The Mediterranean diet is the best evidence-based model for cardiovascular prevention. In addition to 2 major randomized secondary prevention trials (Lyon Heart and CORDIOPREV) and 1 primary prevention trial (PREDIMED) that have demonstrated these benefits, there is an unprecedented body of high-quality prospective epidemiological evidence supporting these beneficial effects. The key elements of this traditional pattern are the abundant use of extra-virgin olive oil and high consumption of foods of natural plant-based origin (fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes) and fish, along with a reduction in processed meats, red meats, and ultraprocessed products. Moderate consumption of wine, preferably red wine, with meals is an essential element of this traditional pattern. Although removing wine consumption from the Mediterranean diet has been associated with a reduction in its preventive efficacy, doubts have recently arisen about the possible adverse effect of even low or moderate intake of any alcoholic beverages. A new large Spanish trial, UNATI, which will begin in June 2024, will randomize 10 000 drinkers aged 50 to 75 years to abstention or moderate consumption. UNATI aims to answer these doubts with the best possible evidence.

Keywords

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), including coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and several other cardiac and vascular conditions, constitutes the leading cause of global mortality and is a major contributor to reduced quality of life.1 Diet has traditionally been considered as a main determinant of cardiovascular health. In fact, one of the 7 cardiovascular health metrics proposed in 2010 by the American Heart Association (“Life's simple 7”) directly corresponds to a healthy diet2 and when, in a Spanish cohort, the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) was included in this score, the Life's Simple 7 metrics was associated with a substantially lower rate of CVD following an inverse linear dose-response pattern.3

In this context, the overall quality of the whole food pattern may be more important and more interpretable than analyses focused on single nutrients or foods. This approach is advantageous because it limits confounding by individual dietary factors, captures the synergistic effects of individual foods and nutrients, and represents the current state of the art in research.4

The MedDiet is characterized by high intake of olive oil, fruit, nuts, vegetables, and cereals; moderate intake of fish and poultry; low intake of dairy products, red meat, processed meats, and sweets; and wine in moderation, consumed with meals.5 The traditional MedDiet should include at least 2 key components: a) a high monounsaturated/saturated fat ratio (because of the use of olive oil as the main or exclusive cooking fat), and b) high intake of unprocessed or minimally-processed plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes. The rationale for this definition is based on recent works,6,7 which emphasized the concept that the cardioprotective effects of the diet appear to be mostly attributable to olive oil, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes. The traditional MedDiet diet is not low in fat but is characterized by a relatively high fat intake, mainly due to monounsaturated fats in the form of olive oil and tree nuts, together with a low intake of saturated fats.5,7,8 In addition, adoption of the MedDiet inevitably requires low consumption (both in quantity and frequency), or even null consumption of processed meats, red meats, sweet desserts, and, particularly strong reductions in the consumption of ultraprocessed foods, rich in added sugars, low-quality fats, and additives.7,9

The individual components of the MedDiet and their constituent bioactive compounds are associated with decreasing cardiovascular disease risk factors,10 including lipoproteins, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.9–18 The MedDiet supplemented with olive oil or nuts reduces the burden of cardiovascular risk factors10–18 and downregulates cellular and humoral inflammatory pathways related to atherosclerosis, with potential benefits on endothelial function as well.19,20 Overall, the protective effects of the MedDiet diet on health outcomes are likely derived from synergistic interactions among different components as a whole dietary pattern rather than from isolated effects of specific food groups.6

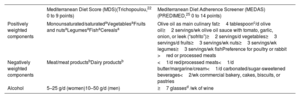

MEDITERRANEAN DIET SCORESSeveral scoring systems have been used to operationally describe the traditional MedDiet.21–25Table 1 shows 2 frequently used scores. Other definitions and scores were less frequently used.

Mediterranean diet scores commonly used in cardiovascular research

| Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS)(Trichopoulou,22 0 to 9 points) | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS)(PREDIMED,25 0 to 14 points) | |

|---|---|---|

| Positively weighted components | Monounsaturated/saturatedaVegetablesaFruits and nutsaLegumesaFishaCerealsa | Olive oil as main culinary fat≥4 tablespoonc/d olive oil≥2 servings/wk olive oil sauce with tomato, garlic, onion, or leek (“sofrito”)≥2 servings/d vegetables≥3 servings/d fruits≥3 servings/wk nuts≥3 servings/wk legumes≥3 servings/wk fishPreference for poultry or rabbit >red or processed meats |

