Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy in most patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). In these patients, adjuvant antithrombotic therapy (antiplatelet and anticoagulant) is essential to prevent thrombotic events mediated by platelet activation or the coagulation cascade.1 In pPCI, various parenteral anticoagulants are used, such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), enoxaparin and bivalirudin. However, the optimal time at which to start anticoagulation therapy in patients with STEMI–whether at diagnosis or at the start of pPCI–is unknown and consequently there are no recommendations on this issue in the current clinical practice guidelines.2,3 The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of early administration of anticoagulation therapy (at diagnosis) compared with its application in the cardiac catheterization laboratory at the start of the procedure on the initial patency of the infarct-related artery (IRA) in patients undergoing pPCI as a reperfusion strategy.

All consecutive patients (between October 2009 and November 2011) admitted to a tertiary center with a diagnosis of STEMI who underwent pPCI were prospectively registered. Patients diagnosed in the tertiary center and in other centers or by the emergency service in their homes and who were transported to the catheterization laboratory for pPCI were included. Patients who had received early enoxaparin therapy were excluded due to their small number and the heterogeneity of doses and routes of administration used. The patients were thus divided into 2 groups according to the treatment received at diagnosis (group 1: those receiving early UFH; group 2: those not receiving anticoagulation therapy until their arrival at the catheterization laboratory). The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and the anticoagulant employed in the catheterization laboratory (in patients in group 2) were used according to the operator's criteria. Once in the catheterization laboratory, group 1 patients underwent ACT (activated clotting time) determination and could receive an extra dose of UFH to achieve an ACT of 250-350 s (in those receiving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, the ACT target was 200-250 s), while group 2 patients received intravenous UFH doses of 1 mg/kg, except for 8% of the patients, who received bivalirudin. The patency of the IRA was evaluated with the initial Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade dichotomized into 2 arbitrary categories: poor flow (TIMI 0-1) vs good flow (TIMI 2-3). This categorization was used because TIMI grade 2-3 flow allows complete visualization of the distal area of the lesion, facilitating the procedure. The statistical analysis was performed by using a logistic regression model (backward stepwise method), which included initial TIMI flow (dichotomized) as the dependent variable and anticoagulation therapy (groups 1-2) as the independent variable, adjusting by variables considered clinically relevant and baseline characteristics not evenly distributed between the 2 groups (P<.20).

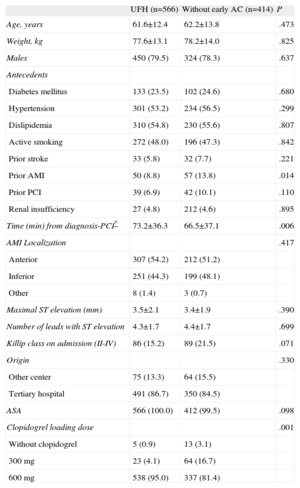

A total of 1075 patients were included, of which 95 were excluded because they had received early enoxaparin therapy. Therefore, 980 patients were included in this analysis, divided into the following 2 groups: group 1, n=566 (intravenous UFH 0.75-1 mg/kg), and group 2, n=414. None of the patients received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors before reaching the hospital. Among the baseline characteristics (Table), differences were found in the following variables (included in the model): prior acute myocardial infarction, prior PCI, Killip class on admission, clopidogrel loading dose, and the time between activation of the catheterization laboratory to the start of coronary angiography. In the multivariable analysis, the only predictor was the early use of UFH, which was associated with a significantly higher percentage of TIMI 2-3 flow in the IRA (27% vs 16.7%; odds ratio=1.84 [confidence interval, 1.33-2.55]; P<.001), in both cases compared with administration in the catheterization laboratory.

Characteristics Prior to Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

| UFH (n=566) | Without early AC (n=414) | P | |

| Age, years | 61.6±12.4 | 62.2±13.8 | .473 |

| Weight, kg | 77.6±13.1 | 78.2±14.0 | .825 |

| Males | 450 (79.5) | 324 (78.3) | .637 |

| Antecedents | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 133 (23.5) | 102 (24.6) | .680 |

| Hypertension | 301 (53.2) | 234 (56.5) | .299 |

| Dislipidemia | 310 (54.8) | 230 (55.6) | .807 |

| Active smoking | 272 (48.0) | 196 (47.3) | .842 |

| Prior stroke | 33 (5.8) | 32 (7.7) | .221 |

| Prior AMI | 50 (8.8) | 57 (13.8) | .014 |

| Prior PCI | 39 (6.9) | 42 (10.1) | .110 |

| Renal insufficiency | 27 (4.8) | 212 (4.6) | .895 |

| Time (min) from diagnosis-PCI* | 73.2±36.3 | 66.5±37.1 | .006 |

| AMI Localization | .417 | ||

| Anterior | 307 (54.2) | 212 (51.2) | |

| Inferior | 251 (44.3) | 199 (48.1) | |

| Other | 8 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Maximal ST elevation (mm) | 3.5±2.1 | 3.4±1.9 | .390 |

| Number of leads with ST elevation | 4.3±1.7 | 4.4±1.7 | .699 |

| Killip class on admission (II-IV) | 86 (15.2) | 89 (21.5) | .071 |

| Origin | .330 | ||

| Other center | 75 (13.3) | 64 (15.5) | |

| Tertiary hospital | 491 (86.7) | 350 (84.5) | |

| ASA | 566 (100.0) | 412 (99.5) | .098 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose | .001 | ||

| Without clopidogrel | 5 (0.9) | 13 (3.1) | |

| 300 mg | 23 (4.1) | 64 (16.7) | |

| 600 mg | 538 (95.0) | 337 (81.4) |

AC, anticoagulation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

The results of this study show that, in patients with STEMI undergoing pPCI, early administration of parenteral anticoagulation therapy (at diagnosis and before transfer to the catheterization laboratory) was associated with greater patency of the IRA on starting the procedure than initiating anticoagulation in the catheterization laboratory. The most important and novel characteristic of the present study is that it directly compares 2 anticoagulant administration strategies (early administration and administration at the start of pPCI), while previous studies have focused on comparing distinct agents rather than the optimal timing of administration.4–6

We acknowledge the limitations of this study due to its observational design; in addition, the possibility of a selection bias when administering early anticoagulation therapy cannot be excluded. To confirm our results, a randomized study should be performed. Such a study is warranted by the clinical implications of our findings.

Conflicts of interestDr. José Luis Ferreiro has received honoraria for conferences sponsored by Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly Co. and Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.