Excess weight promotes the development of several chronic diseases and decreases quality of life. Its prevalence is increasing globally. Our aim was to estimate the trend in excess weight between 1987 and 2014 in Spanish adults, calculate cases of excess weight and its direct extra costs in 2006 and 2016, and project its trend to 2030.

MethodsWe selected 47 articles in a systematic literature search to determine the progression of the prevalence of overweight, nonmorbid obesity, and morbid obesity and average body mass index between 1987 and 2014. We projected the expected number of cases in 2006, 2016, and 2030 and the associated direct extra medical costs.

ResultsBetween 1987 and 2014, the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity increased by 0.28%/y (P=.004), 0.50%/y (P <.001) and 0.030%/y (P=.006) in men, and by 0.10%/y (P=.123), 0.25%/y (P=.078), and 0.042%/y (P=.251) in women. The mean body mass index increased by 0.10 kg/m2/y in men (P <.001) and 0.26 kg/m2/y in women (significantly only between 1987 and 2002, P <.001). We estimated 23 500 000 patients with excess weight in 2016, generating 1.95 billion €/y in direct extra medical costs. If the current trend continues, between 2016 and 2030, there will be 3 100 000 new cases of excess weight, leading to 3.0 billion €/y of direct extra medical costs in 2030.

ConclusionsExcess weight in Spanish adults has risen since the creation of population registries, generating direct extra medical costs that represent 2% of the 2016 health budget. If this trend continues, we expect 16% more cases in 2030 and 58% more direct extra medical costs.

Keywords

Excess weight is a priority concern in public health because it raises mortality (increased 7% to 20%, 45% to 94%, and 176% by overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity, respectively)1 and is the fourth preventable factor that most impairs quality of life.2 The prevalence of excess weight has risen since data were first recorded: in 2014, obesity was present in 10.8% of men and 14.9% of women worldwide, and these figures are expected to jump to 18% and 21%, respectively, by 2025.3

In Spain, excess weight has been analyzed in methodologically heterogeneous population studies, and the trend has only been described in national health surveys, which observed an increase in overweight and obesity of 1.8% and 8.5%, respectively, between 1987 and 2012.4 Likewise, although the individual direct extra medical costs of excess weight are known,5 there is no estimate of the total extra costs for our health system.

This purpose of the study was: a) to determine the trend of excess weight and average body mass index (BMI) in the general Spanish adult population; b) to estimate the prevalence and number of cases of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity in 2006, 2016, and 2030, and c) to estimate total direct extra costs thereof.

METHODSDesignThe study design consisted of a systematic review search and estimate of trends over time.

Search CriteriaWe examined primary literature sources published since 1985 describing the prevalence of excess weight, obesity, or morbid obesity or average BMI (quotient between weight in kg and the square of height in meters) in representative samples of the general Spanish adult population. The study considered overweight to be BMI ≥ 25 and <30, nonmorbid obesity to be BMI ≥ 30 and <40, and morbid obesity to be BMI ≥ 40.

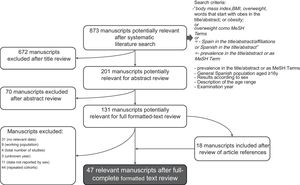

The selection of sources is described in Figure 1. PubMed and Embase were searched for articles that contained body mass index, BMI, overweight, words that started with obes in the title or abstract, or obesity or overweight as MeSH Terms, Spain in the title, abstract, or affiliations or Spanish in the title or abstract, and prevalence in the title, abstract, or as MeSH Term (search performed on 6 March 2017). Only studies including the following were considered: a) general Spanish adult population (≥ 16 years, excluding populations that were only working populations); b) results reported by sex; c) participants’ age range, and d) year of examination. Two of the authors (A. Hernáez and J. Marrugat) reviewed the search titles (n=873) and classified them as relevant or irrelevant. The abstracts of articles with titles classified as relevant by at least 1 author (n=201) were reviewed using the same criterion, and 131 articles were obtained for a full-text review. A review of the literature references cited in these series provided an additional 18 references (n=149). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. When aggregate studies of previous series were identified, the data were collected from the individual studies if possible. When several publications were found for the same study, the publication with more participants or more detailed information was retained.