| Negatively weighted components | Meat/meat productsbDairy productsb | <1/d red/processed meats<1/d butter/margarine/cream<1/d carbonated/sugar-sweetened beverages<2/wk commercial bakery, cakes, biscuits, or pastries |

| Alcohol | 5–25 g/d (women)10–50 g/d (men) | ≥7 glassesd /wk of wine |

The 9-item Mediterranean diet score (MDS) was the first published operational score aiming to appraise adherence to the traditional MedDiet and is the most frequently used score.22–25 Assessments using this score have shown beneficial associations with health outcomes in large epidemiological studies and it has been used in a variety of countries, included non-Mediterranean areas. A potential inconvenience of the MDS is that medians are used as cutoffs and they are dependent on sample characteristics, thus compromising between-study comparisons or the generalizability of findings. However, the score is well suited for use in food-frequency questionnaires, because these tools mainly rank participants instead of defining exact intakes.

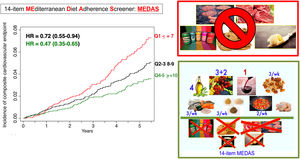

The 14-item Mediterranean diet adherence screenerThe 14-item Mediterranean diet adherence screener (MEDAS) was used in the PREDIMED trial, the largest primary cardiovascular prevention trial with the MedDiet.26–28 The 14-item screener26 uses predefined quantitative goals (number of servings) for the consumption of specific food items and overcomes the potential lack of external comparability that is related to the use of sample-specific medians. This tool allows quick assessment, intervention, and the immediate provision of feedback in intervention studies. The MEDAS-PREDIMED screener has been validated for several populations (such as older adults and persons at high cardiovascular risk), languages, and countries26,29 (figure 1).

Central illustration. Baseline adherence to the Mediterranean diet (14-point PREDIMED score) and incidence of the primary endpoint in the PREDIMED trial (mortality+infarction+stroke+cardiovascular death). MEDAS, Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener; HR, hazard ratio; Q1-Q5, quintile adherence to MEDAS.

The Lyon Heart study30 was the pioneering trial of the MedDiet and CVD. This was a secondary prevention trial aimed at reducing the risk of cardiovascular deaths and recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) in 605 survivors of a previous MI, recruited between 1988 and 1992. Patients were randomized to a Mediterranean-type diet (302 patients) or to a control group (303 patients). In the active intervention group, patients were encouraged to increase their consumption of fruit (no day without fruit), vegetables, bread, and fish. They were also advised to reduce their consumption of red meat (beef, pork, and lamb should be replaced by poultry), and to replace butter and cream by a special margarine, much richer in alpha-linolenic acid, but with less oleic acid than olive oil. Regardless of the fact that the intervention did not exactly correspond to the traditional MedDiet and some other limitations, the Lyon trial showed a significant reduction in major CHD events and deaths, which was maintained over a 4-year follow-up period.

The CORDIOPREV study31 was a single-center, long-term randomized trial conducted in Córdoba (Spain). A total of 1002 patients with established CHD (aged 20-75 years) were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio for 7 years to receive a MedDiet with free provision of extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) or a low-fat diet intervention. The main tool for assessing adherence in the intervention group was the 14-point MEDAS. The primary outcome was a composite of major cardiovascular events, including MI, revascularization procedures, ischemic stroke, peripheral artery disease, and cardiovascular death. The primary endpoint occurred in 198 participants: 87 in the MedDiet group and 111 in the low-fat group. Before a multivariable-adjusted analysis, a significant difference in favor of the MedDiet diet was observed (hazard ratio [HR]=0.753; 95% confidence interval [95%IC], 0.568-0.998).

The results of these trials showed that, in secondary prevention, the MedDiet was indeed superior to the low-fat diet in preventing major cardiovascular events.

Primary preventionThe PREDIMED trial27,28 was the largest trial using the MedDiet. This multicenter primary prevention trial was conducted in Spain and randomized 7447 participants (age range, 55-80 years) initially free of CVD but who were at high cardiovascular risk. Three diets were tested: a MedDiet supplemented with EVOO, a MedDiet supplemented with mixed nuts, and a low-fat control diet (advice to reduce all dietary fat, following the old guidelines of the Step 1 diet of the American Heart Association). Participants received quarterly individual and group educational sessions and, depending on group assignment, free provision of EVOO (1 L/wk), mixed nuts (30g/d), or small nonfood gifts. The composite primary endpoint included MI, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes. A primary endpoint event occurred in 288 participants. The multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios were 0.70 (95%CI, 0.54-0.92) for the group assigned to a MedDiet with EVOO and 0.72 (95%CI, 0.54-0.96) for the group assigned to a MedDiet diet with nuts compared with the control group. No diet-related adverse effects were reported.

