Minimally invasive approaches in less-complex cardiac procedures can avoid unpleasant cosmetic results. Moreover, surgery can be scheduled in younger patients. In previous papers, we compared submammary and midline sternotomy. We present our initial experience with an axillary, compared to submammary, approach to repair atrial septal defects under extracorporeal circulation.

Methods20 patients are included: 10 in the submammary group (7 ostium secundum, 2 sinus venosus, 1 ostium primum) and 10 in the axillary group (7 ostium secundum, 3 sinus venosus). Mean age and weight are 6.4±3.62 years (range 3-13) and 23.5±8.74 Kg (range 12-38) in the submammary group, and 5.5±2.04 years (range 3-9) and 19.7±5.88 Kg (range 14-29) in the axillary one, respectively. Muscles are spared (pectoralis in submammary and latissimus in axillary). The whole procedure (cannulation and correction) is performed through a single incision, with no side ports.

ResultsNo residual defects were found at discharge. Surgical approach maneuvers are more cumbersome through the axillary than the submammary approach. In a peer comparison, extracorporeal circulation and cross-clamp time were similar in both groups (P>.05).

Conclusions1. Axillary approach is as safe as submammary access in selected patients and for defects approached through the atrium. 2. Cosmetic result is excellent.

Keywords

Midline sternotomies are considered the usual approach for the surgical correction of congenital cardiopathies with extracorporeal circulation (ECC). In simple surgical procedures, clinical results have improved to a point where mortality and morbidity are close to zero. As a consequence, the next step in the development of this specialty is the need to reduce the cosmetic consequences resulting from conventional approaches, particularly in girls. At the same time, within the trend towards minimally invasive surgery, alternative access techniques have been developed, such as the mini-sternotomy1,2,3,4 and the sub-xiphoid,5 anterolateral,6,7,8,9,10 posterolateral,11,12,13 and recently, axillary14,15,16 approaches.

In a previous study9 we compared midline sternotomies and right anterolateral (submammary) approaches for atrial septal defect (ASD) closure, showing that no differences existed in ECC and cross-clamping times, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, or hospital discharge.9,10 In this study we compare axillary and submammary approaches; with the former the incision is hidden under the right arm, leaving the scar practically invisible.

MethodsThe study includes 20 consecutive female patients with non-complex cardiopathies, divided into 2 groups: 10 who underwent surgery through a right submammary incision (7 ASD ostium secundum, 2 ASD sinus venosus, 1 ostium primum) and 10 through the right armpit (7 ASD ostium secundum, 3 ASD sinus venosus). The mean age and weight are 6.4±3.62 years (range 3-13) and 23.5±8.74kg (range 12-38) in the submammary group, and 5.5±2.04 years (range 3-9) and 19.7±5.88kg (range 14-29) in the axillary group. Age, weight and diagnosis are shown in Table 1. During the same period, 23 patients underwent midline sternotomy with ASD as the main diagnosis. In this initial series relative contraindications were: weight below 12kg, permeable ductus arteriosus, left superior vena cava, pulmonary valve stenosis, male sex.

Table 1. Correlative List of Patients who Underwent Submammary and Axillary Approaches Detailing Age, Weight, Circulation and Cross-Clamp Times and Their Mean Values, Respectively.

| Age (years) | Weight (Kg) | ECC (min) | Cross clamp (min) | |

| Submammary | ||||

| ASD sinus venosus | 4 | 19 | 54 | 31 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 7 | 24 | 19 | 7 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 4 | 16 | 30 | 9 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 3 | 12 | 41 | 7 |

| ASD ostium primum | 3 | 16 | 62 | 36 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 4 | 18 | 30 | 8 |

| ASD sinus venosus | 8 | 28 | 69 | 34 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 12 | 35 | 35 | 14 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 6 | 29 | 29 | 13 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 13 | 38 | 35 | 17 |

| Axillary | ||||

| ASD ostium secundum | 3 | 16 | 28 | 8 |

| ASD sinus venosus | 4 | 16 | 64 | 26 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 5 | 16 | 31 | 8 |

| ASD sinus venosus | 4 | 15 | 40 | 22 |

| ASD sinus venosus | 9 | 28 | 63 | 43 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 4 | 19 | 30 | 12 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 4 | 17 | 34 | 10 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 4 | 14 | 41 | 28 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 7 | 27 | 34 | 14 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 8 | 29 | 48 | 23 |

ASD, atrial septal defect; ECC, extracorporeal circulation.

We analyzed the results in terms of ECC and cross-clamp times, residual short circuits, morbidity and the cosmetic result with both techniques. Patients and relatives could compare scars with children who underwent a midline sternotomy during their stay in the ICU and on the ward.

We carried out a descriptive analysis of epidemiological characteristics; quantitative variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation, and the discrete variables as percentages. The student's T test for independent variables was used to compare means and the Chi square test with Fischer's correction to compare discrete variables using contingency tables. A multivariate analysis was not appropriate given the small sample size (n=20) and the non-significant result of the univariate analysis. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for the hypothesis contrast tests. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software for Windows.

Surgical TechniqueThe first 9 cases included in the study underwent a submammary incision. After introducing the axillary approach in our center, the distribution criterion for the study groups was axillary incision in pre-pubertal girls and submammary incision in those with developing or developed breasts with well-defined submammary folds.

Submammary approachThe patients are placed in supine decubitus with the shoulder girdle raised to 30-45° and the right arm resting on the head. After the skin incision (Figure 1: submammary fold in teenagers, 6th space in pre-pubertal patients), the subcutaneous tissue (future mammary gland) and the pectoral muscle are dissected en bloc, creating a flap of muscle and skin. The latissimus dorsi and serratus do not have to be sectioned. The chest is accessed through the 4th intercostal space. After resection of the right lobe of the thymus, the pericardium is opened in front of the phrenic nerve and the incision is extended in the cephalad direction over the aorta and in a caudal direction to the diaphragm. Exposure of the aorta is facilitated by fixing the pericardium to the second rib and passing a tape to assist in aortic traction and manipulation.

Figure 1. Right submammary incision.

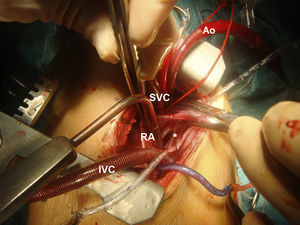

Axillary approachThe patients are placed in right lateral decubitus position, with the right arm over the head. The incision starts on the anterior axillary line at the level of the breast areola and extends to the posterior axillary line, marked by the tip of the scapula. After releasing the superficial fascia of the latissimus dorsi, its free edge is retracted dorsally without need for sectioning. The serratus is dissected and opens forward, providing access to the rib cage. Once the chest is open (4th space), the procedure is the same as that used in the submammary approach, although the surgical field is further back and deeper. Stay sutures are used on the edges of the pericardium to facilitate the approach to the heart, aorta and cavas. After these maneuvers, the right atrium is in the center of the surgical field and more accessible (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cannulation and and correction through the axillary approach, showing the arterial (Ao) and venous (superior vena cava [SVC], inferior vena cava [IVC]), right atrium (RA), cannulas and pump through the atrial septal defect (*).

CannulationThe aorta and both cavas can be cannulated directly through the thoracotomy, without the need for side ports. In all cases, the aorta was clamped and cardioplegia was administered through the aortic root. Ostium secundum type ASDs were closed using direct suture or patch closure; sinus venosus type ASDs were corrected with the double-patch technique (all associated to partial anomalous venous drainage of the right superior pulmonary vein into the superior vena cava); the ostium primum type ASDs were corrected with an autologous pericardial patch and mitral cleft. The procedure for purging air from the left side was carried out through the left atrium and the ASD closure, as well as through the aortic root.

