Although percutaneous and surgical revascularizations have been shown to be beneficial in coronary artery disease, these procedures are not always feasible because of diffusely diseased vessels. There is little information on patients not eligible for revascularization because the inclusion criteria are usually expressed in subjective terms such as “refractory angina”, “severe diffuse disease”, or “anatomy not amenable to revascularization”, which results in wide heterogeneity. Even Medicare has no classification code for these patients, and the United States Task Force addressing this situation stresses the urgent need for studies.1

We analyzed the outcome of a cohort of patients with highly diffuse coronary artery disease who, on the basis of anatomic criteria, were not eligible for any type of revascularization. In December 2004, we selected all the patients who had been diagnosed as having 3-vessel disease since January 1999 in a hemodynamic referral center for 9 other hospitals. The coronary angiograms were reviewed by an interventional cardiologist and a cardiac surgeon, and those patients who were not considered candidates for any type of complete or incomplete revascularization constituted the study cohort. Those patients with valve disease that might have caused the symptoms were excluded. The clinical and angiographic data were collected from the database of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and the follow-up consisted of annual telephone calls made from December 2005 to December 2013. Information on patients who had died was obtained from their families or medical records.

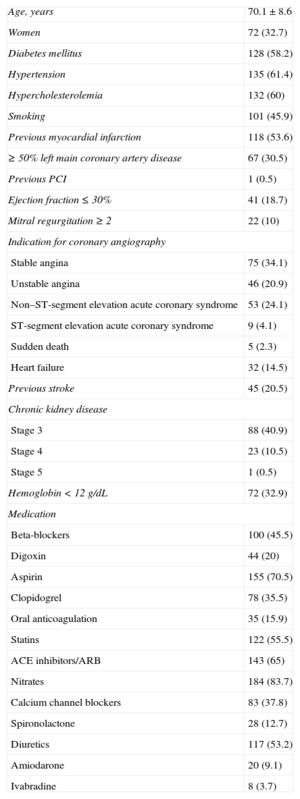

Between January 1999 and December 2004, coronary angiography was performed in 16 215 patients with suspected coronary artery disease; 3672 (22.6%) had 3-vessel disease. Of these, 220 were considered to be ineligible for complete or incomplete revascularization on the basis of anatomic criteria (5.9% of the patients with 3-vessel disease and 1.3% of the overall sample). The Table shows the clinical characteristics of these 220 patients and their medication.

Clinical Characteristics of the Patients and Medication Received (n=220)

| Age, years | 70.1±8.6 |

| Women | 72 (32.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 128 (58.2) |

| Hypertension | 135 (61.4) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 132 (60) |

| Smoking | 101 (45.9) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 118 (53.6) |

| ≥ 50% left main coronary artery disease | 67 (30.5) |

| Previous PCI | 1 (0.5) |

| Ejection fraction ≤ 30% | 41 (18.7) |

| Mitral regurgitation ≥ 2 | 22 (10) |

| Indication for coronary angiography | |

| Stable angina | 75 (34.1) |

| Unstable angina | 46 (20.9) |

| Non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome | 53 (24.1) |

| ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome | 9 (4.1) |

| Sudden death | 5 (2.3) |

| Heart failure | 32 (14.5) |

| Previous stroke | 45 (20.5) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |

| Stage 3 | 88 (40.9) |

| Stage 4 | 23 (10.5) |

| Stage 5 | 1 (0.5) |

| Hemoglobin < 12 g/dL | 72 (32.9) |

| Medication | |

| Beta-blockers | 100 (45.5) |

| Digoxin | 44 (20) |

| Aspirin | 155 (70.5) |

| Clopidogrel | 78 (35.5) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 35 (15.9) |

| Statins | 122 (55.5) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 143 (65) |

| Nitrates | 184 (83.7) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 83 (37.8) |

| Spironolactone | 28 (12.7) |

| Diuretics | 117 (53.2) |

| Amiodarone | 20 (9.1) |

| Ivabradine | 8 (3.7) |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

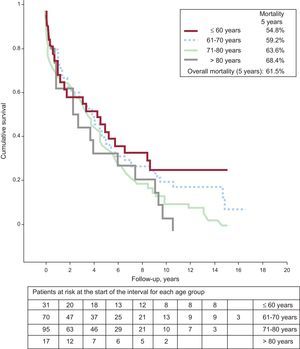

Follow-up information was obtained for 217 patients (98.6%); after 45.1 [interquartile range, 8.3-67.9] months, the overall mortality rate was very high (61.1% at 5 years). The Figure shows the survival curve according to age group. On Cox analysis, the predictors of 5-year mortality were age, previous myocardial infarction, ≥ 50% left main coronary artery disease, ejection fraction, mitral regurgitation ≥ 2, and hemoglobin concentration. The variables sex, creatinine clearance, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, atrial fibrillation, and left bundle branch block were excluded from the final model. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.77 (0.70-0.84; P<.001).

This report analyzed the outcome of a cohort of patients with different clinical manifestations of ischemic heart disease in whom the common denominator was an anatomy not amenable to revascularization. Mortality was notably higher than that in the general population, according to age groups provided by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics. For example, at the age of 70 years, the mean survival in the general population is 16.49 years and at age 80 years, 9.3%, clearly longer than the 4.47±0.45 years recorded in the 70- to 80-year-old patients in our series.2

The disparity in survival among the published series may be due to the differences in patient characteristics. In the series of Henry et al,3 in which the inclusion criterion was refractory angina or myocardial ischemia not amenable to revascularization, mortality was 3.9% at 1 year, 17.5% at 5 years, and 28.4% at 9 years, whereas in series in which the point of departure was the coronary anatomy, encompassing different clinical signs of ischemic heart disease, the mortality rate was much higher. In a series of 2776 patients with multivessel disease and an anatomy that made them ineligible for revascularization, the 5-year mortality was 37%.4 In another study involving patients with 3-vessel or left main coronary artery disease and ventricular function < 50%, 41% of the patients did not undergo revascularization and, 2.2 years later, 38% had died.5 Different inclusion criteria result in highly marked differences among the patients in the series. In that of Henry et al,3 in which the mean age was 63.5 years, 36.6% of the patients had diabetes, and 14.8% had chronic kidney disease, the cohort had a lower risk profile than the patients in our study, only 34.1% of whom had refractory angina.

The predictive variables identified in our report have been described in previous series. Diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease showed no statistically significant association, although an association would probably have been observed with a larger sample size. The lack of significance of these 2 variables could also be due to the inclusion criteria: in other series, both entities may have affected the prognosis because of their role in the progressive deterioration of the coronary anatomy. All the patients in our series, whether or not they have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, had a markedly deteriorated anatomy from the start.

As limitations, we cannot rule out possible subjectivity in the evaluation of the coronary angiographies. Secondly, analysis of medication is complex because of changes made during follow-up and modifications in the guidelines. However, despite the underuse of certain drugs, this series reflects daily practice during the study period, as the patients were referred from 9 different hospitals. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the variables considered included features that were associated with prognosis in previous series.

In conclusion, patients with severe diffuse coronary artery disease and an anatomy that is not amenable to revascularization represent a subgroup of patients with a very high mortality rate who all too seldom receive optimal medical treatment.