This review article discusses the genetic bases of cardiac arrest with a specific focus on cardiac channelopathies and right ventricular cardiomyopathy. We review the appropriate use of genetic testing in those patients suspected to have inherited cardiac arrhythmias, highlighting the importance of most genotype-phenotype correlations for risk stratification. The article also presents the most recent views on diagnostic criteria and flowcharts for treatment of patients with inherited arrhythmogenic diseases.

Keywords

.

IntroductionIn the past two decades, a growing number of inherited arrhythmogenic diseases have been described, attributing several cases of unexplained arrhythmias in young individuals to distinct heritable conditions. The identification of mutations on the genes responsible for these diseases has facilitated a progressive understanding of their pathophysiology1, 2 and provided the clinician new tools for genetic-based risk stratification and therapy.3 Genetic analysis has become an important tool to identify the molecular substrate in those patients affected or suspected to be affected by an inherited arrhythmogenic disease.

Despite the heterogeneity of substrates and clinical expressivity, genetic testing has a direct impact on clinical practice: it allows the physician to establish/refine diagnosis, including silent carriers, and in selected diseases the identification of a mutation has major impact on risk stratification and treatment of patients.3 The following overview will address the role of genetic testing for each of the most epidemiologically relevant inherited arrhythmogenic diseases: long QT syndrome (LQTS), Brugada syndrome (BrS), short QT syndrome (SQTS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

Long qt syndromeLong QT syndrome is characterized by an excessive prolongation of ventricular repolarization and increased risk of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with a morphologically intact heart.4 The estimated prevalence is between 1:2500 and 1:5000. However, given that up to 2/3 of patients are probably missed and that 10% to 35% have a normal corrected QT (QTc) interval it is likely that the actual prevalence is higher.5, 6 The mean age at onset of symptoms (syncope or sudden death) is 12 years and an earlier onset is usually associated with a more severe outcome.7

Syncope (due to self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia [VT]) and cardiac arrest, often triggered by acute adrenergic activation, are the typical manifestations. When the diagnosis is established, prevention of life-threatening events becomes possible. Antiadrenergic treatment (beta-blockers) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) represent the gist of the LQTS therapy. Appropriate uses of such armamentarium, and in selected cases additional treatments such as gene-specific therapies and left sympathectomy, are often effective in reducing the risk of death. On the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), it is possible to view the QTc interval duration exceeding normal values (ie, QT intervals >440ms in men and >460ms in women).8

Genetic Analysis in Long QT SyndromeIn the majority of cases LQTS is transmitted as an autosomal dominant disease, Romano-Ward syndrome. The autosomal recessive form denominated Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome is characterized by the coexistence of QT prolongation and congenital deafness.

The first three LQTS genes identified by the Keating group were KCNQ1, encoding for the protein that conducts the potassium current IKs; KCNH2, encoding for the channel for the repolarizing potassium current IKr; and SCN5A, encoding for the a-subunit of the sodium channel that conducts the depolarizing sodium current INa.8

In the last 15 years, mutations in other genes encoding for subunits of a variety of ion channels as well as mutations in genes encoding ion channels’ regulatory proteins were discovered in LQTS patients. At present, 13 different variants of LQTS have been published (Table 1).

Table 1. Genes Associated With Long QT Syndrome.

| Phenotype | Variant | Gene | Protein | Functional defect |

| Long QT syndrome | LQT1 | KCNQ1 | KvLQT1 (potassium channel α subunit) | Loss of function |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 | HERG (potassium channel α subunit) | Loss of function | |

| LQT3 | SCN5A | Nav1.5 (sodium channel α subunit) | Gain of function | |

| LQT4 | ANK2 | Ankyrin B, anchoring protein | Loss of function | |

| LQT5 | KCNE1 | MinK (potassium channel β subunit) | Loss of function | |

| LQT6 | KCNE2 | MiRP (potassium channel β subunit) | Loss of function | |

| LQT7, Andersen syndrome | KCNJ2 | Kir2.1 (potassium channel α subunit) | Loss of function | |

| LQT8, Timothy syndrome | CACNA1c | Cav1.2 (L-type calcium channel α subunit) | Gain of function | |

