Transaxillary access (TXA) has become the most widely used alternative to transfemoral access (TFA) in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). The aim of this study was to compare total in-hospital and 30-day mortality in patients included in the Spanish TAVI registry who were treated by TXA or TFA access.

MethodsWe analyzed data from patients treated with TXA or TFA and who were included in the TAVI Spanish registry. In-hospital and 30-day events were defined according to the recommendations of the Valve Academic Research Consortium. The impact of the access route was evaluated by propensity score matching according to clinical and echocardiogram characteristics.

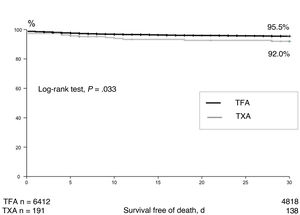

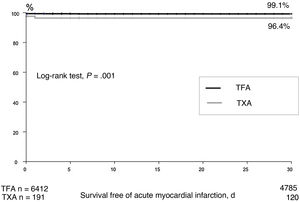

ResultsA total of 6603 patients were included; 191 (2.9%) were treated via TXA and 6412 via TFA access. After adjustment (n=113 TXA group and n=3035 TFA group) device success was similar between the 2 groups (94%, TXA vs 95%, TFA; P=.95). However, compared with the TFA group, the TXA group showed a higher rate of acute myocardial infarction (OR, 5.3; 95%CI, 2.0-13.8); P=.001), renal complications (OR, 2.3; 95%CI, 1.3-4.1; P=.003), and pacemaker implantation (OR, 1.6; 95%CI, 1.01-2.6; P=.03). The TXA group also had higher in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates (OR, 2.2; 95%CI, 1.04-4.6; P=.039 and OR, 2.3; 95%CI, 1.2-4.5; P=.01, respectively).

ConclusionsCompared with ATF, TXA is associated with higher total mortality, both in-hospital and at 30 days. Given these results, we believe that TXA should be considered only in those patients who are not suitable candidates for TFA.

Keywords

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become an alternative to surgery for the treatment of degenerative aortic valve disease.1,2 Transfemoral access (TFA) is the preferred route for TAVI and has been used in approximately 70% to 80% of cases since the first trials demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this procedure in high-risk patients.3,4 Despite the appearance of new-generation valves with smaller delivery devices, alternative access routes were still needed when TFA was not feasible. While the PARTNER I trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve Trial) used an exclusively transapical approach in its first cohort (Cohort A),5 the CoreValve trial used both a transaxillary (TFA) and a transaortic approach.6 TFA remains unfeasible in approximately 7% to 10% of patients treated with TAVI,7,8 and TXA would appear to be a good alternative.9 One meta-analysis of outcomes in 10 528 patients treated with TAVI reported comparable in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates for TFA and TXA,8 although the latter route was associated with higher mortality in the mid- and long-term. The authors also detected higher mortality in patients treated via TXA vs other routes (eg, transapical and transaortic). Another meta-analysis comparing TXA and TFA in 4500 patients detected no differences in mortality after 30 days or 12 months.10 The main aim of this study was to compare early mortality rates in unselected patients treated with TAVI via TFA or TXA (figure 1 and figure 2).

The Spanish TAVI registry, an initiative of the Interventional Cardiology Association (ICA) of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, is a prospective registry of data from 45 Spanish centers that perform TAVI.11 Participation in the registry is voluntary. The data are recorded in a dedicated, centralized online database accessible through the ICA website.12 To ensure compliance with rigorous security standards and guarantee the validity of the data, each researcher is assigned a unique username and password to enter patient data. Centers with their own database send data in a specific format through a secure channel. All data are anonymized and each patient is assigned a code in accordance with current data protection regulations. There are no formal audits, but the database is systematically and periodically checked for discrepancies and missing data.

All consecutive patients treated with TAVI added to the registry between 2009 and 2019 were included in this study. Patients who underwent transaortic (n = 56) or transapical TAVI (n = 568) were excluded. Clinical, procedural, and echocardiographic data were collected prospectively from the cardiology and cardiac surgery departments.

Events were defined according to the recommendations of the Valve Academic Research Consortium13 for patients included from 2009 to 2013 and the recommendations of the Valve Academic Research Consortium II14 for patients included from 2014 to 2019. Clinical follow-up data were obtained from all participating hospitals during clinical visits or by telephone. All patients provided signed informed consent before TAVI. The study was approved by the lead ethics committee (21/385-E).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as mean±SD and qualitative variables as numbers and percentages. Discrete variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test. To minimize confounding bias, the impact of the access route used was evaluated by propensity score matching (k-nearest neighbor matching, PSmatch2, Stata, StataCorp, USA) to select patients in the TXA group who were most likely to match those in the TFA group for the selected study variables. Variables showing differences (P ≤ .05) between the TXA and TFA groups were selected for the propensity score matching analysis, thereby ensuring that the 2 groups were balanced for all variables: those that showed no differences before matching and those that did show differences and were subsequently matched. Preprocedural variables only were considered. The propensity score thus does not take into account TAVI-related angiographic or hemodynamic variables. Propensity scores were generated using the PSmatch2 command and the k-nearest neighbor option. They were estimated using logistic regression with a maximum permitted difference (caliper) of 0.05 standard deviations and no replacement. The caliper method defines a common support region and discards scores outside the established interval. A 1:M match is not created. Rather, a patient from the TXA group is used several times as a match. This ensures that the overall scores in both groups are balanced and it also increases the average quality of the match and reduces bias. This is the most suitable method when working with data where the distribution of propensity scores differs considerably between comparison groups. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated. Collinearity with peripheral vascular disease (PVD) was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), as the collin comand in Stata identified an association between PVD and access route. The resulting VIF was less than 2 (1.8), ruling out severe multicollinearity problems. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted in which PVD was assumed to be associated with TXA but not with TFA. The resulting sensitivity was 75.43%. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. A logistic regression model was built to identify independent predictors of event-related mortality. Clinically relevant variables and variables with a significance of P<.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into the model, which was built using stepwise backward regression with an elimination probability of 0.10. The year 2014 was entered as a clinically relevant variant as an earlier study of patients from the same registry had shown higher mortality in patients treated with TAVI before 2014 (2009-2013).11 Statistical analyses were performed in Stata 13 and SPSS 21.0 (IBM, USA).

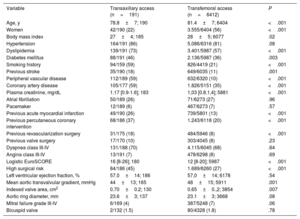

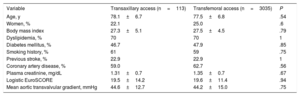

ResultsBaseline characteristicsWe included 6603 patients treated with TAVI: 191 (2.9%) via TXA (2.9%) and 6412 via TFA (87.1%). Their baseline (prematching) clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. Patients in the TXA group were younger and less likely to be women. They also had more cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (eg, a history of stroke and coronary heart disease), higher plasma creatinine levels, a higher logistic EuroSCORE, a lower mean aortic transvalvular gradient, and a larger indexed aortic valve area. The following variables were included in the propensity score matching analysis: age, female sex, smoking history, body mass index, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, coronary artery disease, plasma creatinine level, logistic EuroSCORE, and pre-TAVI mean aortic transvalvular gradient. The variables after matching are shown in table 2. Both the descriptive analysis and the results of the hypothesis testing confirm the absence of significant differences between the TXA and TFA groups.

Baseline (prematching) clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients included in the study

| Variable | Transaxillary access (n=191) | Transfemoral access (n=6412) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 78.8±7; 190 | 81.4±7; 6404 | <.001 |

| Women | 42/190 (22) | 3.555/6404 (56) | <.001 |

| Body mass index | 27±4; 185 | 28±5; 6077 | .02 |

| Hypertension | 164/191 (86) | 5.086/6316 (81) | .08 |

| Dyslipidemia | 139/191 (73) | 3.401/5987 (57) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 88/191 (46) | 2.136/5987 (36) | .003 |

| Smoking history | 94/159 (59) | 826/4419 (21) | <.001 |

| Previous stroke | 35/190 (18) | 649/6035 (11) | .001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 112/189 (59) | 632/6320 (10) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 105/177 (59) | 1.826/5151 (35) | <.001 |

| Plasma creatinine, mg/dL | 1.17 [0.9-1.6]; 183 | 1,03 [0.8.1,4]; 5881 | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 50/189 (26) | 71/6273 (27) | .96 |

| Pacemaker | 12/189 (6) | 467/6273 (7) | .57 |

| Previous acute myocardial infarction | 49/190 (26) | 739/5801 (13) | <.001 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 68/186 (37) | 1.243/6118 (20) | <.001 |

| Previous revascularization surgery | 31/175 (18) | 484/5946 (8) | <.001 |

| Previous valve surgery | 17/170 (10) | 303/4045 (8) | .23 |

| Dyspnea class III-IV | 131/188 (70) | 4.115/6045 (68) | .64 |

| Angina class III-IV | 13/191 (7) | 478/6298 (8) | .69 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 16 [8-26]; 180 | 12 [8-20]; 5987 | <.001 |

| High surgical risk | 84/186 (45) | 1.689/6260 (27) | <.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 57.0±14; 186 | 57,0±14; 6178 | .54 |

| Mean aortic transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 44±13; 165 | 48±15; 5911 | .001 |

| Indexed valve area, cm2 | 0.70±0.2; 130 | 0.65±0.,2; 3854 | .007 |

| Aortic ring diameter, mm | 23.6±3; 137 | 23.1±3; 3668 | .08 |

| Mitral failure grade III-IV | 6/169 (4) | 387/5248 (7) | .06 |

| Bicuspid valve | 2/132 (1.5) | 80/4328 (1.8) | .78 |

Values are expressed as No./total No. (%) and mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]; total No.

Clinical and ultrasound variables used for propensity score matching (after matching)

| Variable | Transaxillary access (n=113) | Transfemoral access (n=3035) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 78.1±6.7 | 77.5±6.8 | .54 |

| Women, % | 22.1 | 25.0 | .6 |

| Body mass index | 27.3±5.1 | 27.5±4.5 | .79 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 70 | 70 | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 46.7 | 47.9 | .85 |

| Smoking history, % | 61 | 59 | .75 |

| Previous stroke, % | 22.9 | 22.9 | 1 |

| Coronary artery disease, % | 59.0 | 62.7 | .56 |

| Plasma creatinine, mg/dL | 1.31±0.7 | 1.35±0.7 | .67 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 19.5±14.2 | 19.6±11.4 | .94 |

| Mean aortic transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 44.6±12.7 | 44.2±15.0 | .75 |

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

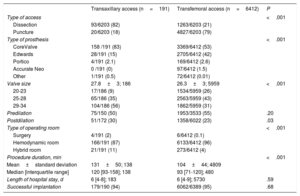

Access was achieved by surgical dissection in 82% of TXA-TAVI procedures and 21% of TFA-TAVI procedures. Self-expanding valves were used in 83% of patients in the TXA group and 53% of patients in the TFA group. Balloon-expandable valves were used in 15% and 42% of the patients, respectively. The procedure was performed in a hybrid operating room in 11% of TXA-TAVI procedures and 4% of TFA-TAXI procedures. Patients in the TXA group had significantly higher postdilation rates and longer procedures. Device implantation was successful in a similar proportion of patients in both groups (table 3).

Procedure characteristics

| Transaxillary access (n=191) | Transfemoral access (n=6412) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of access | <.001 | ||

| Dissection | 93/6203 (82) | 1263/6203 (21) | |

| Puncture | 20/6203 (18) | 4827/6203 (79) | |

| Type of prosthesis | <.001 | ||

| CoreValve | 158 /191 (83) | 3369/6412 (53) | |

| Edwards | 28/191 (15) | 2705/6412 (42) | |

| Portico | 4/191 (2.1) | 169/6412 (2.6) | |

| Accurate Neo | 0 /191 (0) | 97/6412 (1.5) | |

| Other | 1/191 (0.5) | 72/6412 (0.01) | |

| Valve size | 27.8±3; 186 | 26.3±3; 5959 | <.001 |

| 20-23 | 17/186 (9) | 1534/5959 (26) | |

| 25-28 | 65/186 (35) | 2563/5959 (43) | |

| 29-34 | 104/186 (56) | 1862/5959 (31) | |

| Predilation | 75/150 (50) | 1953/3533 (55) | .20 |

| Postdilation | 51/172 (30) | 1358/6022 (23) | .03 |

| Type of operating room | <.001 | ||

| Surgery | 4/191 (2) | 6/6412 (0.1) | |

| Hemodynamic room | 166/191 (87) | 6133/6412 (96) | |

| Hybrid room | 21/191 (11) | 273/6412 (4) | |

| Procedure duration, min | <.001 | ||

| Mean±standard deviation | 131±50; 138 | 104±44; 4809 | |

| Median [interquartile range] | 120 [93-158]; 138 | 93 [71-120]; 480 | |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 6 [4-8]; 183 | 6 [4-9]; 5730 | .59 |

| Successful implantation | 179/190 (94) | 6062/6389 (95) | .68 |

Values are expressed as n/N (%) and mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]; total No.

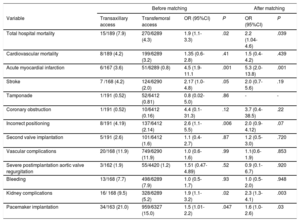

Comparison of in-hospital outcomes between patients in the TXA and TFA groups showed that patients who underwent TAVI via TXA were significantly more likely to die of any cause (OR,2.2; 95%CI, 1.04-4.6; P=.039), experience acute myocardial infarction (OR,5.3; 95%CI, 2.0-13.8; P=.001) or general kidney complications (OR,2.3; 95%CI, 1.3-4.1; P=.003), and require pacemaker implantation (OR,1.56; 95%CI, 1.0-2.6; P=.03). These differences were observed before and after matching (table 4). No differences were observed for stroke, vascular complications, or bleeding rates.

Hospital events

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Transaxillary access | Transfemoral access | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Total hospital mortality | 15/189 (7.9) | 270/6289 (4.3) | 1.9 (1.1-3.3) | .02 | 2.2 (1.04-4.6) | .039 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 8/189 (4.2) | 199/6289 (3.2) | 1.35 (0.6-2.8) | .41 | 1.5 (0.4-4.2) | .439 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 6/167 (3.6) | 51/6289 (0.8) | 4.5 (1.9-11.1 | .001 | 5.3 (2.0-13.8) | .001 |

| Stroke | 7 /168 (4.2) | 124/6290 (2.0) | 2.17 (1.0-4.8) | .05 | 2.0 (0.7- 5.6) | .19 |

| Tamponade | 1/191 (0.52) | 52/6412 (0.81) | 0.8 (0.02-5.0) | .86 | - | - |

| Coronary obstruction | 1/191 (0.52) | 10/6412 (0.16) | 4.4 (0.1-31.3) | .12 | 3.7 (0.4-38.5) | .22 |

| Incorrect positioning | 8/191 (4.19) | 137/6412 (2.14) | 2.6 (1.1-5.5) | .006 | 2.0 (0.9-4.12) | .07 |

| Second valve implantation | 5/191 (2.6) | 101/6412 (1.6) | 1.1 (0.4-2.7) | .87 | 1.2 (0.5-3.0) | .720 |

| Vascular complications | 20/168 (11.9) | 749/6290 (11.9) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | .99 | 1.1(0.6-1.9) | .853 |

| Severe postimplantation aortic valve regurgitation | 3/162 (1.9) | 55/4420 (1.2) | 1.51 (0.47-4.89) | .52 | 0.9 (0.1-6.7) | .920 |

| Bleeding | 13/168 (7.7) | 498/6289 (7.9) | 1.0 (0.5-1.7) | .93 | 1.0 (0.5-2.0) | .948 |

| Kidney complications | 16/ 168 (9.5) | 328/6289 (5.2) | 1.9 (1.1-3.2) | .02 | 2.3 (1.3-4.1) | .003 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 34/163 (21.0) | 959/6327 (15.0) | 1.5 (1.01-2.2) | .047 | 1.6 (1.0-2.6) | .03 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Values are expressed as No./total No. (%).

In the 30-day outcome analysis (80% of patients), all-cause mortality was significantly higher in the TXA group (10.4% vs 5.5%; after matching, OR,2.3; 95%CI, 1.2-4.5; P=.01).

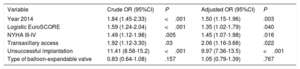

Multivariate analysis of preprocedural and postprocedural variables identified the following independent predictors of in-hospital mortality (table 5): treatment before 2014, logistic EuroSCORE, New York Heart Association functional class III-IV, TXA, and implantation failure.

