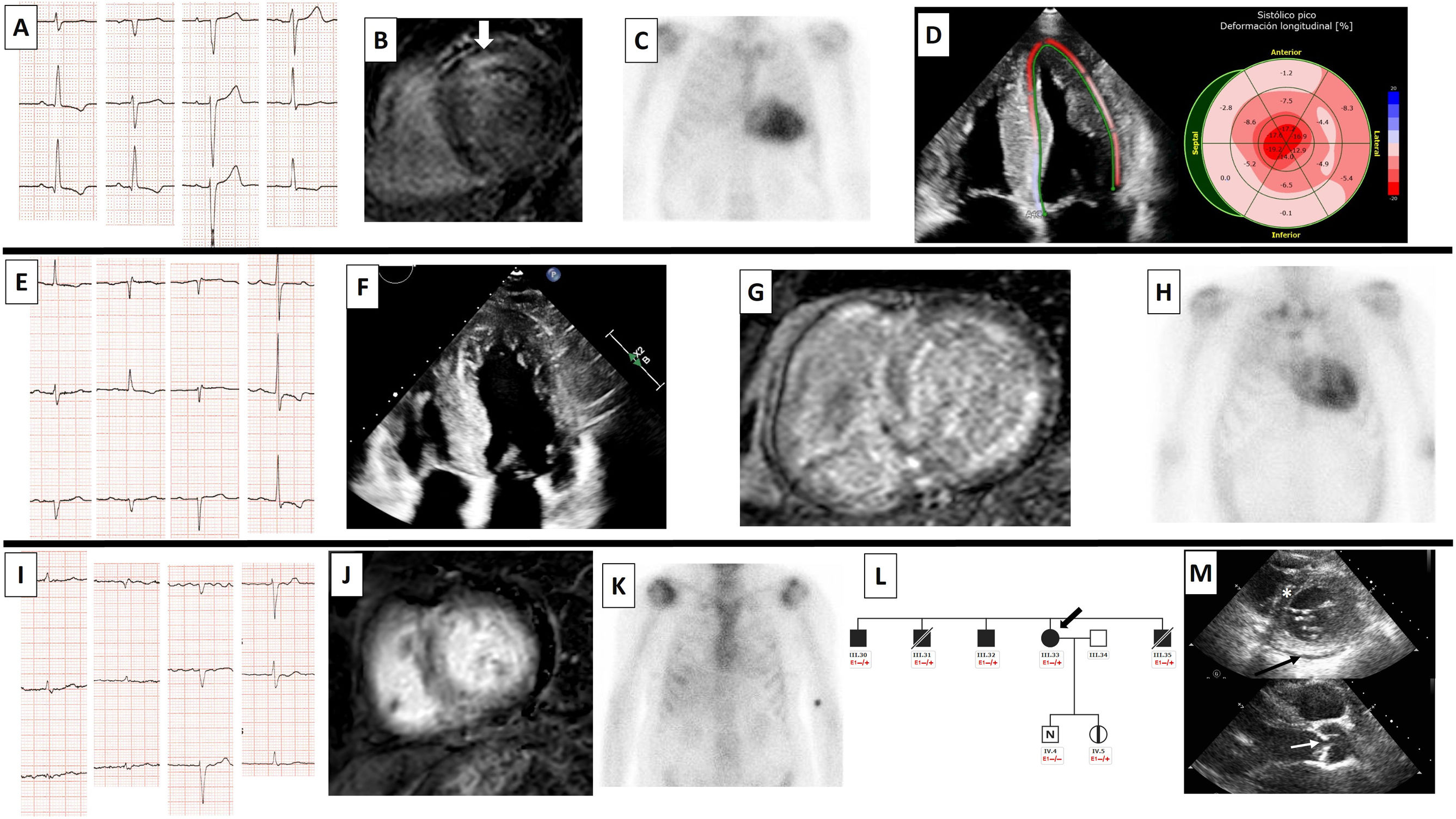

The first case involved a 73-year-old man with triple-vessel coronary artery disease treated with surgical revascularization. Following an echocardiogram showing left ventricular hypertrophy (20mm), the patient was referred for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which confirmed the hypertrophy and showed anteroseptal mesocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). There was no family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of sarcomeric genes and phenocopies detected a pathogenic variant in TNNC1 (p.Ala8Val), confirming the diagnosis of HCM. Family members underwent genetic testing, but no other cases of HCM were detected. During follow-up, the patient developed signs of heart failure with a typical CA strain pattern and the Popeye sign. He had recently undergone surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. A diagnosis of wild-type transthyretin (ATTRwt) CA was confirmed by technetium-99m-3,3-diphosphono-1,2 propanodicarboxylic acid (99mTc-DPD) scintigraphy (grade 3 uptake), while laboratory tests ruled out monoclonal proteins and genetic tests were negative. The patient developed a respiratory infection and died at the age of 79 years.