| LQT9 | CAV3 | Cardiac caveolin gene | Gain of function | |

| LQT10 | SCN4B | Sodium channel β4 subunit | Gain of function | |

| LQT11 | AKAP9 | A-kinase-anchoring protein | Reduced IKs current | |

| LQT12 | SNTA1 | Syntrophin | Increased sodium current | |

| LQT13 | KCNJ5 | Kir 3.4 subunit of IKAch channel | Loss of function |

LQTS genes affect ionic currents, either directly (ion channel mutations) or indirectly (chaperones and/or other modulators).9 Two variants, LQT7 and LQT8, are characterized by the presence of an extracardiac phenotype resulting in 2 distinct syndromes. LQT7 (Andersen syndrome), caused by mutations on KCNJ2 gene, is a rare variant (<1%): it includes periodic paralysis and dysmorphic features. The ECG is characterized by the presence of marked U waves and ventricular arrhythmias including bidirectional VT10. LQT8 (Timothy syndrome)11 is caused by gain-of-function mutations on CACNA1c gene encoding for the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel. Interestingly, more than 90% of the patients affected by LQT8 carry the same G406R mutations: this differs from the other genetic variant of LQTS that is characterized by extreme heterogeneity of different mutations. Timothy syndrome patients show a marked prolongation of QT interval associated with a complex phenotype that includes syndactyly, atrioventricular block, congenital heart defects, autism, developmental disorders, and reduced immune response.

A genetic defect is identified in 60% to 72% of LQTS patients12 and >90% of the genotyped patients belong to the first three variants (LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3). Thus, comprehensive screening is not currently indicated. The analysis of ECG findings along with personal and family history may help in directing the approach to the test.13 Of note, the probability of positive genotyping is highest (up to 72%) when performed in those with the highest phenotypic probability of having the syndrome,14 reinforcing the role of phenotype correlation in guiding rational genotyping decisions.

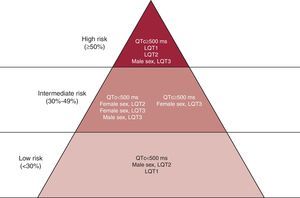

The screening on ANK2, KCNJ2, and CACNA1C is indicated only in the presence of specific phenotypes suggesting the involvement of these genes. The genotype has a direct clinical impact in LQTS: gene-specific differences have been described in terms of morphology of the ST–T wave complex, triggers for cardiac events,15 and risk of cardiac events.7, 16, 17 Genotype-phenotype studies have provided important information regarding the effect of location, coding type, and biophysical function of the channel mutations on the phenotypic manifestations and clinical course of LQTS patients.18 Based on these findings, there is consensus that LQT2 and LQT3 genotypes show a worse prognosis and relatively poor response to beta-blocker therapy. With regard to treatment in genotyped patients, beta-blocker therapy has been associated with a significant reduction in the rate of cardiac events in patients with LQT1 and LQT2 mutations, but no evident reduction in those with LQT3 mutations.19 An ICD implant for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac arrest may be considered in these LQTS variants when associated with QTc >500ms and an early onset of cardiac events (<7 years of age). We can conclude that the locus of the causative mutation affects the clinical course in LQTS and, along with sex, modulates the effects of the QTc on clinical manifestations. From these data our group proposed an approach to risk stratification based on these variables (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Risk stratification in Long QT Syndrome, according to the QTc interval duration, genotype, and gender. QTc, corrected QT. Reproduced with permission from Priori et al. 7

From this brief overview, it is easy to see how genotyping can have significant clinical impact in the care plan for LQTS patients and is indeed ready for prime time.

Influence of Genotype on the Clinical Management of Long QT SyndromeAlthough genetic heterogeneity in LQTS is remarkable, 3 genes are mainly involved and explain >90% of LQTS cases: KCNQ1 (LQT1), KCNH2 (LQT2), and SCN5A (LQT3). These 3 most prevalent genetic variants of LQTS have different features, risk indicators, and response to therapy. Thanks to these discoveries, genotype has become part of the risk stratification scheme for LQTS patients.

The earliest genotype-phenotype correlations in LQTS pointed out that LQT1 patients experience most of their symptoms during sport activities, especially swimming, whereas LQT3 individuals are at a higher risk of arrhythmias during sleep or at rest and LQT2 patients experience events in association with loud noise.15 It became evident that, together with sex and QT interval duration, genotype is a determinant of the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) and of response to therapy.7, 16 As demonstrated in Figure 1, LQT2 females and LQT3 men with QT interval >500ms fall into the higher risk category independent of other factors.7 Similarly, although LQT1 patients tend to have an optimal response to beta-blockers, LQT2 and LQT3 patients experience recurrences despite full-dose beta-blockers.16 On the basis of these data and on the opinion of experts, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology 2006 Guidelines for the prevention of SCD20 state that the presence of a QTc interval >500ms in LQT2 and LQT3 opens the possibility of implanting a prophylactic ICD (Figure 1). Interestingly, based on the evidence that LQT3 is caused by an excess of inward sodium current, it was suggested that mexiletine may exert an antiarrhythmic effect in LQT3 patients by reducing the QTc interval duration through its sodium channel blocking effect.21

Recently, clinical evidence showed that the clinical response to mexiletine is influenced by the type of mutation, and often mexiletine could be ineffective22 or even harmful.23

Brugada syndromeBrS is an inherited arrhythmogenic disease characterized by a unique electrocardiographic pattern of ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3 and incomplete or complete right bundle branch block in the absence of structural heart disease.24

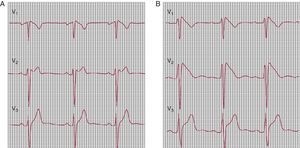

Only one ST-segment pattern is considered diagnostic: elevation in V1, V2, and V3 with coved morphology of at least 2mm, the so-called type I ECG (Figure 2B). This diagnostic pattern may be intermittent. Quite often the presenting ECG suggests a possible BrS (saddle-back type ST-segment elevation) (Figure 2A). Intravenous administration of a single bolus of sodium channel blockers (procainamide, flecainide, or ajmaline) may convert a concealed or nondiagnostic pattern into a coved type 1 diagnostic pattern25, 26 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flecainide test in a patient with suspected Brugada syndrome. A, baseline electrocardiogram (type 2). B, Flecainide 2mg/Kg; diagnostic pattern (type 1).

The estimated worldwide prevalence is 0.10%27 and may be greater in endemic areas of Southeast-Asia.28 The majority of patients with clinical diagnosis are men: it is still unknown how sex modulates the manifestation of the disease.24, 25, 29

The most common clinical manifestations of BrS are syncope or SCD caused by ventricular tachyarrhythmias mostly occurring during sleep or at rest; other arrhythmic triggers could be fever or large meals. Supraventricular arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation are also present in 15% to 20% of the patients with a BrS diagnosis.30 Atrioventricular block and intraventricular conduction delays are part of the phenotype of BrS.31 By extension, the presence of late potentials should be regarded as a clinical marker of the disease as they occur in some 50% of clinically affected patients.

So far, no medical therapy resulted effective in preventing arrhythmias and sudden death in BrS and ICD implantation is the only available treatment.32 Isoproterenol infusion is useful in acutely controlling arrhythmic storms. The only drug so far used with some success is quinidine33; it may be considered as an adjunctive therapy in cases of recurrent arrhythmias and frequent ICD discharges. Unfortunately, long-term quinidine treatment is affected by a relevant drop-off rate due to gastrointestinal side effects.

Risk stratification to select high-risk patients who are likely to benefit from an ICD is therefore crucial. General agreement exists that a history of syncope in the presence of a spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern identifies subjects at a higher risk of SCD.32 When type 1 ECG is elicited through pharmacological challenge but is never spontaneously present, the arrhythmic risk is lower.32

Unfortunately, a high percentage of the patients with a BrS diagnosis fall into the intermediate risk category, because they are asymptomatic and may present a type 1 spontaneous pattern. Therefore, clinicians and scientists face the challenge of identifying new markers to further stratify the arrhythmic risk in this group, thus selecting who should receive an ICD. Although programmed electrical stimulation was proposed as a risk stratification metric, evidences are accumulating that dismiss its clinical usefulness32, 34, 35, 36; a family history for sudden death and/or the presence of a genetic mutation does not influence the arrhythmic risk. Recent data are suggesting that the presence of QRS fragmentation may correlate with worse prognosis.36, 37

Genetic Analysis in Brugada SyndromeThe disease is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. The genetic component of the syndrome is attributed to mutations on 10 different genes (Table 2). The first gene linked to BrS was discovered in 1998 as the SCN5A gene encoding for the cardiac sodium channel; this is the same gene linked to LQT3. As of today, most genotyped patients carry a mutation on this gene.38

Table 2. Genes Associated With Inherited Arrhythmogenic Diseases.

