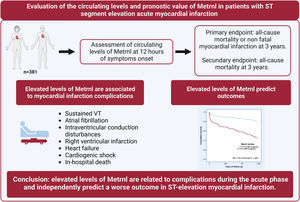

Meteorin-like protein (Metrnl) is a cytokine involved in the attenuation of inflammation. In patients with heart failure, high levels of this biomarker are associated with a worse outcome. In this study, we evaluated the circulating levels and prognostic value of Metrnl in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

MethodsWe enrolled STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulating Metrnl levels were measured in peripheral blood 12hours after symptom onset. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) at 3 years.

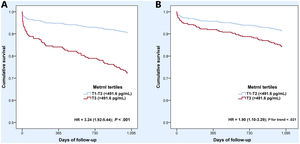

ResultsWe studied 381 patients (mean age 61 years, 21% female, 8% Killip class III/IV). Metrnl levels were associated with age, cardiovascular risk factors and the extent of coronary artery disease, as well as with STEMI complications, particularly heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Multivariable Cox regression analysis revealed that Metrnl independently predicted all-cause death or nonfatal MI at 3 years (HR, 1.86; 95%CI, 1.23-2.81; P=.003). Moreover, patients in the highest tertile (> 491.6 pg/mL) were at higher risk for the composite endpoint than those in the lowest tertiles (HR, 3.24; 95%CI, 1.92-5.44; P <.001), even after adjustment by age, diabetes mellitus, cardiac arrest, Killip-Kimball III/IV class, left ventricular ejection fraction, and creatinine clearance (HR, 1.90; 95%CI, 1.10-3.29; P=.021).

ConclusionsCirculating Metrnl levels are associated with complications during the acute phase of STEMI and independently predict a worse outcome in these patients.

Keywords

Outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have considerably improved over the last few decades, mainly as a result of the widespread use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and evidence-based treatments.1,2 However, patients still face a substantial risk of death and further cardiovascular events, in both the short- and long term. Thus, there is a need to optimize early risk stratification and identify new therapeutic targets.

Meteorin-like (Metrnl) is a secreted protein expressed by multiple tissues.3 This protein was first identified as a hormone produced by skeletal muscle and adipose tissue upon stimulation by exercise and exposure to cold, respectively, stimulating energy expenditure and attenuating inflammation and insulin resistance.4,5 Therefore, it is not surprising that it has been reported to be involved in diseases like obesity6 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).7 Preclinical studies also showed that Metrnl is produced by cardiomyocytes after cardiac injury. In a rodent model of cardiac hypertrophy, lack of Metrnl was associated with left ventricular dysfunction and enhanced interstitial fibrosis together with reduced expression of fatty acid oxidation genes and anti-inflammatory type 2 cytokines signalling components, while its overexpression prevents the development of cardiac remodelling.8 Very recently, Reboll et al.9 have shown that Metrnl is a driver of postinfarction angiogenesis. All these data point to a prominent protective role of Metrnl in the myocardium. In addition, Metrnl has also been associated with inflammatory diseases and is strongly induced in activated macropahges.10 Finally, we previously reported that Metrnl is a new prognostic biomarker in heart failure (HF) patients.8

The aim of the present study was to evaluate circulating Metrnl levels in the acute phase of STEMI treated by primary PCI and to assess its predictive value for adverse events.

METHODSStudy design and populationIn this prospective observational study, we enrolled patients with STEMI who were admitted to a tertiary university center within a primary PCI network from February 2011 to January 2016. STEMI was diagnosed and managed according to contemporary guidelines.11,12 Baseline demographics and clinical data were recorded during hospital admission in a database. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed before discharge with echocardiography using the Simpson method.

The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (reference EO-11-061) and patients or their representatives provided written informed consent.

Measurement and laboratory dataBlood samples were obtained by venepuncture 12hours after symptom onset. Samples were processed in a central laboratory for biomarker measurements. Serum was obtained by centrifugation and stored at−80°C until assayed.

Metrnl was measured by Human Meteorin-like/METRNL DuoSet ELISA (R&D Systems, United States; reference DY7867-05, lot P100731) (n=381) using spectrophotometry immunoassay according to the manufacturers’ protocols; the assay range was 15.6 to 1000 pg/mL. High-sensitivity troponin T (hs-Troponin T; n=354) and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP; n=318) were measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (Troponin T hs13 and Elecsys proBNP,14 Roche Diagnostics, Germany) with a Modular Analytics E170 system (Roche Diagnostics).