The second case of CA involved a 62-year-old hypertensive man with septal hypertrophy (15mm) that had been attributed to hypertension for years. When the patient was aged 74 years, he developed dyspnea on exertion. An echocardiogram showed hypertrophy (23mm), systolic anterior motion, and a subaortic gradient of 67mmHg with the Valsalva maneuver. The patient was referred to the family heart disease unit, where he underwent NGS of sarcomeric genes and phenocopies. The results showed a likely pathogenic variant in MYL3 (p.Met173Val), confirming the diagnosis of obstructive HCM. The patient was started on beta-blocker treatment, which relieved his obstructive symptoms. Genetic testing of family members detected no other cases of HCM. Two years later, the patient developed signs of heart failure, with an N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide fraction of 3000 pg/mL, a restrictive diastolic pattern on the echocardiogram, and the Popeye sign in the right arm (this deformity had not been previously present). Cardiac MRI showed abnormal gadolinium kinetics and diffuse LGE in both ventricles, while cardiac 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy showed grade 3 uptake. Monoclonal proteins were ruled out and the patient was diagnosed with ATTRwt CA. He is currently under follow-up at the outpatient clinic.

The third case of CA involved a 75-year-old woman with hypertension and a history of familial dilated cardiomyopathy due to a titin (TTN) variant (p.Trp19433*). She had atrial fibrillation with a nondilated left ventricle and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 30%. She was a carrier of a pathogenic familial TTN variant. Neurohormonal treatment increased LVEF to 50%. When she was 78 years old, the patient experienced clinical deterioration not attributable to the LVEF at the time and intolerance to neurohormonal antagonists due to hypotension. ECG findings included low voltages and the pseudoinfarct pattern; the echocardiogram showed mild pericardial effusion, moderate aortic stenosis, and a septal thickness of 12 mm. She underwent 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy, with uptake reported as grade 1-2, and laboratory tests, which ruled out monoclonal proteins. She refused to undergo biopsy for histologic confirmation. Cardiac MRI showed increased extracellular fluid volume and native T1 values, diffuse LGE, and abnormal gadolinium kinetics. Sanger sequencing of the TTR gene was negative. Based on the above findings, the patient was diagnosed with ATTRwt CA. She is currently under outpatient follow-up and has stable dyspnea on slight exertion.

The clinical characteristics of the 3 patients are summarized in table 1. Some of their test findings are shown in figure 1.

Patient characteristics

| Initial cardiomyopathy, age at diagnosis | Genetic variant identified | Pathogenicity of variant according to ACMG | Relatives studied/ variant carriers, No. | Amyloidosis red flags | 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy | EMB | Age at diagnosis of amyloidosis, y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Nonobstructive HCM (73 y) | TNNC1 (p.Ala8Val) | Pathogenic | 3/0 | • Popeye sign• Lumbar spinal stenosis• Reduced LGS with apical conservation | Grade 3 | Yes | 77 |

| Patient 2 | Obstructive HCM (74 y) | MYL3 (p.Met173Val) | Likely pathogenic | 1/0 | • Popeye sign• First-degree atrioventricular block• Diffuse LGE (MRI)• Abnormal gadolinium kinetics (MRI)• High native T1 (1123 ms; Philips Ingenia 1.50 T) (MRI)• Increased ECF volume (66%) (MRI) | Grade 3 | No | 78 |

| Patient 3 | Titin cardiomyopathy (76 y) | TTN (p.Trp19433*) | Pathogenic | 16/9 | • Carpal tunnel syndrome• Lumbar spinal stenosis• Hypotension in previously hypertensive patient• Pseudoinfarct pattern and low voltages on ECG• Aortic stenosis• Mild pericardial effusion• Diffuse LGE (MRI)• Abnormal gadolinium kinetics (MRI)• High native T1 (1103 ms; Philips Ingenia 1.50 T) (MRI)• Increased ECF volume (45%) (MRI) | Grade 1 | No | 78 |

99mTc-DPD, technetium-99m with 3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanedicarboxylic acid; ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECV, extracellular volume; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LGS, global longitudinal strain; LTR, late gadolinium enhancement; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Patient 1. A: ECG. B: cardiac MRI with anteroseptal mesocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) (white arrow). C: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. D: decreased global longitudinal strain with apical conservation. Patient 2. E: ECG. F: echocardiogram with apical 4-chamber views showing concentric thickening of left and right ventricles. G: cardiac MRI with abnormal gadolinium kinetics and diffuse, heterogeneous LGE in left and right ventricles. H: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. Patient 3. I: ECG with atrial fibrillation, low voltages, and pseudoinfarct pattern. J: cardiac MRI with diffuse LGE and abnormal gadolinium enhancement. K: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy with grade 1-2 uptake. L: section of the family tree (arrow, patient 3; black, relative with titin cardiomyopathy; black square, affected male relative; black circle, affected female relative; diagonal line, deceased relative; white square, healthy male relative; N, normal; vertical line, healthy carrier; E1 –/+, heterozygous for TTN variant [p.Trp19433*]; E1 –/–, noncarrier). M: upper image with echocardiogram showing septal hypertrophy of 12mm (asterisk) and mild pericardial effusion (arrow); lower image showing aortic valve thickening (arrow). 99mTc-DPD: technetium-99m with 3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanedicarboxylic acid; ECG: electrocardiogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; TTN, titin.

