Several trials have tested the diagnostic and prognostic value of stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in ischemic heart disease. However, scientific evidence is lacking in the older population, and the available techniques have limitations in this population. The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of stress CMR in the elderly.

MethodsWe prospectively studied consecutive patients referred for stress CMR to rule out myocardial ischemia. The cutoff age for the elderly population was 70 years. Stress CMR study was performed according to standardized international protocols. Hypoperfusion severity was classified according to the number of affected segments: mild (1-2 segments), moderate (3-4 segments), or severe (> 4 segments). We analyzed the occurrence of major events during follow-up (death, acute coronary syndrome, or revascularization). Survival was studied with the Kaplan-Meier method and multivariate Cox regression models.

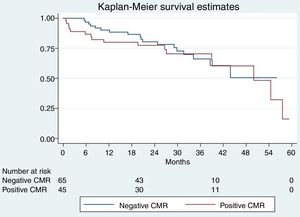

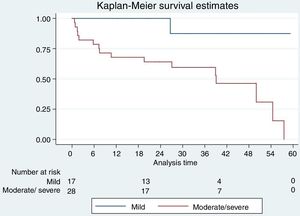

ResultsOf an initial cohort of 333 patients, 110 were older than 70 years. In 40.9% patients, stress CMR was positive for ischemia. The median follow-up was 26 [18-37] months. In elderly patients there were 35 events (15 deaths, 10 acute coronary syndromes, and 10 revascularizations). Patients with moderate or severe ischemia were at a higher risk of events, adjusted for age, sex, and cardiovascular risk (HR, 3.53 [95%CI, 1.41-8.79]; P=.01).

ConclusionsModerate to severe perfusion defects in stress CMR strongly predict cardiovascular events in people older than 70 years, without relevant adverse effects.

Keywords

The incidence and mortality of ischemic heart disease (IHD) increases with age.1,2 One of the reasons for the increased mortality is that diagnosis in the elderly is more complex because of the atypical presentation of IHD in this patient population (eg, fatigue, dizziness, atypical chest pain).3,4 Moreover, specifically validated cardiovascular risk scales are lacking and, in many cases, the available techniques are more difficult to perform and interpret in the elderly.5,6 However, correct diagnosis allows the implementation of adequate treatment, including coronary revascularization, which may improve prognosis.7–9

Current indications for a correct diagnostic testing of IHD have been established by clinical practice guidelines. These are based on the pretest probability of the patient developing the disease, which is calculated according to several parameters such as sex, resting electrocardiogram, chest pain characteristics, and exercise capacity.10,11 Some of these parameters have substantial limitations in elderly patients. Thus, the usefulness and safety of each of the available techniques must be evaluated individually.

Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) has proven to be useful for the diagnosis of myocardial ischemia.12,13 Furthermore, this technique allows reclassification of IHD pretest probability and also predicts cardiovascular events.14,15 However, the mean age of the individuals included in large study series is around 55 to 60 years, and populations older than 70 years are mostly underrepresented.16

The aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of stress CMR to predict cardiovascular events in patients older than 70 years. In addition, the safety of this diagnostic test in the elderly and the capability of stress CMR to reclassify their pretest probability in the absence of validated risk scales was also evaluated.

METHODSPatient populationWe prospectively studied all individuals who underwent stress CMR in our unit between 2009 and 2013. The decision to refer patients for this specific test over others was based on the clinical criteria of the referring cardiologist and following current clinical practice guidelines.17 We excluded patients with classic contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging, such as claustrophobia, pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, magnetic resonance imaging-unsafe objects, and chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Individuals were instructed to avoid caffeine-containing food and drinks 24hours prior to the CMR examination. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee (reference 096/2010) and all patients signed an informed consent form.