PREDIMED is a landmark study, and it remains to date as the best available evidence on diet in CVD prevention. However, a review published in June 2017 identified the PREDIMED trial as having distributions that were significantly different from those expected from randomization.32 Briefly, 425 participants, members of the same household of a previous participant were directly allocated throughout the trial duration to the same group as their previously randomized relative. In addition, 441 individual participants and 26 participant members of the same household from 1 of the 11 recruiting centers were allocated by clusters (clinics) instead of using individual randomization. When this small subset of participants with departures from a purely individual randomization were removed from the analyses, the results were even more favorable for the MedDiet. Furthermore, in a per-protocol (adherence-adjusted) analysis, the hazard ratio for the primary cardiovascular endpoint was 0.42 (95%CI, 0.24-0.63) for the MedDiet compared with the control low-fat diet. The PREDIMED investigators decided to withdraw their original article, and simultaneously republish a new version in the same journal with these new analyses that robustly rejected the isolated criticisms.27,33

Systematic review and meta-analysisHowever, PREDIMED was not an isolated finding in primary cardiovascular prevention. PREDIMED and secondary prevention trials using the MedDiet are only a portion of the large body of evidence indicating the healthfulness of this dietary pattern. Strong evidence supports the use of the traditional MedDiet as a healthy eating pattern for cardiovascular prevention. Many well-conducted and large prospective cohort studies, in addition to randomized trials, have supported these beneficial effects.34 Their results have been pooled in several meta-analyses and systematic reviews, summarised in table 2.

Evidence about Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease

| Author, year | Design (assessed designs) | Outcomes | Pooled results(relative risks*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serra-Majem, 200635 | Trials | CVD | |

| Sofi, 200836 | Cohort studies | CVD mortality | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) |

| Sofi, 201037 | Cohort studies | CVD mortality | 0.90 (0.87-0.93) |

| Tyrovolas, 201038 | Observational studies | CVD incidence or mortality | 0.90 (0.87-0.93) |

| Foroughi, 201339 | Observational studies, trials, reviews, and meta-analyses | Stroke | |

| Psaltopoulou, 201340 | Observational studies | Stroke | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) |

| Rees, 201341 | Trials, primary prevention(the MedDiet definition and selection of studies were incorrect in this meta-analysis) | CVD | |

| Grosso, 201442 | Epidemiological studies | CVD and risk factors | |

| Kontogianni, 201443 | Observational studies and trials | Stroke | 0.68 (0.58-0.79) |

| Martínez-González, 201444 | Cohorts and trials | CVD | RCT 0.64 (0.53-0.79)Observational 0.90 (0.86-0.94) |

| Sofi, 201425 | Prospective studies | CVD incidence or mortality | 0.90 (0.87-0.92) |

| Sleiman, 201545 | Cross-sectional, prospective cohorts, and controlled clinical trials | CVD, CVD mortality, PAD | |

| Huedo-Medina, 201646 | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | CVD outcomes | |

| Liyanage, 201647 | Randomized controlled trials | CVD mortalityCoronary eventsStrokeHF | 0.90 (0.72-1.11)0.65 (0.50-0.85)0.66 (0.48-0.92)0.25 (0.05-1.17) |

| Bloomfield, 201648 | Randomized controlled trials | CVD | |

| Dinu, 201749 | Meta-analyses of observational studies and randomized trials | CVD and health outcomes | |

| Rosato, 201750 | Observational studies | CHD, MIUnspecified strokeIschemic strokeHemorrhagic strokeUnspecified CVD | 0.70 (0.62-0.80)0.73 (0.59-0.91)0.82 (0.73-0.92)1.01 (0.74-1.37)0.81 (0.74-0.88) |

| Martínez-González, 20177 | Clinical trials or prospective cohort studies | CVD incidence or mortality | 0.89 (0.86-0.91) |

| Grosso, 20176 | Prospective studies and randomized controlled trials | CVD incidenceCVD mortalityCHD incidenceMI incidenceStroke incidenceMI (RCT)Stroke (RCT)CVD mortality (RCT)Composite (RCT) | 0.73 (0.66-0.80)0.71 (0.65-0.78)0.72 (0.60-0.86)0.67 (0.54-0.83)0.76 (0.60-0.96)0.60 (0.44-0.82)0.64 (0.47-0.86)0.59 (0.38-0.93)0.55 (0.39-0.76) |

