Percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure is a well-established treatment for preventing ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. In standard practice, patients receive postprocedural antiplatelet therapy to prevent device-related thrombosis until device endothelialization is complete. Although the EHRA/EAPCI consensus statement recommends dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 6 months after LAA closure,1 some studies have demonstrated the safety of antiplatelet monotherapy in selected patients with a high bleeding risk.2,3 The risks associated with antiplatelet therapy, however, may be excessive in patients with a history of very severe bleeding, limiting their access to this procedure.

Whether or not antiplatelet therapy of any kind can be reasonably avoided in patients with a high bleeding risk after percutaneous LAA closure remains to be determined. The aim of this study was to describe our experience with percutaneous LAA closure without postprocedural antiplatelet therapy in patients with a history of very severe bleeding at our hospital.

Of 103 patients who underwent percutaneous LAA closure with an Amulet device (Abbott, USA), 14 (13%) were not treated with postprocedural antiplatelet therapy. These patients had a history of major bleeding (as defined by the Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis4) and a mean HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke, bleeding, labile INR, elderly, and drugs or alcohol) score of 4.6 (table 1). Six had previously experienced intracranial bleeding (3 in the context of amyloid angiopathy) and 7 had had major gastrointestinal bleeding. The other patient had had vitreous hemorrhage resulting in blindness while on anticoagulation therapy. Informed consent was duly obtained.

Transesophageal echocardiography-guided LAA closure was performed under general anesthesia with low intraprocedural doses of heparin. To enhance implantation success, measures were taken to ensure tight disc-LAA wall apposition and confirm the absence of residual leaks. Factors associated with device-related thrombosis (Table 1) were observed in just 2 patients (ventricular dysfunction in both cases). There were no complications and satisfactory LAA closure was achieved in all patients.

Baseline clinical characteristics, procedure characteristics, and follow-up events in patients who underwent percutaneous left atrial appendage closure without subsequent antiplatelet therapy

| Baseline characteristics (n=14) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 76.5±5.4 |

| Women | 4 (28.5) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 5.5±1.4 |

| HAS-BLED score | 4.6±0.9 |

| Annual risk of stroke/TIA/systemic embolism | 9.9±1.2 |

| Annual bleeding risk | 9.2±1.4 |

| Previous bleeding events | |

| Intracranial | 6 (42.8) |

| Vitreous | 1 (7.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (42.8) |

| Procedure characteristics | |

| Implantation success | 14 (100) |

| Device size, mm | 23.1±3.4 |

| Residual leaks >3mm | 0 |

| Device-related thrombosis factors | |

| Spontaneous echo contrast in left atrium | 0 |

| Severe ventricular dysfunction | 2 (14.3) |

| Deep implantation | 0 |

| Complete apposition in left atrium | 14 (100) |

| Transesophageal echocardiogram after 1-3 mo (n=10) | |

| Thrombosis | 0 |

| Residual leaks >3mm | 0 |

| Follow-up events | |

| Mean follow-up, mo | 25.2±11.3 (1-52) |

| Stroke/TIA | 0 |

| Minor bleeding | 2 |

| Sudden cardiac death | 0 |

| Sudden noncardiac death | 1 |

CHA2DS2-VASc, acronym for congestive heart failure; hypertension, age ≥ 75 years (double score), diabetes mellitus, stroke (double score) vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years and sex (female); HAS-BLED, acronym for hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke, bleeding, labile INR, elderly, and drugs or alcohol; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

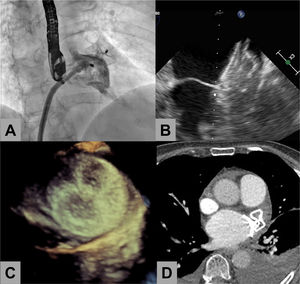

Eleven patients underwent follow-up transesophageal echocardiography 1 to 3 months after the procedure, and none of them showed device-related thrombus. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in 2 patients (both with advanced dementia) and 1 had a follow-up computed tomography chest scan (figure 1).

Percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure in a patient who did not receive subsequent antiplatelet therapy. A: angiogram during evaluation of residual leaks after device release. B: follow-up transesophageal echocardiogram at 1 month showing tight apposition and absence of leaks and thrombi at the left atrial disc. C: 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiogram showing the occluder disc 3 months after LAA closure. D: cardiac computed tomography showing good apposition and absence of thrombi.

Over a mean follow-up period of 25 months, 2 patients experienced a fall linked to an underlying neurological disorder (1 of them had associated subdural hematoma). Another patient experienced minor gastrointestinal bleeding. There were no ischemic events.

The safety of antiplatelet monotherapy after percutaneous LAA closure has been demonstrated in small case series2 and in a study of 610 patients that stratified patients according to whether they had received single or dual antiplatelet therapy after LAA closure. While the authors found no differences in the occurrence of ischemic events, they reported significantly fewer bleeding events in the patients treated with a single antiplatelet agent.3 Antiplatelet monotherapy is currently being evaluated in the STROKE-CLOSE randomized clinical trial (NCT02830152) comparing antiplatelet monotherapy and standard treatment following LAA closure in patients with a history of intracerebral hemorrhage. Antiplatelet monotherapy, however, is not without bleeding risk, as demonstrated in the AVERROES trial, in which patients treated with aspirin had similar bleeding rates to those treated with the anticoagulant apixaban.5

In the absence of device-related thrombosis factors after LAA closure in patients with a high bleeding risk, it would seem reasonable to assume that the risk of an ischemic event during follow-up (generally of little clinical significance) would be preferable to that of a potentially fatal bleeding event. Three patients in our series experienced a new bleeding event during follow-up, even though they were not on antiplatelet therapy.

Preclinical studies have shown that device endothelialization occurs within 28 to 90 days of LAA closure.6 In addition, because ischemic events are more likely to occur in the months immediately following closure, close monitoring with imaging techniques early on might help detect device-related thrombosis and enhance the overall safety of this strategy.

In conclusion, percutaneous LAA closure without subsequent antiplatelet therapy appears to be feasible in selected patients with a high risk of bleeding and a minimal risk of device-related thrombosis, although close follow-up with serial imaging is necessary. Given the small size of this series, larger studies, ideally within a clinical trial setting, and investigation of other occlusion devices are necessary to confirm these preliminary findings.

FundingNo funding relevant to this manuscript was received.

Authors’ ContributionsAll the authors contributed to this study and were involved in either managing the cases and discussing the treatment strategy (L. Unzué, E. García, M. Rodríguez del Río, F.J. Parra, R. Teijeiro-Mestre) or preparing and writing the manuscript (L. Unzué, B. Díaz-Antón). All the authors revised the paper.

Conflicts of InterestThere are no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.