All other laboratory values (hemoglobin, creatinine, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and creatine kinase-MB) were measured at the time of admission.

Study outcomes and follow-upThe primary outcome was the composite of all-cause mortality or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) at 3 years. For patients with recurrent events, the time to the first event was recorded. The secondary outcome was all-cause mortality at 3 years. Outcome events were adjudicated based on electronic clinical records and/or directly contacting patients or relatives by telephone.

Statistical analysesCategorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range], according to normal or nonnormal data distribution. Departures from normality were evaluated using normal QQ-plots. Between-group comparisons were performed with the chi-square and Fisher test for categorical variables, and the Student t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Correlations between Metrnl levels and other continuous variables were performed using the Pearson or Spearman method, as appropriate.

Survival analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards models (using the backward stepwise method) after assessment of proportional assumptions. Nonnormally distributed variables were log2-transformed prior to analyses. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) are reported. Multivariate models included major outcome predictors according to prior knowledge15,16 which, in turn, were statistically significant (P <.05) on univariate analysis, avoiding overfitting. The following variables were incorporated into the regression model for the primary outcome: Metrnl levels, age, diabetes mellitus, cardiac arrest, Killip-Kimball class III/IV, LVEF, and creatinine clearance on admission estimated from the Cockroft–Gault formula. Similarly, the model for secondary outcome included Metrnl levels, age, cardiac arrest, Killip-Kimball class III/IV, and LVEF. In a sensitivity analysis, models that included hs-troponin T and NT-proBNP were run for both endpoints. The improvement in discrimination when adding Metrnl to the clinical models was assessed by comparing the resulting Harrell c-indexes. Cox survival curves were performed to depict how the occurrence of the primary endpoint was related to the distribution of Metrnl levels over time.

Differences were considered statistically significant at P <.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, United States) and STATA V.15.1 software (StataCorp., United States).

RESULTSPatient characteristicsA total of 381 patients were enrolled during the study period (table 1). The mean age was 61.4±13.0 years, 21% were women, and 43% had an anterior MI. Killip-Kimball class III to IV was present in 8% patients and 97% were treated with successful primary PCI at a median time of 180minutes from symptom onset.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to median circulating Metrnl levels 12hours after STEMI onset

| Variable | All patients (N=381) | Metrnl <413.2 pg/mL | Metrnl >413.2 pg/mL | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 61.4±13.0 | 57.2±12.3 | 65.6±12.3 | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 80 (21.0) | 40 (21.1) | 40 (20.9) | .979 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.0 [24.8-29.8] | 27.3 [25.0-29.8] | 26.6 [24.6-29.9] | .197 |

| History | ||||

| Smoking | .022 | |||

| Never | 91 (23.9) | 41 (21.6) | 50 (26.2) | |

| Former | 104 (27.3) | 43 (22.6) | 61 (31.9) | |

| Active | 186 (48.8) | 106 (55.8) | 80 (41.9) | |

| Hypertension | 203 (53.3) | 82 (43.2) | 121 (63.4) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99 (26.0) | 40 (21.1) | 59 (30.9) | .029 |

| Diabetes mellitus | .061 | |||

| No | 282 (74.0) | 150 (78.9) | 132 (69.1) | |

| Noninsulin treatment | 64 (16.8) | 28 (14.7) | 36 (18.8) | |

| Insulin treatment | 35 (9.2) | 12 (6.3) | 23 (12.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 202 (53.0) | 88 (46.3) | 114 (59.7) | .009 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20 (5.2) | 8 (4.2) | 12 (6.3) | .365 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 21 (5.5) | 7 (3.7) | 14 (7.3) | .119 |

| End-stage chronic kidney disease | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | .317 |

| Previous heart failure | 3 (0.8) | 0 | 3 (1.6) | .083 |

| Previous MI | 35 (9.2) | 13 (6.8) | 22 (11.5) | .114 |

| Previous PCI | 32 (8.4) | 9 (4.7) | 23 (12.0) | .010 |

| Previous CABG | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | .318 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| GRACE score | 148.9±39.3 | 135.6±27.1 | 162.2±44.7 | <.001 |