| Phenotype | Variant | Gene | Protein | Functional defect |

| Brugada syndrome | BrS1 | SCN5A | Cardiac sodium channel alpha sub-unit (Nav1.5) | Loss of function |

| BrS2 | GPD1-L | Glycerol-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase | Loss of function | |

| BrS3 | CACNA1c | L-type calcium channel alpha subunit (Cav1.2) | Loss of function | |

| BrS4 | CACNB2 | L-type calcium channel beta-2 subunit | Loss of function | |

| BrS5 | SCN1B | Cardiac sodium channel beta1 subunit | Loss of function | |

| BrS6 | KCNE3 | Transient outward current beta subunit | Gain of function | |

| BrS7 | SCN3B | Cardiac sodium channel beta-3 subunit | Loss of function | |

| BrS8 | MOG1 | Nucleocytoplasmic and microtubule transport | Loss of function | |

| BrS9 | KCNE5 | Transient outward current beta subunit | Gain of function | |

| BrS10 | KCND3 | ITo potassium channel (Kv4.3) | Gain of function | |

| Short QT syndrome | SQTS1 | KCNH2 | IKr potassium channel alpha subunit (HERG) | Gain of function |

| SQTS2 | KCNQ1 | IKs potassium channel α subunit (KvLQT1) | Gain of function | |

| SQTS3 | KCNJ2 | IK1 potassium channel (Kir2.1) | Gain of function | |

| SQTS4 | CACNA1c | L-type calcium channel alpha subunit (Cav1.2) | Loss of function | |

| SQTS5 | CACNB2 | L-type calcium channel beta-2 subunit | Loss of function | |

| SQTS6 | CACNA2D1 | L-type calcium channel delta-1 subunit | Loss of function | |

| Catecholaminergic VT | CPVT1 | RyR2 | Cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) | Diastolic calcium release |

| CPVT2 | CASQ2 | Cardiac calsequestrin (CASQ2) | Diastolic calcium release |

VT, ventricular tachycardia.

The sodium current is definitely an important player in the pathogenesis of BrS as demonstrated by the fact that 3 additional genes implicated in the disease (GPD1-L, SCN1B, and SCN3B) influence INa.39, 40, 41

Recently, CACNA1c and CACNB2 genes, encoding for the a-and b-subunits of the cardiac calcium channel, were associated with the BrS phenotype. Loss-of-function mutations in these genes have been related to the disease.42 The first BrS patients described in the literature as carriers of mutations in the CACNA1c and CACNB2 genes presented with a distinctive phenotype combining short QT interval and type I BrS ECG pattern. Thus, it's important to evaluate accurately the presence of short QT interval and/or BrS ECG pattern as part of a single phenotype, to better address genetic screening in these patients.

Since the relative prevalence of mutations on the other genes related to BrS is unknown (and likely very low), the routine screening of these genes, with the exception of SCN5A, has an uncertain diagnostic value. Furthermore, genetic heterogeneity of BrS is likely to be even greater as mutation screening on the known genes allows identifying a mutation in 25% to 30% of clinically affected patients. As a consequence, genetic screening helps confirming the clinical diagnosis and allows identifying silent gene carriers but, at variance with what happens in LQTS, so far there is no evidence that results of genetic testing influence clinical management or risk stratification in BrS.32

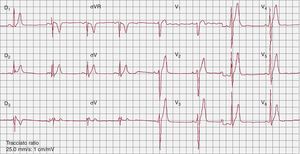

The short qt syndromeIn 2000, Gussak et al.43 identified a new arrhythmogenic disease characterized by a shorter than normal QT interval (<350ms) (Figure 3), ventricular and atrial arrhythmias, and SCD. Recognizing that only a limited number of SQTS patients have been reported, it seems that the occurrence of SCD as first manifestation is not infrequent. Preliminary attempts at risk stratification have been unsuccessful44 due to the low number of patients, and ICD implantation is the primary therapy. By prolonging the QT interval, hydroquinidine seems to be effective in preventing ventricular tachyarrhythmia induction and arrhythmic events during long-term follw-up.45

Figure 3. Baseline electrocardiogram in a patient with Short QT Syndrome (QT/QTc, 300/300ms).

Mutations in the KCNH2, KCNQ1, KCNJ2, CACNA1c and CACNB2 genes were found in individuals diagnosed with SQTS.42, 46, 47, 48 At present, however, only a minority of patients received a genetic characterization.

According to recent data49 approximately 20% of patients with short QT are successfully genotyped; therefore the value of genetic testing in the syndrome is limited and does not bear prognostic implications. Data on a limited cohort of patients suggest that carriers of KCNH2 mutations may present with shorter QT interval.49 Risk stratification and management of SQTS is still ill-defined.

