Heart failure (HF) is prevalent in advanced ages. Our objective was to assess the impact of frailty on 1-year mortality in older patients with ambulatory HF.

MethodsOur data come from the FRAGIC study (Spanish acronym for “Study of the impact of frailty and other geriatric syndromes on the clinical management and prognosis of elderly outpatients with heart failure”), a multicenter prospective registry conducted in 16 Spanish hospitals including outpatients ≥ 75 years with HF followed up by cardiology services in Spain.

ResultsWe included 499 patients with a mean age of 81.4±4.3 years, of whom 193 (38%) were women. A total of 268 (54%) had left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, and 84.6% was in NYHA II functional class. The FRAIL scale identified 244 (49%) pre-frail and 111 (22%) frail patients. Frail patients were significantly older, were more frequently female (both, P <.001), and had higher comorbidity according to the Charlson index (P=.017) and a higher prevalence of geriatric syndromes (P <.001). During a median follow-up of 371 [361-387] days, 58 patients (11.6%) died. On multivariate analysis (Cox regression model), frailty detected with the FRAIL scale was marginally associated with mortality (HR=2.35; 95%CI, 0.96-5.71; P=.059), while frailty identified by the visual mobility scale was an independent predictor of mortality (HR=2.26; 95%CI, 1.16-4.38; P=.015); this association was maintained after adjustment for confounding variables (HR=2.13; 95%CI, 1.08-4.20; P=.02).

ConclusionsIn elderly outpatients with HF, frailty is independently associated with mortality at 1 year of follow-up. It is essential to identify frailty as part of the comprehensive approach to elderly patients with HF.

Keywords

Heart failure (HF) is a global public health problem associated with high morbidity and mortality, and significant resource utilizatiaon.1 The incidence of HF increases with age,2 it affects up to 20% of the population aged at least 75 years,3 and it is the leading cause of hospitalization in this age group in developed countries.4,5 Prognosis has improved in recent years due to a better understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and an improved therapeutic approach.6 Current recommendations emphasize the relevance of providing individualized strategies and treatments and taking into account the clinical situation and comorbidities of each patient.7 However, older patients are usually underrepresented or even excluded from large clinical trials.3 In addition, conditions that are prevalent in older patients with HF, such as frailty, are not assessed in routine clinical practice, despite their marked prognostic impact and even though their identification would allow individualized plans to be tailored to each patient.8-10 In our setting, the prevalence of frailty has been studied in patients admitted for acute HF who, in general, have been attended in geriatrics or internal medicine services. Our study is novel, in that it assessed the presence and prognosis of frailty in older patients with ambulatory HF, who had been exclusively followed up by cardiology services in Spain. Our aim was to assess the impact of frailty on 1-year all-cause mortality in these patients. We also studied its influence on hospital admission rates during follow-up.

METHODSStudy design and populationThe”Impact of frailty and other geriatric syndromes on the clinical management and prognosis of the elderly outpatient with heart failure” (FRAGIC) study was an observational, prospective, multicenter registry11 promoted by the Geriatric Cardiology Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. This study was approved by the Hospital de la Princesa Drug Research Ethics Committee, which acted as the coordinating center. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged at least 75 years with a diagnosis of HF according to the recommendations and guidelines in force at the time of inclusion,12 under outpatient follow-up by the cardiology services of 16 Spanish hospitals, without admissions for HF in the month prior to inclusion, and who gave informed consent. All consecutive patients who met the inclusion criteria in the period March 2019 to September 2019 were included. Data were prospectively collected in HF consultations or in the HF day hospital by medical and nursing research staff trained in geriatric assessment.

Geriatric assessments were conducted during the first visit by interviewing patients, family members, or caregivers. The following aspects were assessed:

- •

Functional capacity for basic activities of daily living using the Barthel index (dependence if ≤ 60 points).13,14

- •

Functional capacity for instrumental activities using the Lawton-Brody index (total independence if 8 points).15

- •

Cognitive status assessed using the Pfeiffer test (cognitive impairment if ≥ 3 points).16

- •

The physical performance test using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).17 A score of less than 10 identifies patients with physical frailty.

