Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis is a rare disease1 with little more than 150 cases reported in the literature and less than a dozen with prosthetic valve involvement. However, this microorganism has been isolated in around 5%2,3 of cases of culture-negative infectious endocarditis, and so its active search is recommended in subacute or chronic endocarditis in which it may be involved.

With the explicit informed consent of the patient, we present the case of a 75-year-old asymptomatic woman with a history of atrial fibrillation, biological mitral valve replacement for severe double mitral lesion, tricuspid annuloplasty, and a single-chamber pacemaker for complete atrioventricular block after surgery 11 months earlier. The patient was transferred to our hospital because a sessile structure was found over the prosthetic valve during routine examination.

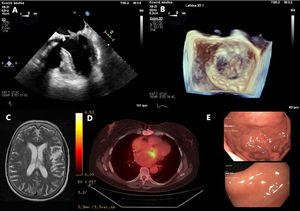

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms showed a hyperechogenic pedunculated structure with free movement through the mitral prosthesis, with a maximum length of more than 1 cm (figure 1A,B), without functional repercussions. Blood analysis showed slightly elevated inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein, 52 mg/L; leukocytes, 11 590/L; glomerular sedimentation rate, 51mm). Given the suspicion of early prosthetic endocarditis, blood and urine cultures were obtained and a cranial MRI was performed, which ruled out septic embolism (a residual ischemic lesion was found; figure 1C). Positron emission tomography showed metabolic activity compatible with mitral valve infective endocarditis (figure 1D).

A: transesophageal echocardiogram at 0° showing a pedunculated lesion on the atrial side of the biological mitral valve prosthesis. B: 3-dimensional view of the lesion from the atrial side. C: cranial magnetic resonance imaging with residual left parietal ischemic lesion without septic embolism. D: positron emission tomography showing marked metabolic activity at the level of the prosthetic mitral valve. E: endoscopy with gastric (upper image) and duodenal (lower image) mucosa without erosions.

Negative cultures prompted an exhaustive search for etiologic agents implicated in culture-negative endocarditis. Serologic tests for atypical microorganisms were negative and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for T ropheryma whipplei DNA was positive in stool. Previous studies have described potential asymptomatic colonization by the microorganism, which reduces the specificity of this test in patients without clinical symptoms compatible with Whipple's disease.4 Therefore, endoscopies were conducted for intestinal involvement, which showed healthy gastrointestinal mucosa (figure 1E) and no evidence characteristic of periodic acid-Schiff-positive granules in the histological specimen from the second duodenal portion. The PCR test was repeated in saliva, stool, blood, and urine, and again the result was positive in stool.

Despite the absence of clinical manifestations compatible with Whipple's disease, empirical antimicrobial treatment for endocarditis that also targeted the microorganism was initiated based on the high probability of infective endocarditis on positron emission tomography, the possibility of isolated valvular involvement as described in the literature,5 and the detection of T. whipplei DNA in 2 separate stool samples.

We chose an empirical regimen of gentamicin, daptomycin, and ceftriaxone for 4 weeks and suppressive treatment with cotrimoxazole for 1 year. Although the European guidelines on antimicrobial treatment for Whipple's disease recommend doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine, the relapses described after standard treatment with ceftriaxone and cotrimoxazole appear to be related to resistance to the second compound. A retrospective Spanish national review showed no difference between the 2 regimens2 and the broader spectrum of ceftriaxone within an empirical regimen led to its selection as the most appropriate treatment for the patient.

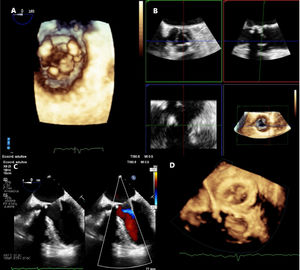

Two weeks after initiating treatment, transesophageal echocardiogram showed a stable lesion (figure 2A) without other valvular involvement (figure 2B). We decided to maintain antimicrobial therapy on the basis of these results and the published evidence on T. whipplei pulmonary hypertension or endocarditis6 that had been resolved without surgical treatment. The aminoglycoside was replaced by ciprofloxacin due to nephrotoxicity and daptomycin was replaced by linezolid due to probable pneumonitis. Thus, the combined antimicrobial therapy was prolonged for 6 weeks and then cotrimoxazole was continued as monotherapy until completion of 1 year of treatment. Four months after the start of antimicrobial treatment, there was a clear decrease in the size of the lesion (figure 2C,D). Blood analysis showed the gradual normalization of inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein, 1.2mg/L; leukocytes, 7,740/L; glomerular sedimentation rate, 9mm). To date, this is the first known case of early prosthetic endocarditis due to T. whipplei with no evidence of disease progression and a decrease in the size of the endocardial lesion through antimicrobial treatment alone.

A: 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (ventricular view) showing the lesion with a similar size. B: absence of native aortic valve involvement in orthogonal views. C: decrease in lesion size on transesophageal echocardiography at 0° with and without color. D: 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography; size of the lesion is smaller on the atrial side.

None declared.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSA. García-Olea and G. Ramírez-Escudero were the main authors. N. García, M. de la Peña, and L. Ruiz corrected different versions of the manuscript, provided critical review, and actively contributed to the selection of the audiovisual material.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.