For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) to respond adequately to cardiac resynchronization therapy, ventricular rate should be strictly controlled to ensure the biventricular pacing rate is as close to 100% as possible.1 For this control, drugs are used that block atrioventricular (AV) conduction. When these fail, atrial node ablation is indicated, although this makes the patient pacemaker dependent. We present the case of a patient with AF with an implanted cardiac resynchronization device, in whom ivabradine was used as an alternative to AV node ablation for heart rate control.

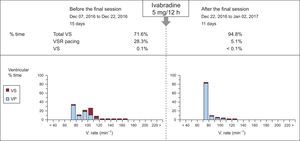

The 60-year old male patient had received a prosthetic mitral valve replacement as treatment for rheumatic mitral stenosis. He was in permanent AF with left bundle branch block. During follow-up, he showed severe systolic left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure in the absence of coronary lesions. A cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator was required. During postimplantation follow-up, 74% biventricular pacing was observed despite bisoprolol escalation to the maximum tolerated dose (5mg/12h) and device programming in VVIR mode with a minimum rate of 70 bpm. Digoxin was not administered due to a history of digitalis toxicity and renal failure. Before considering AV node ablation, we decided to try ivabradine (5mg/12h). Eleven days later, the device showed a biventricular pacing rate of 95% (Figure). In subsequent follow-up 1 month after Ivabradine initiation, pacing was maintained at 96% and therefore ablation was not required.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy device register in 2 consecutive follow-up visits (before and after initiation of oral ivabradine). The biventricular pacing rate increased from 71.6% to 94.8% after 11 days of ivabradine treatment. The rate of intrinsic ventricular rhythm (not resynchronized) is expressed as VS and VSR pacing, which corresponds to a pacing algorithm in response to the ventricular beats detected. VP pacing, ventricular pacing; VS, ventricular sensing; VSR, ventricular sensing response.

Ivabradine is an inhibitor of If current, which is the main determinant of sinus node discharge rate. The beneficial effect as a drug that slows heart rate in patients with sinus rhythm has been clearly demonstrated, both in coronary artery disease and in heart failure.

However, the sodium channel that controls If current is not located exclusively in the sinus node but is also present in high concentrations both in the compact AV node and in the posterior nodal extension.2 In addition to determining the automaticity of the subsidiary sinus node pacemaker, If current also seems to be directly related to the conduction properties of the AV node (impulse conductivity). In a clinical trial administering either an If current inhibitor (zatabradine) or placebo to patients without structural heart disease, active treatment induced a significant increase in the electrophysiological parameters of node conduction (AH interval, AV nodal effective refractory period, and Wenckebach cycle length).3 More recently, ivabradine has also been found to exercise this depressor effect on node conduction. In an animal model published by Verrier et al.,4 ivabradine administration during paced atrial rhythm led to a lengthening of the PR and AH intervals. This was more marked at rapid atrial pacing rates (use dependence) without affecting His-Purkinje system conduction or QT interval. When the drug was administered during AF, decreased ventricular response was observed without affecting the dominant atrial rates.

There is less extensive experience with ivabradine as a drug for controlling ventricular response during AF in humans. In a small case series, oral administration of ivabradine improved control of ventricular response and functional capacity in 4 of the 6 patients with rapid AF, despite treatment with beta blockers.5 More recently, a clinical trial with 32 patients with AF showed that ivabradine significantly decreased average and maximum heart rates compared with placebo, with no relevant changes in minimum heart rate after 1 month of treatment.6

Very few drugs are available to control heart rate for patients with ventricular dysfunction and therefore AV node ablation is often indicated. The safety of ivabradine, demonstrated in large clinical trials in patients at risk (coronary artery disease and heart failure), in conjunction with the lack of vasodilatory effects or myocardial contractility depression, make it a promising option for control of ventricular response in patients with AF. The inclusion of ivabradine in the therapeutic arsenal for inhibition of AV node conduction should be supported by ad hoc clinical trials.