- •

Frailty was assessed using several scales:

- –

FRAIL scale: frailty was defined by a score of at least 3 and prefrailty was defined as a score of 1 to 2.18

- –

Self-reported questions by frailty phenotype (using an adaptation of Fried's criteria): frailty was defined by a score of at least 3.19

- –

Clinical Frailty Scale: frailty was defined by a score of at least 4.20

- –

Visual Mobility Scale: frailty was defined by a score of at least 2 on a visual mobility scale (based on the work of Martínez-Sánchez et al.5).

- •

Comorbidity was assessed using the Charlson index.21

- •

Number of drugs prescribed for lifetime use.

- •

Nutritional risk assessment assessed using the Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF). Normal nutritional status was defined by a score of at least 12.22

- •

Depression screening using the Yesavage test. Depression was diagnosed by a score of at least 5 on this 15-item scale.23

- •

Quality of life was analyzed using a visual analog scale with scores from 0 to 10. Lower values indicate worse quality of life. In addition, a self-reported scale from 1 to 5 was applied (1, poor; 2, acceptable; 3, good; 4, very good; and 5, excellent).

Detailed information on the frailty scales used is provided in the supplementary data.

Functional status was assessed using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) scale. To detect events, the researchers conducted clinical follow-up, independently of standard clinical follow-up, via face-to-face visits, reviews of medical records, or telephone contact with patients or family members at least every 2 years. We collected data on total mortality and the need for urgent all-cause hospitalization (duration> 24hours).

Ethical aspectsInclusion in the FRAGIC study did not involve changes to the patients’ clinical treatment, which was conducted according to standard clinical practice and the recommendations of current clinical practice guidelines.12 The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Hospital de la Princesa Drug Research Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed as percentages and continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation. Univariate comparison between each independent variable and the FRAIL scale, which was used as a reference because of its simplicity and reproducibility, was assessed using ANOVA or the Kruskall-Wallis test, as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain data on disease-specific survival, the cumulative incidence of any-cause admission, and mortality. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The predictive model was constructed using a sequential procedure. Firstly, using the results obtained from the log-rank test, we selected the variables that were significantly different (P <.001). Due to the large number of variables and comparisons, this cutoff was used to avoid type I errors (ie, obtaining false positives). Next, a predictive model was fitted using Cox regression (multivariate analysis). A Cox regression was performed for each of the different frailty scales to avoid collinearity between them: in each case, the significant variables were included in the log-rank test and the corresponding frailty scale. These models were adjusted for the following confounding variables: age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), number of admissions in the previous year, systolic blood pressure, glomerular filtration rate, treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARA II), beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and diuretics, and by the Charlson comorbidity index. These adjustments were also made taking into account collinearity. Data were analyzed using our own codes and the base functions in R version 4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

RESULTSA total of 499 patients were included. Median age was 81.4±4.3 years and 38% were women. Prior to inclusion, the median time since diagnosis of HF was 25 [12-60] months. Most patients (85%) were in NYHA class II (only 0.2% were in NYHA class III-IV). Mean LVEF was 43% and just over half of the patients (54%) had an LVEF of less than 40% (in the of the supplementary data shows the subanalysis of the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the registry by LVEF category). The main cause of HF was ischemic heart disease (48%). The FRAIL scale identified 22% of patients as frail and 49% of patients as prefrail. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the patients by frailty. Frail and prefrail patients were more frequently women and had a higher mean age; the frailer patients had significantly more comorbidity and geriatric syndromes. Frail patients had significantly worse functional status, more congestion on physical examination, and higher LVEF and N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) values. Frail patients also underwent more admissions for HF in the previous year.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to the degree of frailty on the FRAIL scale

| Characteristics | Total (n=499) | Robust(n=144, 29%) | Prefrail(n=244, 49%) | Frail(n=111, 22%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age, y | 81.4±4.3 | 80.2±3.69 | 81.4±4.35 | 82.9±4.51 | <.001 |

