Heart transplantation (HT) is the treatment of choice in cases of severe heart disease that do not respond to medical or surgical treatment. However, HT is also an invasive intervention and can have major psychiatric repercussions in recipients. Research on HT over the past decades has emphasized the importance of establishing an appropriate patient selection procedure to identify psychosocial factors that could influence patients’ clinical course before and after transplantation.1 To date, there is no systematic Spanish national registry of psychiatric factors associated with HT.2

The goal of this prospective observational study was to describe the principal psychiatric variables in patients on the transplant waiting list, and compare them with the results of a psychiatric follow-up examination 12 months after HT. The study examined patients consecutively included on the HT program at Hospital Clínic in Barcelona between January 2006 and December 2012 and who underwent HT. Participants were selected using a nonprobabilistic (incidental) sampling method and gave written informed consent. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Committee.

Sample size was calculated on the basis of an accepted risk α=0.05 and an accepted risk β<0.2 in a unilateral contrast, showing that a minimum of 9 patients was required to detect a difference of ≥ 5 points on the psychiatric scale used. The study protocol assumed a standard deviation of 5.3 and a loss of 20% during follow-up.

The pretransplant evaluation collected clinical and psychiatric variables using validated Spanish versions of the following instruments: a) structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders according to the classification of the American Psychiatric Association3 and b) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),4 a 14-item self-screening test. The HADS gives a total score between 0 and 42 points (with a maximum 21 points on each subscale). The cutoff point established for caseness of a psychiatric disorder was an overall score of 12, and the cutoffs for a depressive or anxiety disorder were 8 points on the respective subscale. The HADS test was repeated in the follow-up evaluation 12 months after HT.

The initial sample included 78 patients on the HT program. Of these, 17 did not complete the follow-up protocol at 12 months after HT (9 were lost to follow-up, and 8 died in the postoperative period due to complications with the transplant).

The Table shows the clinical characteristics collected in the baseline evaluation before HT. The cardiological profile of the study population was similar to that observed in national HT programs. In the baseline evaluation, 41% of patients had a total HADS score above the cutoff for psychiatric illness. This proportion dropped to 21% in the follow-up evaluation.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population (n=78)

| Age, y | 55.8±9.1 (30-72) |

| Men, % | 77 |

| Age at onset of heart disease, y | 44.9±11.2 (9-64) |

| Duration of disease before HT, y | 11.4±8.4 (0-42) |

| Pre-transplant heart disease etiology | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 33 (42) |

| Non-ischemic heart disease | 24 (31) |

| Valvular | 7 (9) |

| Congenital | 2 (2,6) |

| Other causes | 12 (15) |

| History of psychiatric illness | |

| No | 47 (60) |

| Yes | 31 (40) |

| Depressive disorder | 9 (12) |

| Substance abuse disorder | 8 (10) |

| Anxiety disorder | 7 (9) |

| Sleep disorder | 4 (5) |

| Adaptive disorder | 3 (4) |

| Current psychiatric illness | |

| No | 53 (68) |

| Yes | 25 (32) |

| Depressive disorder | 8 (10) |

| Sleep disorder | 8 (10) |

| Anxiety disorder | 7 (9) |

| Personality disorder* | 2 (3) |

| Current psychopharmacological treatment | |

| No treatment | 53 (68) |

| Receiving treatment | 25 (32) |

| Benzodiazepines | 11 (14) |

| SSRI | 6 (8) |

| SSRI and benzodiazepines | 4 (5) |

| SNRI | 2 (3) |

| Other antidepressive drugs | 2 (3) |

HT, heart transplantation; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

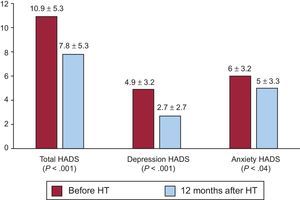

The mean HADS scores obtained in the evaluations are presented in the Figure. To compare means of repeated measures, we first performed a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess normality and goodness of fit. Means of variables that followed a normal distribution (total HADS score and the anxiety subscale) were compared by Student's t test. Variables on the HADS depression subscale followed a nonnormal distribution, and means were compared by Wilcoxon's nonparametric test. The statistical analysis showed significant reductions at 12-months’ follow-up in the total HADS score (P<.001) and in the scores for the subscales for depression (P<.001) and anxiety (P=.04).

In agreement with results published by other groups,5,6 our sample revealed a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the waiting-list period (32%), mostly depression and anxiety. Although the mean scores obtained in the HADS were below the cutoff for indicating morbidity, symptoms of anxiety and depression were significantly reduced 12 months after HT.

The main limitation of this study is that it cannot determine the influence of psychiatric variables on clinical course after HT, because it was not designed for a predictive analysis. Studies with larger patient populations would be needed to extend these results in order to more precisely determine the magnitude of the psychopathological changes produced after HT.

Psychiatric evaluation is important throughout the HT process because it enables the early detection and treatment of patients at risk of psychiatric disturbances. Our data support the conclusion that physical recovery after HT is generally accompanied by an improvement in psychological parameters at 12-months’ follow-up.