| Anterior infarct location | 163 (42.8) | 107 (56.3) | 111 (58.1) | .723 |

| Killip-Kimball class | <.001 | |||

| I | 311 (81.6) | 169 (88.9) | 142 (74.3) | |

| II | 39 (10.2) | 16 (8.4) | 23 (12.0) | |

| III | 7 (1.8) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | |

| IV | 24 (6.3) | 1 (0.5) | 23 (12.0) | |

| Coronary angiography | 380 (99.7) | |||

| Main epicardial coronary arteries ≥70% stenosis | .011 | |||

| 1 | 192 (50.5) | 97 (51.1) | 95 (50.0) | |

| 2 | 111 (29.2) | 65 (34.2) | 46 (24.2) | |

| 3 | 77 (20.3) | 28 (14.7) | 49 (25.8) | |

| Left main ≥ 50% stenosis | 15 (3.9) | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.8) | .065 |

| Successful primary PCI | 369 (96.9) | |||

| Symptom onset-to-balloon, min | 180 [123-295] | 184 [130-295] | 179 [117-299] | .839 |

| Staged PCI | 34 (8.9) | |||

| Staged CABG | 2 (0.5) | |||

| LVEF, % | 51.0±10.7 | 51.6±9.9 | 50.4±11.4 | .246 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| Hemoglobin on admission, g/dL | 13.0±1.8 | 13.3±1.6 | 12.7±2.0 | .001 |

| Creatinine clearance on admission, mL/min* | 89.2±37.7 | 103.0±37.0 | 75.5±33.2 | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 175.8±40.1 | 183.3±38.0 | 168.4±41.0 | <.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 43.2±11.3 | 42.6±10.4 | 43.7±12.0 | .379 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 105.0±34.9 | 110.6±33.9 | 99.5±35.1 | .003 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 112 [83-158] | 121 [88-168] | 106 [81-144] | .007 |

| CK-MB peak, ng/mL | 176.0 [73.2-337.1] | 176.1 [95.6-292.3] | 175.3 [67.0-372.6] | .766 |

| hs-Troponin T at 12 h, pg/mL | 3714.5 [1196.6-7115.3] | 2867.6 [1324.6-5990.2] | 4455.3 [1094.1-8474.4] | .021 |

| NT-proBNP at 12 h, pg/mL | 576.2 [254.9-1533.3] | 455.4 [230.1-1008.9] | 818.4 [343.8-2740.8] | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HR, heart rate; LDL; low density lipoprotein; LVEF; left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP; inactive proform of natriuretic peptide B; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range: Q1-Q3].

More than 98% of the patients completed the 3-year follow-up. Only 7 patients (1.8%) were lost to follow-up: 4 after discharge, who were excluded from the survival analyses, and 3 after a median follow-up of 1.7 years, who were included. At the 3-year time point, 40 patients had died, 24 had been readmitted due to MI, and 59 (16%) had had the composite endpoint (35 deaths and 24 nonfatal MI, of whom 5 subsequently died). Patients with events were older and were more likely to have a history of hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, HF, MI, or PCI. Moreover, they were reperfused later, exhibited greater disease severity (higher Killip-Kimball class and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE] score), more complications related to acute myocardial infarction (AMI), worse LVEF, lower hemoglobin and creatinine clearance values on admission, and higher NT-proBNP and Metrnl levels ().

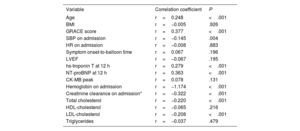

Predictors of Metrnl levelsThe median concentration of Metrnl 12hours after STEMI was 413.2 pg/mL [320.9-559.7 pg/mL]. Table 1 shows patients stratified into Metrnl above and below the median and table 2 shows Metrnl medians according to the presence of each variable. Metrnl levels were associated with the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, a history of HF and PCI, and the number of diseased coronary arteries at the time of STEMI. Furthermore, Metrnl was positively correlated with age, GRACE score and levels of hs-Troponin T and NT-proBNP, and inversely correlated with systolic blood pressure and values of hemoglobin, creatinine clearance, total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol on admission (table 3; ).

