The objective was to analyze the characteristics and prognostic factors of in-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest in Spain.

MethodsA prospective observational study was performed to examine in-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest. Two hundred children were studied, aged between 1 month and 18 years, with in-hospital cardiac arrest. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the influence of each factor on survival to hospital discharge.

ResultsReturn of spontaneous circulation was achieved in 74% of the patients and 41% survived to hospital discharge. The survival rate was significantly higher than that reported in a previous Spanish study 10 years earlier (25.9%). In the univariate analysis, the factors related to mortality were body weight higher than 10 kg; continuous infusion of vasoactive drugs prior to cardiac arrest; sepsis and neurological disorders as causes of cardiac arrest, the need for treatment with adrenaline, bicarbonate, and volume expansion, and prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In the multivariate analysis, the factors related to mortality were hematologic/oncologic diseases, continuous infusion of vasoactive drugs prior to cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation for more than 20 min, and treatment with bicarbonate and volume expansion.

ConclusionsSurvival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in children has significantly improved in recent years. The factors related to in-hospital mortality were hematologic/oncologic diseases, continuous infusion of vasoactive drugs prior to cardiac arrest, the duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and treatment with bicarbonate and volume expansion.

Keywords

In-hospital cardiac arrest (CA) is an important cause of death in children.1–14 Every 5 years, the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation updates the recommendations for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), but the effect of this technique on survival has not been clearly demonstrated.15–17 A number of studies have analyzed the causes and prognostic factors of in-hospital CA in children and have found that survival after CA varies depending on where the event took place, the underlying disease, the initial electrocardiographic rhythm, and the duration of CPR.18 However, there are few prospective studies that include a sufficiently large number of patients and have been carried out following the guidelines for Utstein style reporting,5–11 and there are no studies that analyze the changes in survival after CA in children in a single country.

The main objective of this study was to analyze the prognostic factors that influence mortality associated with in-hospital CA in children in Spain and evaluate the outcomes of CPR since the application of the 2005 recommendations, comparing them with those of a Spanish study carried out 10 years earlier.

METHODSWe performed an observational multicenter study based on an international prospective registry of in-hospital CA in children.19

The study was approved by the local ethics and research committee, and the data were collected according to the international guidelines for Utstein style reporting.20,21 The study population included children ranging in age from 1 month to 18 years who had experienced a CA during a hospital stay between December 2007 and December 2009 in 24 hospitals in 11 Spanish autonomous communities. CA was defined as the absence of a response to stimuli, apnea, the absence of signs of circulation and of palpable central pulse, or bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm) accompanied by poor perfusion in infants that required external cardiac massage and ventilation.

The following variables were recorded: age, sex, body weight, cause of CA, previous history of CA, personal and family history, previous neurological status according to the pediatric cerebral performance category (PCPC), previous functional status according to the Pediatric Overall Performance Category, type of CA, area of the hospital in which the CA took place, variables monitored, assisted ventilation, vasoactive drugs, time to initiation of CPR, initial electrocardiographic rhythm, CPR maneuvers applied, duration of CPR, and in-hospital course. The variables were defined in accordance the guidelines for Utstein style reporting.20,21

The findings were compared with those for in-hospital CA from the database of a previous Spanish study performed 10 years earlier.3

The statistical analysis was carried out using version 18.1 of the SPSS software package (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Illinois, United States) and Stata. Comparisons of the results between different groups of patients and of the findings in the present study with those of the previous report were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out and, to evaluate the influence of each factor on hospital mortality, we built a multivariate logistic regression model that included all the variables that reached statistical significance (P<.15) in the univariate analysis. A P value less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

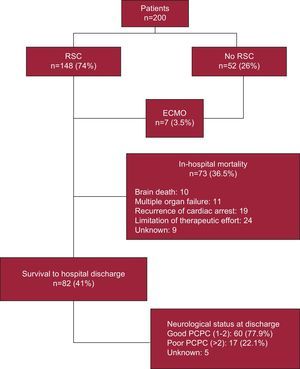

RESULTSWe studied 200 patients with in-hospital CA (54% boys). Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved in 74% of the patients; in another 7 patients (3.5%) without restoration of spontaneous circulation, recovery was achieved with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In all, 41% of the patients survived to hospital discharge; 5 of the 7 patients resuscitated by means of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survived to discharge, although 3 subsequently died. Overall, 77.9% of the survivors had a good neurological outcome (PCPC of 1 or 2). The Figure illustrates the course and outcomes in this patient population.