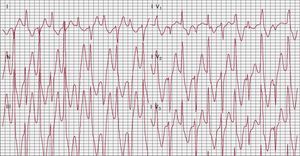

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardiaCatecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a disorder of intracellular calcium handling.50 The estimated prevalence is 1:7000-1:10 000. It is one of the most lethal inherited arrhythmogenic diseases, with a natural history showing up to 30% SCD before age 40 in the absence of antiadrenergic therapy.51, 52 The disease manifests with adrenergically mediated life-threatening arrhythmias that cause syncope and/or cardiac arrest with onset during the pediatric age. The surface ECG is unremarkable; therefore, the diagnosis is mostly based on symptoms and on the detection of stress-induced arrhythmias during exercise stress test or Holter recording. Patients also present supraventricular arrhythmias, mainly bursts of supraventricular tachycardia or of atrial fibrillation that overlap with ventricular extrasystoles and VT. During exercise stress testing, very often patients experience progressive increase in the complexity of the arrhythmia until VT develops. Bidirectional VT is almost diagnostic for the disease: it is characterized by beat-to-beat 180° rotation of the QRS complexes (Figure 4). Some patients do not present bidirectional VT and during exercise develop polymorphic VT.51, 52

Figure 4. Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia during exercise stress test in a patient affected by catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Whenever CPVT diagnosis is established, beta-blockers should be administered.20 Although this approach affords protection in the majority of patients, approximately 30% of patients experience at least one arrhythmic event while on therapy.51, 53, 54 More recently, Watanabe et al.55 reported suppression of arrhythmias in 2 CPVT patients when treated with oral flecainide. Even if data on larger series are needed before proposing the use of flecainide as medical treatment in CPVT, these results are encouraging and worth further exploration.

Genetic Analysis in Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular TachycardiaInvestigations to disclose the molecular basis of CPVT led to the identification in affected individuals of mutations on 2 genes encoding for proteins of the sarcoplasmic reticulum: the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and cardiac calsequestrin (CASQ2), associated with the autosomal dominant and recessive forms of CPVT, respectively.56, 57

It has been demonstrated that mutations on RyR2 and CASQ2 genes result in an increased calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and promote the onset of triggered arrhythmias.

Some 70% of genotyped patients carry a mutation on the RyR2 gene,51 while the prevalence of CASQ2 mutations is low (∼7% in our cohort).58 Genetic analysis is logistically complicated by the fact that RyR2 is one of the largest genes in the human genome, and genotyping turnaround time is long.

A coherent RyR2/CASQ2 screening approach must include two additional important observations: first, 20% of mutation carriers have no phenotype (incomplete penetrance) and second, sudden cardiac arrest can be the first clinical presentation of the disease in up to 62% of cases.58 Therefore, CPVT may be regarded as a cause of adrenergically mediated idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, justifying genetic testing in such instances.

Anecdotal reports show that KCNJ2 (LQT7) mutations may cause a CPVT phenotype.59 This point is particularly important to consider for RyR2 and CASQ2-negative patients, since KCNJ2 mutations are usually associated with a more benign prognosis and sudden death is considered an exceptional event in these cases.10 Thus, molecular diagnosis may provide important prognostic insight in these cases.

Early CPVT genetic evaluation is very important for all family members of CPVT probands, for presymptomatic diagnosis and appropriate reproductive counseling. Furthermore, as beta-blockers are often an effective treatment, genetic diagnosis of CPVT is relevant in the prevention of life-threatening events – improving prognosis substantially,51 and worthy of prime time status.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathyArrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is a disorder of the cardiac desmosome, a protein responsible for supporting structural stability through cell–cell adhesion, regulating transcription of genes involved in adipogenesis and apoptosis, and maintaining proper electrical conductivity through regulation of gap junctions and calcium homeostasis.60 The estimated prevalence of the disease is 1:5000 and it is thought to be a major contributor to SCD in young people and athletes worldwide, with an annual mortality rate of 2% to 4%.61

A predominantly autosomal dominant disease, ARVC is characterized by myocardial degeneration and fibrofatty infiltration of the right ventricular free wall, the subtricuspid region, and the outflow tract. A rare autosomal recessive variant (Naxos disease) characterized by typical myocardial involvement, palmar keratosis, and woolly hair has also been described.62 The histopathophysiology of ARVC involves the progressive replacement of myocardial tissue with fibro-fatty tissue, predominantly in the right ventricle, but often also involving the left (in up to 25% of cases), resulting in malignant arrhythmia of ventricular origin.63

Genetic Analysis in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular CardiomyopathyMutation in genes encoding any of the 5 major components of the desmosome can result in ARVC, but PKP2 (encoding plakophilin-2), DSG2 (encoding desmoglein-2), and DSP (encoding desmoplakin) harbor the majority of identified mutations: 27%, 26%, and 11%, respectively.64 In pooled analysis, a single, heterozygous mutation is identified in 39.2% of individuals with ARVC who have undergone full sequence analysis of all the desmosome genes.65

According to the revised ARVC Task Force criteria,66 the identification of pathogenic mutation is a major criterion for diagnosis, underlying the potential utility of clinical genetic testing in the diagnosis of ARVC.

Enabling cascade screening in relatives becomes the principal issue, as a positive diagnosis in a family member changes the probability of disease in an individual suspected of the disease to 1:2 from 1:1000 to 1:500067; therefore, genotyping in ARVC may be recommended for confirmation of select index cases. First-degree relatives should be screened clinically with 12-lead ECG, echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; genotyping is not yet ready for a first-line, prime-time slot.

Currently, there is no clear risk stratification that may be gleaned from genotyping ARVC; recent literature has shown that PKP2-positive patients have symptom and arrhythmia onset at an earlier age, but prospective defibrillator events were not significantly different from the PKP2-negative cohort.68

Current limitation and role of genetic testingWith the increased use of genetic testing, genetic counseling has become a fundamental part of the process. In some cases the benefits gained from identifying a pathogenic mutation can be substantial; in others the same discovery could have important drawbacks.69 Diagnosis, prevention, risk of events, and response to therapy are all influenced by the genotype, although its clinical role is essentially disease-specific.

Genotyping may not be appropriate for every case of inherited arrhythmogenic disease, and a decision whether to offer analysis should be made within the context of and with the cooperation of each family. Furthermore the identification of a remarkable number of minor genes accounting for few cases increases the uncertainty of interpretation. The recent consensus document jointly published by Heart Rhythm Society and European Heart Rhythm Association has clearly outlined pro and cons of genetic testing for each inherited disorder.70, 71 The document also outlines the interesting concept of “key genes”, meaning the genes that, for each condition, should be included in an “ideal” screening in order to maximize the possibility of achieving clinically useful results and to minimize the risk of identifying variants of unknown significance, which may imply major problems in interpreting the results of genetic testing. The indications of genetic testing for the inherited arrhythmogenic disorders described in this article and outlined in the consensus document are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Indications for Genetic Testing.

| Disease | Confirmed diagnosis/symptomatic | Asymptomatic | Family members |

| LQTS | Recommended: KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A | Recommended QT>500 (480 Ped); otherwise may be indicated | Recommended |

| CPVT | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| BrS | Can be useful | Not indicated if type 2 or 3 | Recommended |

| SQTS | May be considered | − | Recommended |

| ARVC | Can be useful | May be considered (1 major or 2 minor criteria) | Recommended |

ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; BrS, Brugada syndrome; CPVT, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; LQTS, long QT syndrome; SQTS, short QT syndrome.

The past 20 years have witnessed an incredible advancement in the appreciation of the role exerted by genetics in cardiac arrhythmias. The growing body of information now available opens new challenges, calling for an increasing interaction between the cardiologist and basic scientists. Once a genetic mutation is discovered, it becomes important to integrate bench and clinical studies to assess its potential deleterious effect and define the best management strategy for mutation carriers.

The ability of the care team involved to determine pretest probability of disease drives the appropriate usage of the technology. Overall, these observations highlight the concept that future research aimed at using genetic information for clinical and therapeutic management of patients with inherited arrhythmogenic disease might include the need for functional characterization, in order to be able to provide tailored patient-specific healthcare. We support the view that the practical value of genetic analysis is different in the various inherited arrhythmogenic conditions; it is directly connected to the multidisciplinary approach where the cardiologist, the clinical geneticist, and the molecular biologist are coprotagonists of a medical action aimed to achieve the best use of the genetic information. Genetic testing for inherited cardiac arrhythmias should not be the first test performed, but clearly has a prime place in current practice.

Altogether, the newly developed field of cardiovascular genetics is facing future challenges to fill the existing gaps separating current practice from individualized patient management.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Corresponding author: Medicina Molecolare, IRCCS Fondazione Salvatore Maugeri, Via Maugeri 10/10A, 27100 Pavia, Italy. silvia.priori@fsm.it