A total of 47 articles were included in the review. These articles were then used to extract the prevalences of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity as well as average BMI, year of data collection, and whether weight and height data were reported by patients or collected by health professionals. The mean age of participants was also calculated or estimated. The quality of the articles was analyzed, according to whether or not the article expressly defined the following: a) volunteers’ age and location; b) sampling method; c) recruitment response rate reported as ≥ 70%; d) anthropometric information for excluded participants; e) definition of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity; f) exact methodology used to measure weight and height; g) instrumentation used to determine weight and height, and h) measures taken to reduce any observation bias.6 A broader explanation of these aspects is given in the “Determination of Study Quality” section of the .

Statistical AnalysisThe trends of excess weight over time were calculated using multivariate linear regression models: the prevalences of excess weight or average BMI (separated by sex) were the dependent variables, the year of data collection and the mean age of the individuals were the independent variables, and the contribution of each study was weighted according to sample size.7 For each dependent variable, we studied whether or not the use of patient-reported weight and height data in each study (as a categorical variable) significantly affected model behavior. Likewise, we assessed whether or not the inclusion of nonlinear trends reached statistical significance; when this occurred, possible inflection points were estimated by the break point method.8 Previous trends were depicted by weighting each study equally according to sample size (greater size, larger plot point).9 These analyses were performed using R Software (version 3.4.1).10

Prevalences and Cases of Excess Weight in 2006, 2016, and 2030The prevalences of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity in 2006 and 2016 were calculated as described above, and the mean age of the Spanish adult population was estimated for each year from the National Statistics Institute data11 (see “Methods” in the ). For projections up to 2030, 2 scenarios were considered: a) the current trend persists and b) the prevalences of excess weight holds steady at 2016 values.

The cases of excess weight were calculated by applying the previous prevalences to populations of men and women aged ≥ 16 years in 2006 and 2016 and the projections for 2030.12

Approximate Estimate of Total Direct Extra Medical CostsMora et al.5 estimated that direct extra costs due to excess weight in Spain (considering excess costs in these patients due to primary care, specialist, and emergency visits; hospitalizations; laboratory, radiologic, and other types of diagnostic tests; and pharmaceutical prescriptions) were €43.49, €115.13, and €145.64 per year for men and €60.73, €142.95, and €170.07 per year for women with overweight, nonmorbid obesity, and morbid obesity, respectively (compared with persons of normal weight, with the euro value in 2010 taken as a reference).5 The above parameters were adjusted for inflation from 2006 to 2010 (7.91%) and from 2010 to 2016 (5.92%) based on the Consumer Price Index,13 assuming a stable macroeconomic situation with a theoretical annual inflation of 2% from 2016 to 203014 and multiplying by the number of cases previously calculated to estimate the approximate total direct extra costs. A broader explanation of these aspects and the exact values of direct extra costs per person in 2006, 2016, and 2030 is given in the “Methods” section of the and , respectively.

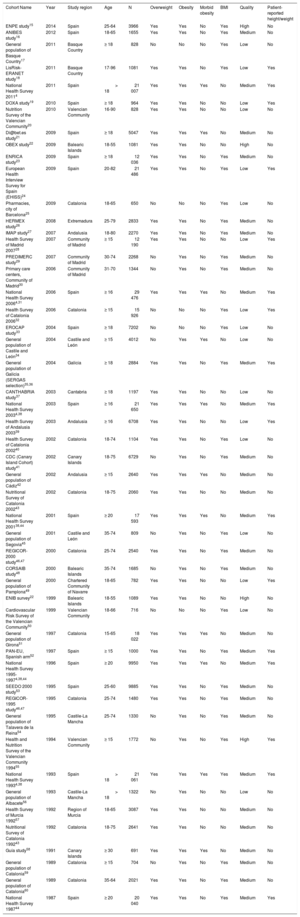

RESULTSThe articles considered provide data from 51 studies conducted between 1987 and 2014 (Table 1),4,15–60 which included 149 955 men and 167 159 women. The prevalences of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity and average BMI appeared in 36, 46, 11, and 29 studies, respectively. The studies were of variable quality (35% were low; 57%, medium; and 8%, high) ().