| Men | 307 (61.7) | 111 (77.1) | 150 (61.5) | 47 (42.3) | <.001 |

| BMI | 27.6±4.6 | 27.3±4.38 | 27.3±4.53 | 28.6±5.10 | .029 |

| Hypertension | 400 (80.3) | 106 (73.6) | 196 (80.7) | 98 (88.3) | .014 |

| Diabetes | 199 (40) | 57 (39.6) | 91 (37.3) | 51 (46.4) | .271 |

| Dyslipidemia | 334 (67.3) | 98 (68.5) | 167 (69.0) | 69 (62.2) | .417 |

| COPD | 59 (14.8) | 15 (10.4) | 41 (16.8) | 18 (16.2) | .208 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 157 (31.5) | 42 (29.4) | 78 (32.0) | 37 (33.3) | .780 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 263 (52.7) | 71 (49.3) | 130 (53.3) | 62 (55.9) | .565 |

| LVEF, % | 42.7±13.9 | 40.7±13.6 | 42.1±13.5 | 46.5±14.5 | .003 |

| LVEF ≤ 40% | 268 (53.7) | 89 (61.1) | 132 (54.3) | 47 (42.3) | .003 |

| LVEF 41%-49% | 78 (15.6) | 21 (14.6) | 39 (16) | 18 (16.2) | .003 |

| LVEF ≥ 50%. | 153 (30.6) | 35 (24.3) | 72 (29.6) | 46 (41.4) | .003 |

| Ischemic etiology | 48.2 | 49 (45) | 79 (48.5) | 33 (53.2) | .860 |

| Duration of HF, mo | 25 [12-60] | 36 [12.5-77.5] | 24 [12-57] | 24 [9-60] | .081 |

| Number of admissions for HF in the previous year | 0 [0-1] | 0 [0-1] | 0 [0-1] | 1 [0-1] | <.001 |

| NYHA II | 422 (84.6) | 105 (72.9) | 215 (88.1) | 102 (91.9) | <.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 55 (11) | 16 (11.1) | 26 (10.7) | 13 (11.8/) | .949 |

| Previous ischemic stroke | 60 (13.1) | 22 (15.3) | 23 (9.50) | 15 (13.5) | .324 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 160 (42.1) | 46 (31.9) | 106 (43.4) | 58 (52.3) | .004 |

| Previous neoplasia | 102 (20.4) | 23 (16) | 53 (21.7) | 26 (23.4) | .270 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 123.3 (19.1) | 123 (20.3) | 122 (18.9) | 125 (18.2) | .352 |

| Edema | 70 (14.1) | 11 (7.64) | 31 (12.8) | 28 (25.2) | <.001 |

| ACEI | 116 (23.3) | 37 (25.9) | 58 (23.8) | 21 (18.9) | .416 |

| ARA-II | 74 14.9) | 17 (12) | 37 (15.2) | 20 (18) | .401 |

| ARNI | 208 (41.8) | 70 (49) | 99 (40.6) | 39 (35.1) | .075 |

| Beta-blockers | 416 (83.5) | 124 (86.7) | 202 (82.8) | 90 (81.1) | .441 |

| MRA | 250 (50.2) | 77 (53.8) | 116 (47.5) | 57 (51.4) | .470 |

| Diuretics | 421 (84.5) | 115 (80.4) | 204 (83.6) | 102 (91.9) | .037 |

| Analytical data | |||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.1±1.7 | 13.8±1.58 | 13.4±1.60 | 12.6±1.90 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103/μL | 1.90±1.30 | 1.95±0.98 | 1.95±1.52 | 1.82±1.01 | .635 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.32±0.60 | 1.29±0.59 | 1.32±0.67 | 1.26±0.46 | .704 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min | 52.1±17.5 | 55.6±17.4 | 50.7±17.0 | 50.6±18.5 | .020 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 141±3 | 141±3 | 141±3 | 141±3 | .818 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.5±0.5 | 4.6±0.5 | 4.5±0.6 | 4.4±0.5 | .005 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 144 [71-256] | 122 [65-239] | 147 [73-231] | 150 [77-275] | .742 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 1.568 [900-3.256] | 1.215 [698-2.050] | 1.673 [900-3.276] | 2.226 [1.245-4.290] | <.001 |

| Geriatric syndromes | |||||

| Comorbidity, Charlson index | 3.1±1.9 | 2.80±1.65 | 3.17±2.05 | 3.48±1.84 | .017 |