ResultsThe basal characteristics of both groups of patients are correlated in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found in the basal characteristics of the two surgical groups (Table 2). There was not a single case of conversion to midline sternotomy. ECC times (40.4±16.09 vs 41.3±13.12min) and cross-clamping times (17.6±11.6 vs 19.4±11.18min) are identical in both groups, and no statistical significance was found, at P>0.05 (Table 2). Contingency tables were used to analyze the relationship between the surgical technique and the type of atrial septal defect. No significant differences were found (P=0.39), but given the small sample size, 20% of the items had an expected frequency below 5. Echocardiography recorded no residual defects on discharge. Four patients who underwent axillary surgery had minor complications: 1 patient who underwent surgery due to sinus venosus type ASD, with partial anomalous right pulmonary venous drainage into the superior vena cava, had transitory postoperative phrenic nerve paresis and sinus dysfunction; 2 patients had pneumothorax after removing the drainage (1 requiring further drainage); 1 girl had a seroma 3 weeks after hospital discharge.

Table 2. Differences in Extracorporeal Circulation (ECC) and Cross-Clamping Means Between Both Groups. Comparison of Basal Characteristics in Both Groups.

| Submammary | Axillary | P | |

| Age (years) | 6.40±3.62 | 5.50±2.04 | 0.37 |

| Weight (Kg) | 23.50±8.74 | 19.70±5.88 | 0.26 |

| ASD ostium secundum | 70% | 70% | 0.39 |

| ASD ostium primum | 10% | 0% | 0.39 |

| ASD sinus venosus | 20% | 30% | 0.39 |

| ECC time (min) | 40.40±16.09 | 41.30±13.12 | 0.89 |

| Cross-clamping time (min) | 17.60±11.60 | 19.40±11.18 | 0.72 |

ASD, atrial septal defect.

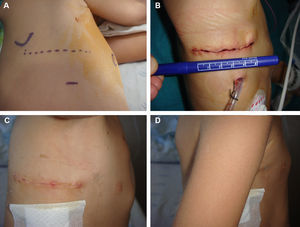

Patients and their families considered the cosmetic result to be excellent for both the axillary and submammary approaches (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A. Axillary incision, with the references for the breast areola and scapula. B. Axillary scar, about 5 cm long. C. Axillary scar, with right arm in abduction. D. Axillary scar, hidden under the right arm.

DiscussionThe surgical treatment of diverse, non-complex congenital cardiopathies is performed using midline sternotomies with excellent results. However, the cosmetic and psychological effect of the scar in groups of the population such as teenagers is acquiring increasingly greater importance. Consequently, the use of percutaneous procedures, which are less invasive and yield better cosmetic results, has increased in recent years due to the argument, among others, of not creating a scar on a patient's chest to correct a simple cardiopathy. On the other hand, recent papers show that percutaneous ASD closure can lead to both immediate and late-onset complications17 requiring rescue surgery, which involves a higher risk of mortality (5.4%) than elective surgical closure (0.36%).

For those cases that cannot benefit from percutaneous correction, minimally invasive surgical approaches have been developed that have better cosmetic results (cosmetic heart surgery), such as mini sternotomies1,2,3,4 and the sub-xiphoid,5 submammary (anterolateral),6,7,8,9,10 posterolateral11,12,13 and, more recently, axillary14,15,16 approaches. Each one has pros and cons, some of which are well known, such as the poor development of the spinal column (due to the spinal muscles being affected) or the mammary glands (posterior and anterior thoracotomies, respectively). Reviews of the anterolateral approach showed breast deformities in 20% of cases, which drove several groups to use axillary incisions,18,19 although others showed that the pectoral disinsertion technique avoided the problem of future deformities.6,8,9,20

Nowadays, the patients who undergo surgery are younger and weigh less due to earlier diagnoses and indications for surgery (given that there are asymptomatic cardiopathies, such as ASDs, which have a formal surgical indication).