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review Search

| Cohort Name | Year | Study region | Age | N | Overweight | Obesity | Morbid obesity | BMI | Quality | Patient-reported height/weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENPE study15 | 2014 | Spain | 25-64 | 3966 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High | No |

| ANIBES study16 | 2012 | Spain | 18-65 | 1655 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| General population of Basque Country17 | 2011 | Basque Country | ≥ 18 | 828 | No | No | No | Yes | Low | No |

| LisRisk-ERANET study18 | 2011 | Basque Country | 17-96 | 1081 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Low | Yes |

| National Health Survey 20114 | 2011 | Spain | > 18 | 21 007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| DOXA study19 | 2010 | Spain | ≥ 18 | 964 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | Yes |

| Nutrition Survey of the Valencian Community20 | 2010 | Valencian Community | 16-90 | 828 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | No |

| Di@bet.es study21 | 2009 | Spain | ≥ 18 | 5047 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | No |

| OBEX study22 | 2009 | Balearic Islands | 18-55 | 1081 | Yes | Yes | No | No | High | No |

| ENRICA study23 | 2009 | Spain | ≥ 18 | 12 036 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| European Health Interview Survey for Spain (EHISS)24 | 2009 | Spain | 20-82 | 21 486 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Low | Yes |

| Pharmacies, city of Barcelona25 | 2009 | Catalonia | 18-65 | 650 | No | No | No | Yes | Low | No |

| HERMEX study26 | 2008 | Extremadura | 25-79 | 2833 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| IMAP study27 | 2007 | Andalusia | 18-80 | 2270 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| Health Survey of Madrid 200728 | 2007 | Community of Madrid | ≥ 15 | 12 190 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | Yes |

| PREDIMERC study29 | 2007 | Community of Madrid | 30-74 | 2268 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| Primary care centers, Community of Madrid30 | 2006 | Community of Madrid | 31-70 | 1344 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| National Health Survey 20064,31 | 2006 | Spain | ≥ 16 | 29 476 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| Health Survey of Catalonia 200632 | 2006 | Catalonia | ≥ 15 | 15 926 | No | No | No | Yes | Low | Yes |

| EROCAP study33 | 2004 | Spain | ≥ 18 | 7202 | No | No | No | Yes | Low | No |

| General population of Castile and León34 | 2004 | Castile and León | ≥ 15 | 4012 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Low | No |

| General population of Galicia (SERGAS selection)35,36 | 2004 | Galicia | ≥ 18 | 2884 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | Yes |

| CANTHABRIA study37 | 2003 | Cantabria | ≥ 18 | 1197 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | No |

| National Health Survey 20034,38 | 2003 | Spain | ≥ 16 | 21 650 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| Health Survey of Andalusia 200339 | 2003 | Andalusia | ≥ 16 | 6708 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | Yes |

| Health Survey of Catalonia 200240 | 2002 | Catalonia | 18-74 | 1104 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Low | No |

| CDC (Canary Island Cohort) study41 | 2002 | Canary Islands | 18-75 | 6729 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| General population of Cádiz42 | 2002 | Andalusia | ≥ 15 | 2640 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | No |

| Nutritional Survey of Catalonia 200243 | 2002 | Catalonia | 18-75 | 2060 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Medium | No |

| National Health Survey 200138,44 | 2001 | Spain | ≥ 20 | 17 593 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| General population of Segovia45 | 2001 | Castile and León | 35-74 | 809 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Low | No |

