The population distribution in cardiologists is broader than in other specialties, with significant numbers of young professionals (39% aged ≤ 40 years) and a small percentage close to retirement (12% aged ≥ 60 years),1 a trend likely to persist due to the increased number of positions for cardiology residents (26% added in the past 8 years). The current supply and demand for cardiologists is considered balanced, and no increases in the need for specialists are expected in the next 10 years (some mathematical models project a slight-to-moderate surplus).1 There has also been an increase in temporary (91% of contracts in 2017)1and part-time contracts (particularly in the private sector) and a growing trend toward subspecialization.

Several studies have investigated the employment situation in other countries,2,3 but the situation of young cardiologists specifically in Spain is unknown. Consequently, the Young Cardiologists group of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) carried out an online, self-administered, voluntary and anonymous 40-item survey among SEC members aged ≤ 40 years (with comparisons to avoid any skewing or duplicates) in 2 stages (September 2021 and January-February 2022).

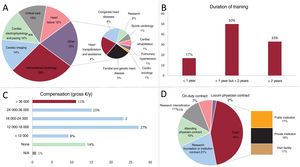

A total of 1124 members were contacted, with responses from 334 (30%) individuals (age, 35.8 ± 4.1 years; 54% women). Further postresidency subspecialty training had been undertaken by 67% (figure 1A), 88% of them in Spain, with fellowships of 1 to 2 years (figure 1B). A total of 86% received financial compensation during the training (figure 1C). Among these, only 11% received wages similar to those established for attending specialists (> €36 000 in gross pay per year), 9% were paid less than the minimum wage (< €12 000 per year; 18% of all men and 28% of all women; P=.08), and 14% received no compensation (10% of all men and 19% of all women; P=.07). Compensation consisted mainly of grants (44%) or contracts from research foundations or institutions (21%) (figure 2D). Among these employees, 64% combined this with other paid work. This was true of 70% of all those earning yearly gross pay lower than €24 000 vs 42.5% of all those earning more; P=.001. Nevertheless, 55% were dissatisfied with the training received (63% of all women vs 46% of all men; P=.013; 58% of those trained in Spain vs 28% of those studying abroad; P=.004). On multivariate analysis, dissatisfaction was associated with low compensation (67% of all those earning yearly gross pay lower than €24 000 vs 15% of all those earning more; P<.0001), with other paid work (65% yes vs 37% no; P<.001), and with the need to postpone a life goal (61% yes vs 35% no; P=.002).

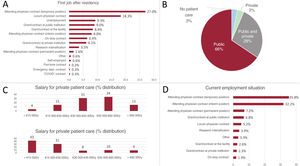

In the early years of their employment, 91% found work upon finishing residency, and temporary contracts were the norm, with only 10% holding an attending position (interim or permanent) (figure 2A). The first contract lasted an average of 7 [interquartile range, 3-15] months (figure 2B). A total of 9% took a median of 1 [1-2] month to find employment. In addition, most contracts (52%) were in the form of grants or research intensification (subsidies aiming to hire physicians to perform the clinical activity of principal investigators), on-duty, or locum physician contracts. Among the people surveyed with work experience ≥ 2 years, 64% reported that they had had a short-term employment contract at some point, 41% had had a locum physician contract, 25% had an on-duty contract, and 37% had been unemployed.

The survey showed that 76% of participants only provided patient care, 14% combined it with research, 4% combined it with teaching duties, and 3% devoted time to all 3. In total, 43% worked in a different location from where they were trained (93% of them in a different autonomous community and 7% in another country). In terms of patient care, 67% worked only in the Spanish National Health System, 4% only in private health, and 29% in both. The most common gross yearly salary was €45 000 to €60 000 in the public sector (34%), <€15 000 in the private sector (43%) (figure 2C), and €45 000 to €60 000 (67%) for those working only in the private sector. A total of 82% reported working on-duty shifts either 3 to 4 times (44%) or 1 to 2 times per month (42%). In terms of contracts, temporary contracts continued to predominate (figure 2D), although a greater percentage held more stable employment (39.4% had interim or permanent positions). While 46% stated that they had taken the competitive examination of the Spanish public employment offer (OPE) system, only 13% had obtained a position within a median of 7 [4-9] years after residency.

Nevertheless, 82% of participants reported job insecurity after residency, 59% defined their current status as unstable, and 73% considered their compensation to be below desirable levels. Additionally, 73% felt the need to postpone a life goal (80% of women vs 66% of men; P=.006), and 62% considered emigrating to improve their conditions (69% of men vs 55% of women; P=.015). The proposals seen as potentially most useful were more frequent competitive examinations (67%), wage increases (66%), the possibility of combining patient care and research (44%), and improved work/life balance (40%).

Despite the possible selection bias, our study shows that most cardiologists decided to subspecialize after residency, often through poorly paid fellowships, and that postresidency contracts tend to be temporary, a situation not limited to the early years. Furthermore, young cardiologists perceive their work situation to be unstable, insecure, and underpaid. For these reasons, we consider that measures should be taken to improve their employment conditions.

FUNDINGNone.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSC. Lozano Granero contributed to the conceptualization, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and wrote the article. E. Díaz-Peláez, A. Barradas-Pires, G. Barge-Caballero, M.T. López-Lluva, and P. Díez-Villanueva made substantial contributions to the conceptualization, design, and drafting of the manuscript and performed a critical review of the intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to accept responsibility for all aspects of the article and to investigate and resolve any question related to the accuracy and veracity of the study.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.