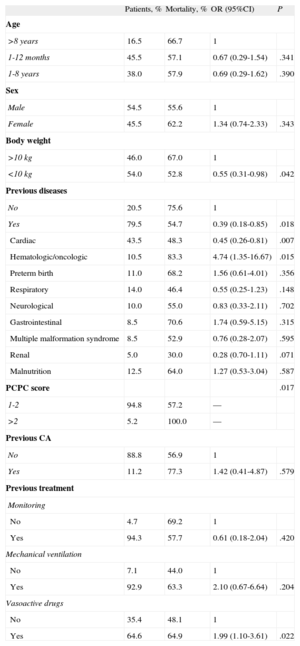

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics and the results of univariate survival analysis.

Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Prior to Cardiac Arrest Associated With Mortality (n=200)

| Patients, % | Mortality, % | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age | ||||

| >8 years | 16.5 | 66.7 | 1 | |

| 1-12 months | 45.5 | 57.1 | 0.67 (0.29-1.54) | .341 |

| 1-8 years | 38.0 | 57.9 | 0.69 (0.29-1.62) | .390 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 54.5 | 55.6 | 1 | |

| Female | 45.5 | 62.2 | 1.34 (0.74-2.33) | .343 |

| Body weight | ||||

| >10 kg | 46.0 | 67.0 | 1 | |

| <10 kg | 54.0 | 52.8 | 0.55 (0.31-0.98) | .042 |

| Previous diseases | ||||

| No | 20.5 | 75.6 | 1 | |

| Yes | 79.5 | 54.7 | 0.39 (0.18-0.85) | .018 |

| Cardiac | 43.5 | 48.3 | 0.45 (0.26-0.81) | .007 |

| Hematologic/oncologic | 10.5 | 83.3 | 4.74 (1.35-16.67) | .015 |

| Preterm birth | 11.0 | 68.2 | 1.56 (0.61-4.01) | .356 |

| Respiratory | 14.0 | 46.4 | 0.55 (0.25-1.23) | .148 |

| Neurological | 10.0 | 55.0 | 0.83 (0.33-2.11) | .702 |

| Gastrointestinal | 8.5 | 70.6 | 1.74 (0.59-5.15) | .315 |

| Multiple malformation syndrome | 8.5 | 52.9 | 0.76 (0.28-2.07) | .595 |

| Renal | 5.0 | 30.0 | 0.28 (0.70-1.11) | .071 |

| Malnutrition | 12.5 | 64.0 | 1.27 (0.53-3.04) | .587 |

| PCPC score | .017 | |||

| 1-2 | 94.8 | 57.2 | — | |

| >2 | 5.2 | 100.0 | — | |

| Previous CA | ||||

| No | 88.8 | 56.9 | 1 | |

| Yes | 11.2 | 77.3 | 1.42 (0.41-4.87) | .579 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| Monitoring | ||||

| No | 4.7 | 69.2 | 1 | |

| Yes | 94.3 | 57.7 | 0.61 (0.18-2.04) | .420 |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| No | 7.1 | 44.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 92.9 | 63.3 | 2.10 (0.67-6.64) | .204 |

| Vasoactive drugs | ||||

| No | 35.4 | 48.1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 64.6 | 64.9 | 1.99 (1.10-3.61) | .022 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CA, cardiac arrest; OR, odds ratio; PCPC, pediatric cerebral performance category.

The mean age was 47.5 months (range, 1-207 months) and the mean body weight, 16.2kg (range, 2-93kg). There were no differences in mortality related to age or sex. The mortality rate was lower among children weighing less than 10kg than among those whose weight was 10kg or over.

In all, 79.5% of the patients had underlying diseases. The mortality rate was lower in children with a history of heart disease and was higher in those with oncological diseases.

In 76.5% of the patients, the available data included functional and neurological status prior to CA, assessed using the pediatric overall performance category and PCPC scores, and 94.8% of them had good neurological status (PCPC score of 1 or 2). Mortality in the 8 patients with severe neurological disorders (previous PCPC greater than 2) was 100%, significantly higher than that of the remainder of the patient population.

In all, 11% of the patients had experienced CA previously. The mortality rate among these children was somewhat higher than that among the patients who had not, but this difference was not significant.

At the time of CA, 94.3% of the patients were being monitored, 92.9% required mechanical ventilation, and 64.6% were receiving vasoactive drugs. The mortality rate was significantly higher among the children receiving vasoactive agents.