| REGICOR-2000 study46,47 | 2000 | Catalonia | 25-74 | 2540 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| CORSAIB study48 | 2000 | Balearic Islands | 35-74 | 1685 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| General population of Pamplona49 | 2000 | Chartered Community of Navarre | 18-65 | 782 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | Yes |

| ENIB survey22 | 1999 | Balearic Islands | 18-55 | 1089 | Yes | Yes | No | No | High | No |

| Cardiovascular Risk Survey of the Valencian Community50 | 1999 | Valencian Community | 18-66 | 716 | No | No | No | Yes | Low | No |

| General population of Girona51 | 1997 | Catalonia | 15-65 | 18 022 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | No |

| PAN-EU, Spanish arm52 | 1997 | Spain | ≥ 15 | 1000 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | Yes |

| National Health Survey 1995-19974,38,44 | 1996 | Spain | ≥ 20 | 9950 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| SEEDO 2000 study53 | 1995 | Spain | 25-60 | 9885 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| REGICOR-1995 study46,47 | 1995 | Catalonia | 25-74 | 1480 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| General population of Talavera de la Reina54 | 1995 | Castile-La Mancha | 25-74 | 1330 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| Health and Nutrition Survey of the Valencian Community 199455 | 1994 | Valencian Community | ≥ 15 | 1772 | No | Yes | No | Yes | High | Yes |

| National Health Survey 19934,38 | 1993 | Spain | > 18 | 21 061 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium | Yes |

| General population of Albacete56 | 1993 | Castile-La Mancha | > 18 | 1322 | No | Yes | No | No | Low | No |

| Health Survey of Murcia 199257 | 1992 | Region of Murcia | 18-65 | 3087 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Medium | No |

| Nutritional Survey of Catalonia 199243 | 1992 | Catalonia | 18-75 | 2641 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Medium | No |

| Guía study58 | 1991 | Canary Islands | ≥ 30 | 691 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Medium | No |

| General population of Catalonia59 | 1989 | Catalonia | ≥ 15 | 704 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| General population of Catalonia60 | 1989 | Catalonia | 35-64 | 2021 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | No |

| National Health Survey 198744 | 1987 | Spain | ≥ 20 | 20 040 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Medium | Yes |

BMI, body mass index.

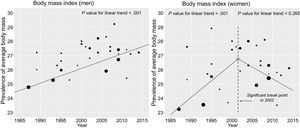

From 1987 to 2014, the prevalences of overweight, total obesity, and morbid obesity increased by+0.28% per year (P=.004),+0.50% per year (P <.001), and+0.030% per year (P=.006) in men and by+0.10% per year (P=.123),+0.25% per year (P=.078), and+0.042% per year (P=.251) in women (Figure 2). None of the above trends exhibited significant nonlinear behavior or break points (P> .05). The equations of these progressions are shown in .

Average BMI values rose linearly between 1987 and 2014 in men (+0.10 per year; P <.001), with no significant break point, and increased between 1987 and 2002 in women (+0.26 per year; P <.001) and did not drop significantly between 2002 and 2014 (–0.14 per year; P=.265) (Figure 3).

There was no difference in the behavior of either trend according to whether weight and height data were reported by patients or were collected by health professionals (P> .05 in all cases).

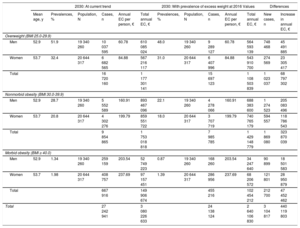

From 2006 and 2016, more than 3.1 million new cases of excess weight appeared (Table 2), which increased direct extra costs of this disease by €524 million per year up to €1.95 billion in 2016, 2% of the health budget (€95.722 billion according to the latest estimate).61

Estimate of Cases of Overweight and Nonmorbid and Morbid Obesity in Spanish Adults and Their Additional Direct Cost (2006, 2016)

| 2006 | 2016 | Differences | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age, y | Prevalences, % | Population, N | Cases, n | Annual EC per person, € | Total annual EC, € | Mean age, y | Prevalences, % | Population, N | Cases, n | Annual EC per person, € | Total annual EC, € | New Cases, n | Increase in Annual EC, € | |

| 2006 | 2016 | 2006-2016 | ||||||||||||

| Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) | ||||||||||||||

| Men | 45.2 | 45.3 | 18 214 203 | 8 243 748 | 40.05 | 330 162 107 | 48.4 | 48.0 | 18 957 273 | 9 105 178 | 46.06 | 419 384 499 | 861 430 | 89 222 392 |

| Women | 46.5 | 30.1 | 19 022 087 | 5 723 746 | 55.93 | 320 129 114 | 49.5 | 31.0 | 20 023 208 | 6 215 204 | 64.33 | 399 824 073 | 491 458 | 79 694 959 |

| Total | 13 967 494 | 650 291 221 | 15 320 382 | 819 208 572 | 1 352 888 | 168 917 351 | ||||||||

| Nonmorbid obesity (BMI 30.0-39.9) | ||||||||||||||

| Men | 45.2 | 17.4 | 18 214 203 | 3 171 093 | 106.02 | 336 199 280 | 48.4 | 22.1 | 18 957 273 | 4 193 349 | 121.95 | 511 378 911 | 1 022 256 | 175 179 631 |

| Women | 46.5 | 15.9 | 19 022 087 | 3 020 707 | 131.64 | 397 645 869 | 49.5 | 18.0 | 20 023 208 | 3 596 168 | 151.41 | 544 495 797 | 575 461 | 146 849 928 |

| Total | 6 191 800 | 733 845 149 | 7 789 517 | 1 055 874 708 | 1 597 717 | 322 029 559 | ||||||||

| Morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0) | ||||||||||||||

| Men | 45.2 | 0.53 | 18 214 203 | 96 535 | 134.12 | 12 947 274 | 48.4 | 0.87 | 18 957 273 | 164 928 | 154.26 | 25 441 793 | 68 393 | 12 494 519 |

| Women | 46.5 | 0.98 | 19 022 087 | 186 416 | 156.62 | 29 196 474 | 49.5 | 1.39 | 20 023 208 | 278 323 | 180.14 | 50 137 105 | 91 907 | 20 940 631 |

| Total | 282 951 | 42 143 748 | 443 251 | 75 578 898 | 160 300 | 33 435 150 | ||||||||

| Total | 20 442 245 | 1 426 280 118 | 23 553 150 | 1 950 662 178 | 3 110 905 | 524 382 060 | ||||||||

BMI, body mass index; EC, extra cost.

If the current trend persists, in 2030 there will be about 27.2 million adults with excess weight, with direct extra costs of about €3.08 billion per year (Table 3). This would be approximately an additional 3.1 million cases (and additional €440 million per year of extra costs) compared with the scenario in which the disease stabilizes at 2016 values. Assuming a linear increase, cumulative extra costs between 2016 and 2030 in the worst case scenario would rise to €3.081 billion.

Estimate of Cases of Overweight and Nonmorbid and Morbid Obesity in Spanish Adults in 2030 and Their Additional Direct Cost if Excess Weight Progresses at Current Rates or Holds Steady at 2016 Levels

| 2030: At current trend | 2030: With prevalence of excess weight at 2016 Values | Differences | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | Prevalences, % | Population, N | Cases, n | Annual EC per person, € | Total annual EC, € | Prevalences, % | Population, N | Cases, n | Annual EC per person, € | Total annual EC, € | New cases, n | Increase in annual EC, € | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) | |||||||||||||

| Men | 52.9 | 51.9 | 19 340 260 | 10 037 595 | 60.78 | 610 085 024 | 48.0 | 19 340 260 | 9 289 127 | 60.78 | 564 593 139 | 748 468 | 45 491 885 |

| Women | 53.7 | 32.4 | 20 644 317 | 6 682 565 | 84.88 | 567 216 117 | 31.0 | 20 644 317 | 6 407 996 | 84.88 | 543 910 700 | 274 569 | 23 305 417 |

| Total | 16 720 160 | 1 177 301 141 | 15 697 123 | 1 108 503 839 | 1 023 037 | 68 797 302 | |||||||

| Nonmorbid obesity (BMI 30.0-39.9) | |||||||||||||

| Men | 52.9 | 28.7 | 19 340 260 | 5 552 589 | 160.91 | 893 467 096 | 22.1 | 19 340 260 | 4 278 066 | 160.91 | 688 383 600 | 1 274 523 | 205 083 496 |

| Women | 53.7 | 20.8 | 20 644 317 | 4 302 276 | 199.79 | 859 551 722 | 18.0 | 20 644 317 | 3 707 719 | 199.79 | 740 765 179 | 594 557 | 118 786 543 |

| Total | 9 854 865 | 1 753 018 818 | 7 985 785 | 1 429 148 779 | 1 869 080 | 323 870 039 | |||||||

| Morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0) | |||||||||||||

| Men | 52.9 | 1.34 | 19 340 260 | 259 159 | 203.54 | 52 749 223 | 0.87 | 19 340 260 | 168 260 | 203.54 | 34 247 640 | 90 899 | 18 501 583 |

| Women | 53.7 | 1.98 | 20 644 317 | 408 757 | 237.69 | 97 157 451 | 1.39 | 20 644 317 | 286 956 | 237.69 | 68 206 572 | 121 801 | 28 950 879 |

| Total | 667 916 | 149 906 674 | 455 216 | 102 454 212 | 212 700 | 47 452 462 | |||||||

| Total | 27 242 941 | 3 080 226 633 | 24 138 124 | 2 640 106 830 | 3 104 817 | 440 119 803 | |||||||

BMI, body mass index; EC, extra costs.

Excess weight is increasingly prevalent among Spanish adults: the data collected indicate that overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity rose significantly in men between 1987 and 2014, whereas obesity increased only slightly in women. The average BMI increased linearly and significantly in men over this period and in women only until 2002. These data are consistent with the rise in overweight and obesity of 1.8% and 8.5% described in national health surveys between 1987 and 2012,4 although they differ from the pattern of BMI increase reported by other studies.3 Possible explanations for this weight gain are that, during the study period, the Spanish population: a) acquired less healthy dietary patterns (higher intake of cookies, industrial pastries, dairy desserts, juice, and soft drinks); reduced their fruit intake at home; and dramatically increased eating out62; b) continued to follow a moderately sedentary lifestyle,63 or c) experienced an increase in employment levels, working hours, and purchasing power (particularly before the financial recession that began in 2009), which would have encouraged less traditional dietary standards or more sedentary lifestyles.64

Excess weight leads to considerably higher direct extra medical costs because these patients use health care more often (mainly due to more primary care, specialist, and emergency medical visits; more hospitalizations; more laboratory, radiologic, and diagnostic tests, and more drug prescriptions), both due to the excess weight itself and due to its multiple associated comorbidities.5,65 According to our estimates, these direct extra medical costs were approximately €1.95 billion in 2016 (2% of the annual health budget), consistent with those described for other health systems (0.7%-2.8%).66 Because direct medical expenses account for about half the total extra cost of obesity in other European systems (which also consider higher costs due to possible sick leave, loss of productivity and performance, the cost of time invested by other health system workers, etc),67 the total extra cost due to excess weight could be around €3.9 billion for 2016. It was estimated that these were approximately €2.5 billion by the late 1990s65 and, therefore, a cost increase of €1.4 billion per year within the next 15 to 20 years is plausible.

