On 14 March 2020, a state of alarm was declared in Spain because of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, and home confinement was made mandatory to control the high number of cases of this infection. In the health sector, all nonpriority medical activity was limited, but urgent activity was maintained. Nonetheless, during the first weeks of confinement, a decrease of up to 40% was observed across the country in the number of alerts for ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction.1 According to reports from other countries, there may have been a similar reduction in the treatment of bradyarrhythmia.2,3 The present study analyzes the impact of the first COVID-19 wave on the treatment of severe bradyarrhythmia in Spain.

Through the Cardiac Pacing Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, centers with activity in this field were requested to collaborate in the study. An online database was provided to record the number and characteristics of pacemaker implantation procedures with a preferential/urgent indication carried out between 15 March and 15 May, 2019, and the same dates in 2020, in order to perform a comparison. Scheduled elective procedures, battery replacements, lead repositioning, and pacing system extensions were not included. The deadline for submitting the data was 15 June, 2020.

Data were sent by 31 centers in 13 autonomous communities of Spain. The general characteristics are shown in table 1. Although the populations were similar during the 2 periods, there was a significant reduction in the number of procedures performed in asymptomatic patients (10% vs 6.3%; P=.014) and those with presyncope (21.9% vs 15.8%; P=.005) relative to the 2019 activity. Complete atrioventricular block (cAVB) was the most common cause in the 2 periods, but it was significantly more frequent in 2020 (41.6% vs 47.7%; P=.023).

Characteristics of the total population, 2019 and 2020

| Total | 2019 | 2020 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of the population | ||||

| Age, years | 80±12.4 | 81±11.8 | 80±13 | .700 |

| Women | 611 (42.3) | 376 (42.9) | 235 (41.4) | .610 |

| HT | 1068 (73.9) | 640 (73) | 428 (75.4) | .403 |

| DM | 485 (33.6) | 277 (31.6) | 208 (36.6) | .087 |

| Heart disease | 762 (52.7) | 468 (53.4) | 294 (51.8) | .551 |

| Dilated | 31 (2.1) | 17 (1.9) | 14 (2.5) | .500 |

| Hypertensive | 200 (13.8) | 129 (14.7) | 71 (12.5) | .235 |

| Hypertrophic | 18 (1.2) | 14 (1.6) | 4 (0.7) | .135 |

| Ischemic | 211 (14.6) | 121 (13.8) | 90 (15.8) | .282 |

| Valve disease | 249 (17.2) | 159 (18.1) | 90 (15.8) | .261 |

| Others | 53 (3.7) | 28 (3.2) | 25 (4.4) | .233 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 124 (8.6) | 88 (10) | 36 (6.3) | .014 |

| Asthenia | 171 (11.8) | 99 (11.3) | 72 (12.7) | .425 |

| Dyspnea | 276 (19.1) | 154 (17.6) | 122 (21.5) | .064 |

| Presyncope | 282 (19.5) | 192 (21.9) | 90 (15.8) | .005 |

| Syncope | 547 (37.9) | 316 (36) | 231 (40.7) | .076 |

| Cardiorespiratory arrest | 22 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 9 (1.6) | .877 |

| ECG abnormality justifying the device | ||||

| Sinus dysfunction | 183 (12.7) | 118 (13.5) | 65 (11.4) | .261 |

| 1st degree block, | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | .832 |

| Type 1 2nd degree block, | 17 (1.2) | 9 (1) | 8 (1.4) | .510 |

| 2:1 block | 132 (9.1) | 83 (9.5) | 49 (8.6) | .589 |

| Type 2 2nd degree block | 69 (4.8) | 46 (5.2) | 23 (4) | .298 |

| Complete block | 636 (44) | 365 (41.6) | 271 (47.7) | .023 |

| Slow AF | 124 (8.6) | 78 (8.9) | 46 (8.1) | .598 |

| Blocked AF | 159 (11) | 93 (10.6) | 66 (11.6) | .547 |

| Bifascicular block | 37 (2.6) | 28 (3.2) | 9 (1.6) | .059 |

| Trifascicular block | 34 (2.4) | 21 (2.4) | 13 (2.3) | .897 |

| Alternating block | 11 (0.8) | 6 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | .675 |

| Bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome | 23 (1.6) | 17 (1.9) | 6 (1.1) | .191 |

| AVN ablation | 8 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 2 (0.1) | .406 |

