Heart failure (HF) is a social and health care challenge, due to its high prevalence and poor prognosis.1,2 In the case of patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), the prognosis may improve with the use of devices, such as an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICDs) or cardiac resynchronization therapy. Cardiac resynchronization therapy also alleviates the symptoms of patients with QRS >130ms, but these individuals only account for 30% of this population.3 Therefore, new treatments are welcome, particularly when the QRS is narrow.

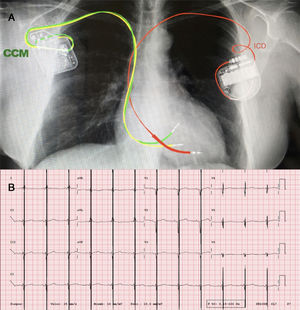

Cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) consists of delivering biphasic high-voltage signals (7.5V/22ms) to the interventricular septum during absolute refractory periods. The therapy is administered for several hours a day, using a device which, in its latest model, the Optimizer Smart IPG (Impulse Dynamics, United States), is fitted with 2 conventional pacemaker leads and is recharged wirelessly every week (figure 1). Implantation is similar to pacemaker placement and only requires local anesthesia. In cells, the device optimizes calcium handling by phospholamban phosphorylation and SERCA-2 upregulation, among others, thereby inducing reversal of the fetal myocyte gene program and favorable myocardial remodeling.4 This effect occurs in the acute stage as well as in the long-term and not only in the area of energy release, but also over the entire myocardium. Several clinical trials support the benefits of this device; in fact, the latest trial, FIX-HF-5C, showed that CCM therapy improves exercise tolerance at 6 months (increase in peak oxygen consumption similar to that seen with cardiac resynchronization therapy, although population differences should be taken into account), quality of life, and a composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalizations.5 Consequently, the European Society of Cardiology considers CCM to be a potential therapy for patients with HF (LVEF 25%-45%) and QRS <130ms.6

A: posteroanterior thoracic radiograph, showing the ICD generator at the top left, with its leads in the right ventricular apex, and the CCM generator at the top right, with its leads inserted in the interventricular septum. B: electrocardiogram showing the CCM therapy artifact in the middle of the QRS (intermittent treatment not seen in some electrocardiograms).

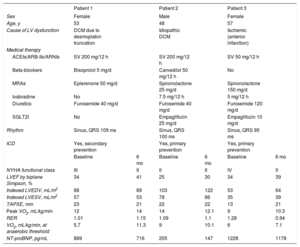

We describe the first 3 cases in Spain of patients with HF and reduced LVEF who were symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy, who had no indication for heart transplant, and who underwent CCM implantation as a result (table 1).

Baseline characteristics and clinical progress of the 3 patients who received CCM therapy

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Age, y | 53 | 48 | 57 | |||

| Cause of LV dysfunction | DCM due to desmoplakin truncation | Idiopathic DCM | Ischemic (anterior infarction) | |||

| Medical therapy | ||||||

| ACEIs/ARB-IIs/ARNIs | SV 200 mg/12 h | SV 200 mg/12 h | SV 50 mg/12 h | |||

| Beta-blockers | Bisoprolol 5 mg/d | Carvedilol 50 mg/12 h | No | |||

| MRAs | Eplerenone 50 mg/d | Spironolactone 25 mg/d | Spironolactone 150 mg/d | |||

| Ivabradine | No | 7.5 mg/12 h | 5 mg/12 h | |||

| Diuretics | Furosemide 40 mg/d | Furosemide 40 mg/d | Furosemide 120 mg/d | |||

| SGLT2I | No | Empaglifozin 25 mg/d | Empaglifozin 10 mg/d | |||

| Rhythm | Sinus, QRS 109 ms | Sinus, QRS 100 ms | Sinus, QRS 95 ms | |||

| ICD | Yes, secondary prevention | Yes, primary prevention | Yes, primary prevention | |||

| Baseline | 6 mo | Baseline | 6 mo | Baseline | 6 mo | |

| NYHA functional class | III | II | II | II | IV | II |

| LVEF by biplane Simpson, % | 34 | 41 | 25 | 30 | 34 | 39 |

| Indexed LVEDV, mL/m2 | 88 | 89 | 103 | 122 | 53 | 64 |

| Indexed LVESV, mL/m2 | 57 | 53 | 78 | 86 | 35 | 39 |

| TAPSE, mm | 23 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 13 | 21 |

| Peak VO2, mL/kg/min | 12 | 14 | 14 | 12.1 | 9 | 10.3 |

| RER | 1.01 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.1 | 1.28 | 0.94 |

| VO2, mL/kg/min, at anaerobic threshold | 5.7 | 11.3 | 9 | 10.1 | 6 | 7.1 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 889 | 716 | 205 | 147 | 1228 | 1178 |

ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ARNIs, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; CCM, cardiac contractility modulator; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV, left ventricle; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRAs, mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors; SV, sacubitril-valsartan; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; VO2, oxygen consumption.

The first patient was a 53-year-old woman with dilated cardiomyopathy, ICD implantation after aborted sudden cardiac death, and considerable limitations in her daily activities despite therapy. Therefore, a CCM device was implanted with no incidents. In the first few weeks, she exhibited a transient increase in the impedance of the CCM leads, probably related to inflammation in the insertion area in the myocardium, but that did not prevent device charging or proper application of the therapy.

The second patient was a 48-year-old man with dilated cardiomyopathy and severe systolic dysfunction. An ICD and a CCM were simultaneously implanted with no complications. At 3 months, the patient experienced an appropriate ICD discharge due to ventricular fibrillation, which did not affect CCM functioning. This patient and the first one both had Medtronic ICDs with lead integrity alert algorithms, and during follow-up had occasional high-impedance measurements at the tip-coil dipole and detection of short V-V intervals which, after technical analysis by the 2 companies, were interpreted as episodic interference between the CCM and the ICD, with no repercussions on the functioning of either device.

The third patient was a 57-year-old woman with ischemic heart disease and severely reduced LVEF who had an ICD and a mechanical mitral valve. She progressed to dyspnea on minimal exertion. The CCM device was implanted with no incidents but, as in the first patient, it initially displayed a CCM device alarm due to increased impedance in the leads.

At 6 months (table 1), 2 patients had improved clinically, all 3 showed slight LVEF improvement, and peak oxygen consumption had improved in 2 but had worsened in the other. Additionally, oxygen consumption at the anaerobic threshold (considered the parameter least modifiable by motivation and training) had increased in all 3 patients, and although there were a slight decrease in the N-terminal fraction of probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), it did not appear to be clinically significant. There were no changes in neurohormonal or diuretic medical treatments.

Therefore, our initial experience with CCM has been positive. The treatment has been demonstrated to be effective, as well as safe until this point in follow-up. In HF, these devices are known to have a placebo effect. However, the improvement observed in peak oxygen consumption at the anaerobic threshold suggests a beneficial therapeutic effect. Our patients experienced no device complications or relevant interferences with the ICD, other than the lead integrity alerts described.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. de Juan Bagudá, J.F. Delgado Jiménez, and F. Arribas Ynsaurriaga have participated as speakers at lectures sponsored by Impulse Dynamics. The Cardiology Department of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre is participating in a clinical trial funded by Impulse Dynamics.