The first reported case of myocarditis after administration of the BNT162b2 vaccine (BioNTech-Pfizer, Germany-United States) against COVID-19 was recently published.1

According to the Brighton Collaboration, myocarditis and pericarditis are theoretical risks of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 due to immunopathological mechanisms and should be considered adverse events of special interest, with close monitoring of their development in vaccinated people or of an increase in their incidence vs that expected.2 Multiple cases of pericarditis have been reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection,3 but there have been no published cases of pericarditis after vaccination against COVID-19.

Here, we report 2 cases of pericarditis after administration of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Both patients have consented to the publication of their clinical cases. In addition, these adverse events have been reported to the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System for Medicines for Human Use.

Case 1 concerns a 36-year-old man with a history of acute idiopathic pericarditis in 2013, who was under any routine treatment. He presented to the emergency department with crushing chest pain that began some hours before. The pain was not effort-related but increased with deep breathing and when the patient was lying down and improved when he was sitting up. The patient stated that the pain was similar to that of the previous episode of pericarditis. He had no fever and did not report any recent respiratory infections. He had no history of COVID-19. He had received the second dose of the BioNTech-Pfizer mRNA vaccine 11 days before symptom onset.

During his stay in our center, the patient was hemodynamically stable, with adequate saturation. Physical examination revealed no abnormal findings (no murmur or pericardial friction rub).

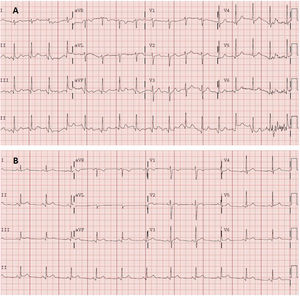

Electrocardiography (figure 1A) demonstrated sinus tachycardia with no clear signs of pericarditis. Blood tests showed leukocytosis (11.60 × 103/μL) with neutrophilia (8.7 × 103/μL), without elevated acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein, 1.80mg/L; D-dimer, 117 ng/mL). Myocardial damage markers were negative, with high-sensitivity troponin of 9 (0-72) ng/L. Chest radiography showed no pertinent findings.

A: electrocardiogram obtained in the emergency department. Sinus tachycardia at 105 bpm, normal axis (90°). Normal PR interval (120ms). Narrow QRS. Nonsignificant Q wave in the inferior wall. Without acute repolarization abnormalities. Corrected QT in the normal range. B: electrocardiogram obtained 2 days later in the cardiology clinic. Sinus rhythm at 75 bpm, normal axis. Normal PR interval (120ms), with a PR segment decrease. Narrow QRS. Concave and generalized ST-segment elevation. Corrected QT in the normal range.

The patient was discharged with clinical judgment of incipient acute pericarditis, although he met only 1 diagnostic criterion (pain with pericarditis characteristics). Given the clinical suspicion, treatment was begun with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (ibuprofen, 600mg/8h) and colchicine. The patient was evaluated in the outpatient cardiology clinic 48hours later and the diagnosis of pericarditis was confirmed after a new electrocardiogram (figure 1B) revealed PR interval shortening with incipient submillimeter, concave, and generalized ST-segment elevation that was not present on the previous electrocardiogram. Transthoracic echocardiography showed no pericardial effusion or other abnormalities. The patient exhibited a favorable clinical course, with complete cessation of the pain, and he remains asymptomatic.

Case 2 concerns an 80-year-old man with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation treated with pulmonary vein cryoablation in 2009. He was referred to the emergency department by his primary care physician after 4 days of pain localized to the left hemithorax. The pain was not effort-related and worsened with deep breathing. He had no fever and did not report recent respiratory infections. He had received the second dose of the BioNTech-Pfizer mRNA vaccine 11 days before symptom onset. He had no history of COVID-19.

The patient was hemodynamically stable, with good saturation, and with no abnormalities on physical examination (no murmur or pericardial friction rub).

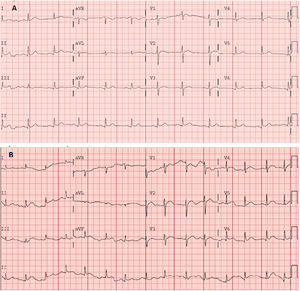

Electrocardiography (figure 2A) revealed ST-segment elevation localized to the inferior (II, III, and aVF) and lower lateral (V4-V6) walls, with decreased voltages in these leads. Blood tests showed elevated acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein, 58mg/L; D-dimer, 586 ng/mL) and a normal complete blood count. Myocardial damage markers were negative, with high-sensitivity troponin of 7 ng/L. Chest radiography showed no pertinent findings.

A: electrocardiogram obtained in the emergency department showing sinus rhythm at 75 bpm. Normal axis. Narrow QRS and ST-segment elevation in the inferolateral wall. Corrected QT in the normal range. B: electrocardiogram obtained 5 days later showing sinus rhythm at 85 bpm. Normal axis. Narrow QRS. Generalized ST-segment elevation with concave morphology. Corrected QT in the normal range.

Pericarditis was diagnosed based on the pain with pericarditis characteristics and the compatible electrocardiogram. The patient was discharged under treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and colchicine and with withdrawal of his antiplatelet regimen. The patient attended the emergency department again 5 days later with colchicine-related diarrhea; he was found to have leukocytosis (14.56 × 103/μL) with neutrophilia (12.5 × 103/μL), persistent inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein, 56.3 mg/L; fibrinogen, 736 mg/dL), and compatible electrocardiogram (figure 2B). Transthoracic echocardiography performed in the outpatient clinic showed minimal but universal pericardial effusion.

In both cases, the study was completed with postvaccination serology, which showed a positive vaccine response (antiprotein S antibodies) at 333 and 133 UA/mL, respectively, without serological evidence of previous COVID-19 infection (antinucleocapsid antibodies).

Although causality could not be established, a suspected adverse drug reaction is reasonable due to the temporal correlation (both cases occurring 11 days after the second dose), as well as the biological plausibility of an autoimmune response or a crossreaction due to molecular mimicry.4

In conclusion, we present 2 cases of pericarditis occurring after anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. We wish to highlight the importance of monitoring and documenting adverse events experienced by patients after vaccination and reporting those that are severe or unknown.5

FUNDINGNone.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSA. Ramírez-García is the main author of the text. S. Lozano Jiménez is the principal reviewer of the clinical cases. A. Ramírez-García, S. Lozano Jiménez, I. Darnaude, A. Gil Cacho, and R. Aguado-Noya attended to and diagnosed the patients. J. Segovia is the chief of the cardiology department of the hospital.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

We appreciate the approval of the patients to publish their clinical cases, as well as the help of the Pharmacovigilance Center of the Community of Madrid.