Cardiology practice requires complex organization that impacts overall outcomes and may differ substantially among hospitals and communities. The aim of this consensus document is to define quality markers in cardiology, including markers to measure the quality of results (outcomes metrics) and quality measures related to better results in clinical practice (performance metrics). The document is mainly intended for the Spanish health care system and may serve as a basis for similar documents in other countries.

Keywords

The physician-patient relationship remains the core of medical practice. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines has been shown to improve prognosis1–11; nevertheless, only a fraction of the recommendations are supported by undisputed evidence.12–16 Moreover, the complexity of the individual patient and the organization of medical practice have led to substantial individual, institutional, and intercountry variability.9,17–41 Significant efforts have been made to evaluate quality of care, particularly in cardiology, including the definition and identification of metrics in selected populations,42–62 public reporting,62–75 and the development of systems that enhance adherence to recommendations (eg, accreditations, payment of performance reports,75–83 and quality measures aimed at improving outcomes, including benchmarking.84–98

Overall, the process of quality measurement, benchmarking, quality report enhancement, and auditing is more advanced in the US than in Europe. However, in some European countries, this process is highly developed and is often centralized.92,99–105 One outstanding example is the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgery of Great Britain and Ireland.99 In Spain, the National Health Ministry and some of the autonomous communities have developed diverse reports on numerous standardized quality metrics for cardiology.57–62

Need for Quality StandardsQuality is often based on perception. Official and private organizations have voluntarily developed quality standards and benchmarking programs, using opinions or registries that seldom provide reliable information to measure quality. Moreover, attempts to assess the quality and safety of clinical practice have proliferated in recent years, leading to different rating systems that may yield completely different results and ratings for the same hospital during the same time period, thus adding confusion rather than helping to prove their usefulness and leading to doubts about whether quality can actually be measured by existing measures.82–85,89,106–109 However, quality could be either measured throughout the process of organization and delivery of care, or more importantly by the final results of clinical practice: clinical outcomes. Most importantly, benchmarking itself may be associated with a progressive improvement in performance and outcomes,60,89,92,99,110–112 highlighting the importance of standardization of quality measures and the responsibility of scientific societies.

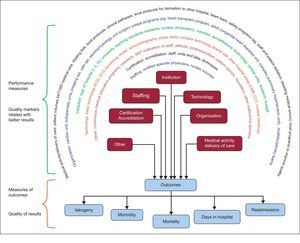

SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENTObjectivesThe objective of this document is to identify and standardize quality metrics in hospital cardiology practice. Two groups where clearly differentiated (Figure 1): a) selection of the best and most simplified metrics of the final quality of cardiology practice or outcomes measures (eg, a primary endpoint in a clinical trial), and b) identification of the performance metrics of clinical practice (performance measures) that are known to positively influence desirable outcomes (eg, surrogates in clinical trials).

Quality marker clusters related to better results in clinical practice (performance measures) and quality of results in clinical practice (outcome measure clusters). The latter are the best way to compare the quality of care in different hospitals/healthcare organizations and to provide information to the public. CCT, cardiac computed tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Beyond that, scientific societies and, in particular, health care authorities should be responsible for the implementation of programs to measure quality, ensure the quality of the data, benchmarking, and certification/accreditation of cardiology services.

This document focuses on quality measures of in-patient cardiovascular care. The quality of outpatient cardiovascular care will be considered in other documents.

Implementation and Further DevelopmentThis document will be limited to the identification and recommendation of the use of quality metrics. Beyond that, scientific societies and health care authorities should not only be responsible for the implementation of the program that best measures quality but should also ensure the reliability of data through audits and provide reports to the public. Three steps are recommended:

- 1.

Organization of databases including the necessary information for quality measuremets. Universal participation of hospitals is strongly recommended and the quality of the data must be ascertained through appropriate monitoring and audits for progressive improvement of data quality. If the data used to measure quality are not fully reliable, performance measures will be equivocal and will cause more harm and confusion than benefit. At this time in Spain, a mandatory national health care system database includes core information from all hospital discharge reports101 obtained from the ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) codes,113 but the quality of the data may be questioned as there is no quality control. Therefore, the SEC (Sociedad Española de Cardiología) is measuring outcomes through the minimum basic data set of the Ministry of Health registry within the RECALCAR (REsultados de CALidad en CARdiología)40 program, in an attempt to test quality and identify opportunities for improvement. Other institutions, including Health Departments of the autonomous communities, are using the same database for the same purpose, but are employing different parameters. Other countries have similar systems or obtain the information from mandatory or voluntary dedicated databases.83–85,99 This document intends to provide uniformity by standardizing quality markers.