The 3 cases described in this report show that a previous diagnosis of cardiomyopathy does not rule out CA. All 3 patients had clinical and echocardiographic red flags for CA while under follow-up for HCM or titin cardiomyopathy. Cardiologists should always be alert to possible red flags for CA in patients older than 65 or 70 years, especially in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy or worsening symptoms.4–6 An existing diagnosis of cardiomyopathy should not preclude tests for CA, as both conditions can clearly coexist.

FUNDINGNo funding was received for this study.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONSApproval from the local ethics committee was not needed due to the characteristics of the study. The authors confirm that they received written informed consent from the patients for the publication of the text and images included in this article. Sex and gender were reported in accordance with the Spanish Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCENo artificial intelligence tools were used for this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSE. Martín-Álvarez, R. Barriales-Villa, and J.M. Larrañaga-Moreira designed the study, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. G. Barge-Caballero, M.G. Crespo-Leiro, and B. Souto-Caínzos critically reviewed the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. M. Larrañaga Moreira, M. G. Crespo Leiro, and R. Barriales Villa report have received funding from Pfizer for attending conferences.

M. G. Crespo Leiro received funding from Pfizer at her institute for participating in a clinical trial.

R. Barriales Villa has performed consultancy work for Pfizer, Alnylam, and Akcea.

![Patient 1. A: ECG. B: cardiac MRI with anteroseptal mesocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) (white arrow). C: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. D: decreased global longitudinal strain with apical conservation. Patient 2. E: ECG. F: echocardiogram with apical 4-chamber views showing concentric thickening of left and right ventricles. G: cardiac MRI with abnormal gadolinium kinetics and diffuse, heterogeneous LGE in left and right ventricles. H: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. Patient 3. I: ECG with atrial fibrillation, low voltages, and pseudoinfarct pattern. J: cardiac MRI with diffuse LGE and abnormal gadolinium enhancement. K: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy with grade 1-2 uptake. L: section of the family tree (arrow, patient 3; black, relative with titin cardiomyopathy; black square, affected male relative; black circle, affected female relative; diagonal line, deceased relative; white square, healthy male relative; N, normal; vertical line, healthy carrier; E1 –/+, heterozygous for TTN variant [p.Trp19433*]; E1 –/–, noncarrier). M: upper image with echocardiogram showing septal hypertrophy of 12mm (asterisk) and mild pericardial effusion (arrow); lower image showing aortic valve thickening (arrow). 99mTc-DPD: technetium-99m with 3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanedicarboxylic acid; ECG: electrocardiogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; TTN, titin. Patient 1. A: ECG. B: cardiac MRI with anteroseptal mesocardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) (white arrow). C: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. D: decreased global longitudinal strain with apical conservation. Patient 2. E: ECG. F: echocardiogram with apical 4-chamber views showing concentric thickening of left and right ventricles. G: cardiac MRI with abnormal gadolinium kinetics and diffuse, heterogeneous LGE in left and right ventricles. H: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy showing grade 3 uptake. Patient 3. I: ECG with atrial fibrillation, low voltages, and pseudoinfarct pattern. J: cardiac MRI with diffuse LGE and abnormal gadolinium enhancement. K: 99mTc-DPD cardiac scintigraphy with grade 1-2 uptake. L: section of the family tree (arrow, patient 3; black, relative with titin cardiomyopathy; black square, affected male relative; black circle, affected female relative; diagonal line, deceased relative; white square, healthy male relative; N, normal; vertical line, healthy carrier; E1 –/+, heterozygous for TTN variant [p.Trp19433*]; E1 –/–, noncarrier). M: upper image with echocardiogram showing septal hypertrophy of 12mm (asterisk) and mild pericardial effusion (arrow); lower image showing aortic valve thickening (arrow). 99mTc-DPD: technetium-99m with 3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanedicarboxylic acid; ECG: electrocardiogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; TTN, titin.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/18855857/0000007700000004/v2_202405080700/S1885585723003304/v2_202405080700/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=eyJpdiI6IjloNmN5a01rc0hqV1l4Ni9hK0syS0E9PSIsInZhbHVlIjoiM3FHK2FEQmNxQlEwbGZCZlBsUjU3Tzc0bU0rcTdNQ0ROdXBIS1hBSEdyUT0iLCJtYWMiOiIxY2ZiZTNhMzUxZTZlNGQwNDFlZGVjZWY3OGExYjE5ZTYzNzQ3YjQyZjM4NWRkZTBhMTM0MGQ2N2IyZWNjZDAzIiwidGFnIjoiIn0=)