| Galbete, 201851 | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | CVD and chronic diseases | |

| Martínez-Lacoba, 201852 | Reviews and meta-analyses | CVD and other health outcomes | |

| Martínez-González201934 | Systematic reviews, prospective studies, and randomized controlled trials | CVD | |

| Guo-Chong, 201953 | Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | StrokeIschemic strokeHemorrhagic stroke | 0.84 (0.81-0.88)0.86 (0.81-0.91)0.83 (0.74-0.93) |

| Saulle 201954 | Systematic review | Stroke | |

| Rees, 20198 | Randomized controlled trials(the definition of MedDiet was incorrect in this meta-analysis) | CVD | |

| Becerra-Tomás, 202055 | Observational cohorts and randomized controlled trials | CVD (RCT)CVD mortalityCHD incidenceCHD mortalityStroke incidenceStroke mortality | 0.62 (0.50-0.78)0.79 (0.77-0.82)0.73 (0.62-0.86)0.83 (0.75-0.92)0.80 (0.71-0.90)0.87 (0.80-0.96) |

| Tang, 202156 | Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | CVD mortality | 0.91 (0.82-1.01) |

| Finicelli, 202257 | Randomized controlled trials | CVD and health outcomes | |

| Laffond, 202358 | Systematic reviews prospective studies and randomized controlled trials | CVD mortality, CVD |

CHD, nonfatal coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; RCT, randomized controlled trial; PAD, peripheral vascular disease.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarizing large, long-term, observational cohorts and randomized controlled trials providing evidence on the Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease.

It is true that there are methodological weaknesses in some of these meta-analyses.46 In particular, in one of them the definition used for the MedDiet did not correspond to the original concept of the MedDiet, thus making the selection of trials inappropriate.41 This is unfortunately common in systematic reviews in nutritional epidemiology.59–61 Notwithstanding, and beyond these potential limitations in some, but not all, meta-analyses, the evidence demonstrates that there is strong consistency among large randomized trials and long-term and well-conducted observational prospective cohorts supporting the benefits of the MedDiet for CVD prevention. Most cohorts showing this evidence have adequately controlled for confounding, show high retention rates, and are among the best cohorts in terms of their methodological quality. Such strong consistency among high-quality prospective cohorts and large randomized trials with clinical events as the outcome is not available for any other dietary pattern.34

WHAT IS AND WHAT IS NOT THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET?The traditional MedDiet is characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, and whole grain cereals; an abundant fat intake from virgin olive oil, through salads, traditionally cooked vegetables, and legumes; a moderate-to-high consumption of fish and shellfish, and moderate amounts of fermented dairy products. However, it also requires low consumption of meat (particularly processed meats), meat products and ultraprocessed foods. A peculiarity of the MedDiet is the regular consumption of moderate amounts of wine during meals.7

The main sources of fat and alcohol are primarily EVOO and wine, respectively. Low-to-moderate consumption of red wine with meals and a predominance of virgin olive oil as the main culinary fat have been reported to prevent cardiometabolic diseases, including CVD, type-2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity. Current mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of the MedDiet include a reduction in inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, improvements in lipid profile, insulin sensitivity and endothelial function, as well as antiatherosclerotic and antithrombotic properties, mainly attributable to their (poly)phenol content.62,63 The effects of many of these phenolic compounds have been intensely investigated, including hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol, oleocanthal, resveratrol, and many other dietary bioactive phenolic compounds. These compounds have exhibited substantial antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.17,19,62–64

The abundant consumption of fruits and vegetables with a low caloric value but rich in dietary fibre and nutrients allows a greater intake and ensures long-term adherence to this healthy dietary pattern and nutritional adequacy without the need for vitamin supplements. The use of EVOO, as well as many aromatic herbs, increases the palatability of plant-based dishes and facilitates excellent adherence with a very high consumption of fresh and tasty vegetables.

In a globalized world, the current dietary pattern in Mediterranean countries has deviated from former traditional foods and culinary traditions. In this context, some prevalent myths on the MedDiet require clarification. In an informative review, Martínez-González et al.7 exposed 8 typical misconceptions:

- 1.

The traditional MedDiet is not a purely vegetarian diet; it is primarily, but not exclusively, a plant-based diet.

- 2.

The American-style pizza should be considered another type of fast food, but not part of the traditional MedDiet.

- 3.

The main concern regarding alcoholic beverages is not the amount of ethanol intake per se, but rather the pattern of consumption, as explained below.

- 4.

Although there are many reasons to believe eating avocado is healthy, avocado is originally from South America, and it is not a traditional MedDiet food.

- 5.

Other misclassified foods include quinoa, margarine, potatoes, tofu, and potato chips. They do not belong to the traditional MedDiet.

- 6.

Soy is not a traditional Mediterranean food; therefore, a Japo-Mediterranean diet is not a traditional MedDiet.

- 7.

Likewise, an Indo-Mediterranean diet, using other unsaturated fat cooking oils different from olive oil, with similar or higher content in saturated fat than olive oil, does not pertain to the traditional MedDiet.

- 8.

A low-fat MedDiet is not the traditional MedDiet either. The usual amount of fat in the MedDiet is 30% to 45%, but the important factor is not the amount, but the type of fat: olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish should be the main sources of fat, especially EVOO, which may represent 15% or more of the total caloric intake.

Alcohol consumption represents a global health problem and a priority for public health. However, alcohol, especially wine, is a characteristic part of the MedDiet. Well-conducted and analyzed prospective cohort studies have consistently shown that light-to-moderate red wine intake is associated with reduced all-cause mortality and CVD incidence. In fact, the beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors of wine, particularly red wine, are well supported when compared with both abstention and heavy drinking,65–70 especially in men ≥ 50 years and women ≥ 55 years.68 The mechanisms proposed to explain this inverse association with moderate alcohol intake include increases in serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, inhibition of platelet production, activation and aggregation, increased fibrinolysis, beneficial effects on endothelial function and inflammation, and enhanced insulin sensitivity.65,70,71

Furthermore, some aspects of the drinking pattern might act as effect modifiers, including heavy episodic intake (binge drinking), beverage preference, consumption with or without meals and distribution throughout the week.66,67,69 Large cohorts have concluded that ‘healthy’ patterns of moderate drinking reduce CVD, diabetes, and all-cause mortality, particularly in participants 50 to 70 years old.69,72–96

Nonetheless, detrimental effects of alcohol have consistently been found for injury, suicide, several types of cancer, liver disease, mental disorders, and communicable diseases. In addition, observational studies may present some biases (especially misclassification and residual confounding) and the results should be interpreted with caution.97–101

A number of short-term randomized feeding studies, conducted in small numbers of participants, have tested the effects of alcohol on several intermediate mechanisms. They predominantly examined the effects on lipids, oxidation markers, inflammation, and glycemia102 but not on hard clinical endpoints and cannot replace a formal large randomized controlled trial. The longest trial of alcohol to date was the CASCADE trial, which lasted 2 years and included 224 participants with well-controlled type 2 diabetes.103 All participants were initially alcohol-abstainers, and they were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to consume, with dinner, 150mL of mineral water, white wine, or red wine. Participants randomized to initiate red wine increased their HDL-C and apolipoprotein A1 and reduced their number of components of the metabolic syndrome compared with the mineral water group.

In Italy, a randomized controlled trial with 131 patients with MI and diabetes (MedDiet with or without the addition of 4 daily ounces of red wine in a 1:1 ratio) reported higher levels of HDL for red wine, lower levels of oxidation markers, reductions in several inflammatory biomarkers, lower fasting insulin levels, and improved left ventricular function after 1 year.104 Although the MedDiet had beneficial effects on epicardial fat in a large Spanish randomized controlled trial after ablation of atrial fibrillation,105 a recent 6-month randomized controlled trial in Australia with 140 drinkers (consuming approximately 120g/wk of pure alcohol at baseline) concluded that abstinence from alcohol reduced atrial fibrillation recurrences among drinkers with previous atrial fibrillation, who were in sinus rhythm at baseline.106 However, in that Australian trial, more than 25% of participants had a binge drinking pattern at baseline.

The alcohol controversy and the Mediterranean alcohol drinking patternThere are currently 2 completely opposite points of view on alcohol intake in individuals older than 50 years, but they have never been tested face-to-face in a sufficiently large and long-term randomized trial. On the one hand, one point of view holds that complete abstention is the healthiest option for this age group, affirming that “there is no safe level of alcohol intake” for anybody and implying a strong need to reduce average alcohol consumption. On the other hand, a harm reduction strategy can be defended, especially when they exhibit some cardiovascular risk factors, or any disease or condition associated with a higher risk of ischemic CVD, as the last Global Burden of Disease study (GBD20) established in its 2022 report.107 This was also the rationale leading to the recommendation of “moderate” drinking (≤ 7 drinks a week in women and ≤ 14 in men) and avoidance of binge drinking. The GBD did not assess the pattern of alcohol consumption, but only absolute amounts of ethanol intake.