Clinical data such as cardiovascular risk factors, including body mass index, smoking history, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, family history of IHD and previous cardiovascular disease; clinical parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure and baseline heart rate, and analytical measures, including low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, baseline glucose levels, glycosylated hemoglobin and estimated glomerular filtration rate, were recorded in the outpatient cardiology clinic. The HeartScore for a low-risk population (Spain) was used to estimate the cardiovascular risk of each patient. The diabetic population and those patients with known IHD were considered as being at very high risk. We calculated the risk in patients aged at least 70 years by extrapolating the HeartScore, as indicated by clinical practice guidelines.18

Stress cardiac magnetic resonance protocolThe stress CMR studies were carried out by a cardiologist and a radiologist on a 1.5 T magnet (MAGNETOM Symphony and MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany), according to the 2008 recommendations of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.19 A total dose of 0.2 mmol/kg of gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin-Wedding, Germany) was administered at 4 mL/s after maximum hyperemia induced by increasing doses of intravenous adenosine (140, 180, and 210 μg/kg/min) for 4-6minutes in order to achieve an appropriate response: an increase in heart rate of at least 10 bpm and/or decrease in systolic blood pressure by at least 10mmHg.20

The test was visually analyzed and classified as positive for ischemia if reversible perfusion defects were detected. The degree of hypoperfusion was classified as mild (1-2 affected segments), moderate (3-4 segments) or severe (more than 4 segments). As for the analysis, moderate and severe perfusion defects were jointly evaluated. In those segments with ischemic late gadolinium enhancement, ischemia was considered if there was a reversible perfusion defect greater than the scar extension.

Patient follow-upFollow-up was scheduled every 3 to 6 months in the outpatient clinic or by telephone according to the cardiologist's criteria and patient preference until the end of follow-up or the first occurrence of an event: death from any cause, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and/or need for revascularization. As our objective was to establish the diagnostic and prognostic values of stress CMR, we considered a combined reference pattern that included coronary angiography guided by the result of the test or the appearance of the cardiovascular events. The indication and timing of coronary angiography depended on the criteria of the cardiologist and patient preference.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range in nonparametric data, and qualitative variables as number and percentage. Continuous quantitative variables were compared using the Student t test or the sum of Wilcoxon ranges in nonparametric data. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. A significance level of .05 (bilateral) was established for all statistical tests.

The survival distribution related to time to an event was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, analyzing the existence and degree of ischemia (mild vs moderate/severe). To compare survival curves, the log-rank test was employed. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was conducted to calculate the adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and to determine the effect of several variables on survival function. Univariate analysis was performed to select variables for the multivariate analysis. Variables with a result of P <.01 in the univariate analysis were selected for the multivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, a P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, United States) and SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

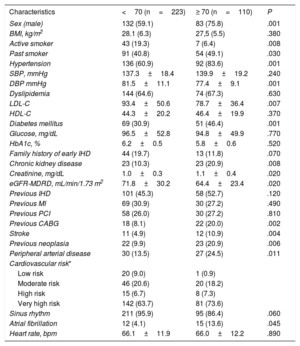

RESULTSPatientsOf the initial cohort of 333 patients undergoing stress CMR (76.3% men, mean age 64.6±10.6 years), 223 patients (66.7%) were identified as being younger than 70 years and 110 (33%) as being at least 70 years old. The baseline characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1. Patients aged 70 years or older were predominantly male and showed a higher prevalence of previous smoking history, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, previous neoplasia, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, and atrial fibrillation, thus resulting in a higher cardiovascular risk HeartScore. There were no statistically significant differences in the percentages of previous coronary disease, previous myocardial infarction, or in the other clinical parameters, although low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the percentage of active smokers were lower in the elderly population.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the patient cohort evaluated in this study

| Characteristics | <70 (n=223) | ≥ 70 (n=110) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 132 (59.1) | 83 (75.8) | .001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1 (6.3) | 27,5 (5.5) | .380 |

| Active smoker | 43 (19.3) | 7 (6.4) | .008 |

| Past smoker | 91 (40.8) | 54 (49.1) | .030 |

| Hypertension | 136 (60.9) | 92 (83.6) | .001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 137.3±18.4 | 139.9±19.2 | .240 |

| DBP mmHg | 81.5±11.1 | 77.4±9.1 | .001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 144 (64.6) | 74 (67.3) | .630 |

| LDL-C | 93.4±50.6 | 78.7±36.4 | .007 |

| HDL-C | 44.3±20.2 | 46.4±19.9 | .370 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 69 (30.9) | 51 (46.4) | .001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 96.5±52.8 | 94.8±49.9 | .770 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.2±0.5 | 5.8±0.6 | .520 |