- 2.

Benchmarking of hospital outcomes and assurance of public, controlled access to data and reports (the latter are a responsibility and decision of the health care authorities).

- 3.

Initiation of certification/accreditation of hospitals according to their results (responsibility of health care authorities).

The SEC, in cooperation with the SECTCV (Sociedad Española de Cirugía Torácica-Cardiovascular), founded a task force dedicated to identifying and defining quality markers in cardiology. Experts were identified and were invited to cover 8 areas of expertise: clinical cardiology, cardiac imaging, acute cardiac care, interventional cardiology, electrophysiology and arrhythmias, heart failure (HF), cardiac rehabilitation, and cardiac surgery. All European Society of Cardiology (ESC)103 and ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association)104 guidelines were reviewed, and recommendations related to quality standards were included in the document. Beyond the guidelines, an informal review was performed of the literature for quality metrics, performance metrics, and quality programs.

Main Components Considered for Quality Metrics RecommendationsThe following issues related to quality metrics and evaluation were identified and defined:

- •

Class of recommendations and levels of evidence.

- •

Types of hospitals.

- •

Clusters to assess quality in clinical practice.

- •

Main markers to assess quality of results in clinical practice (outcomes measures).

- •

Performance measures associated with better results in clinical practice (performance measures).

Cost and cost-effectiveness have become important components of quality performance54 but were not considered in this document.

Document Preparation, Review and Approval MethodThe task force was constituted by the SEC and the SECTCV. The document was sent to different cardiology societies, related scientific societies and health care authorities for comment and feedback. The final document was sent to external reviewers before simultaneous publication in Revista Española de Cardiología and Revista Española de Cirugía Cardiovascular. A shorter version will be published in the European Heart Journal.

Funding and Relationship With IndustryThe costs of convening the task force, arranging meetings, and secretarial assistance were covered by the SEC. All members of the task force volunteered their time and services and received no fees or payment in exchange for their service. No funding from industry was received by the members of the task force or the scientific societies involved in the preparation of this document. Members of the task force reported any possible conflicts of interest.

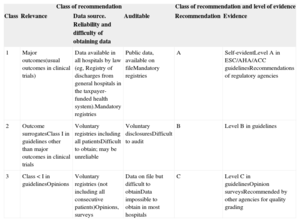

COMPONENTS TO DEFINE QUALITY METRICSGrading of Quality Markers. Class of Recommendation and Levels of EvidenceTo grade potential quality markers, the following aspects were considered: a) clinical and practical relevance; b) source and difficulty of obtaining the information; c) difficulty of auditing and ascertaining the information, and d) evidence in the literature. Three levels were established both for class of recommendation and level of evidence, as detailed in Table 1. The classification is based on recommendations in guidelines, the level of evidence attributed in published guidelines, recommendations from regulatory agencies or opinion surveys, and other sources. Mortality and stroke were considered as self-evident.101–104 To avoid confusion with the nomenclature of general clinical practice guidelines, the class of recommendation is graded as grades 1, 2 and 3 instead of I, II, and III.

Grading of Markers/Metrics./Metrics. Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence

| Class of recommendation | Class of recommendation and level of evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Relevance | Data source. Reliability and difficulty of obtaining data | Auditable | Recommendation | Evidence |

| 1 | Major outcomes(usual outcomes in clinical trials) | Data available in all hospitals by law (eg, Registry of discharges from general hospitals in the taxpayer-funded health system).Mandatory registries | Public data, available on fileMandatory registries | A | Self-evidentLevel A in ESC/AHA/ACC guidelinesRecommendations of regulatory agencies |

| 2 | Outcome surrogatesClass I in guidelines other than major outcomes in clinical trials | Voluntary registries including all patientsDifficult to obtain; may be unreliable | Voluntary disclosuresDifficult to audit | B | Level B in guidelines |