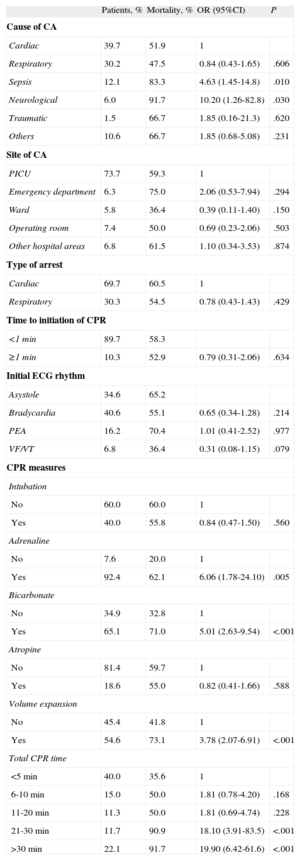

Characteristics of Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationTable 2 summarizes the univariate analysis of the relationship between the characteristics of CA and CPR and mortality.

Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Related to Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Associated With Mortality

| Patients, % | Mortality, % | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Cause of CA | ||||

| Cardiac | 39.7 | 51.9 | 1 | |

| Respiratory | 30.2 | 47.5 | 0.84 (0.43-1.65) | .606 |

| Sepsis | 12.1 | 83.3 | 4.63 (1.45-14.8) | .010 |

| Neurological | 6.0 | 91.7 | 10.20 (1.26-82.8) | .030 |

| Traumatic | 1.5 | 66.7 | 1.85 (0.16-21.3) | .620 |

| Others | 10.6 | 66.7 | 1.85 (0.68-5.08) | .231 |

| Site of CA | ||||

| PICU | 73.7 | 59.3 | 1 | |

| Emergency department | 6.3 | 75.0 | 2.06 (0.53-7.94) | .294 |

| Ward | 5.8 | 36.4 | 0.39 (0.11-1.40) | .150 |

| Operating room | 7.4 | 50.0 | 0.69 (0.23-2.06) | .503 |

| Other hospital areas | 6.8 | 61.5 | 1.10 (0.34-3.53) | .874 |

| Type of arrest | ||||

| Cardiac | 69.7 | 60.5 | 1 | |

| Respiratory | 30.3 | 54.5 | 0.78 (0.43-1.43) | .429 |

| Time to initiation of CPR | ||||

| <1 min | 89.7 | 58.3 | ||

| ≥1 min | 10.3 | 52.9 | 0.79 (0.31-2.06) | .634 |

| Initial ECG rhythm | ||||

| Asystole | 34.6 | 65.2 | ||

| Bradycardia | 40.6 | 55.1 | 0.65 (0.34-1.28) | .214 |

| PEA | 16.2 | 70.4 | 1.01 (0.41-2.52) | .977 |

| VF/VT | 6.8 | 36.4 | 0.31 (0.08-1.15) | .079 |

| CPR measures | ||||

| Intubation | ||||

| No | 60.0 | 60.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 40.0 | 55.8 | 0.84 (0.47-1.50) | .560 |

| Adrenaline | ||||

| No | 7.6 | 20.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 92.4 | 62.1 | 6.06 (1.78-24.10) | .005 |

| Bicarbonate | ||||

| No | 34.9 | 32.8 | 1 | |

| Yes | 65.1 | 71.0 | 5.01 (2.63-9.54) | <.001 |

| Atropine | ||||

| No | 81.4 | 59.7 | 1 | |

| Yes | 18.6 | 55.0 | 0.82 (0.41-1.66) | .588 |

| Volume expansion | ||||

| No | 45.4 | 41.8 | 1 | |

| Yes | 54.6 | 73.1 | 3.78 (2.07-6.91) | <.001 |

| Total CPR time | ||||

| <5 min | 40.0 | 35.6 | 1 | |

| 6-10 min | 15.0 | 50.0 | 1.81 (0.78-4.20) | .168 |

| 11-20 min | 11.3 | 50.0 | 1.81 (0.69-4.74) | .228 |

| 21-30 min | 11.7 | 90.9 | 18.10 (3.91-83.5) | <.001 |

| >30 min | 22.1 | 91.7 | 19.90 (6.42-61.6) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CA, cardiac arrest; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECG, electrocardiographic; OR, odds ratio; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; VF/VT, ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

Cardiac and respiratory diseases were the main causes of CA. However, the mortality rate was significantly higher among the patients with neurological disorders and sepsis.

The majority of CA episodes took place in the pediatric intensive care unit. The mortality rate associated with CA that occurred in the emergency department was higher than that recorded for any other area of the hospital, although the differences were not statistically significant.