| Barthel | 92.2±12.5 | 98.0±5.72 | 93.3±10.2 | 82.4±17.3 | <.001 |

| Lawton-Brody, mean | 6±2.1 | 6.72±1.48 | 6.24±1.98 | 4.42±2.16 | <.001 |

| Cognitive status, Pfeiffer test | 1.2±1.7 | 0.74±1.33 | 1.22±1.71 | 1.86±1.97 | <.001 |

| Nutritional risk, MNA-SF | 11.2±1.9 | 11.8±1.68 | 11.2±1.81 | 10.1±2.08 | <.001 |

| Depression, 15-item Yesavage scale | 4.1±3.1 | 2.53±2.01 | 4.11±2.96 | 6.11±3.27 | <.001 |

| Physical function, SPPB | 7±3.2 | 8.50±2.91 | 7.20±3.07 | 4.69±2.72 | <.001 |

| Quality of life, self-reported | 6.8±2 | 7.35±1.90 | 6.77±1.85 | 5.98±2.16 | <.001 |

| Total drugs | 9.60±3.20 | 8.97±2.76 | 9.50±3.12 | 10.8±3.74 | <.001 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARA-II, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors; BMI, body mass index; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

During a median follow-up of 371 [361-387] days, 58 patients (11.6%) died, with noncardiovascular mortality being the leading cause of death (34 patients, 58%). Heart failure was the main cause of cardiovascular mortality (13 patients, 22%). Table 2 shows the association between geriatric syndromes and mortality at 1 year of follow-up. Associations were found between frailty, nutritional risk, comorbidity, and cognitive impairment, and mortality.

Association between geriatric syndromes and mortality at 1 year

| Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity, Charlson index | 1.18 | 1.05-1.33 | .006 |

| Barthel index (< 90) | 0.88 | 0.46-1.66 | .686 |

| Lawton-Brody scale, (< 6) | 1.05 | 0.61- 1.80 | .860 |

| Cognitive status, Pfeiffer (≤ 4) | 2.72 | 1.29-5.73 | .009 |

| Nutritional risk, MNA-SF (≤ 11) | 2.49 | 1.44-4.32 | .001 |

| Frailty, FRAIL* scale | 3.03 | 1.42-6.47 | .004 |

| Fragile, CFS | 2.08 | 1.14-3.81 | .017 |

| Frailty, self-reported; frailty if score ≥ 3 | 1.27 | 1.06-1.51 | .008 |

| Frailty, visual mobility scale; frailty if score ≥ 2 | 2.57 | 1.44-4.58 | <.001 |

| Frailty, SPPB; frailty if score <10 | 1.84 | 0.93-3.65 | .081 |

| Depression, 15-item Yesavage scale | 1.64 | 0.96-2.80 | .071 |

CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

The association between the components of the FRAIL scale and 1-year mortality is shown in .

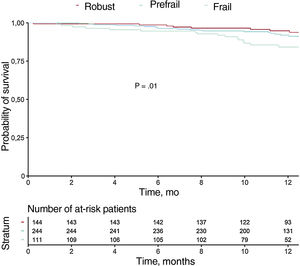

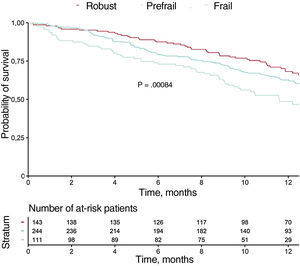

Table 3 shows the variables associated with mortality at 1-year follow-up in the univariate analysis (variables with P <.01 are shown). Figure 1 and figure 2 show the incidences of mortality and mortality or hospital readmission in patients by frailty, respectively. Frail patients had higher mortality during follow-up and a higher rate of the combined endpoint of death or hospital admission. In the multivariate analysis, one of the independent predictors of mortality was frailty identified using the visual mobility scale (hazard ratio [HR],=2.26; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 1.16-4.38; P=.015), whereas the association between frailty using the FRAIL scale and mortality was marginal (HR,=2.35; 95%CI, 0.96-5.71; P=.059) (table 4). After adjustment for confounding variables, the visual mobility scale remained an independent predictor of mortality at 1 year of follow-up (HR,=2.13, 95%CI, 1.08-4.20; P=.02) (table 5).

