An exercise stress echocardiogram (ESE) offers 2 sets of data that can predict all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality: echocardiographic (ECG) images and exercise stress data.1,2

Information is lacking, however, on the relative contribution of these 2 data sources to the prediction of different types of death, particularly in women, who have a higher life expectancy and have been studied less than men. The aim of this study was to measure the ability of ESE images and exercise data to predict different causes of death in women.

We studied 4714 women (mean±standard deviation [SD] age, 64±11 years) who underwent an ESE to investigate suspected coronary artery disease or evaluate this disease between 1995 and 2014. The Bruce treadmill exercise protocol was used in 87% of patients. Workload in metabolic equivalents (METs) was derived from the characteristics of the protocol. A person who reached 10 METs was considered to have good functional capacity. ECG images were acquired at peak stress.1,2 The wall motion score index and changes to this index with exercise were calculated. Ischemia was defined as new or worsening wall motion abnormalities with exercise. All patients gave their written informed consent.

The events analyzed were cardiovascular (CV) mortality, cancer-specific (CA) mortality, and mortality due to other causes (non-CV [NCV] and non-CA [non-CA] mortality). CV death included cardiac death, death due to stroke, and death due to atherosclerosis complications. Cardiac death was defined as death due to myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, fatal arrhythmias, or cardiac arrest, or sudden, unexpected, and unexplained death. NCV-NCA death included death due to infectious, neurological, pulmonary, or liver disease, kidney or multiorgan failure, noncardiac surgery, accident, trauma, suicide, other noncardiac deaths, and deaths with an unknown/unobtainable cause. The above information was obtained from the Galician Death Registry. Continuous variables are reported as mean±SD and differences between groups were measured by analysis of variance. Univariate and multivariate analyses of causes of death were performed.

Clinical and ESE variables stratified by METs are shown in table 1. Over a follow-up period of 4.7±4.7 years [interquartile range, 0.04-8.0 years], there were 345 CV deaths, 164 CA deaths, and 203 NCV-NCA deaths. CV mortality was predicted by clinical variables, METs (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.88-0.96; P <.001), and ESE variables. CA mortality was independently predicted by age and METs (HR, 0.93; 95%CI, 0.87-0.99; P<.02), while NCV-NCA mortality was predicted by clinical variables (age, diabetes, diuretics, nitrates) and METs (HR, 0.83; 95%CI, 0.78-0.88; P<.001). Neither ischemia nor ESE variables were associated with an increased risk of NCV death.

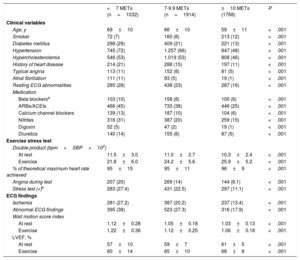

Baseline clinical and stress exercise ECG variables in 4717 women stratified by METs reached

| <7 METs (n=1032) | 7-9.9 METs (n=1914) | ≥10 METs (1768) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Age, y | 69±10 | 66±10 | 59±11 | <.001 |

| Smoker | 72 (7) | 160 (8) | 213 (12) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 298 (29) | 409 (21) | 221 (13) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 745 (72) | 1.257 (66) | 847 (48) | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 546 (53) | 1.019 (53) | 808 (46) | <.001 |

| History of heart disease | 214 (21) | 288 (15) | 197 (11) | <.001 |

| Typical angina | 113 (11) | 152 (8) | 81 (5) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 111 (11) | 93 (5) | 19 (1) | <.001 |

| Resting ECG abnormalities | 285 (28) | 438 (23) | 287 (16) | <.001 |

| Medication | ||||

| Beta blockersa | 103 (10) | 158 (8) | 100 (6) | <.001 |

| ARBs/ACEIs | 466 (45) | 733 (38) | 446 (25) | <.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 139 (13) | 187 (10) | 104 (6) | <.001 |