| 3 | Class < I in guidelinesOpinions | Voluntary registries (not including all consecutive patients)Opinions, surveys | Data on file but difficult to obtainData impossible to obtain in most hospitals | C | Level C in guidelinesOpinion surveysRecommended by other agencies for quality grading |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Hospitals differ in size, organization, volume, and technology. The complexity of cardiology requires the centralization of some technologies and services in selected hospitals for efficiency. High risk and highly complex patients may be transferred to “referral hospitals”, which poses a challenge to the comparison of performance and outcomes without establishing a hierarchy of hospitals with similar resources and patients.40 Most countries within the European Union have reorganized the practice of cardiology by concentrating certain procedures, such as surgery, complex percutaneous interventions, and complex arrhythmia ablations, in fewer hospitals. For quality benchmarking, the task force established 3 types of hospitals defined as low-, intermediate- and high-complexity according to their organization, resources, and the need to transfer patients to other hospitals (Table 2). This classification is arbitrary, may not apply to all countries, and may need refinement in the future. In addition, due to the growing complexity of cardiology practice, routine admission of patients in type I hospitals may not be recommended, except for palliative care or nursing home functions.

Type of Hospital

| Hospital | I (low complexity) | II (intermediate complexity) | III (high complexity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive cardiac care unit | No | Yes, but does not perform common complex techniques for ICC including hypothermia, cardiac circulatory support | Dedicated ICCUIncludes hypothermia, cardiac circulatory support and other complex ICC techniques |

| Interventional cardiology unit | No | Yes, but complex cases are transferred to other hospitalsPCI not available 24/7 | Yes, including complex casesPCI available 24 hours/7 days |

| Interventional electrophysiology | No, except pacemakers | Yes, but complex cases are transferred to other hospitals | Yes, including ICD/CRT implantation, and treatment of complex arrhythmias |

| Cardiac surgery | No | No | Yes, available 24 hours/7 days |

| Patient transfer | All cases for interventional cardiology including PCI procedures, electrophysiology and ablation of arrhythmias and cardiac surgery | Transfer of complex cases to another hospital including complex PCI, and structural percutaneous interventions, or ablation of arrhythmias or surgery | Only transfers patients that require a special unit, generally considered for national referral (eg, heart transplant, adult congenital heart disease, complex pulmonary hypertension unit)Receives complex patients from other hospitals |

CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICC, intensive cardiac care; ICCU, intensive cardiac care unit; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Assessing out-of-hospital practice and long-term follow-up presents special difficulties and is not considered in this document.

Clusters to Assess Overall Quality in Clinical PracticeQuality of care parameters may be grouped in clusters (Table 3), including institution characteristics, available technologies, staffing of the hospital and cardiac unit, organization, certification and accreditation, reputation, and patient opinion.49,58,73 All these clusters may influence outcomes, most are clearly identified in guidelines for clinical practice, and all should be taken into consideration in all hospitals. Some indicate the minimum requirements for accreditation of specific cardiology units such as electrophysiology, interventional cardiology laboratories, and cardiac surgery. Others reflect performance in clinical practice and others are directly related to the measurement of outcomes. Benchmarking of some of these parameters may be difficult, and obtaining the appropriate information may require a dedicated database that is difficult to standardize or complete and is even more difficult to accurately audit. Nevertheless, health care authorities should consider specific requirements for special units and may use some of them for benchmarking but, most importantly, for accreditation. Individual hospitals may monitor selected parameters as measures to identify suboptimal performance and opportunities for improvement.

Quality of Care Clusters

| Clinical performance measures | Cluster | Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Quality markers related to better results in clinical practice | Institution | Type of hospital (I, II, III)UniversityTeaching (students, residents, nurses, physicians, patient education)VolumesAccreditationsTechnologyCentral unitsResearchBudget |

| Technology | Basic technology (ECG, ECG monitoring, Holter, echocardiography, stress tests)Complex technology may be shared with other hospital areas (CMR, CCT, nuclear medicine) | |

| Staffing | Certified specialists, physicians, nursesVolumes | |

| Organization | Cardiac unitSubspecialty units (imaging lab, cath lab, electrophysiology unitSurgerySingle programs (eg, heart transplant program, adult congenital heart diseases unit, complex pulmonary hypertension unit)Multidisciplinary teams | |