Variables associated with mortality at 1 year of follow-up

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 0.97 | 0.95-0.99 | .004 |

| Previous neoplasia | 2.12 | 1.22-3.67 | .007 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 1.03 | 1.01-1.05 | .003 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.63 | 0.54-0.73 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.50 | 0.33-0.73 | <.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.46 | 1.16-1.84 | .0001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min | 0.98 | 0.96-0.99 | .004 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | <.001 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 0.89 | 0.82-0.97 | .006 |

| Protein, g/dL | 0.45 | 0.25-0.80 | .006 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 0.37 | 0.18-0.75 | .006 |

| NT-proBNP> 1000 pg/mL | 4.1 | 1.76-9.59 | <.001 |

| TAPSE, mm | 0.88 | 0.82-0.95 | .001 |

| Undilated right ventricle | 0.44 | 0.24-0.79 | .007 |

| Pulmonary systolic pressure, mmHg | 1.03 | 1.01-1.05 | <.001 |

| Furosemide, mg/d | 1.01 | 1.01-1.02 | <.001 |

| Amiodarone | 2.88 | 1.41-5.91 | .004 |

| Flecainide | 14.6 | 1.99-108 | .008 |

| Pfeiffer scale (cognition) ≤ 4 errors | 0.37 | 0.17-0.78 | .006 |

| Malnutrition (MNA-SF ≤ 11) | 2.49 | 1.44-4.32 | .001 |

| Visual mobility scale; frailty if ≥ 2 | 2.57 | 1.44-4.58 | <.001 |

| FRAIL | .010 | ||

| Robust | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Prefrail | 1.75 | 0.85-3.60 | .13 |

| Frail | 3.03 | 1.42-6.47 | .004 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic displacement.

Univariate analysis: variables with P <.01 are shown.

Independent predictors of 1-year mortality for each frailty scale

| HR | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.73 | 0.61-0.87 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.68 | 0.47-0.97 | .032 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.05 | 0.99-1.01 | .194 |

| NT-proBNP> 1000 pg/mL | 2.59 | 1.08-6.20 | .031 |

| Frailty (FRAIL scale) | 2.35 | 0.96 -5.71 | .059 |

| Harrell's C-index=0.7462 | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.74 | 0.61-0.87 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.70 | 0.49-0.98 | .042 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.01 | 0.99-1.01 | .170 |

| NT-proBNP> 1000 pg/mL | 2.57 | 1.07-6.16 | .034 |

| Frailty, visual mobility scale | 2.26 | 1.16-4.38 | .015 |

| Harrell's C-index=0.7481 | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.72 | 0.60-0.86 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.68 | 0.48-0.98 | .037 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.01 | 0.99-1.01 | .134 |

| NT-proBNP> 1000 pg/mL | 2.66 | 1.11-6.37 | .027 |

| Frailty, CFS | 1.48 | 0.78-2.82 | .226 |

| Harrell's C-index=0.7379 | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.71 | 0.59-0.84 | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.70 | 0.48-1.00 | .050 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.01 | 0.99-1.01 | .202 |

| NT-proBNP> 1000 pg/mL | 2.67 | 1.12-6.39 | .026 |

| Frailty, SPPB | 1.46 | 0.67-3.19 | .338 |

| Harrell's C-index=0.7354 | |||

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; HR, hazard ratio; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Independent predictors of 1-year mortality after adjusting for confounders

| HR | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 0.75 | 0.62-0.90 | <.01 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 0.72 | 0.50-1.02 | .06 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .33 |

| NT-proBNP ≥ 1000 pg/mL | 2.41 | 0.97-5.98 | .05 |

| Frailty, visual mobility scale | 2.13 | 1.08-4.20 | .02 |

| LVEF | 1.28 | 0.91-1.80 | .15 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | .22 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min | 0.99 | 0.97-1.02 | .92 |

| ACEI | 1.36 | 0.73-2.55 | .32 |

| ARA-II | 0.47 | 0.15-1.44 | .18 |

| Beta-blockers | 0.90 | 0.41-1.98 | .80 |

| MRA | 1.39 | 0.78-2.47 | .18 |

| Diuretics | 1.50 | 0.44-5.09 | .50 |

| Harrell's C-index=0.7535 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARA-II, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide.