Predictors of in-hospital mortality

| Variable | Crude OR (95%CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2014 | 1.84 (1.45-2.33) | <.001 | 1.50 (1.15-1.96) | .003 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 1.59 (1.24-2.04) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.02-1.79) | .040 |

| NYHA III-IV | 1.49 (1.12-1.98) | .005 | 1.45 (1.07-1.98) | .016 |

| Transaxillary access | 1.92 (1.12-3.30) | .03 | 2.06 (1.16-3.66) | .022 |

| Unsuccessful implantation | 11.41 (8.58-15.2) | <.001 | 9.97 (7.36-13.5) | <.001 |

| Type of balloon-expandable valve | 0.83 (0.64-1.08) | .157 | 1.05 (0.79-1.39) | .767 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; OR odds ratio.

The main findings of this study are that TXA was associated with higher in-hospital and 30-day mortality than TFA in a propensity score-matched population treated with TAVI; TXA was also associated with higher rates of acute myocardial infarction, general kidney complications, and pacemaker implantation.

Our findings largely have implications for patients deemed candidates for TXA and indicate that TXA should only be considered when TFA is not feasible, not as a general alternative. Indeed, the benefits of TAVI in low- and intermediate-risk patients have only been demonstrated for TFA.1,2,15

There are controversial data on the safety of TXA vs TFA. A meta-analysis of 4504 patients found no differences between the approaches for either events or mortality at 12 months.8 Similarly, a multicenter study of 21 611 patients from the French TAVI registry that used prespecified propensity score matching to compare clinical outcomes between patients treated via TFA (19 995, 92.5%) and those treated via a nonfemoral peripheral access (1616, 7.5%) found no differences in mortality and the only difference in events was a higher rate of major vascular complications in the TFA group.16 The differences could be due to aspects of study design and population makeup. The French study, unlike ours, combined results for TXA and transcarotid access and also had a shorter inclusion period.

The authors of a meta-analysis of 10 528 patients who underwent TAVI via different access routes (TXA, TFA, transaortic, and transapical) reported similar early (in-hospital and 30-day) all-cause mortality rates among patients treated via TXA and TFA. There were, however, differences in mid- and long-term outcomes (at 6 months and 3 years), with higher mortality, infarction, and stroke rates observed in the TXA group. These findings are consistent with ours, as in our series, patients treated with TXA-TAVI showed significantly higher myocardial infarction rates and a tendency toward a higher incidence of stroke. Although we matched all the variables that differed between the 2 populations, including coronary artery disease, and used a statistical test to minimize selection bias, we consider that the groups cannot be matched by PVD, as this is related to access route. Nevertheless, 41% of the patients in the TXA group did not have PVD and could therefore have undergone TAVI via TXA or TFA. Accordingly, our results are not invalidated by severe multicollinearity, although PVD was more common in the TXA group (59% vs 10% in the TFA group). This greater prevalence of PVD among patients treated via TXA may explain the higher mortality rates observed, as PVD has been linked to a higher incidence of death in the setting of TAVI.17 Patients with PVD also have greater atherosclerotic burden, which is the main predictor of risk for cardiovascular disease and death in patients with either obstructive or nonobstructive coronary artery disease.18

Greater atherosclerotic burden might also be associated with the higher rates of kidney complications observed in the TXA group. Atherosclerotic burden in the thoracic aorta has been linked to higher kidney failure rates in patients treated with TAVI, and kidney failure is also a predictor of mortality in this setting.19,20 The amount of contrast medium used to position the valve might also be related to the higher rates of kidney failure observed with TXA, as positioning of the valve through this route can be complicated by the angle between the subclavian artery and the aortic arch, particularly in the horizontal aortas and especially when using a right approach. In addition, most valves used for TXA are self-expanding and their correct placement requires more time and control. This could explain the longer procedures in this group and the greater quantity of contrast medium used.

A higher percentage of patients in the TXA group required pacemaker implantation, supporting findings by Takagi et al.8 in their meta-analysis. We believe that the greater need for pacemakers observed in our study and others21–23 is linked more to the type of valve than the access route used. In our series, a self-expanding valve was used in 85% of TXA-TAVI procedures compared with just 55% of TFA procedures.

