Ventricular tachycardias are an increasingly common ablation target in electrophysiology laboratories, pose major challenges due to the presence of complex substrates, and often require multiple access sites. The epicardial substrate is accessible via percutaneous puncture using the Sosa technique,1 first described more than 20 years ago. In Spain, 14% of ventricular tachycardia ablation procedures are currently performed via an epicardial approach, and it is more frequently used in nonischemic cardiomyopathy (25.3% of cases) than in ischemic (9.2% of cases).2 In the last 2 decades, operators have gained experience and confidence in percutaneous epicardial access, but complications remain, some of which are potentially fatal. Subxiphoid epicardial puncture is performed with an 18-G Tuohy needle (Braun, Kronberg, Germany), an epidural puncture needle with a curved tip that has now become the standard for epicardial access. Epicardial puncture is still a challenge, with a complication rate of 5% to 20%. It is thus only performed in specific centers with experience and on-site surgical facilities. One series reported a 10% rate of severe hemopericardium treated with pericardial drainage.3 In another study of 218 patients managed with the Sosa technique, cardiac tamponade occurred in 8 patients (3.7%), which was resolved with pericardial drainage in 6 patients and with emergent surgery in 2.4 Other complications of epicardial access, rare but very serious, are hepatic puncture with hemoperitoneum, laceration of a vein or coronary artery, or right ventricular (RV)-abdominal fistula.

The needle-in-needle technique has recently been developed for epicardial access using a needle of much smaller caliber and with considerable potential in terms of safety.4 The needle-in-needle technique is based on puncture with a thin needle (21 G) that is supported inside a larger-bore (18 G) needle. Here, we describe our experience with using the needle-in-needle technique to obtain epicardial access.

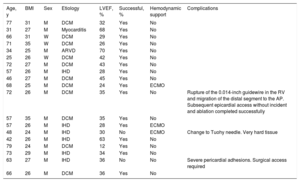

From July 2015 to October 2018, ventricular tachycardia ablation was performed in 19 consecutive patients using the needle-in-needle technique and an epicardial approach.

In this technique, the external 18-G needle is advanced under the xiphoid process. Once the 18-G needle is positioned, the 21-G micropuncture needle is inserted (Mini Access Kit, 21G-L.150mm, Merit; Utah, United States), advanced until the heartbeat is felt, and introduced into the pericardial space. Radiopaque contrast agent is injected to confirm the optimal location and then a 0.018-inch guidewire is advanced (Nitrex, 0.018 in-L.180cm; Minnesota, United States) inside the micropuncture needle. Once its correct location within the pericardial space is verified, the needle is withdrawn, a flexible introducer is advanced, and the 0.018-inch guidewire is exchanged for a 0.032-inch wire, on which a standard 8-Fr introducer can be advanced.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients requiring epicardial access in our center using the needle-in-needle technique. The predominant heart disease was idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (58%). Epicardial access with the needle-in-needle technique was successful in 17 of 19 patients (89%). There were no incidences of hemopericardium, and no patient required pericardial drainage. In 1 patient, the hardness of the diaphragm resisted the passage of such a fine needle, requiring the use of a conventional Tuohy needle. In another patient, significant pericardial adhesions impeded epicardial access and a surgical approach was required. Another patient experienced inadvertent RV puncture, and the 0.018-inch guidewire was advanced into the cavity. When the guidewire was removed, it caught the end of the needle, split into 2 fragments, and caused embolization of the distal fragment. The same micropuncture needle provided access to the epicardium, and the procedure was successfully completed. The next day, the distal fragment of the 0.018-inch guidewire was removed with a loop catheter, without further problems or hemopericardium.

Characteristics of patients managed using needle-in-needle epicardial access

| Age, y | BMI | Sex | Etiology | LVEF, % | Successful, % | Hemodynamic support | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77 | 31 | M | DCM | 32 | Yes | No | |

| 31 | 27 | M | Myocarditis | 68 | Yes | No | |

| 66 | 31 | W | DCM | 29 | Yes | No | |

| 71 | 35 | W | DCM | 26 | Yes | No | |

| 34 | 25 | M | ARVD | 70 | Yes | No | |

| 25 | 26 | W | DCM | 42 | Yes | No | |

| 72 | 27 | M | DCM | 43 | Yes | No | |

| 57 | 26 | M | IHD | 28 | Yes | No | |

| 46 | 27 | M | DCM | 45 | Yes | No | |

| 68 | 25 | M | DCM | 24 | Yes | ECMO | |

| 72 | 26 | M | DCM | 35 | Yes | No | Rupture of the 0.014-inch guidewire in the RV and migration of the distal segment to the AP. Subsequent epicardial access without incident and ablation completed successfully |

| 57 | 35 | M | DCM | 35 | Yes | No | |

| 57 | 26 | M | IHD | 28 | Yes | ECMO | |

| 48 | 24 | M | IHD | 30 | No | ECMO | Change to Tuohy needle. Very hard tissue |

| 42 | 26 | M | IHD | 63 | Yes | No | |

| 79 | 24 | M | DCM | 12 | Yes | No | |

| 73 | 29 | M | IHD | 34 | Yes | No | |

| 63 | 27 | M | IHD | 36 | No | No | Severe pericardial adhesions. Surgical access required |

| 66 | 26 | M | DCM | 36 | Yes | No |

ARVD, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia; BMI, body mass index; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; M, man; PA, pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; W, woman.

In our experience, as well as in the literature, the needle-in-needle technique is the safest way to obtain epicardial access, and no cases have been reported of hemopericardium with tamponade or the need for cardiac surgery.

Kumar et al.5 described the needle-in-needle micropuncture technique for the first time in 2015, comparing their series of 23 patients with a retrospective group of 291 patients managed with the Sosa technique. In the retrospective group, 5 patients (1.7%) required emergent surgery due to severe hemopericardium and 1 died. In contrast, none of the hemopericardia due to the needle-in-needle technique required surgical intervention. In the largest published study, the incidence of severe hemopericardium was significantly higher in the 18-G needle group than in the micropuncture needle group (8.1% vs 0.9%; P <.001), and 42% of these patients with inadvertent RV puncture required cardiac surgery. No patient with inadvertent RV puncture managed using the needle-in-needle technique required surgery.6

Our results show that epicardial access through the needle-in-needle technique can be achieved in a very safe and largely trauma-free way. There were no cases of significant hemopericardium, abdominal bleeding, or RV or epicardial coronary artery damage. This technique provides the operator with increased confidence and helps to reduce the stress associated with pericardial puncture. It may also be useful to improve the safety of conventional pericardiocentesis, particularly in patients with little pericardial effusion, whose risk of RV puncture is higher.