In recent years, congenital heart disease (CHD) programs for adults have been created in Spain, bringing together 5 well-established centers to address the needs of this growing population.1,2 In our experience, the main need prompting these programs was the cumulative case load of the pediatrics department of the hospital which, starting in the 1980s and personally advanced by a pediatric cardiologist, has become a key facility in our region. In late 2014, a weekly specialized consultation unit was created to care for this population, now in adulthood, offering the following unique characteristics: a) single visit, with the possibility of echocardiography during the visit along with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) or computed tomography (CT) on the same day,3 with the report, results, and next appointment provided at the end of the visit (many patients live in another province) to avoid missing work or school days; b) multidisciplinary approach (pediatrics and cardiology) with 2 pediatricians and 2 cardiologists specifically trained in CHD at national and international hospitals, with at least 1 adult cardiologist and 1 pediatrician present at each visit; c) inclusion in the visits of a pediatric cardiologist from a level 1 Spanish hospital with long-standing experience in the transition from pediatrics, to enhance know-how and smooth transfers of services not available at our hospital, such as heart transplant, percutaneous interventional procedures, or complex surgeries, and d) inclusion, since its inception, of personalized transition for adolescents with CHD from the pediatrics department, starting at age 16 years, and for adults with CHD receiving follow-up from the general cardiology outpatient clinic in our health area and 2 adjacent areas.

The aim of our study was to analyze the clinical characteristics of the various types of CHD seen in the unit.

A clinical descriptive study was undertaken at a tertiary hospital and included all consecutive subjects assessed at the specialized outpatient unit for adult CHDs from October 2014 to December 2019. Data were collected and analyzed on CHD characteristics, including complexity,4 prior procedures (percutaneous or surgical), events (deaths, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations), procedures during follow-up (percutaneous or surgical), and diagnostic tests.

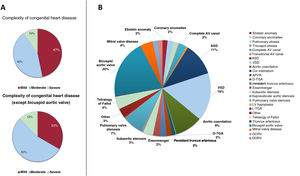

A total of 563 patients were seen in the adult CHD office, 417 (74%) of whom had a “true” CHD. Most (71%) individuals without CHD had been referred for family screening of bicuspid aortic valve. The mean age of patients with CHD was 37±17 years. Among these patients, 47% of CHDs were simple, 43% were moderate, and 10% were highly complex (figure 1).

A, congenital heart diseases assessed, according to complexity. B, specific congenital heart diseases. APVR, anomalous pulmonary venous return; ASD, atrial septal defect; AV canal defect, atrioventricular canal defect; DCRV, double-chambered right ventricle; DORV, double-outlet right ventricle; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

A total of 304 (73%) patients received active follow-up for a median [interquartile range] of 735 [371-1017] days. During this period, there were 6 (2%) deaths, 32 (11%) procedures, and 15 (5%) emergency room visits/hospitalizations. Among the procedures, 2 (0.6%) were heart transplants, 9 (3%) were surgeries at other hospitals, 7 (2.3%) were surgeries at our hospital, 6 (2%) were percutaneous interventions at other hospitals, and 9 (3%) were percutaneous interventions at our hospital (table 1). Median survival was 1080 [656-1435] days.

Clinical characteristics, diagnostic procedures, events, and interventional procedures during follow-up

| Category | Characteristics | Total (N=417) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | Men | 212 (51) |

| Age, y | 37±17 | |

| Complexity | Simple congenital heart disease | 110 (26) |

| Moderate congenital heart disease | 267 (60) | |

| Severe congenital heart disease | 40 (10) | |

| Diagnostic groups | Bicuspid aortic valve | 83 (20) |

| Ventricular septal defect | 67 (16) | |

| Atrial septal defect | 45 (11) | |

| Aortic coarctation | 39 (9) | |

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | 29 (7) | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 18 (4) | |

| Mitral valve disease | 17 (4) | |

| Subaortic stenosis | 15 (3) | |

| Eisenmenger syndrome | 10 (2) | |

| Complete atrioventricular canal | 9 (2) | |

| Persistent truncus arteriosus | 9 (2) | |

| Transposition of the great arteries | 9 (2) | |

| Coronary anomalies | 9 (2) | |

| Ebstein anomaly | 7 (2) | |

| Pulmonary atresia | 7 (2) | |

| Double-outlet right ventricle | 7 (2) | |

| Double-chambered right ventricle | 7 (2) | |

| Anomalous pulmonary venous return | 5 (1) | |

| Transitional AV canal | 3 (1) | |

| Aortic supravalvular stenosis | 3 (1) | |

| Tricuspid atresia | 2 (1) | |

| Transposition of the great arteries, congenitally corrected | 2 (1) | |

| Single ventricle defect | 1 (0) | |

| Truncus arteriosus | 1 (0) | |

| Other | 11 (3) | |

| Surgical history | Previous surgery | 188 (45) |

| Percutaneous | 32 (18) | |

| Surgical | 156 (82) | |

| Additional tests | Electrocardiogram | 405 (97) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | 384 (92) | |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging | 242 (58) | |

| Ergospirometry | 53 (13) | |

| Holter-ECG | 46 (11) | |

| Cardiac computed tomography | 45 (11) | |

| Right catheterization | 33 (8) | |

| Transesophageal echocardiography | 9 (2) | |

| Events during follow-up | Death | 6 (2) |

| Cardiac cause | 2 (1) | |

| Noncardiac cause | 3 (1) | |

| Unknown cause | 1 (0) | |

| Procedures | 32 (11) | |

| Percutaneous | 15 (47) | |

| Surgical | 17 (53) | |

| Emergency room/hospital admissions | 15 (5) |

ECG, electrocardiogram.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Our results reflect our initial experience of providing care for these patients, as well as the health care structure and clinical profile of adult patients with CHD in a tertiary hospital. The clinical practice guidelines underscore the relevance of providing care to these patients at a facility with experience and specifically trained staff. Among our population, 53% had moderate or severe CHD. These patient subgroups benefit the most from specialized care, which raises survival rates compared with care by general cardiology.5 Only 2% of patients in our sample died during follow-up. Individualized discussions in multidisciplinary sessions are essential for each patient and involve pediatric and adult cardiologists, cardiac imaging specialists, interventional cardiologists (catheterization specialists and electrophysiologists), and heart surgeons. A complete personalized assessment of these patients requires considerable human and material resources, in view of the broad heterogeneity of these conditions. Strategies to investigate the anatomy and physiology of the various CHDs have evolved rapidly, with noninvasive techniques (echocardiogram, cMRI, and CT) preferred over invasive studies, as seen in our work (table 1).

Close collaboration between pediatric and adult cardiologists allows adolescents to feel more confident about the medical team, thus ensuring continuity of care. Consequently, patients become more responsible for their own health and acquire greater knowledge of their condition, past or possible future procedures, and implications for work, family, and social life. As this population ages, our approach also helps with new challenges that arise (eg, pregnancy, noncardiac surgery, exercise/rehabilitation, etc). By including a physician from a well-established facility in the unit, the impact of the transition from pediatric to adult care is eased for young patients and their families, and cooperation and relationships are encouraged between pediatric and adult physicians. Last, it has been crucial to facilitate services directly at the center, as well as joint follow-up and the development of educational seminars for patients and relatives to enhance the patient's capacity for autonomy.

The main limitations of this study were its retrospective design and small sample size. However, we describe the structure and initial results of a leading regional hospital in the management of adult CHD that could be applied to other centers with similar characteristics.