| Certifications/accreditations | StaffUnits and labsTechniques | |

| Medical activityDelivery of Care | Patient volumes24/7/365 medical (cardiology) careWaiting listsLocal protocols, clinical pathways, standard of care proceduresLocal protocols for referral to other hospitalsHeart teamSafety programs (eg, staff and patient radiation, bleeding, medical errors)Local programs to improve quality | |

| Other | Continuous medical education programsResearch360° evaluation of staff, skills, attitude, professionalismPatient opinionReputation. Other institutions’ opinions | |

| Markers to measure quality of results in clinical practice | Outcomes | MortalityMorbidityNumber of days in hospitalReadmissionsIatrogeny |

CCT, cardiac computed tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Of special interest is the organization of safety programs (eg, staff and patient radiation, bleeding, infections, medical errors) and other local programs to improve quality.

Teamwork is always recommended and is mandatory between hospitals that transfer patients on a routine basis.

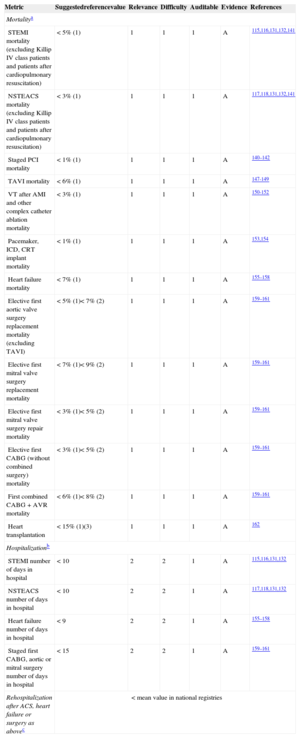

MAIN MARKERS TO MEASURE THE QUALITY OF RESULTS (OUTCOME MEASURES) IN CLINICAL PRACTICEClinical outcomes are the ultimate measure of quality of care in cardiology and there is no excuse to ignore them. Clinical outcomes are the result of the interactions of all quality measures related to quality of care; they should be clearly selected for benchmarking and should be made publicly available. The main outcomes in cardiology trials (mortality, hospitalization, myocardial infarction/reinfarction, and stroke) constitute the strongest reference for guideline recommendations (Table 4).48–52,99–102,104,105,114–121 They should be included in quality of care databases dedicated to explore the quality of care and should be accessible for audits. In addition, major safety parameters should be also considered for quality measurement and benchmarking.

Principal Markers Frequently Used to Assess Overall Quality of Results in Clinical Practice

| Metric | Relevance | Difficulty | Auditable | Evidence | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | Self-evident. Reliable only in well-organized, auditable registries/databases |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 1 | 2 | 2 | A | Difficult to ascertain. Needs adjudication. |

| Number of days in hospital | 1 | 2 | 2 | A | Reason for hospitalization dependent on health care systems and individual preferencesNumber of days in any hospital 30 days after index hospitalization |

| Stroke | 1 | 2 | 2 | A | Difficult to ascertain. Needs adjudicationNo reliable risk scores for corrections of results in different hospitals |

| Reinfarction | 1 | 2 | 2 | A | Difficult to ascertain. Needs adjudication |

| Safety (major bleeding, severe infections, medical errors, etc) | 1 | 2 | 2 | A | Difficult to ascertain. Needs adjudication and audits |

Mortality constitutes the first and most important metric recommended by this task force to measure the quality of results in clinical practice. The relevance of mortality is self-evident, it remains the most important outcome measure in clinical trials designed to change clinical practice, and is the most powerful evidence to support recommendations in practice guidelines. In many clinical settings, mortality is related to guideline adherence as well as performance measures,103,104,121,122 it is included in different programs that evaluate quality of care,6–9,40,99 and it can certainly be audited (class of recommendation 1, level of evidence A). Mortality may be classified as all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, or other cause-related mortality. All-cause mortality during the index hospitalization is the metric recommended by this task force, as different causes of mortality need adjudication for uniformity, which will not be possible except in dedicated registries. Ideally, mortality at a predefined follow-up (eg, 30 days after index hospitalization) is preferred instead of hospital mortality, but this may be difficult or impossible to ascertain except in well-organized dedicated registries. Mortality should be measured in uniform groups of patients and requires corrections for casemix complexity. