The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) increases with age and peaks at the age of ≥80 years (17.7%).1 Decisions on oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy are challenging in patients of this age due to a higher stroke and bleeding risk. Although direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been shown to be an attractive option for elderly patients—they are at least as effective as vitamin K antagonists and substantially reduce intracranial hemorrhage—they are clearly underused.2

The aim of this study was to assess the use of DOACs in a contemporary clinical series of patients aged ≥80 years and to analyze predictors of DOAC use and the influence of age on choice of doses.

The REFLEJA AF study is a prospective registry of 1039 consecutive outpatients with nonvalvular AF (NVAF) evaluated between October 2017 and June 2018 at a single hospital in Jaen, Spain. The registry includes all patients aged ≥18 years with NVAF evaluated by the cardiology unit. We compared the baseline characteristics of patients aged <80 years and ≥80 years by bivariate analysis, using the chi-square test for qualitative variables and the t test for quantitative variables. We then performed binary logistic regression to identify independent predictors of DOAC use in these populations and calculated their respective odds ratios (ORs).

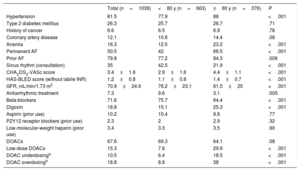

The characteristics of the population are summarized in table 1. Compared with younger patients, the group of patients aged ≥80 years (n=376) comprised significantly more women (57.7% vs 41.5%, P<.001) and patients with heart failure (29.8% vs 20.2%, P<.001) or vascular disease (19.7 vs 12.8%, P=.003). Although the differences were not significant, older patients were also more likely to have a history of bleeding (5.9% vs 3.8%, P=.12) or stroke (9.3% vs 7.1%, P=.20).

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the study population by age

| Total (n=1039) | <80 y (n=663) | ≥80 y (n=376) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 81.5 | 77.9 | 88 | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 26.3 | 25.7 | 26.7 | .71 |

| History of cancer | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | .78 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12.1 | 10.8 | 14.4 | .08 |

| Anemia | 16.3 | 12.5 | 23.2 | <.001 |

| Permanent AF | 50.5 | 42 | 66.5 | <.001 |

| Prior AF | 79.8 | 77.2 | 84.3 | .006 |

| Sinus rhythm (consultation) | 35 | 42.5 | 21.9 | <.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.4±1.6 | 2.9±1.6 | 4.4±1.1 | <.001 |

| HAS-BLED score (without labile INR) | 1.2±0.8 | 1.1±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | <.001 |

| GFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 70.9±24.9 | 76.2±23.1 | 61.5±25 | <.001 |

| Antiarrhythmic treatment | 7.3 | 9.6 | 3.1 | .005 |

| Beta-blockers | 71.6 | 75.7 | 64.4 | <.001 |

| Digoxin | 18.8 | 15.1 | 25.3 | <.001 |

| Aspirin (prior use) | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.8 | .77 |

| P2Y12 receptor blockers (prior use) | 2.3 | 2 | 2.9 | .32 |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin (prior use) | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.5 | .90 |

| DOACs | 67.6 | 69.3 | 64.1 | .08 |

| Low-dose DOACs | 15.3 | 7.6 | 29.9 | <.001 |

| DOAC underdosinga | 10.5 | 6.4 | 18.5 | <.001 |

| DOAC overdosingb | 18.8 | 8.8 | 38 | <.001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; INR, international normalized ratio.

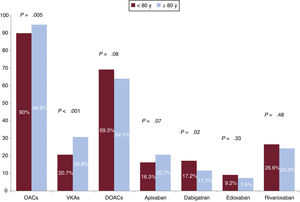

Despite their less favorable profile, patients aged ≥80 years were more likely to be on AOCs (94.9% vs. 90% for those aged <80 years, P=.005). The difference for the prescription of DOACs, however, was not significant (64.1% v. 69.3%; P=.08), although a higher proportion of older patients were on low doses (29.9% vs 7.6%, P<.001). The only significant difference observed in terms of the use of specific DOACs was for dabigatran, which was prescribed less often to patients aged ≥80 years (figure 1).

On multivariate analysis, an age ≥80 years was not associated with a lower use of DOACs (OR=1.16; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.58-2.31; P<0.67). By contrast, both heart failure (OR=0.60; 95%CI, 0.40-0.90; P=.013) and chronic kidney failure (CKF) (OR=0.55; 95%CI, 0.41-0.76; P<.001) were independent predictors of lower DOAC use.

Generally speaking, there is sufficient evidence to recommend AOC therapy to elderly patients as it produces a net benefit in terms of a reduced risk of death, ischemic stroke, and intracranial hemorrhage (in this last case even in patients with a HAS-BLED score ≥3).3 There is also evidence that AOCs result in an absolute reduction of stroke risk in elderly patients and that the reduction in this population is even higher than in younger patients.4

One notable finding of our study was that over 90% of patients with NVAF were on AOC therapy, and there were no differences between patients aged <80 years and ≥80 years. This rate is even higher than that reported in a quality US clinical practice registry, where less than 80% of patients with NFAF were on AOCs and use was higher in younger patients.5

Appropriate choice of anticoagulant dose is necessary to ensure effective protection against stroke and to prevent an increased risk of bleeding. Subjective judgements based on age could erroneously lead to the prescription of low DOAC doses in elderly patients if other factors such as low body weight (<60kg) or CKF are not taken into account. It is noteworthy that underdosing (18.5%) and overdosing (38%) were common in our series, even though almost 35% of patients had a glomerular filtration rate <50mL/min, which is a criterion for using lower doses for certain DOACs. After adjusting for sex, bleeding risk, CKF, and prior bleeding, an age of ≥80 years was independently associated with a 3-fold increased odds of underdosing (OR=3.01; 95%CI, 1.83-4.92; P<.001). It was also associated with an increased odds of overdosing (OR=3.11, 95%CI, 1.66-5.84, P<.001), although the strongest independent predictor of overdosing, irrespective of age, was CKF, as 99% of these patients had a glomerular filtration rate <60mL/min.

In conclusion, our findings from a clinical AF registry indicate that DOAC use among elderly patients may be common, although the prognostic benefits of this treatment might be lower than expected, as we found that age ≥80 years was associated with both an inappropriate use of low doses and an excessive use of higher-than-indicated doses (primarily in patients with CKF).

FundingThis study was partially funded by an unconditional grant from Daiichi-Sankyo and Bayer.

We would like to thank Dr Ruiz Ortiz for revising this manuscript and providing helpful comments.