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | .832 |

| Clinical situation/severity | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 40±21 | 41±24 | 40±20 | .023 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 63.3±36.7 | 65.2±37.1 | 61.1±37.3 | .050 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 1.230±3.330 | 1.012±2.885 | 1.429±4.846 | .010 |

| LVEF, % | 60±5 | 60±6.5 | 60±5 | .039 |

| ICU requirement | 445 (32.4) | 276 (33.2) | 169 (31.3) | .468 |

| Age in ICU, y | 79.2±12.6 | 79.7±13.6 | 79±12 | .900 |

| Vasoactive drug requirement | 383 (26.5) | 200 (22.8) | 183 (32.2) | .001 |

| Temporary PM requirement | 228 (15.8) | 137 (15.6) | 91 (16) | .734 |

| Implantation and hospital stay | ||||

| Total days of hospitalization | 4±6 | 4±6 | 3±5 | < .001 |

| Days to implantation | 2±3 | 2±4 | 1±3 | < .001 |

| Days hospitalized following implantation | 1±2 | 1±2 | 1±2 | < .001 |

| Pacing mode | .524 | |||

| AAI | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | .284 |

| VVI | 532 (36.8) | 321 (36.6) | 211 (37.1) | .834 |

| VDD | 53 (3.7) | 35 (4) | 18 (3.2) | .417 |

| DDD | 827 (57.2) | 504 (57.5) | 323 (56.9) | .821 |

| CRT | 26 (1.8) | 13 (1.5) | 13 (2.3) | .226 |

| Complications | 64 (4.4) | 43 (4.9) | 21 (3.7) | .276 |

| Pericardial effusion | 4 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | .487 |

| Perforation | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | .607 |

| Displacement | 24 (1.7) | 17 (1.9) | 7 (1.2) | .305 |

| Hematoma | 18 (1.2) | 11 (1.3) | 7 (1.2) | .971 |

| Pneumothorax | 11 (0.8) | 7 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | .552 |

| Death | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | .559 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AVN, atrioventricular node; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; HT, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, amino-terminal fraction of brain pro-natriuretic peptide; PM, pacemaker.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Patients in the 2020 period had slightly worse creatinine clearance values (median, 65.2 vs 61.1mL/min; P=.019) and higher levels of the amino-terminal fraction of brain pro-natriuretic peptide (median, 1012 vs 1429; P=.010). Although these factors could indicate greater severity, there were no differences in the percentage of patients treated in intensive care units (ICUs) or in transvenous pacemaker use. The only difference found was more frequent vasoactive drug prescription in 2020 (22.8% vs 32.2%; P=.001), which could be related to the higher percentage of patients with cABV.

As in other reported series, there was a 35.2% total decrease in the number of preferential/urgent pacemaker implantations compared with 2019 (568 vs 877; P < .001).