The multivariate analysis with the confounders of the other frailty scales used is shown in .

In total, 164 patients (32.8%) were admitted during follow-up. The variables associated with all-cause admission in the univariate and multivariate analyses are shown in . The variables independently associated with hospitalization were crackles, the daily furosemide dose, and frailty (in this case identified using the Clinical Frailty scale).

DISCUSSIONThe main findings of this study are as follows: a) there was a high prevalence of frailty in the population of ambulatory patients aged at least 75 years with HF followed-up by cardiology specialists in Spain; and b) frailty was independently associated with total mortality and all-cause hospitalization at 1 year of follow-up.

Western societies are currently aging and this trend is expected to continue in the coming years. In these countries, there is an increasing prevalence of geriatric syndromes and, in particular, of frailty and thus their assessment is recommended given their prognostic impact in different clinical situations.8,24,25 Frailty is defined as an aging-associated decrease in physiological reserve, which leads individuals to experience increased vulnerability to stressful situations.8 It is essential that clinicians have available reliable and easy-to-use measures to identify frailty, mainly to plan intervention strategies and adapt care to the characteristics of each patient. Frailty is not easy to assess, because there are 2 different approaches. One approach considers frailty to be a phenotype of poor physical functioning and therefore uses objective physical variables to define it, such as gait speed and grip strength. This approach is represented by use of the Fried19 scale and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).17 The other approach considers frailty to be a multidimensional entity resulting from the accumulation of deficits; under this definition, the most commonly used measures are the Clinical Frailty scale20 and the FRAIL scale.18 The FRAIL scale, due to its simplicity, is easy to use in daily clinical practice.

In Spain, and in the setting of HF, frailty and disability have mainly been studied in patients attended in geriatrics or internal medicine services during hospitalization for acute HF. In the RICA registry,26 Chivite et al. analyzed 2195 patients of at least 75 years of age admitted for acute HF to the internal medicine services of several Spanish hospitals. Most patients (57%) had moderate or severe disability regarding their everyday activities as assessed using the Barthel index, and an association was found between disability and increased all-cause mortality at 1 year of follow-up. Their study did not assess frailty or other geriatric syndromes. Rodríguez-Pascual et al.27 used Fried's definition of frailty to study the prognostic impact of frailty in 497 patients of at least 75 years of age after admission for acute HF and who had been followed up by geriatricians. In total, 57% of the patients were frail and had significantly higher mortality, readmissions, or functional deterioration at 1 year of follow-up. Vidán et al.28 studied 416 patients of at least 70 years of age, who had also been hospitalized for HF and attended in geriatrics, internal medicine, and cardiology services. Using Fried's scale, they identified 76% of the patients as frail (without distinguishing between robust and prefrail patients) and having higher mortality and readmission rates.

On the other hand, very few studies have assessed the prevalence and prognosis of frailty in patients with ambulatory HF. Cacciatore et al.29 studied the association of frailty in 120 ambulatory HF patients (mean age, 74±6.3 years) followed up by the geriatrics department of a hospital. Frailty, as defined by the Frailty Staging System (FSS), was associated with higher mortality at follow-up. In another single-center study, which was conducted in Spain, Lupon et al.30 found higher mortality in patients with geriatric syndromes who had been followed up in an outpatient HF unit. The main limitation of these studies, apart from being single-center studies, is the definition of frailty as a combination of items that are different from each other, sometimes poorly related, and which are closer to the definition of disability than to that of frailty.31

Our study is novel because, unlike previous studies, the FRAGIC registry is the first prospective multicenter study conducted in Spain in which all the patients included were under outpatient follow-up (chronic HF without recent admissions) by cardiology services. This aspect is relevant, given that the assessment of frailty and other geriatric syndromes varies according to the patients’ clinical situation, whether acute or chronic, and that the loss of function on hospital admission is widely documented. Thus, the inclusion of outpatients provides a real-life perspective of the study population, as well as its being the recommended setting for assessing frailty.8 The baseline characteristics of the our study population did not substantially differ from those of previous studies conducted in the setting of geriatrics or internal medicine,26–28 although the percentages of women and patients with HF of nonischemic etiology were lower in our study. Furthermore, in our study, there was lower mortality during follow-up (the main characteristics of the previous studies vs those of our study are shown in ). Consequently, the characteristics and complexity of the elderly patients with HF currently followed up by cardiology services were similar to those of patients followed up by other specialists. This result is in contrast to those of previous studies,32–34 in which associations were found between better prognosis and better baseline characteristics in patients followed up by cardiology services and possibly between better prognosis and the higher prescription of optimal medical treatment or advanced treatments.35 These results suggest the need for further studies in this regard.