| Family history of early IHD | 44 (19.7) | 13 (11.8) | .070 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 23 (10.3) | 23 (20.9) | .008 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 | .020 |

| eGFR-MDRD, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 71.8±30.2 | 64.4±23.4 | .020 |

| Previous IHD | 101 (45.3) | 58 (52.7) | .120 |

| Previous MI | 69 (30.9) | 30 (27.2) | .490 |

| Previous PCI | 58 (26.0) | 30 (27.2) | .810 |

| Previous CABG | 18 (8.1) | 22 (20.0) | .002 |

| Stroke | 11 (4.9) | 12 (10.9) | .004 |

| Previous neoplasia | 22 (9.9) | 23 (20.9) | .006 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 30 (13.5) | 27 (24.5) | .011 |

| Cardiovascular risk* | |||

| Low risk | 20 (9.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Moderate risk | 46 (20.6) | 20 (18.2) | |

| High risk | 15 (6.7) | 8 (7.3) | |

| Very high risk | 142 (63.7) | 81 (73.6) | |

| Sinus rhythm | 211 (95.9) | 95 (86.4) | .060 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12 (4.1) | 15 (13.6) | .045 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 66.1±11.9 | 66.0±12.2 | .890 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IHD, ishemic heart disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

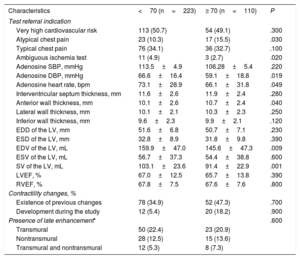

The most common CMR indications were suspicion of coronary artery disease in very high cardiovascular risk patients or with typical chest pain (Table 2). The adenosine dose was similar in both groups (163.2±28.8 μg/kg/min and 160.5±27.2 μg/kg/min for patients at aged least 70 years and younger than 70 years, respectively; P=.39). There were no major complications. A minor complication occurred in the group older than 70 years (transient atrioventricular block) and 3 minor complications were observed in individuals younger than 70 years (transient atrioventricular block in 2 and a chest pain episode not requiring nitroglycerine in 1).

Clinical indications for stress cardiac magnetic resonance and cardiac magnetic resonance results

| Characteristics | <70 (n=223) | ≥ 70 (n=110) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test referral indication | |||

| Very high cardiovascular risk | 113 (50.7) | 54 (49.1) | .300 |

| Atypical chest pain | 23 (10.3) | 17 (15.5) | .030 |

| Typical chest pain | 76 (34.1) | 36 (32.7) | .100 |

| Ambiguous ischemia test | 11 (4.9) | 3 (2.7) | .020 |

| Adenosine SBP, mmHg | 113.5±4.9 | 106.28±5.4 | .220 |

| Adenosine DBP, mmHg | 66.6±16.4 | 59.1±18.8 | .019 |

| Adenosine heart rate, bpm | 73.1±28.9 | 66.1±31.8 | .049 |

| Interventricular septum thickness, mm | 11.6±2.6 | 11.9±2.4 | .280 |

| Anterior wall thickness, mm | 10.1±2.6 | 10.7±2.4 | .040 |

| Lateral wall thickness, mm | 10.1±2.1 | 10.3±2.3 | .250 |

| Inferior wall thickness, mm | 9.6±2.3 | 9.9±2.1 | .120 |

| EDD of the LV, mm | 51.6±6.8 | 50.7±7.1 | .230 |

| ESD of the LV, mm | 32.8±8.9 | 31.8±9.8 | .390 |

| EDV of the LV, mL | 159.9±47.0 | 145.6±47.3 | .009 |

| ESV of the LV, mL | 56.7±37.3 | 54.4±38.8 | .600 |

| SV of the LV, mL | 103.1±23.6 | 91.4±22.9 | .001 |

| LVEF, % | 67.0±12.5 | 65.7±13.8 | .390 |

| RVEF, % | 67.8±7.5 | 67.6±7.6 | .800 |

| Contractility changes, % | |||

| Existence of previous changes | 78 (34.9) | 52 (47.3) | .700 |

| Development during the study | 12 (5.4) | 20 (18.2) | .900 |

| Presence of late enhancement* | .600 | ||

| Transmural | 50 (22.4) | 23 (20.9) | |

| Nontransmural | 28 (12.5) | 15 (13.6) | |

| Transmural and nontransmural | 12 (5.3) | 8 (7.3) | |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EDD, end diastolic diameter; EDV, end diastolic volume; ESD, end systolic diameter; ESV, end systolic volume; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SV, systolic volume.

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The stress CMR in patients younger than 70 years was negative for ischemia in 159 (71.3%) and positive in 64 (28.7%). The perfusion defect was mild in 28 individuals (43.7%) and moderate/severe in 36 patients (56.3%). In those at least 70 years, the result was negative in 65 (59.1%) and positive in 45 (40.9%), the perfusion defect being mild in 17 (37.8%) and moderate/severe in 28 (62.2%). There were no significant differences in the percentages of the presence of late gadolinium enhancement or in the development of contractility changes during the exam. A positive stress CMR result was more likely with age (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 1.02-1.07; P=.03).

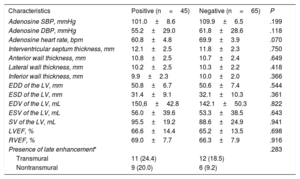

In patients older than 70 years, those with a positive result were more frequently men with previous MI and peripheral arterial disease. There were no statistically significant differences in the rest of the baseline characteristics (Table 3). Moreover, there were no differences in CMR parameters, even in the presence of late gadolinium enhancement, according to the result of the test (Table 4).

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients ≥ 70 years according to the result of cardiac magnetic resonance (positive/negative)

| Characteristics | Positive (n=45) | Negative (n=65) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 39 (86.7) | 43 (66.2) | .002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4±5.5 | 27.5±5.6 | .450 |

| Active smoker | 3 (6.7) | 4 (6.1) | .350 |

| Past smoker | 26 (55.5) | 28 (43.1) | .300 |

| Hypertension | 35 (77.7) | 57 (87.7) | .170 |

| SBP, mmHg | 141.7±18.2 | 138.6±19.9 | .797 |

| DBP, mmHg | 76.8±9.2 | 77.8±9.0 | .296 |

| Dyslipidemia | 33 (73.3) | 41 (63.1) | .260 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 80.4±34.4 | 77.5±38.0 | .660 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 45.8±15.7 | 46.8±22.4 | .398 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (42.2) | 32 (49.2) | .470 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 96.6±46.0 | 93.6±52.6 | .623 |

| Family history of early IHD | 6 (13.3) | 7 (10.8) | .070 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 (26.7) | 11 (16.9) | .200 |

| eGFR-MDRD, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 62.2±20.9 | 65.9±25.1 | .207 |

| Previous MI | 20 (44.4) | 10 (15.4) | .001 |

| Previous PCI | 17 (37.7) | 13 (20.0) | .040 |

| Previous CABG | 13 (28.9) | 9 (13.8) | .060 |

| Stroke | 2 (4.4) | 10 (15.4) | .120 |

| Previous neoplasia | 10 (22.2) | 13 (20.0) | .780 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 16 (35.6) | 11 (16.9) | .030 |

| Cardiovascular risk* | .100 | ||

| Low risk | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Moderate risk | 4 (8.9) | 16 (24.6) | |

| High risk | 3 (6.7) | 5 (7.7) | |

| Very high risk | 38 (84.4) | 43 (66,2) | |

| Sinus rhythm | 41 (91.1) | 54 (83.1) | .08 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (8.9) | 11 (16.9) | |

| Heart rate, bpm | 65.3±11.4 | 66.4±12.9 | .330 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Cardiac magnetic resonance results in patients ≥ 70 years according to the result of cardiac magnetic resonance (positive/negative)

| Characteristics | Positive (n=45) | Negative (n=65) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine SBP, mmHg | 101.0±8.6 | 109.9±6.5 | .199 |

