In Spain, the number of female physicians has increased considerably, rising from 35% in 2000 to 51.9% in 2017 (in the United States this figure is 35%; in Italy, 40%; and in the United Kingdom, 46%).1 However, there remain fewer women in positions of responsibility and internal promotion.2–5 The current representation of women in the clinical and academic ranks of Spanish cardiology is unknown. The aims of this study were to analyze: a) the sex distribution in the different subspecialties, and b) the representation of women in cardiology in Spain in all the clinical and academic strata.

We designed a cross-sectional study consisting of a questionnaire sent to heads of department of cardiology from the 98 hospitals across the country, via the Spanish Society of Cardiology and the IESE Business School of Barcelona. The cardiology departments were classified according to the unit type classification used in the SEC-RECALCAR 2016 registry.6

The Spanish Society of Cardiology provided a list of the 98 hospitals. The questionnaire included 26 items related to: a) level of hospital; b) demographic characteristics (sex distribution by age range); c) sex distribution by specialty and subspecialty; d) sex distribution by clinical rank, and e) sex distribution by academic rank.

Subspecialties were assigned according to each cardiologist's primary role. The definitions of fellow and area coordinator were, respectively: a specialist in cardiology undergoing training in a subspecialty, and a cardiologist coordinating a particular health care area, similar to the role of clinical head, but without an official designation. The other positions were as per standard use. Categorical variables are described as No. (%). Differences between percentage rates were analyzed with the chi-square test.

Seventy cardiology departments completed the questionnaire (71% of the hospitals surveyed) (supplementary material). Of all the hospitals that took part, 19.5% were level 1-2; 31.6% were level 3, and 48.9% were level 4. The participation rate was higher in level 3 and 4 hospitals, at 64% in level 1 and level 2, 71% in level 3, and 85.5% in level 4.

In the autonomous communities of Aragón, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León, Extremadura, Murcia, and the Basque Country, 100% of the hospitals surveyed responded, while in the Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, and Valencian Community the participation rate was < 60%. For all 70 hospitals, there were 2353 cardiologists in total, and 40% were women. The women were significantly younger than the men: 67.3% were ≤ 40 years old (P <.001). Women tended to choose less invasive subspecialties (clinical cardiology and imaging) than men (P <.001) (Figure A).

The representation of women by clinical rank is shown in Figure B; the higher up the hierarchy, the lower the representation of women, with women comprising only 19% and 11% of head of section and head of department posts, respectively.

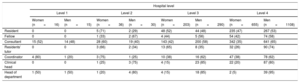

There was higher inclusion of women in lower-category hospitals, and this decreased as the hospital category increased (Table). Specifically, the number of female heads of department was lower in the higher hospital levels, and there were no women in the level 4 hospitals. By autonomous community, we observed that the communities with the highest female representation in cardiology were Aragón (46%), the Basque Country (44%), and Catalonia and Navarra (43%). Last, regarding academic representation, a total of 220 cardiologists reported that they worked as university professors, 66 of whom were women (30%). Among associate professors, 35% were women and only 4 of the tenured professors (7%) were women.

Distribution of Women by Age Range and Hospital Level

| Hospital level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | |||||

| Women (n=16) | Men (n=15) | Women (n=36) | Men (n=30) | Women (n=203) | Men (n=290) | Women (n=655) | Men (n=1108) | |

| Resident | 0 | 0 | 5 (71) | 2 (29) | 48 (52) | 44 (48) | 235 (47) | 267 (53) |

| Fellow | 0 | 0 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 4 (44) | 5 (56) | 54 (42) | 74 (58) |

| Consultant | 15 (52) | 14 (48) | 28 (60) | 19 (40) | 143 (42) | 200 (58) | 342 (35) | 641 (65) |

| Residents’ tutor | 0 | 0 | 3 (66) | 2 (34) | 13 (65) | 8 (35) | 32 (26) | 90 (74) |

| Coordinator | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 10 (38) | 16 (62) | 47 (38) | 78 (62) |

| Clinical head | 0 | 0 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 (15) | 23 (85) | 22 (20) | 87 (80) |

| Head of department | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 4 (15) | 18 (85) | 2 (5) | 39 (95) |

From the results of this study (with a high response rate, making the data robust), we can conclude that: a) overall, including trainees, women comprise almost half of all cardiologists (40% of the total); b) the higher the clinical and academic rank, the lower the female representation: representation is particularly low among heads of department and tenured professors, generating a vertical gap; c) in Spain there is a horizontal gap, as female cardiologists tend to opt for less invasive subspecialties; d) representation of women is lower in higher hospital categories; and e) the distribution of women by autonomous community is homogenous.

Several studies have investigated the possible causes of lower representation of women in senior positions.2–5 Among them is difficulty balancing professional and family life, which, as reported in several national and international surveys, is the main concern for women in medicine.2–5 The responsibility for childcare–falling mainly to women–means that they consider themselves unlikely to be able to compete successfully with other colleagues.4–5 This renunciation could reflect the lower number of women in the cardiological hierarchy, as shown by our data. This lower representation of women in senior posts has also been associated with their lower presence in academic research.4 The likelihood of becoming a tenured professor is significantly lower for women, even when adjusted for factors such as age, productivity, and experience.4

In terms of a potential age bias, although there were more women in the age range 25 to 35 years and there was demographic parity in the age range 35 to 45 years, the differences were more pronounced for the 45 to 55 and 55 to 65 years age ranges. In this last category, one third were women. If we assume that the positions of clinical head require substantial experience and are correlated with age, the 19% and 11% reported in the categories of clinical head and head of department are far below the 30% that would reflect the population distribution.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2018.08.013.