Circulating Metrnl levels 12hours after STEMI onset according to baseline characteristics

| Variable | Metrnl at 12hours, pg/mL | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | <61≥ 61 | 368.2 [297.2-471.2]483.1 [361.1-666.7] | <.001 |

| Sex | FemaleMale | 412.8 [313.8-562.7]413.2 [321.2-559.7] | .868 |

| BMI | <27.0 kg/m2≥ 27.0 kg/m2 | 438.7 [320.9-579.7]399.5 [319.6-528.9] | .293 |

| History | |||

| Smoking | NeverFormerActive | 432.3 [342.6-592.4]447.8 [339.9-630.8]389.79 [299.4-515.3] | .006 |

| Hypertension | NoYes | 378.5 [305.4-484.4]457.4 [341.1-629.5] | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | NoNoninsulin treatmentInsulin treatment | 402.6 [306.3-531.5]442.8 [339.1-631.1]466.0 [358.0-685.8] | .015 |

| Dyslipidemia | NoYes | 394.5 [307.4-519.5]443.0 [330.8-589.6] | .034 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | NoYes | 410.3 [320.9-557.0]490.3 [338.1-696.6] | .319 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | NoYes | 409.4 [319.5-549.5]526.2 [394.4-700.4] | .033 |

| End-stage chronic kidney disease | NoYes | 412.4 [320.9-557.0]594.4 [392.0-914.9] | .292 |

| Previous heart failure | NoYes | 411.3 [319.6-554.6]805.1 [771.6-870.9] | .014 |

| Previous MI | NoYes | 409.2 [320.9-559.7]472.0 [319.4-559.7] | .289 |

| Previous PCI | NoYes | 407.8 [319.4-559.7]483.5 [397.1-584.9] | .069 |

| Previous CABG | NoYes | 412.8 [320.2-558.4]828.2 [828.2-828.2] | .148 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| GRACE score | <140≥ 140 | 368.22 [290.0-463.9]483.1 [361.1-669.4] | <.001 |

| Anterior infarct location | NoYes | 409.0 [319.4-579.7]418.9 [321.2-554.2] | .944 |

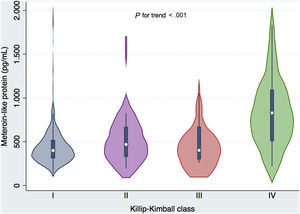

| Killip-Kimball class | IIIIIIIV | 400.0 [309.9-519.5]468.9 [327.9-669.4]402.4 [299.2-672.3]829.6 [507.3-1094.6] | <.001 |

| Main epicardial coronary arteries ≥70% stenosis | 123 | 409.4 [321.6-536.9]390.2 [302.4-515.3]483.7 [360.7-650.1] | .012 |

| Left main ≥ 50% stenosis | NoYes | 409.3 [320.9-554.2]518.7 [304.0-700.4] | .151 |

| Successful primary PCI | NoYes | 374.1 [308.0-678.6]415.5 [321.2-554.6] | .921 |

| Symptom onset-to-balloon, min | <181 min≥ 181 min | 427.7 [321.2-574.5]409.3]319.6-526.6] | .491 |

| LVEF | <53%≥ 53% | 406.5 [318.0-587.9]422.6 [327.4-539.6] | .962 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| Hemoglobin on admission | <13.2 g/dL≥ 13.2 g/dL | 450.4 [333.9-610.5]378.7 [305.8-492.9] | .001 |

| Creatinine clearance on admission* | <85.5 mL/min≥ 85.5 mL/min | 487.5 [376.1-676.2]360.7 [288.9-463.6] | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol | <171 mg/dL≥ 171 mg/dL | 447.2 [330.8-615.5]401.1 [308.6-503.4] | .026 |

| HDL-cholesterol | <42 mg/dL≥ 42 mg/dL | 416.3 [321.2-564.4]413.2 [315.0-554.2] | .381 |

| LDL-cholesterol | <100 mg/dL≥ 100 mg/dL | 456.3 [330.8-608.8]394.4 [312.6-491.1] | .007 |

| Triglycerides | <112 mg/dL≥ 112 mg/dL | 439.7 [332.2-603.6]397.3 [303.3-518.7] | .015 |

| CK-MB peak, ng/mL | <176.0 ng/mL≥ 176.0 ng/mL | 415.3 [327.5-559.7]412.4 [309.9-564.4] | .899 |

| hs-troponin T at 12 h, pg/mL | <3714.5 pg/mL≥ 3714.5 pg/mL | 392.4 [318.0-503.4]439.9 [319.6-608.8] | .025 |

| NT-proBNP at 12 h, pg/mL | <576.2 pg/mL≥ 576.2 pg/mL | 390.2 [302.5-493.6]457.4 [342.6-668.8] | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HR, heart rate; LDL, low density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, inactive proform of natriuretic peptide B; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Metrnl levels are presented as median [interquartile range: Q1-Q3]. Quantitative variables are categorized according to the median.