| Adenosine DBP, mmHg | 55.2±29.0 | 61.8±28.6 | .118 |

| Adenosine heart rate, bpm | 60.8±4.8 | 69.9±3.9 | .070 |

| Interventricular septum thickness, mm | 12.1±2.5 | 11.8±2.3 | .750 |

| Anterior wall thickness, mm | 10.8±2.5 | 10.7±2.4 | .649 |

| Lateral wall thickness, mm | 10.2±2.5 | 10.3±2.2 | .418 |

| Inferior wall thickness, mm | 9.9±2.3 | 10.0±2.0 | .366 |

| EDD of the LV, mm | 50.8±6.7 | 50.6±7.4 | .544 |

| ESD of the LV, mm | 31.4±9.1 | 32.1±10.3 | .361 |

| EDV of the LV, mL | 150,6±42.8 | 142.1±50.3 | .822 |

| ESV of the LV, mL | 56.0±39.6 | 53.3±38.5 | .643 |

| SV of the LV, mL | 95.5±19.2 | 88.6±24.9 | .941 |

| LVEF, % | 66.6±14.4 | 65.2±13.5 | .698 |

| RVEF, % | 69.0±7.7 | 66.3±7.9 | .916 |

| Presence of late enhancement* | .283 | ||

| Transmural | 11 (24.4) | 12 (18.5) | |

| Nontransmural | 9 (20.0) | 6 (9.2) |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EDD, end diastolic diameter; EDV, end diastolic volume; ESD, end systolic diameter; ESV, end systolic volume; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SV, systolic volume.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Follow-up was available for all patients. After a median follow-up time of 26 [18-37] months 70 events were recorded, 35 events in each group. In patients at least 70 years, there were 15 deaths (4 in the positive CMR group), 10 ACS (8 in the positive CMR group), and 10 revascularizations (7 in the positive CMR group). In those younger than 70 years, 7 deaths, 12 ACS, and 16 revascularizations were recorded. Events were more likely to occur in elderly patients than in younger patients (odds ratio, 1.05; 95%CI, 1.02-1.08; P=.04).

In the survival analysis of patients older than 70 years, there were no significant differences according to the result of the stress CMR (positive vs negative, Kaplan-Meier survival curves, Log Rank test; P=.69). Significant differences were obtained depending on the degree of positivity (hypoperfusion) of the stress CMR (mild positive vs moderate/severe positive; Kaplan-Meier survival curves; log rank test; P=.003) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In patients with a positive stress CMR test, those with a moderate or severe degree of ischemia had a higher risk of having an event adjusted for age (older or younger than 70 years), sex and cardiovascular risk (HR, 3.53; 95% CI 1.41-8.79; P=.01). Therefore, a positive stress CMR with a moderate or severe hypoperfusion defect predicted the appearance of cardiovascular events in the follow-up in patients older than 70 years.

Finally, in patients with a positive result in the stress CMR, the degree of ischemia was confirmed as an independent predictor of events (HR 2.81; 95%CI 1.11-7.11; P=.03), independently of previous MI, late gadolinium enhancement, age, cardiovascular risk, and sex.

DISCUSSIONThe main finding of our study is that elderly patients with a moderate or severe degree of ischemia on stress CMR have a higher risk of having an event during follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the prognostic value of stress CMR in elderly patients in routine clinical practice.

In our study cohort, elderly patients had a high prevalence of both classic (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus) and nonclassic (chronic kidney disease or previous neoplasia) cardiovascular risk factors. However, the calculation of cardiovascular risk as indicated by the clinical practice guidelines21 may not be accurate in the elderly. For example, in our cohort, 73.6% of the patients would have been classified as being at very high cardiovascular risk, and accordingly, they may require invasive testing. In the elderly, however, this approach has a high rate of complications and adverse effects.9,22,23 In this scenario, routine use of noninvasive tests would allow reclassification and selection of patients who can benefit most from treatments that improve quality of life and prognosis.9

Suspicion of IHD in the elderly is also complicated by the presence of atypical symptoms and the clinical characteristics of this patient population (eg, frailty, inability to perform exercise, baseline electrocardiographic alterations), which can interfere in the calculation of the pretest probability of the disease and may affect the indication for different diagnostic tests. As an example, in the CLARIFY trial, most the elderly patients with coronary disease were asymptomatic, partly due to reduced physical activity.3 In our sample, the clinical indication for stress CMR was atypical chest pain in 15.5% of the elderly patients, whereas the percentage of requests for this clinical reason was slightly higher in individuals younger than 70 years (10.3% vs 15.5%).