The growing prevalence of excess weight could rapidly become unsustainable. If the current trend continues, in 2030 there will be 27.2 million cases of excess weight (3.1 million more cases than if the trend remains steady at 2016 values). This progression could be tackled by multilevel interventions (applying taxes to unhealthy foods, promoting settings that discourage weight gain, implementing educational policies that enhance healthy lifestyles, and organizing better prevention systems),68 such as has been undertaken in North Karelia, Finland.69 New pharmacological strategies (eg, bupropion-naltrexone, liraglutide) could also be useful.70 Apart from the health benefit, maintaining the prevalence of excess weight at current levels (already sufficiently high) would save about €3.0 billion by 2030. Considering that obesity prevention plans in Spain (such as the NAOS Strategy71) did not involve investments of such magnitude, these programs could be financially cost-effective in the short- to mid-term.

Limitations and StrengthsOur review search has several limitations. First, it included studies of uneven methodological quality conducted in 3 different decades. This heterogeneity was partially corrected by using multivariate linear regression models and by weighting the studies according to sample size. Second, the review maximized the number of time points by including studies that enrolled participants aged 15 to 17 years4,18,20,28,31,32,34,38,39,42,51,52,55,59; because these studies did not describe the use of other cutoff points or standards to quantify excess weight in this population, it was deduced that the studies used the same ones as for the adult population, which is not an ideal method. Third, excess weight did not increase significantly in women, probably due to greater dispersion in female prevalences. Fourth, an estimate of the mean age of Spanish adults was used to calculate the prevalences of excess weight because the National Institute of Statistics does not provide this information. Last, total extra cost due to this disease (considering all direct and indirect costs) could not be calculated, and only approximate direct extra medical costs could be estimated because there are no estimates of this parameter in the Spanish health system.

This study has several strengths. This is the first systematic literature search on excess weight trends conducted with all epidemiologic studies among the general Spanish adult population. In addition, it estimates the number of individuals who currently carry excess weight and then provides projections for 2030. Last, it contextualizes the social relevance of the problem by providing estimated figures of current and future direct extra costs.

CONCLUSIONSThe prevalences of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity have risen since records were first kept in Spain, although the incremental rise among women is not statistically significant. The result is a prevalence of more than 23 million persons with excess weight, with direct extra medical costs of almost 2% of the 2016 health budget. According to this trend, by 2030 there will be about 3.1 million new cases and extra costs of about €3.0 billion per year (more than 3% of the current health budget). Stabilizing excess weight at 2016 levels, which are already alarming, would save almost €3.0 billion by 2030.

FUNDINGThis study was funded by AGAUR (University and Research Aid Management Agency) (2014-SGR-240), the Health Department of the Generalitat de Catalunya (SLT006/17/00029), the Carlos III Health Institute (CES12/025, CD17/00122), CIBEROBN (Biomedical Research Center for the Obesity and Nutrition Pathophysiology Network), CIBERCV (Biomedical Research Center for the Cardiovascular Disease Network), and the European Regional Development Fund, as well as Novo Nordisk, which provided an unconditional grant.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Excess weight is one of the factors most likely to increase the morbidity and mortality of chronic diseases, most likely to impair quality of life, and most likely to raise health costs.

- –

The prevalence of excess weight has risen worldwide since the start of record-keeping.

- –

The prevalences of overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity in Spain increased 0.28% per year (P=.004), 0.50% per year (P <.001), and 0.030% per year (P=.006) in men and 0.10% per year (P=.123), 0.25% per year (P=.078), and 0.042% per year (P=.251) in women, respectively.

- –

In 2016, there were 23.5 million cases of excess weight, leading to direct extra costs of €1.95 billion per year (2% of the health budget for 2016).

- –

Stabilizing the prevalence of excess weight at 2016 levels would prevent 3.1 million new cases and save €3.0 billion in cumulative direct extra costs by 2030.

We appreciate the collaboration of Dr. Francisco Poyato (Novo Nordisk Pharma Spain, Madrid) in the discussion of the results of this work.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2018.10.010.