Correlations between circulating Metrnl levels, clinical variables, and laboratory values.

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | r=0.248 | <.001 |

| BMI | r=−0.005 | .926 |

| GRACE score | r=0.377 | <.001 |

| SBP on admission | r=−0.145 | .004 |

| HR on admission | r=−0.008 | .883 |

| Symptom onset-to-balloon time | r=0.067 | .196 |

| LVEF | r=−0.067 | .195 |

| hs-troponin T at 12 h | r=0.279 | <.001 |

| NT-proBNP at 12 h | r=0.363 | <.001 |

| CK-MB peak | r=0.078 | .131 |

| Hemoglobin on admission | r=−1.174 | <.001 |

| Creatinine clearance on admission* | r=−0.322 | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol | r=−0.220 | <.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol | r=−0.065 | .216 |

| LDL-cholesterol | r=−0.208 | <.001 |

| Triglycerides | r=−0.037 | .479 |

BMI, body mass index; CK-MB, creatine kinase-MB; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HR, heart rate; LDL, low density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, inactive proform of natriuretic peptide B; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

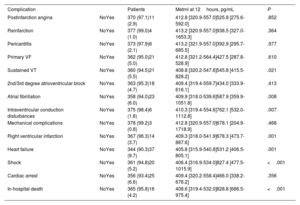

Metrnl levels were also associated with in-hospital complications of MI. Thus, concentrations were higher in patients with ventricular tachycardia (P=.021), atrial fibrillation (P=.008), intraventricular conduction disturbances (P=.007), right ventricular infarction (P=.001), HF (P=.001), shock (P <.001) and in-hospital death (P <.001) (table 4; ). There was an increasing trend for Metrnl that was related to Killip class (figure 1). Interestingly, we found no relationship between Metrnl and LVEF or other serious complications as ventricular fibrillation or cardiac arrest.

Circulating Metrnl levels at 12hours by STEMI complications

| Complication | Patients | Metrnl at 12hours, pg/mL | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postinfarction angina | NoYes | 370 (97.1)11 (2.9) | 412.8 [320.9-557.0]525.8 [275.6-592.0] | .852 |

| Reinfarction | NoYes | 377 (99.0)4 (1.0) | 413.2 [320.9-557.0]938.5 [327.0-1653.3] | .364 |

| Pericarditis | NoYes | 373 (97.9)8 (2.1) | 413.2 [321.9-557.0]392.9 [295.7-685.5] | .977 |

| Primary VF | NoYes | 362 (95.0)21 (5.0) | 412.8 [321.2-564.4]427.5 [287.8-528.9] | .610 |

| Sustained VT | NoYes | 360 (94.5)21 (5.5) | 408.8 [320.2-547.6]545.8 [415.5-828.2] | .021 |

| 2nd/3rd degree atrioventricular block | NoYes | 363 (95.3)18 (4.7) | 409.4 [319.4-559.7]434.0 [333.9-616.1] | .413 |

| Atrial fibrillation | NoYes | 358 (94.0)23 (6.0) | 409.9 [318.0-539.6]587.9 [359.9-1051.8] | .008 |

| Intraventricular conduction disturbances | NoYes | 375 (98.4)6 (1.6) | 410.3 [319.4-554.6]762.1 [532.0-1112.8] | .007 |

| Mechanical complications | NoYes | 378 (99.2)3 (0.8) | 412.8 [320.9-557.0]678.1 [204.9-1718.9] | .468 |

| Right ventricular infarction | NoYes | 367 (96.3)14 (3.7) | 409.3 [318.0-541.9]678.3 [473.7-887.6] | .001 |

| Heart failure | NoYes | 344 (90.3)37 (9.7) | 405.8 [315.9-540.8]531.2 [406.5-805.1] | .001 |

| Shock | NoYes | 361 (94.8)20 (5.2) | 406.4 [316.9-534.0]827.4 [477.5-1015.9] | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | NoYes | 356 (93.4)25 (6.6) | 409.4 [320.2-558.4]466.0 [338.2-676.2] | .356 |

| In-hospital death | NoYes | 365 (95.8)16 (4.2) | 408.6 [319.4-532.0]828.8 [686.5-975.4] | <.001 |

VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range: Q1-Q3].

Compared with participants in the 2 lowest tertiles, those in the highest tertile had a 3 times higher risk of 3-year all-cause death or nonfatal MI (HR, 3.24; 95%CI, 1.92-5.44) (figure 2). Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models (table 5) showed that Metrnl was an independent predictor of the primary endpoint (HR, 1.86; 95%CI, 1.23-2.81), together with age, the occurrence of cardiac arrest, Killip-Kimball class III or IV, and LVEF. The addition of Metrnl levels to a predictive model including these variables improved discrimination with an increase in the c-index from 0.764 (95%CI, 0.690-0.838) to 0.776 (95%CI, 0.704-0.848), although this difference was not statistically significant (P=.328), as depicted in . Further, Metrnl independently predicted 3-year all-cause mortality alone (HR, 1.84, 95%CI, 1.11-3.04). Sensitivity analyses with models that included hs-Troponin T and NT-proBNP revealed similar results for both outcomes ().

Unadjusted (A) and adjusted (B) Cox survival curves for the primary endpoint (3-year all-cause death or nonfatal myocardial infarction) according to tertiles of Metrnl levels (T3 vs T1-T2). Curves adjusted by age, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiac arrest at admission, Killip-Kimball III/IV class, left ventricular ejection fraction and creatinine clearance on admission estimated by the Cockroft-Gault formula.

Cox regression analyses of outcomes

| 3-year all-cause death or nonfatal MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Metrnl | 2.22 (1.62-3.06) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.23-2.81) | .003 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.04-1.09) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.90 (1.13-3.21) | .016 | - | - |

| Cardiac arrest | 3.72 (1.88-7.35) | <.001 | 3.48 (1.67-7.23) | .001 |

| Killip-Kimball III/IV class | 5.47 (3.04-9.85) | <.001 | 2.14 (1.08-4.23) | .028 |

| LVEF | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | .001 |

| Creatinine clearance on admission* | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) | <.001 | - | - |

| 3-year all-cause-death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Metrnl | 2.80 (1.94-4.03) | <.001 | 1.84 (1.11-3.04) | .017 |

| Age | 1.12 (1.08-1.15) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 4.28 (1.97-9.30) | <.001 | 4.73 (1.99-11.22) | <.001 |

| Killip-Kimball III/IV class | 9.42 (4.96-17.92) | <.001 | 2.59 (1.20-5.60) | .016 |

| LVEF | 0.92 (0.90-0.95) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.93-0.98) | .002 |

MI, myocardial infarction; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Analyses included only the 373 patients with complete data on all variables.

This observational study evaluated circulating Metrnl levels and their prognostic value in a cohort of unselected patients with STEMI. Higher values in the acute phase were associated with age, cardiovascular risk factors and certain MI complications, especially those related to HF but independently of LVEF. In addition, Metrnl was an independent predictor of all-cause death or nonfatal MI after a 3-year follow-up (figure 3).

Our study identified higher levels of Metrnl in older patients and in those with a history of cardiovascular risk factors and, consequently, more extensive coronary artery disease. Metrnl has been reported to be involved in metabolic disorders such as T2D and inversely related to cardiovascular risk factors.17 T2D is characterized by molecular changes in various tissues such as adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle and heart, impairing the glucose homeostasis. In adipose tissue, Metrnl stimulates energy expenditure and improves glucose tolerance by activating thermogenesis.5 Other metabolic effects have been described in skeletal muscle, increasing glucose uptake via AMPKα2 in obese or T2D mice.18 Some studies showed increased Metrnl levels in diabetic patients,7,17 while others showed the opposite results.19 These discrepancies may be due to confounding factors.20 The higher levels of Metrnl could act as a defensive response to counteract metabolic stress or resistance to Metrnl, similar to insulin or leptin resistance.17 In our study, the higher levels could also be explained because patients with diabetes, a well-known risk factor for AMI,21 could be sicker and have greater activation of other Metrnl-related pathophysiological pathways, such as inflammation. In accordance, studies in humans and rodents demonstrate that Metrnl levels are associated with HDL-cholesterol as well as being inversely associated with blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides.17,22 Such correlations were also observed in our study, although patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia showed higher Metrnl levels, probably due to an upregulated response to metabolic stress.

Given the relationship between atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome and inflammation, some authors have proposed a link between Metrnl and coronary artery disease. Thus, studies in outpatients have reported an inverse association between circulating Metrnl levels and inflammatory cytokines, insulin resistance, markers of atherosclerosis and severity of coronary artery disease.23–25 These results contrast with our findings showing that Metrnl levels increased in parallel with the number of diseased vessels. Unlike the aforementioned studies, ours included patients with AMI, a condition in which multivessel disease is known to be a predictor of mortality and the development of HF both in the short- and long-term26–29; therefore, this elevation of Metrnl levels could be explained by increased disease severity.

The second main finding of our study was the association between high Metrnl levels and STEMI severity, especially with regard to the development of HF, both left and right, and cardiogenic shock. Overall, it is recognized that the inflammatory response plays a critical role in determining AMI size and subsequent post-MI adverse left ventricular remodelling.30,31 Moreover, inflammation has been linked to disease development, progression and complications, and is predictive of poor outcomes in acute HF and cardiogenic shock independent of LVEF.32,33 Metrnl has also been associated with several inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis and rheumatoid arthritis,10 and a consistent finding is that a lack of Metrnl in mice impaired their response in a sepsis model.34 In the present study, Metrnl was determined 12hours after STEMI onset. Therefore, our data suggest that, during the proinflammatory phase, Metrnl plays a key role in modulating inflammatory response to ischemia/reperfusion injury, which could contribute to post-MI adverse left ventricular remodelling.

Finally, we identified increased Metrnl levels at the time of STEMI as an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in a model that included strong predictors such as Killip-Kimball class and LVEF. These findings are consistent with our previous study, which identified Metrnl as a prognostic biomarker in HF.8 Again, the higher Metrnl levels may be a reactive response to cardiac damage, identifying high-risk individuals. Similar observations have been made for other cardioprotective cardiokines such as ANF and FGF21.35

LimitationsThis study has some limitations. This is a single-center, observational study, although the sample size is relatively large and the follow-up was 3 years. Blood samples were drawn at a single time point and consequently we were unable to evaluate dynamic changes over time and their association with the clinical picture and outcomes.

Likewise, the study design per se does not provide sufficient data for a full understanding of the pathophysiology of Metrnl in AMI. Finally, although this study is the first to provide evidence of an association between Metrnl levels and prognosis in MI, more studies are needed to validate our results, establish their clinical usefulness, and evaluate the role of Metrnl in the acute phase of MI.

CONCLUSIONSIn patients with STEMI treated by primary PCI, circulating Metrnl levels during the first few hours are related to disease severity and are a predictor of adverse outcomes. In addition to their possible use in risk stratification, the cardioprotective and inflammatory modulator functions of Metrnl suggest the advisability of exploring its role as a new therapeutic target.

- -

Metrnl is a secreted protein with an anti-inflammatory role.

- -

Clinical studies have described the relationship between circulating Metrnl levels and metabolic diseases.

- -

Circulating Metrnl levels have a prognostic value in HF patients.

- -

Metrnl was associated with acute phase complications of STEMI.

- -

Metrnl was an independent predictor of all-cause death and nonfatal myocardial infarction after a 3-year follow-up in STEMI patients.

This work was partly supported by grants from MICINN (PID2019-110137RB-I00, PLEC2021-008194), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PIC18/00014, ICI19/00039, ICI20/00135, PI21/01700, PI21/01703), Red RICORS (PI21/01703), CIBERCV (CB16/11/00403) as a part of the Plan Nacional de I+D+I, and was cofunded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación,Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), and AGAUR (2017-SGR-483, 2019PROD00122).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSG. Ferrer-Curriu: investigation, writing original draft, revising, and editing; F. Rueda: investigation, writing original draft, revising, and editing; E. Revuelta-López: investigation, writing original draft, and funding acquisition; C. García-García: writing, revising, and editing; P. Codina: writing, revising, and editing; C. Gálvez-Montón: writing, revising, and editing; S. Roura: writing, revising, and editing, funding acquisition; A. Aimo: writing, revising, and editing; M. Emdin: writing, revising, and editing; A. Planavila: investigation, writing original draft, revising, and editing; A. Bayés-Genís: conceptualization, writing, revising, and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. G. Ferrer-Curriu and F. Rueda share authorship.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors have no disclosures.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2023.03.015