There were no differences in mortality between episodes that began as respiratory arrests and those presenting as CA. Bradycardia was the most common electrocardiographic rhythm. Only 6.8% of the patients had shockable rhythms (ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia). The mortality rate among children with shockable rhythms was lower (36.4%), but the differences were not statistically significant. In 89.7% of the patient population, CPR was initiated less than 1min after the diagnosis of CA.

Mortality was significantly higher among the patients who required adrenaline, bicarbonate, and volume expansion (at least 10mL/kg during CPR). The mortality rate increased in relation to the duration of CA.

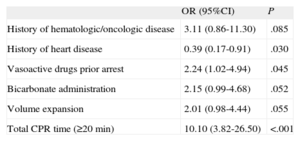

The multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3) revealed that hematologic/oncologic diseases, administration of continuous infusion of vasoactive drugs prior to the arrest, the need for bicarbonate administration, volume expansion during CPR, and CPR duration greater than 20min were risk factors associated with mortality.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Including the Factors That Influenced Mortality

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

| History of hematologic/oncologic disease | 3.11 (0.86-11.30) | .085 |

| History of heart disease | 0.39 (0.17-0.91) | .030 |

| Vasoactive drugs prior arrest | 2.24 (1.02-4.94) | .045 |

| Bicarbonate administration | 2.15 (0.99-4.68) | .052 |

| Volume expansion | 2.01 (0.98-4.44) | .055 |

| Total CPR time (≥20 min) | 10.10 (3.82-26.50) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OR, odds ratio.

Variables introduced into the model: adrenaline, bicarbonate, volume expansion, cardiopulmonary resuscitation time (>20min), body weight (<10kg), history of heart disease, history of hematologic/oncologic disease, history of respiratory disease, history of renal disease, vasoactive drugs, cause of the arrest (cardiac, respiratory, sepsis, others).

The study performed previously in Spain involved 283 patients with CA and/or respiratory arrest occurring both in hospital and out of hospital.3 One hundred thirty-five children had in-hospital CA (71.1% of them in the pediatric intensive care unit). Survival was 25.9%, with a statistically significant difference (P<.001) between both studies. Duration of CPR greater than 20min was the factor most strongly associated with mortality.3

DISCUSSIONOur study confirms that, although in-hospital CA in children is associated with a high mortality rate, survival (41%) has significantly improved in recent years.

In a previous study carried out in Spain, survival to discharge after in-hospital CA was 25.9%. This difference may be due to a number of factors. Over the past decade, there has been a considerable effort to provide training in pediatric CPR, coordinated by the Spanish Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Group, with the development of a number of courses on basic and advanced pediatric CPR.22,23 The implementation of the 2005 international recommendations may also have played a role in the improvement in survival. Although most of the participating hospitals were the same in both the first and second studies, other factors such as the organization of hospital care may have influenced these results.

The patient characteristics and the factors related to mortality in the 2 studies were very similar. In both studies, the factors most closely related to mortality were the duration of CPR and the need for measures such as adrenaline or bicarbonate administration and volume expansion.

Patient Characteristics and Clinical Status Prior to Cardiac ArrestThe mortality rate was lower among the children weighing less than 10kg compared with that in those weighing more. Other authors have found that the survival rate was higher among younger children than in older patients.10

Previous neurological status was normal in most patients. Although mortality was 100% among the children with a previous neurological disorder (PCPC greater than 2), the small number of patients makes their inclusion in statistical comparisons unviable.

In addition, the mortality among patients who received vasoactive drugs was significantly higher. This circumstance probably only reflects the fact that they were more seriously ill, an observation reported in the previous Spanish study3 and by other authors.8,11

Characteristics of Cardiac ArrestThe mortality rate was higher among patients with hematologic/oncologic diseases, a finding that had been reported in other studies.9,11

The most common causes of CA were respiratory and cardiac diseases. However, as observed in other studies, the causes most strongly associated with mortality were sepsis and neurological disorders. This finding highlights the importance of establishing measures for the early diagnosis and treatment of sepsis.21

Most of the episodes of CA occurred in the pediatric intensive care unit. The mortality associated with CA that took place in the emergency department was higher than the rates corresponding to all other areas of the hospital, although the differences were not statistically significant. For this reason, it is important that a program be developed for the prevention and treatment of CA throughout the entire hospital.24 A number of studies have demonstrated the usefulness of creating rapid response teams to improve the prevention and treatment of CA in children.25,26

Bradycardia was the most frequently recorded electrocardiographic rhythm (82.2%), coinciding with the findings reported in other studies.7,12,27 This is one of the most important differences with respect to the previous Spanish study, in which bradycardia was the initial rhythm in only 38% of patients with CA, whereas asystole was the most frequently detected rhythm.3 This finding is very important and is probably due to the fact that CA is diagnosed earlier and, thus, CPR is initiated sooner, a measure that increases the possibilities of recovery.

The percentage of children with shockable rhythms was low, a finding reported in other studies in children. For this reason, although early defibrillation improves survival, in cases of CA in children, the algorithms and management strategies should take into account mainly the treatment of nonshockable rhythms.

Characteristics of Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationIn out-of-hospital CA, the time to initiation of CPR is one of the most important prognostic factors. In contrast, in in-hospital CA, especially that occurring in the pediatric intensive care unit, CPR is begun immediately. Thus, this factor is not a highly important prognostic variable, a finding observed in our study.

The mortality rate was higher among patients who required adrenaline, bicarbonate and volume expansion, as reported in other studies.1–3,10,11,28 In recent years, some authors have pointed out that agents such as adrenaline and bicarbonate may not be useful and may even increase mortality among CA patients.29 However, there is insufficient evidence to support this hypothesis. It is unsurprising that the mortality rates among patients who require a greater number of doses of adrenaline or bicarbonate, which are only administered in situations of prolonged or refractory CA, are higher than in those who recover rapidly with massage and ventilation.

Comparative studies carried out in adults with out-of-hospital CA have found that adrenaline initially increases survival, although it has no effect on survival to hospital discharge.30,31

With respect to bicarbonate, some studies have reported a slight improvement in survival, whereas others have found no difference.32,33

The most consistent prognostic factor in our studies and in those of other authors is the relationship between the duration of CA and mortality,3 a finding that indicates that any maneuvers and treatments should be undertaken as soon as possible.

In all, 7 patients with refractory CA were resuscitated by means of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Other studies have demonstrated that this technique can be an effective rescue treatment in children with in-hospital CA refractory to CPR, but that the availability of a multidisciplinary team, specifically trained and with the necessary material prepared for immediate use, is indispensable. This framework exists in few hospitals, mainly in those with a considerable volume of cardiac surgery.34

LimitationsOur study has several limitations. Although it included a large number of hospitals from nearly every region of Spain, randomized sampling was not employed. Thus, our data cannot be extrapolated to the Spanish population as a whole. The comparison with the previous Spanish study should be analyzed with caution because there may be uncontrolled factors that could have influenced the results.

CONCLUSIONSSurvival after in-hospital CA in children has improved significantly in recent years. Training in CPR and the early diagnosis of patients before they reach asystole are probably major factors that explain this improvement. Hematologic/oncologic diseases, receiving continuous infusion of vasoactive drugs at the time of CA, the duration of CPR, and treatment with bicarbonate and volume expansion are the factors associated with mortality before hospital discharge. Comparative studies involving prospective analysis of the effect of these treatments on survival are needed.

FUNDINGThis study was supported by grant no. PI081167 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The authors wish to thank Jose María Bellón for the statistical study.

Jesús López-Herce, Jimena del Castillo, Javier Urbano, Angel Carrillo, Jose María Bellón (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), Sonia Cañadas, Pedro Dominguez (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona), Javier Pilar Orive (Hospital de Cruces, Baracaldo), Antonio Rodríguez-Núñez (Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela), María Ángeles García Teresa (Hospital Niño Jesús, Madrid), Miguel Angel Delgado (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid), Corsino Rey Galán (Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo), Jessica Ortiz Rodríguez (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona), Juan Garbayo Solana (Hospital Reina Sofía, Cordoba), Pedro Pablo Oyagüez (Complejo Asistencial de Burgos), Juan Carlos de Carlos (Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca), Custodio Calvo Macías (Hospital Carlos Haya, Malaga), Silvia Sánchez Pérez (Corporación Parc Taulí, Sabadell), Raúl Borrego Domínguez (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo), Mario José Sánchez Fernández (Hospital Josep Trueta, Girona), Cristina Molinos (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón), Concepción Goñi Orayen (Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona), Asunción Pino Vázquez (Hospital Clínico de Valladolid), Antonio de Francisco (Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona), María Elena May Llanas (Hospital Mútua de Terrassa, Terrassa), Abián Montesdeoca Melián (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife), Alfredo Reparaz (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo), Olivia Pérez Quevedo (Hospital Materno Infantil de Las Palmas, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Isabel Lucía Benítez Gómez (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville)