Mechanical complications confer a dreadful prognosis in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Their prevalence and prognosis are not well-defined in the current era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) reperfusion networks. We aimed to analyze prevalence and mortality trends of post-STEMI mechanical complications over 2 decades, before and after the establishment of pPCI networks.

MethodsProspective, consecutive registry of STEMI patients within a region of 850 000 inhabitants over 2 decades: a pre-pPCI period (1990-2000) and a pPCI period (2007-2017). We analyzed the prevalence of mechanical complications, including ventricular septal rupture, papillary muscle rupture, and free wall rupture (FWR). Twenty eight-day and 1-year mortality trends were compared between the 2 studied decades.

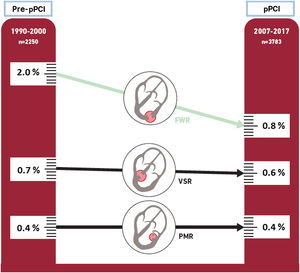

ResultsA total of 6033 STEMI patients were included (pre-pPCI period, n=2250; pPCI period, n=3783). Reperfusion was supported by thrombolysis in the pre-pPCI period (99.1%) and by pPCI in in the pPCI period (95.7%). Mechanical complications developed in 135 patients (2.2%): ventricular septal rupture in 38 patients, papillary muscle rupture in 24, and FWR in 73 patients. FWR showed a relative reduction of 60% in the pPCI period (0.8% vs 2.0%, P<.001), without significant interperiod changes in the other mechanical complications. After multivariate adjustment, FWR remained higher in the pre-pPCI period (OR, 1.93; 95%CI, 1.10-3.41; P=.023). At 28 days and 1 year, mortality showed no significant changes in all the mechanical complications studied.

ConclusionsThe establishment of regional pPCI networks has modified the landscape of mechanical complications in STEMI. FWR is less frequent in the pPCI era, likely due to reduced transmural infarcts.

Keywords

Worldwide, ischemic heart disease is the single most common cause of death.1,2 Recent studies have shown a decrease in acute and long-term mortality after ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), mostly driven by the widespread use of reperfusion therapies, mainly primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI), modern antithrombotic therapy, and secondary prevention.3,4 The main cause of in-hospital mortality after STEMI is cardiogenic shock, which is responsible for> 50% of early deaths, followed by mechanical complications (MC), which account for approximately one-third of early deaths.5–8

MC include left ventricular free wall rupture (FWR), rupture of the interventricular septum (VSR), and papillary muscle rupture (PMR).9–11 Classically, reported risk factors for the development of MC were female sex, advanced age, hypertension, higher heart rate, delayed admission, and late thrombolysis.12 FWR of the infarcted ventricle is relatively common in patients with acute postinfarct death. Several large studies have found cardiac rupture in 14% to 26% of such patients.13,14 Data reported in the late 20th century indicates that thrombolysis reduced the incidence of FWR compared with no reperfusion.15–17 Relative to VSR, its incidence was found to be low (around 0.2%) in patients receiving thrombolysis in the GUSTO-I trial,15 although an increased risk of septal rupture was observed in patients with single-vessel disease (especially of the left anterior descending artery), extensive myocardial damage, and poor septal collateral circulation.16,17 The CIVIAM, a recent Spanish registry including VSR, showed a reduction in 1-year mortality in the last few years, although the relationship with the type of reperfusion therapy or specific changes in the incidence were not completely reported.18 Finally, PMR is a life-threatening STEMI complication that accounts for approximately 5% of deaths in these patients.11

Most of the data available on MC incidence and outcomes are from classic studies using thrombolysis. The impact of pPCI on MC within STEMI networks is unclear. Accordingly, we aimed to analyze changes in incidence and mortality trends (at 28 days and 12 months) of post-STEMI MC over 2 decades: a decade before and a decade after the establishment of pPCI networks.

METHODSStudy populationThis is an analysis from the Ruti-STEMI registry,4 a prospective population-based registry of a single tertiary hospital, maintained from February 1989 through December 2017. Our hospital is the hub of 4 second-level hospitals and includes all consecutive STEMI patients serving a stable and well-defined geographical area of ∼850 000 inhabitants.

Until 2000, reperfusion therapy was mainly performed with thrombolysis. Since 2007, pPCI has been prioritized for all STEMI patients at all hours 7 days a week, a program that later crystallized in the Catalonia Codi IAM STEMI network. For the purpose of this study, we compared 2 decades, one representative of the thrombolysis era, the pre-pPCI period (1990-2000), and the other with pPCI management, or pPCI period (2007-2017). Between 2000 and 2007, thrombolysis and pPCI coexisted (the latter only during working hours), and this period was excluded from the present analysis.

Post-STEMI MC trends in prevalence, management, and mortality (at 28 days and 12 months) were analyzed. Mortality was curated from patient health records and/or by direct phone contact with patients or relatives and double-verified by the Catalan and Spanish health system databases.

All study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written consent for use of their clinical data for research purposes.

DefinitionsSTEMI definition was based on current guidelines available during the study life span.19–21 STEMI was defined as ST elevation of ≥ 1mm in at least 2 contiguous leads (in V2-V3 ≥ 2mm was required) in any location in the index or qualifying electrocardiogram.

MC was defined as any spontaneous rupture of the myocardium following STEMI. It comprises 3 types, according to the area where the myocardial rupture happens: FWR, VSR, and PMR. Confirmed FWR was defined as the occurrence of electromechanical dissociation or severe and sudden hemodynamic compromise associated with at least 1 of the following: a) pericardial effusion (> 1 cm) with intrapericardial echoes and criteria of cardiac tamponade by 2-dimensional echocardiography; b) hemopericardium by pericardiocentesis; or c) anatomic confirmation (surgical or postmortem). VSR was diagnosed by Doppler echocardiography, ventriculography, surgical closure of the ruptured site, or necropsy. PMR was diagnosed by transthoracic or transesophageal Doppler echocardiography or by anatomic confirmation (surgery or necropsy). We excluded patients with functional mitral regurgitation secondary to acute papillary muscle dysfunction but without evidence of rupture.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed using frequency and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences between groups were compared using the chi-square or Student t test. Departures from normality were evaluated using normal Q-Q plots. Multivariate analysis was performed with logistic regression, modeling with the following covariates: age, sex, hypertension, previous infarction, infarct location, and reperfusion. The assumption of linearity of continuous variables (logistic regression) was tested. Probability values <.05 from 2-sided tests were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using the software IBM Statistics SPSS 21 (IBM Corp, United States).

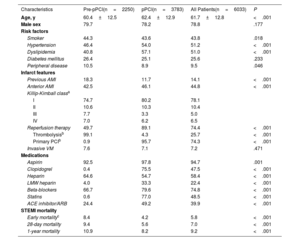

RESULTSA total of 6033 consecutive STEMI patients were included in this analysis. The mean age was 61.7 (± 12.8 years and 78.8% were men. The pre-pPCI period (1990-2000) included 2250 patients and the pPCI (2007-2017) 3783 patients. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. Patients in the pPCI period were older (62.4 vs 60.4 years, P <.001) and more often had hypertension and dyslipidemia, with lower rates of peripheral disease or previous myocardial infarction than those in the pre-pPCI period. The diagnostic criteria for hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia changed during the years of the registry, which could influence differences between periods. Patients with Killip-Kimball class III-IV declined from the pre- to the pPCI period by 35% (14.7% vs 9.5%). In the pPCI period, more than 80% of patients progressed without any signs of heart failure (Killip-Kimball class I).

Demographic characteristics, medical therapies, and management of ST elevation myocardial infarction patients in the 2 study periods

| Characteristics | Pre-pPCI(n=2250) | pPCI(n=3783) | All Patients(n=6033) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.4±12.5 | 62.4±12.9 | 61.7±12.8 | <.001 |

| Male sex | 79.7 | 78.2 | 78.8 | .177 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Smoker | 44.3 | 43.6 | 43.8 | .018 |

| Hypertension | 46.4 | 54.0 | 51.2 | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 40.8 | 57.1 | 51.0 | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26.4 | 25.1 | 25.6 | .233 |

| Peripheral disease | 10.5 | 8.9 | 9.5 | .046 |

| Infarct features | ||||

| Previous AMI | 18.3 | 11.7 | 14.1 | <.001 |

| Anterior AMI | 42.5 | 46.1 | 44.8 | <.001 |

| Killip-Kimball classa | ||||

| I | 74.7 | 80.2 | 78.1 | |

| II | 10.6 | 10.3 | 10.4 | |

| III | 7.7 | 3.3 | 5.0 | |

| IV | 7.0 | 6.2 | 6.5 | |

| Reperfusion therapy | 49.7 | 89.1 | 74.4 | <.001 |

| Thrombolysisb | 99.1 | 4.3 | 25.7 | <.001 |

| Primary PCIb | 0.9 | 95.7 | 74.3 | <.001 |

| Invasive VM | 7.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 | .471 |

| Medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 92.5 | 97.8 | 94.7 | .001 |

| Clopidogrel | 0.4 | 75.5 | 47.5 | <.001 |

| Heparin | 64.6 | 54.7 | 58.4 | <.001 |

| LMW heparin | 4.0 | 33.3 | 22.4 | <.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 66.7 | 79.6 | 74.8 | <.001 |

| Statins | 0.6 | 77.0 | 48.5 | <.001 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 24.4 | 49.2 | 39.9 | <.001 |

| STEMI mortality | ||||

| Early mortalityc | 8.4 | 4.2 | 5.8 | <.001 |

| 28-day mortality | 9.4 | 5.6 | 7.0 | <.001 |

| 1-year mortality | 10.9 | 8.2 | 9.2 | <.001 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; LMW heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Table 1 shows the medical management of the studied patients in the 2 periods. In the pPCI period, there was a significant increase in the use of antiplatelet drugs, beta-blockers, statins, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Nevertheless, key differences were found between the 2 study periods relative to the reperfusion strategy. First, reperfusion increased by ∼1.8 fold between the pre- and pPCI periods. Second, among reperfused patients, 99.1% received thrombolysis in the pre-pPCI period, whereas 95.7% received pPCI in the pPCI period.

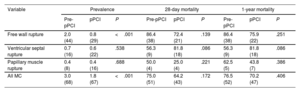

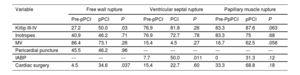

MC developed in 135 patients (2.2%), including 73 patients (1.2%) with FWR, 38 (0.6%) with VSR, and 24 (0.4%) with PMR (table 2). The prevalence of MC as a whole declined by 41% from the pre- to the pPCI period (from 3.0% to 1.8%, respectively, P <.001), mainly due to reduction in FWR. FWR showed a relative reduction of 60% in the pPCI period (2.0% vs 0.8%, P <.001), without significant inter-period changes for VSR (0.7% vs 0.6%) and PMR (0.4% both) (figure 1).

Prevalence and 28-day and 1-year mortality of post-ST-elevation myocardial infarction mechanical complications

| Variable | Prevalence | 28-day mortality | 1-year mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pPCI | pPCI | P | Pre-pPCI | pPCI | P | Pre-pPCI | pPCI | P | |

| Free wall rupture | 2.0 (44) | 0.8 (29) | <.001 | 86.4 (38) | 72.4 (21) | .139 | 86.4 (38) | 75.9 (22) | .251 |

| Ventricular septal rupture | 0.7 (16) | 0.6 (22) | .538 | 56.3 (9) | 81.8 (18) | .086 | 56.3 (9) | 81.8 (18) | .086 |

| Papillary muscle rupture | 0.4 (8) | 0.4 (16) | .688 | 50.0 (4) | 25.0 (4) | .221 | 62.5 (5) | 43.8 (7) | .386 |

| All MC | 3.0 (68) | 1.8 (67) | <.001 | 75.0 (51) | 64.2 (43) | .172 | 76.5 (52) | 70.2 (47) | .406 |

MC: mechanical complication; pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Central illustration. Prevalence of post-STEMI mechanical complications after the onset of a primary percutaneous coronary intervention network. FWR, free wall rupture; PMR, papillary muscle rupture; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; VSR, ventricular septal rupture.

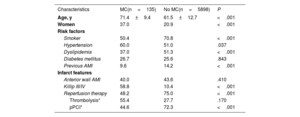

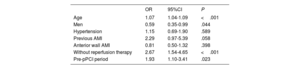

The baseline characteristics of patients with and without MC are shown in table 3. Patients with post-STEMI MC were 10 years older and were more often women and hypertensive, with a lower prevalence of prior infarct. The use of reperfusion therapy was less frequent in patients who developed a MC (48.2% vs 75.0%; P <.001). Analyses by strata showed that among patients with MC, in the pre-pPCI period, 48.5% received thrombolysis and the remaining 51.5% did not receive reperfusion treatment, whereas in the pPCI period only 4.5% received thrombolysis and 43.3% received pPCI reperfusion therapy. To compare the prevalence of FWR in the 2 periods, logistic regression analysis modeling was performed with the following covariates: age, sex, hypertension, previous myocardial infarction, infarct location and reperfusion. After multivariate adjustment, the prevalence of FWR remained higher in the first period than in the pPCI period (OR, 1.93; 95%CI, 1.10-3.41; P=.023) (table 4).

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without mechanical complications

| Characteristics | MC(n=135) | No MC(n=5898) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 71.4±9.4 | 61.5±12.7 | <.001 |

| Women | 37.0 | 20.9 | <.001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Smoker | 50.4 | 70.8 | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 60.0 | 51.0 | .037 |

| Dyslipidemia | 37.0 | 51.3 | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26.7 | 25.6 | .843 |

| Previous AMI | 9.6 | 14.2 | <.001 |

| Infarct features | |||

| Anterior wall AMI | 40.0 | 43.6 | .410 |

| Killip III/IV | 58.8 | 10.4 | <.001 |

| Reperfusion therapy | 48.2 | 75.0 | <.001 |

| Thrombolysis* | 55.4 | 27.7 | .170 |

| pPCI* | 44.6 | 72.3 | <.001 |

Logistic regression analysis for prevalence of free wall rupture between the 2 periods

| OR | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 | 1.04-1.09 | <.001 |

| Men | 0.59 | 0.35-0.99 | .044 |

| Hypertension | 1.15 | 0.69-1.90 | .589 |

| Previous AMI | 2.29 | 0.97-5.39 | .058 |

| Anterior wall AMI | 0.81 | 0.50-1.32 | .398 |

| Without reperfusion therapy | 2.67 | 1.54-4.65 | <.001 |

| Pre-pPCI period | 1.93 | 1.10-3.41 | .023 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 5 illustrates the in-hospital characteristics and management of MC during the 2 study periods. Surgical repair increased in the pPCI period in all MC (7.4% vs 37.3%; P <.001), but this difference was statistically significant only for FWR (4.5% vs 34.6%; P=.037). Overall, 28-day mortality was higher in patients with MC treated conservatively in both periods (pre-pPCI: 79.4% vs 20.0%, P=.012; pPCI: 88.1% vs 24.0%; P <.001). Lower 28-day mortality was observed in patients treated with cardiac surgery in the pPCI period for FWR (90.0% vs 33.3%; P <.004) and PMR (75.0% vs 8.3%; P=.027), with no significant differences in either the pre-pPCI period or in VSR. The use of pericardial puncture in patients with FWR was similar in both periods (∼45% of patients). The use of intra-aortic balloon pump was limited in the pre-pPCI period, but was used in half of the patients with VSR and in one-third of those with PMR in the pPCI period.

In-hospital characteristics and management of mechanical complications

| Variable | Free wall rupture | Ventricular septal rupture | Papillary muscle rupture | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pPCI | pPCI | P | Pre-pPCI | PCI | P | Pre-PpPCI | pPCI | P | |

| Killip III-IV | 27.2 | 50.0 | .03 | 76.9 | 81.8 | .26 | 83.3 | 87.6 | .063 |

| Inotropes | 40.9 | 46.2 | .71 | 76.9 | 72.7 | .78 | 83.3 | 75 | .68 |

| MV | 86.4 | 73.1 | .26 | 15.4 | 4.5 | .27 | 16.7 | 62.5 | .056 |

| Pericardial puncture | 45.5 | 46.2 | .96 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| IABP | --- | --- | --- | 7.7 | 50.0 | .011 | 0 | 31.3 | .12 |

| Cardiac surgery | 4.5 | 34.6 | .037 | 15.4 | 22.7 | .60 | 33.3 | 68.8 | .18 |

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MV, mechanic ventilation; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as percentages.

The 28-day mortality of all STEMI patients showed a relative reduction of 40% in the pPCI period (9.4% vs 5.6%; P <.001). Nevertheless, there were no significant changes in MC mortality as a whole, although a trend was observed for PMR (table 2).

One-year mortality of all STEMI patients showed a relative reduction of 25% (10.9% vs 8.2%; P <.001) in the pPCI period. No relevant changes were found in PMR (62.5% vs 43.8%; P=.386), VSR (56.3% vs 81.8%; P=.086) or FWR (86.4% vs 75.9%; P=.251) between the 2 periods (table 2).

DISCUSSIONThe present study reports a large series of post-STEMI MC spanning over 2 decades before (pre-pPCI: 1990-2000) and after the implementation of a pPCI reperfusion network (post-pPCI: 2007-2017). Several findings may be highlighted. First, overall STEMI mortality showed a dramatic reduction both at 28 days and at 12 months. These data are in agreement with reports from other European regional networks.22,23 Second, the development of post-STEMI MC declined in the pPCI period, mainly driven by a reduction in FWR (figure 1). Third, short-term mortality related to the studied MC did not significantly benefit from more aggressive management with pPCI and cardiac surgery.

In this study, FWR was the only MC that showed a significant decline in prevalence with pPCI over thrombolysis. Early studies found a decrease in the prevalence of FWR with the early administration of fibrinolysis over no reperfusion, with the caveat that late fibrinolysis increased the rate of FWR.24–26 This latter association was speculated to be due to a major increase in the rate of myocardial hemorrhage. More recently, Puerto et al.27 reported MC in a cohort of elderly STEMI patients with mixed used of thrombolysis and pPCI and identified a 48% relative reduction in the incidence of FWR. Here, we found a 60% relative reduction in FWR in the pPCI decade with universal use of pPCI compared with thrombolysis. In our series, most patients in both periods obtained the benefit of reperfusion, which confers restoration of microvascular perfusion, limits the size of the myocardial infarction and the proportion of patients with transmural infarction, and favors remodeling of the left ventricle. Nevertheless, there are several possible explanations for the reduced prevalence of FWR in the pPCI period. First, the efficacy of thrombolysis to achieve TIMI grade 3 flow decreases when time to treatment increases, whereas pPCI has been shown to achieve infarct-related artery patency in> 90% of patients regardless of prehospital delays.28 Accordingly, the increased patency rate associated with pPCI may result in greater myocardial salvage and a reduced area of transmural infarction. Second, animal studies have demonstrated that there is a greater amount of myocardial edema, hemorrhage and injury after reperfusion with thrombolytic therapy than with reperfusion by pPCI.29

There are few reports on the prevalence of VSR, as most studies combine FWR and VSR in the same category under the term “cardiac rupture”12,30 due to the low rate of VSR. Early registries including information on the trend in VSR showed a reduction in prevalence with thrombolysis compared with no reperfusion (0.2%-0.3% vs 1%-2%).15,31–33 In these studies, a very low rate of pPCI was observed: in the GUSTO-1 trial15 all patients received thrombolysis, in the MIDAS registry31 19% of patients were reperfused with pPCI, and in the GRACE registry32 38% of patients were reperfused with pPCI. The more contemporary APEX-AMI study,33 with a pPCI rate of 94%, found an incidence of VSR of 0.17%, similar to previous data with thrombolysis. Collectively, these data indicate that the incidence of VSR has declined with the use of reperfusion therapies, although the widespread use of pPCI has failed to reduce this complication compared with thrombolysis, in line with the findings reported here.

Several factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of VSR. At the biomolecular level, in the context of reperfusion injury, VSR autopsy data reveal the presence of a myocardial hemorrhage in 83% of patients treated with pPCI, in 71% of patients who received fibrinolysis, and in 18% of patients without reperfusion therapy.34 Previous studies have demonstrated that myocardial hemorrhage can create dissections in the infarcted myocardium and delay the healing process. At the biophysical level, it is known that the distribution of the mechanical load in the septum differs from that in the anterior free wall, which could increase the stress on the infarcted area in the interventricular septum. Although in-hospital prognosis is still ominous, the management with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in selective patients could be an option to improve prognosis. 18,35

The prevalence of PMR reported in the literature is so low that addressing PMR prevalence trends with management changes remains elusive. Here we did not observe changes in PMR with thrombolysis or pPCI. This finding could be due to a very low prevalence of PMR and that we only included confirmed papillary muscle ruptures after ruling out acute papillary muscle dysfunction, since, in the absence of rupture, conservative medical management is the best option with favorable outcome. Despite stable PMR prevalence rates in the 2 study periods, pPCI together with a broader use of intra-aortic balloon pumps and cardiac surgery tend to improve survival at 12 months of follow-up.

The natural history of post-STEMI MC is catastrophic, and urgent surgical repair provides the best chance of survival in patients with MC. The present study shows increasing use of emergent surgery in the pPCI period, together with better medical management, but nonetheless the survival of these patients at 28 days and 12 months remains poor. Accordingly, there is an unmet need in the management of post-STEMI patients with MC. On the one hand, preventing reperfusion injury might be a novel target in future adjunctive STEMI treatment to reduce inflammation and its associated hemorrhage.36 On the other hand, mechanical circulatory support, including ECMO, as a bridge to surgery, is being evaluated.35 Such circulatory support could improve patients’ hemodynamic status, allowing end-organ recovery for a few days before the surgical repair. The dark side of this is that VA-ECMO should not be extended more than 4 to 5 days to prevent its hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications.

Study limitationsThis study is not without limitations. It is an observational study, and therefore no causal relationships can be inferred. Despite being a single-center study based on a database designed and completed prospectively (the Ruti-STEMI registry),4 our ICCU is the reference for acute cardiac care of patients in a wide area, with several community hospitals as a hub-and-spoke model. As such, this report provides epidemiological data on post-STEMI MC over 2 decades in a Mediterranean geographic area of ∼850 000 inhabitants. The diagnostic criteria of acute myocardial infarction changed during the study period, especially due to the biochemical confirmation of myocardial infarction (CPK, CPK-MB, troponins and ultrasensitive troponins), which allow the detection of smaller infarcts. This fact could be very important in non-STEMI patients. In our STEMI registry, with very clear electrocardiogram criteria, this may not be as relevant. We only included MC with a definitive diagnosis. Because of the period of the study and emergency situations, no MC was diagnosed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging because these techniques were not available. These factors could have led to a small underestimation of MCs. Finally, none of the MCs reported here received mechanical circulatory support, as it was not available until more recently.

CONCLUSIONSTwo decades were examined to better understand prevalence trends and outcomes of post-STEMI MC. The establishment of regional pPCI networks has modified the landscape of MC in STEMI. Relative to the pre-pPCI period, FWR declined by 60% in the pPCI era, likely due to greater myocardial salvage and to pPCI reducing the area of transmural infarction. The prevalence of VSR and PMR remained unchanged in the 2 decades studied. Despite increasing use of emergent surgery in the pPCI period, 28-day and 12-month mortality remain exceedingly high. Adjunctive cardioprotection against reperfusion injury and mechanical support prior to surgery require further research if we are to improve current suboptimal results.

FUNDINGNone.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors contributed to the study according to international consensus on authorship and have approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors have no relationship with industry related to this paper, and no disclosures.

- -

Most of the available data on the incidence and prognosis of post-STEMI MC come from classic studies that use thrombolysis as the only reperfusion or as the main method of reperfusion. These studies showed decreased FWR only with early administration of thrombolysis.

- -

As the use of primary angioplasty has increased, the incidence of MC in patients with STEMI decreased over the past decade, primarily due to a reduction in FWR. However, the short-term prognosis of MC remains poor. More research is needed to improve MC outcomes in STEMI patients. Cardioprotection against reperfusion injury and mechanical support should be studied to try to improve the current suboptimal results.

.