There are few studies on the use of noninvasive diagnostic tests in the elderly population, and in clinical practice it is assumed that their accuracy is similar to that in the general population. Jeger et al.5 observed the usefulness of exercise stress and pharmacological stress echocardiography in patients over 75 years and Gurunathan et al.24 underlined the prognostic value of stress echocardiography in octogenarians. In the case of CMR, Barbier et al.25 demonstrated that the detection of a previous infarction predicts the appearance of events in people older than 70 years.

However, some studies have demonstrated that the degree of ischemia is one of the most relevant parameters in prognostic terms. Rösner et al.26 recently demonstrated that, in a previously revascularized population, the presence of 3 positive ischemic segments in a stress test was necessary to guide decision-making. In another study, Vincenti et al.,27 concluded that the presence of ≥ 1.5 ischemic segments in stress CMR studies was the most powerful predictor of events. Thus, in our study in patients older than 70 years, the presence of inducible ischemia, involving 3 or more segments increased the probability of having a cardiovascular event 3.5-fold, regardless of cardiovascular risk stratification and sex. These reasons can explain the nonsignificant result in survival when considering the global results of the stress CMR test and the significant differences when the degree of ischemia (mild vs moderate/severe) is considered. In addition, the importance of the degree of ischemia is independent of other parameters, such as the presence late gadolinium enhancement.

As in other CMR studies performed in the general population, our findings may help reclassifying the pretest probability of elderly patients.28 Thus, the use of stress CMR may reduce the number of unnecessary invasive tests and may be useful to guide a potential revascularization in the ischemic territories in this specific population. Thus, in our study stress CMR identified patients requiring invasive coronary angiography, since most of revascularizations and ACS appeared in patients with a positive stress CMR. The differences in mortality can be explained because people older than 70 years with a negative CMR can die from other age-related reasons apart from cardiovascular events.

Furthermore, stress CMR has been shown to be safe. Similarly to large scale registries, such as the EuroCMR,29 no relevant adverse effects were recorded, which supports the safety of CMR in the elderly. This observation places stress CMR as an accurate test in the study of IHD in this patient population. Moreover, our study has also demonstrated in individuals older than 70 years that a stress CMR protocol that includes perfusion with adenosine and viability testing after gadolinium injection is the most powerful tool to predict events.30

This study has some limitations. First, the cutoff age defining the geriatric population varies widely, especially when frailty criteria are not taken into account. In this study, the cutoff age for determining the geriatric population was established at ≥ 70 years, although it has been classically defined at 65 years.31 Second, in this study the endpoint was all-cause death and not cardiovascular death, since the cause of death could not be accurately identified in all cases. Third, this is a real-word clinical practice study and not a double-blind, randomized trial, thus invasive coronary angiography performance guided by the CMR result was more frequent in patients with moderate or severe ischemia. Finally, the percentage of women was low, although similar to that in other studies.

CONCLUSIONSAccording to our results, the presence of a moderate to severe perfusion defect in stress CMR strongly predicts the occurrence of cardiovascular events in patients older than 70 years. Thus, moderate to severe ischemia allows us to detect a population at very high cardiovascular risk. In addition, stress CMR is a safe test that allows risk stratification, which has implications for the clinical management of this specific population.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- -

Stress CMR is an established technique for the detection of myocardial ischemia, with an important role in prognosis and prediction of cardiovascular events. Among its advantages are: a) its safety, with no need for ionizing radiation, and b) ischemia and viability can be evaluated in the same examination. However, there is little experience in specific populations such as elderly patients.

- -

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the prognostic role of stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance with adenosine in elderly patients, a specific population in which it is sometimes difficult to rule out ischemia and establish prognosis.

- -

This is one of the few published works that takes into account the amount of ischemia detected in the cardiovascular magnetic resonance, and not only its presence.