| Nitrites | 316 (31) | 387 (20) | 259 (15) | <.001 |

| Digoxin | 52 (5) | 47 (2) | 19 (1) | <.001 |

| Diuretics | 140 (14) | 155 (8) | 87 (5) | <.001 |

| Exercise stress test | ||||

| Double product (bpm×SBP×103) | ||||

| At rest | 11.5±3.0 | 11.0±2.7 | 10.3±2.4 | <.001 |

| Exercise | 21.8±6.0 | 24.2±5.6 | 25.9±5.2 | <.001 |

| % of theoretical maximum heart rate achieved | 95±15 | 95±11 | 96±9 | <.001 |

| Angina during test | 207 (20) | 269 (14) | 144 (8.1) | <.001 |

| Stress test (+)b | 283 (27.4) | 431 (22.5) | 297 (11.1) | <.001 |

| ECG findings | ||||

| Ischemia | 281 (27.2) | 387 (20.2) | 237 (13.4) | <.001 |

| Abnormal ECG findings | 395 (38) | 523 (27.3) | 316 (17.9) | <.001 |

| Wall motion score index | ||||

| At rest | 1.12±0.28 | 1.05±0.18 | 1.03±0.13 | <.001 |

| Exercise | 1.22±0.36 | 1.12±0.25 | 1.06±0.18 | <.001 |

| LVEF, % | ||||

| At rest | 57±10 | 59±7 | 61±5 | <.001 |

| Exercise | 60±14 | 65±10 | 68±8 | <.001 |

ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ECG, echocardiogram; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; METs, metabolic equivalents; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation unless otherwise specified

CV and NCV-NCA deaths were 4 times more likely in women with good functional capacity compared with poor functional capacity (2.2% vs 0.6%; P<.001 for CV mortality and 1.4% vs 0.3%, P<.001 for NCV-NCV mortality). CA deaths, in turn, were twice as likely in women with poor functional capacity (0.9 vs 0.4%, P<.001).

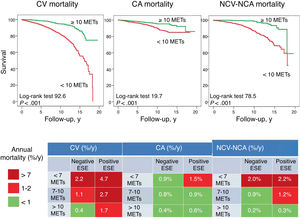

Annual NCV mortality was less than 0.7% in women who reached 10 METs irrespective of imaging findings. Annual CV mortality was also less below 0.7% in women with negative imaging findings and good functional capacity. The other subgroups had a higher risk of death (figure 1).

Survival curves for women with ≥10 or <10 METs showing annual mortality rates according to ECG images and functional capacity in an exercise stress ECG test. CA, cancer; CV, cardiovascular; ECG, echocardiogram; ESE, exercise stress electrogram; MET, metabolic equivalent; NCV-NCA, noncardiovascular-noncancer.

Our results confirm previous findings showing the beneficial effects of physical activity.1–4 Data on these benefits, however, are lacking for women, and not all studies have analyzed the effects on specific causes of death. One advantage of ESE over other techniques is that it not only captures images of cardiac function during normal exercise but also provides data that are independent of these images. In our series, the ECG images provided prognostic information on the risk of CV mortality, while the treadmill stress data offered information on the risk of CV, CA, and NCV-NCA mortality. Women with abnormal imaging findings were more likely to die of a CV cause, while those with poor functional capacity were more likely to die of any cause, irrespective of ECG images. This is important, as women with negative imaging findings could be reassured that their risk of death is low, but this, of course, is only true if they have good functional capacity.

The authors of a study of a pharmacological stress ECG found that patients with abnormal imaging findings also had an increased risk of CA mortality, attributable to subsequent exposure to procedures using radiation.5 Unlike us, however, they did not find that women with abnormal imaging findings had an increased risk of NCV mortality. While imaging findings were predictive of CV mortality in our study, the data from the treadmill stress test (METs) predicted not only CV mortality, but also CA and NCV-NCA mortality. Completion of stage IV of the Bruce treadmill protocol is equivalent to 10 METs, or to running at 10.4km/h or climbing 4 flights of stairs at a fast pace. Physical activity has positive effects on blood pressure and metabolism (and hence on the CV system) and it also reduces inflammation and improves immune response. Our findings add to the understanding that good physical fitness can help increase life expectancy in women.

We have shown that an ESE can predict CA and NCV-NCA mortality in addition to CV mortality. Physically fit women, ie, women who reach 10 METs in an ESE, have a lower risk of mortality, whatever the cause.

FundingPartially financed by CIBER funds.

.