We have read the article by Barrios et al1 on the use of anticoagulation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation in an unselected population in primary care. We consider it a very important study because it highlights the great room for improvement in daily practice and that, regardless of the embolic risk scale chosen, about 45% of patients without an indication receive anticoagulation therapy (CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc score=0), whereas more than 40% of patients with a clear indication do not.

However, the reason for this letter concerns our disagreement with the authors’ statement that the CHA2DS2-VASc scale “...enables better identification of those patients with AF who will most benefit from anticoagulation therapy than the CHADS2 score”. Although it is true that when minor criteria (female sex, age 65-74 years, or vascular disease) are taken into account the predictive power of embolic events increases, we believe that basing the indication for anticoagulation therapy on these alone, in the absence of any major criterion, leads to many patients with a very low risk of embolism receiving anticoagulation therapy regardless of the net clinical benefit we wish to obtain (reducing thromboembolic risk while reducing severe bleeding risk). This idea is supported by information from a Danish registry on atrial fibrillation,2 which investigated reductions in the risk of stroke and intracranial bleeding. There was an evident lack of net clinical benefit in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score=1 and a very slight net clinical benefit in those with a CHADS2 score=1. This difference between the 2 scales can only be explained by the zero net clinical benefit of anticoagulation therapy in patients with a single minor criterion. In addition, when all the criteria are present anticoagulation therapy has an overall net clinical benefit in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score between 2 and 9. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether this would be maintained with a score of 2 or even 3 points if minor criteria alone were taken into account.

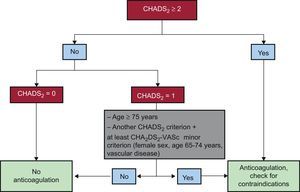

Therefore, it seems that the simplest solution based on scientific knowledge would be to maintain the indication for anticoagulation therapy according to CHADS2 criteria. This is in line with current evidence, while taking into account the words of caution expressed in the editorial comment in Revista Española de Cardiología3 concerning the guidelines for atrial fibrillation published by the European Society of Cardiology, as well as those published independently by its North American and Canadian counterparts, which did not take the CHA2DS2-VASc scale into account. However, the information provided by the new classification should be borne in mind in cases of doubtful net clinical benefit (some patients with CHADS2 scores=1). In this line, the recent study by Coppens et al4 showed that a significant percentage of patients (26%) with a CHADS2 score=1 (except age) have a very low risk of embolism (about 1% per year) unless they have any of the minor criteria included in the CHA2DS2-VASc scale. This raises doubts regarding the appropriateness of anticoagulation therapy in this subgroup. Thus, we propose the algorithm shown in the Figure: CHADS2=0, no anticoagulation; CHADS2 ≥ 2, anticoagulation (except in the case of absolute contraindication); CHADS2=1, anticoagulation when the criterion is age or there are minor criteria.

Finally, it should be borne in mind that the 4 studies on nonvalvular atrial fibrillation using the new oral anticoagulants based their indication for anticoagulation therapy on the CHADS2 classification. Therefore, it would not be justified to extrapolate their results and start anticoagulation with one of these drugs when the patient does not have any of the CHADS2 major criteria.