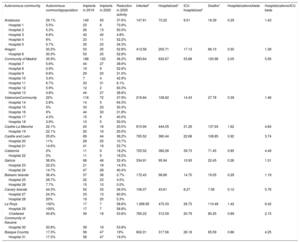

All autonomous communities analyzed except the Balearic Islands experienced a reduction in activity, although to a varying degree (table 2). Through the use of data from official reports of the Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Statistics, an attempt was made to explain this variability by relating it to the impact of the pandemic in each region. No correlations were found with the number of infected individuals in each autonomous community (Spearman ρ=0.162; P=.596), the number persons hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19 (ρ=–0.028; P=.929), the number of persons admitted to the ICU (ρ=–0.217; P=.476), or the number of deaths due to this disease (ρ=0.105; P=.734) per 100 000 population. Nor was there an association between the decrease in pacemaker procedures and saturation of the health system in each region, measured by the following ratios: number of COVID-19 hospitalizations/beds available at baseline (ρ=0.080; P=.796), or the number of COVID-19 ICU hospitalizations/ICU beds available at baseline (ρ=0.061; P=.844). As mentioned, the aim of this study was to obtain a general view of what happened during the first wave of the pandemic in Spain. However, to properly interpret these results it is important to note that the information collected covered only 40% of the provinces, and the population at risk included in the analysis represented an average of 33.3% of the total in each autonomous community (table 2). This was an important limitation for establishing a relationship between the impact of the pandemic and the reduction in activity.

Relationship between the number of implant procedures during the 2019 and 2020 study periods and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, by autonomous community

| Autonomous community | Autonomous communitypopulation | Implants in 2019 | Implants in 2020 | Reduction in 2020 activity | Infected* | Hospitalized* | ICU hospitalized* | Deaths* | Hospitalizations/beds | Hospitalizations/ICU beds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 29.1% | 149 | 93 | 37.6% | 147.61 | 73.22 | 9.01 | 16.39 | 0.29 | 1.43 |

| Hospital 1 | 5.5% | 23 | 6 | 73.9% | ||||||

| Hospital 2 | 5.3% | 26 | 13 | 50.0% | ||||||

| Hospital 3 | 6.6% | 42 | 40 | 4.8% | ||||||

| Hospital 4 | 6% | 23 | 11 | 52.2% | ||||||

| Hospital 5 | 5.7% | 35 | 23 | 34.3% | ||||||

| Aragon | 30.3% | 53 | 25 | 52.8% | 413.56 | 200.71 | 17.13 | 66.10 | 0.50 | 1.38 |

| Hospital 6 | 30.3% | 53 | 25 | 52.8% | ||||||

| Community of Madrid | 35.9% | 188 | 120 | 36.2% | 993.64 | 632.67 | 53.68 | 120.96 | 2.05 | 5.95 |

| Hospital 7 | 5.6% | 44 | 27 | 38.6% | ||||||

| Hospital 8 | 2.9% | 19 | 9 | 52.6% | ||||||

| Hospital 9 | 6.6% | 29 | 20 | 31.0% | ||||||

| Hospital 10 | 3.4% | 7 | 4 | 42.9% | ||||||

| Hospital 11 | 6.7% | 33 | 31 | 6.1% | ||||||

| Hospital 12 | 5.9% | 12 | 2 | 83.3% | ||||||

| Hospital 13 | 4.8% | 44 | 27 | 38.6% | ||||||

| ValencianCommunity | 22% | 116 | 72 | 37.9% | 216.84 | 108.62 | 14.43 | 27.78 | 0.39 | 1.46 |

| Hospital 14 | 2.8% | 14 | 5 | 64.3% | ||||||

| Hospital 15 | 5% | 33 | 23 | 30.3% | ||||||

| Hospital 16 | 6% | 44 | 30 | 31.8% | ||||||

| Hospital 17 | 4.3% | 15 | 9 | 40.0% | ||||||

| Hospital 18 | 3.9% | 10 | 5 | 50.0% | ||||||

| Castile-La Mancha | 22.1% | 20 | 16 | 20.0% | 815.94 | 444.05 | 31.29 | 137.93 | 1.62 | 4.84 |

| Hospital 19 | 22.1% | 20 | 16 | 20.0% | ||||||

| Castile and León | 25.6% | 69 | 44 | 36.2% | 765.52 | 360.44 | 22.68 | 108.85 | 0.92 | 3.74 |

| Hospital 20 | 11% | 28 | 25 | 10.7% | ||||||

| Hospital 21 | 14.6% | 41 | 19 | 53.7% | ||||||

| Catalonia | 2% | 11 | 9 | 18.2% | 725.52 | 382.26 | 39.73 | 71.45 | 0.85 | 4.49 |