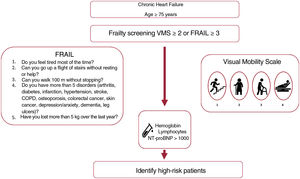

We found an independent association between low hemoglobin levels and higher mortality. This result is in line with those of previous studies, which found associations between greater morbidity and mortality and worse quality of life.36 Previous studies have found that low lymphocyte counts and higher NT-proBNP also identified patients with worse prognosis,6,37–40 although their association with mortality was at the limit of statistical significance when different confounding variables were included in the model (table 5). Frailty, when assessed using the visual mobility scale, was an independent predictor of mortality before and after model adjustment, even though we included many other predictors or confounding factors and despite the sample size. This scale was demonstrated to be a useful and simple measure to identify patients with higher mortality during follow-up. Taken together, hemoglobin, lymphocyte, and NT-proBNP levels, as well as the degree of frailty estimated using the visual mobility scale, can be readily obtained in consulting rooms. These factors can help identify patients with a worse prognosis and who would therefore benefit from a specific approach and close follow-up (figure 3). The relevance of measuring frailty lies in its potential reversibility: it has been shown that frail patients have received clear benefits by their inclusion in multimodal rehabilitation programs.41 Given the observational nature of our study, no specific interventions for frailty were applied despite its identification. It is striking that less than a third of the patients were robust, yet only 1.8% were included in cardiac rehabilitation programs, which highlights current challenges.42-44

Our study has some limitations. This study was an observational study and so we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias. Another possible limitation is that there were slightly fewer women in our study (38%) than in previous studies. However, as mentioned, the mean age of the patients, comorbidities, and baseline characteristics did not differ substantially from those reported by previous studies conducted in other settings.26–28

CONCLUSIONSFrailty is highly prevalent in older patients with ambulatory HF followed up by cardiology services in Spain, and is independently associated with mortality at 1 year of follow-up. Given its potential reversibility, it is vital to identify frailty. Frailty in these patients should be approached and followed up with particular care. New studies are needed on the prevention and treatment of frailty in these patients.

FUNDINGNone declared.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSStudy design: P. Díez-Villanueva, C. Bonanad, F. Formiga, F. J. Martín-Sánchez, M. T. Vidán, A. Ariza, M. Martínez-Sellés. Data collection: C. Jiménez-Méndez, P. Díez-Villanueva, C. Bonanad, C. Ortiz-Cortés, E. Barge-Caballero, J. Goirigolzarri, A. Esteban-Fernández, Á. Pérez-Rivera, M. Cobo, J. López, C. Guerrero, H. García Pardo, C. Robles, D. Iglesias, J. M. García Pinilla, L. López Rodríguez, A. Ariza, M. Martínez-Sellés. Data review and statistical analysis: P. Díez-Villanueva and A. Sanz-García. Manuscript preparation: C. Jiménez-Méndez, P. Díez-Villanueva, C. Bonanad, A. Sanz-García, F. Formiga, F. J. Martín-Sánchez, M. T. Vidán, A. Ariza, M. Martínez-Sellés and F. Alfonso. Review, editing, and approval of the manuscript: all authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

HF is closely associated with aging.

- –

Frailty and other geriatric syndromes are common in elderly patients and this association has been associated with worse prognosis in several cardiovascular diseases.

- –

Frailty is highly prevalent in older patients with ambulatory HF followed up by cardiology services in Spain, and is associated with higher mortality.

- –

Assessment of frailty using scales that are easy to use in routine clinical practice, such as the visual mobility scale, can help identify patients at greater risk of experiencing unwanted events.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2022.04.016