Drinking pattern has been consistently reported to act as an effect modifier for the effect of alcohol on CVD and mortality.66–69,75–79 Specifically, wine consumption, particularly in Mediterranean countries, has been postulated as a key feature of the MedDiet with strong cardioprotective properties, due to the abundance of phenolic compounds (particularly in red wine) with postulated substantial antioxidant and anti-inflammatory beneficial effects.65,79,108–112

This is consistent with the phenomenon known as the “French paradox”, a term coined 3 decades ago to attempt to explain the low rates of heart disease in the French population together with a diet rich in saturated fats.109–119 This paradox was attributed to usual wine consumption with meals. The Greek EPIC cohort reported that none of the other 9 items used to define the MedDiet exerted such a strong benefit as moderate alcohol intake on all-cause mortality. In that cohort, alcohol intake came mainly from wine consumed during meals and the removal of alcohol from the definition of the traditional MedDiet represented a substantial loss of its effectiveness in preventing premature mortality.23 These findings supported the inclusion of a daily glass of wine as one of the 14 goals to be attained in the MedDiet intervention conducted in the PREDIMED trial.26–28 Several studies have found particular benefits of wine regarding life expectancy and CVD prevention.111–122

The controversy regarding alcohol consumption and the lack of evidence based on clinical trials to provide a clear recommendation to the population have prompted the performance of a large new trial, the University of Navarre Alumni Trialists Initiative (UNATI) in Spain. This will be the largest trial ever conducted to assess the health effects of alcohol. UNATI is a large pragmatic noninferiority randomized controlled trial of realistic advice aimed to compare abstention vs moderate wine drinking regarding hard clinical endpoints. Such a trial was long overdue. It will provide first-level evidence to confirm the harms or benefits of one of the most widely used substances by humankind.

The UNATI trial, funded by the European Research Council, and free of any conflicts of interest, has been planned as a 4-year noninferiority randomized controlled trial with more than 10 000 drinkers (men 50-70 years or women 55-75 years consuming ≥ 3 but <40 drinks/wk). To reduce alcohol-associated harms, these drinkers will be randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive 2 different repeated pieces of advice: abstention or moderation. The primary endpoint will be a comprehensive global index outcome, including all-cause mortality, CVD, cancer, other chronic diseases, injuries requiring hospital admission, and major infectious diseases. Moderation is defined as the traditional Mediterranean alcohol drinking pattern (≤ 7 drinks a week in women and ≤ 14 drinks a week in men, avoidance of binge drinking, with preferential consumption of red wine with meals, and consumption spread out throughout the week). Moderate consumption is hypothesized to be noninferior to abstention. The UNATI trial will be conducted in Spain. The randomization and intervention will start in June 2024, with 33 coordinators supervising approximately 500 physicians as trialists. The results of this trial will provide first-level evidence regarding advice on alcohol consumption to individuals in the age range 50 to 75 years.

CONCLUSIONSThe traditional MedDiet is a high-quality dietary pattern. The essential elements of the MedDiet include abundant use of EVOO, high consumption of plant-derived foods (fresh fruits, vegetables, legumes, tree nuts), moderate consumption of fish, whole grain cereals, and red wine (with meals). A large, strong, plausible, and consistent body of prospective evidence and trials is currently available to support the benefits of the MedDiet on cardiovascular health, both in primary and secondary prevention. Alcohol consumption is a controversial issue in the traditional MedDiet. More solid evidence is needed to provide advice on alcohol intake based on sound evidence, without forgetting that alcohol is addictive, and the consumption pattern of alcohol is likely to play an important role as an effect modifier.

FUNDINGThe PREDIMED trial and the SUN cohort were supported by different grants from the official Spanish National Institutes of Health Carlos III (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, ISCIII), CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBEROBN) including several grants from the Fondo de Investigación en Salud (FIS), which is cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund. Partial funding for the SUN cohort was received from the University of Navarre. The UNATI trial is funded by the European Research Council, Project 101097681, with an Advancement Research Grant, 2023-2028. None of the funding sources took part in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEArtificial intelligence has not been used in the development of this review.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSBoth authors have equally contributed to this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.