| Hospital 22 | 2% | 11 | 9 | 18.2% | ||||||

| Galicia | 36.9% | 68 | 46 | 32.4% | 334.91 | 95.94 | 10.93 | 22.45 | 0.26 | 1.31 |

| Hospital 23 | 22.2% | 21 | 18 | 14.3% | ||||||

| Hospital 24 | 14.7% | 47 | 28 | 40.4% | ||||||

| Balearic Islands | 36.4% | 37 | 38 | 2.7% | 172.43 | 98.66 | 14.70 | 19.05 | 0.29 | 1.19 |

| Hospital 25 | 28.7% | 22 | 23 | 4.5% | ||||||

| Hospital 26 | 7.7% | 15 | 15 | 0.0% | ||||||

| Canary Islands | 44.3% | 52 | 33 | 36.5% | 106.07 | 43.61 | 8.27 | 7.06 | 0.12 | 0.76 |

| Hospital 27 | 24.3% | 33 | 13 | 60.6% | ||||||

| Hospital 28 | 20% | 19 | 20 | 5.3% | ||||||

| La Rioja | 100% | 17 | 7 | 58.8% | 1.268.95 | 470.33 | 28.72 | 110.48 | 1.42 | 6.42 |

| Hospital 29 | 100% | 17 | 7 | 58.8% | ||||||

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 30.8% | 39 | 18 | 53.8% | 785.22 | 312.59 | 20.79 | 80.25 | 0.89 | 2.15 |

| Hospital 30 | 30.8% | 39 | 18 | 53.8% | ||||||

| Basque Country | 17.3% | 58 | 47 | 19% | 602.01 | 317.56 | 26.18 | 65.59 | 0.88 | 4.25 |

| Hospital 31 | 17.3% | 58 | 47 | 19.0% |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Hospitalizations/beds: number of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the community/available hospital beds in the community at baseline.

ICU hospitalizations/beds: number of COVID-19 ICU hospitalizations in the community/available ICU beds in the community.

Autonomous community population: percentage of the total population of the autonomous community attending each center.

The information used in this table was obtained from the official reports of the Ministry of Health on the course of the pandemic (report No.o 107) and the National Institute of Statistics (2019 Registry).

To summarize, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected treatment of acute heart disease, even though urgent care was guaranteed. The impact on bradyarrhythmia treatment was similar to the reported findings in ischemic heart disease and data from other countries. This difference does not seem to be related only to “competing risk”.4 It is likely that patients reduced their physical activity during the state of alarm and, therefore, their probability of experiencing symptoms. In addition, those with mild symptoms were less likely to seek medical assessment. This could explain the lower pacemaker implantation rate in asymptomatic and presyncope patients. The disruption of ambulatory activity may also have limited the possibility to attain a prompt diagnosis in patients with mild conduction disorders, which could explain the relative increase in implants for cAVB. These findings should be taken into account in future COVID-19 waves to improve organization during crises by maintaining essential outpatient activity and fostering public confidence that all areas of the health system are safe against contagion.

The coordinators of this study express their sincere gratitude to the researchers who collaborated by collecting and sending data from their respective centers: Francisco de Asís Díaz Cortegana, Javier García Seara, Julia Martínez Solé, Pablo Ávila Alonso, Luis Borrego Bernanbé, José María González Rebollo, Ernesto Díaz Infante, Óscar Alcalde Rodríguez, Josep Navarro Manchón, Francisco Javier García Fernández, José Manuel Rubio Campal, Luis Álvarez Acosta, María del Carmen Expósito Pineda, Rosa Macías-Ruíz, Pilar Cabanas Grandío, Rubén Juárez Prera, Miguel Ángel Arias, Pablo Moriña Vázquez, Tomás Ripoll-Vera, Marta Pombo Jiménez, Fernando Cabestrero de Diego, Diego Lorente Carreño, Vicente Bertomeu González, Rafael Raso Raso, Pau Alonso Fernández and Jorge Toquero Ramos.