The concept of cosmetic heart surgery is only appropriate when the safety of the procedure is beyond all doubt. Our working philosophy is based on approaching non-complex cardiopathies without jeopardizing the result, performing the same procedure (cannulation and correction) but using just one alternative incision, with minimal consequences. With the experience of having treated more than 80 cases with submammary incisions, we were inspired to explore a new access, another alternative to midline sternotomies. The authors’ aim is not to compare submammary and axillary sternotomies. In a previous article9 we showed the differences found between the submammary and axillary sternotomy approaches. In this paper we compare 2 minimally invasive approaches, one established in common practice and a new one. In this respect we differ from other groups, such as Schreiber et al14 (fibrillation without aortic cross-clamping), Prêtre et al15 (femoral cannulation) and Liu et al16 (vertical incision crossing Langer's lines). We intend to carry out the same surgery through another access site, without any added cost in materials or instruments, nor, of course, added risk. In this respect, it should be pointed out that this technique requires no additional instruments, does not increase costs and achieves magnificent cosmetic results.

The morbidity in our series has been minor, with 1 patient having phrenic nerve paresis and sinus dysfunction (both transitory), 2 pneumothorax cases after removing drainage, and 1 seroma at 3 weeks after hospital discharge. Cases of phrenic nerve paresis have been described with lateral accesses.21 In our case, it was probably due to excessive or inappropriate grip in the stay sutures in the pericardium, as the phrenic nerve is easily visible with lateral access and during the dissection of the surgical field it is moved to avoid injury. Similarly, sinus node dysfunction is not infrequent in the correction of sinus venosus-type ASD,22 even when this is carried out by midline sternotomy.

Both the submammary and axillary techniques conserve the muscle groups. As described above for submammary access, after the incision in the skin in the 6th intercostal space, we disinsert the pectoral muscle from the rib cage before opening the 4th space.9 According to Dieta et al,20 this maneuver, commonly used by plastic surgeons, preserves the future mammary tissue and avoids asymmetries, such as those published in other series.18,19 In the axillary approach, the incision does not exceed the anterior axillary line (Figure 3A, 3B), nor does it dissect the latissimus dorsi muscle, and thus it also conserves the future breast and the mobility of the right arm during the post-operative stages (Figure 3C, 3D).

Comparing the submammary and axillary approaches, we observed that the aorta and both cavas were deeper in the surgical field when operating with the axillary approach, which results in more complex cannulation of these blood vessels before ECC is established. However, once the aorta is on the pump and cross-clamped, access to the right atrium is excellent and the procedure can be performed comfortably without increasing ECC or cross-clamping times.9,10 No differences exist in the total surgery times between the submammary and axillary approaches, which take 30min longer than a sternotomy9 while hardly affecting the usual working dynamics in the operating room. It is important to emphasize that conversion to sternotomy was not necessary in either group. It is possible to extend the axillary incision (behind the scapula, dissecting the latissimus dorsi) and transform it into a posterolateral one11,12,13 if difficulties arise. Even so, the final scar is more hidden, under the patient's arm and towards the back. The authors suggest that it is necessary to have previous experience in ECC with anterior (submammary) and posterior approaches before performing surgical procedures through axillary access.

The complexes that a midline sternotomy can cause in teenagers should not be ignored. Body image at this age affects self-esteem, and a scar is a constant reminder of a “heart problem” for the patients, their friends and family. A submammary or axillary scar hidden under the breast or arm is more accepted than the one caused by a sternotomy, and its invisibility means it is not labeled a “heart problem” (Figure 1, Figure 3).

As with other new techniques, the initial enthusiasm brought about by positive results leads to a strong desire for its indications to be quickly extended. Although some groups have already published corrections of ASD or mitral valves through the axillary approach,23 we must continue to proceed with caution. In practice we will avoid midline sternotomies in selected cases, using the axillary approach in pre-pubertal patients and the submammary approach with adolescents and adults.14,24,25

ConclusionsIn selected pediatric patients and for defects that can be approached through the atrium, the axillary approach is as safe as submammary access. The cosmetic result is excellent, hiding the scar under the breast or in the armpit under the right arm, gaining the total approval of the patients (and relatives), and minimizing the effect on the breast.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Received 26 June 2010

Accepted 27 August 2010

Corresponding author: Sección de Cirugía Cardiaca Infantil, Hospital Materno-Infantil Carlos Haya, C/ Arroyo de los Ángeles, s/n. 29011 Málaga, Spain. giljaurena@gmail.com