There is growing a body of evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of fully percutaneous TXA for TAVI. In a study of 100 consecutive patients treated with percutaneous TXA-TAVI, 85% of the procedures were performed via the left subclavian artery, while 15% were performed via the right subclavian artery.24 Device implantation was successful in 95% of cases and there were no major access site complications. The authors highlighted the presence of a clear learning curve attributable to the greater complexity of the access route. This curve, combined with the low use of TXA in Spain (it is used in just 3.3% of TAVI procedures),25 may have influenced the clinical outcomes in our series.

The percutaneous TXA approach is less invasive than surgery and hence is more comparable to TFA. No studies, however, have directly compared the 2 approaches and as such there is no evidence to support the use of TXA when TFA is feasible.

LimitationsThis was an observational study with a small sample and a short follow-up period. All the patients were from the Spanish TAVI registry. While 100% of high-volume TAVI centers (performing > 100 procedures a year) and 92% of moderate-volume TAVI centers (50-100 procedures a year) participate in the registry, not all hospitals performing TAVI in Spain are represented. Our results may thus be biased by the inclusion of more experienced hospitals. It should also be noted that the registry is not externally audited and not all variables are recorded for all patients, although the vast majority are available for over 90% of patients. The registry does not specify whether TXA was performed via the right or left artery, which may have affected outcomes as right approaches can be more complex. The bleeding and kidney failure figures are reported as total numbers as data on severity or causes were not available. These figures should, therefore, be interpreted with caution. Although biomarkers are used to define infarction, we cannot guarantee that they were systematically measured in all cases. In addition, while we applied methods to minimize selection biases and confounding due to the nonrandomized nature of this study, some bias may remain due to confounding effects not considered. Although we did adjust for known confounding variables, there may have been other less favorable aspects in the group of TXA patients that were not taken into account.

ConclusionsThis is the first study to show that TXA was associated with higher in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates than TFA in a propensity score-matched population treated with TAVI before and after adjustment for potential confounders. Our findings also show that TXA is associated with higher rates of acute myocardial infarction, general kidney complications, and pacemaker implantation.

FundingThe Spanish TAVI registry is managed and maintained with funding from the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Cardiology Society.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSP. Jiménez-Quevedo contributed to conceiving and designing the study; collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data; and writing the article and critically reviewing its content. L. Nombela-Franco, E. Muñoz-García, R. del Valle-Fernández, R. Trillo, J.M. de la Torre Hernández, L. Salido, J. Elizaga, S. Ojeda, J. Sánchez Gila, B. García del Blanco, A. Berenguer, G. Lasa-Larraya, C. Urbano Carrillo, A. Albarrán, R. Ruiz-Salmeron, J. Moreu, L. Gheorghe, D. Arzamendi, G. Yanes-Bowden, J. Diaz, I. Pérez-Moreiras, M. Artaiz, B. Vaquerizo, I. Cruz-Gonzalez, V. Ruiz-Quevedo, R. Blanco-Mata, J.A. Baz, M. Villa, Á. Ortiz de Salazar, V. Tascón-Quevedo, S. Casellas, and R. Moreno contributed to collecting the data and critically reviewing the content of this article.

Conflicts of InterestR. Trillo is a proctor for transcatheter valves for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. R. Moreno is a proctor for Boston, Abbott, Biosensors/NVT and has received speaker and consultancy fees from Edwards, Boston, Abbott, and Medtronic and research fees from Edwards, Abbott, Boston, and Medtronic. L. Nombela-Franco is a proctor for Abbott and has participated in talks for and received speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences. J.M. de la Torre Hernández has received consultancy and presentation fees from Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. I. Cruz-Gonzalez is a proctor for Medtronic. D. Arzamendi is a proctor for Abbott. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- –

There are conflicting data on clinical outcomes in patients treated with TAVI via TXA vs TFA.

- –

Most registries and meta-analyses have not shown any significant differences in mortality between TXA and TFA, although 1 meta-analysis found higher mortality, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke rates for TXA in the mid- and long term.

- –

This study is the first to show higher in-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality rates in a propensity score-matched population treated with TAVI via TXA vs TFA.

- –

The study also shows that TXA is associated with higher rates of acute myocardial infarction, kidney failure, and pacemaker implantation.

We would like to thank Dr. María José Pérez-Vizcayno for her help with reviewing the data and the statistical analysis. We are also very grateful to all the centers and participants in the Spanish TAVI registry.