Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects approximately 1% of live newborns. Due to improvements in diagnosis and treatment, the vast majority reach adulthood. This large cohort of young adult “survivors” includes a high number of women of childbearing age.

Unfortunately, patients with CHD tend to underestimate the severity of their disease,1 which is particularly concerning in women of childbearing age. The risks of complications during pregnancy and peripartum in this population depend on the underlying defect, the extent and severity of residual lesions, and comorbidities.2 With this in mind, the clinical guidelines recommend that all women with congenital heart disease receive advice before conceiving.3

Few studies have assessed the perception of women of childbearing age with CHD regarding their heart disease and understanding of the risks,4 their desire to have children, and their contraceptive options.5 Our aim was to evaluate these key points with a detailed questionnaire.

A descriptive cross-sectional study was designed, recruiting all women aged 15 to 45 years undergoing follow-up at our adult CHD clinic. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital. The questionnaire included 19 questions for the patient and 8 for an immediate relative.

CHD was classified by severity as mild, moderate, or severe, following the recommended classification of the Sociedad Española de Pediatría Extrahospitalaria y Atención Primaria (Spanish Society of Outpatient and Primary Care Pediatrics). The cardiovascular risk of pregnancy was also classified according to the modified World Health Organization classification.3

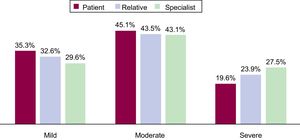

Fifty-one (75%) of the 68 women who were initially identified completed the questionnaire. The types of CHD recorded were ventricular septal defect (n=14), coarctation of the aorta (n=5), univentricular heart/Fontan circulation (n=5), bicuspid aortic valve (n=4), pulmonary stenosis (n=4), double outlet right ventricle (n=4), tetralogy of Fallot (n=3), partial atrioventricular canal (n=3), subaortic stenosis (n=3), prolapsed mitral valve (n=2), repaired patent ductus arteriosus (n=1), truncus arteriosus (n=1), congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (n=1), and ostium primum atrial septal defect (n=1). In the first part of the questionnaire, the patients were asked to rate the severity of their heart disease: 35.3% responded mild; 45.1%, moderate; and 19.6%, severe. This differed significantly (P=.001) from the opinion of the cardiologists and relatives (Figure 1).

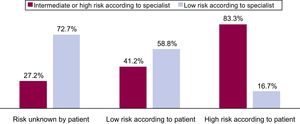

Regarding the risks of pregnancy, only 52.9% of the women reported having discussed the health risks of a potential pregnancy with their specialist. When asked to classify the risk associated with a potential pregnancy, 25.5% responded high; 33.3%, low; and 41.2% reported they did not know. Of those who said they did not know, most of the women were from the group deemed low-risk by the specialist (73%). In contrast, in the group of patients that considered pregnancy to be high-risk, the percentage considered high-risk according to the specialist was relatively high (83%) (Figure 2).

Of particular note was that 40% of the women expressed a desire to have children, their mean age being 29.6±6.4 years. Only 11 of the 51 women (21.6%) had had a previous pregnancy, and they reported 9 planned pregnancies, 1 unexpected, and 5 unwanted pregnancies that were terminated (33.3% of the total). None reported that they were using contraception when they became pregnant. Only 44% of all the patients reported having received information from their pediatrician on contraceptive methods.

One third (31.4%) of the women of childbearing age were not routinely using contraception. Condoms were the most widely used method in our sample (37.3%), followed by the oral contraceptive pill (21.6%) (7 progesterone only and 4 combined progesterone and estrogen, among which there was 1 woman from the high-risk group). Thus, 68.7% were using no contraceptive or a low-efficacy contraceptive (barrier methods).

Our results show that women of childbearing age with CHD underestimate their disease, especially those with more severe disease. Nearly half did not know the level of risk associated with pregnancy and only 1 in 4 considered it to be high-risk. Both these findings agree with the results of previous studies4 and highlight the urgent need to improve family planning programs.

Given the high percentage of women in our population who expressed a desire to have children (40%) and the lack of contraceptive information during the pediatric age, we should consider the need to involve other professionals (such as gynecologists and primary care physicians) in the preconception program for women with CHD. The inconsistent and suboptimal use of contraception reported in our study, along with the high percentage of terminated pregnancies (33%), all due to insufficient family planning, reflects once more the need to improve the sexual health education on effective contraceptive methods provided to these women.

The main limitations of the study are its cross-sectional design and the small sample size, although this is similar to previous published studies in other countries. Nonetheless, these results from a regional referral center for CHD could be extrapolated to other hospitals with similar characteristics, and the questionnaire was designed appropriately, in keeping with previous studies in similar populations.6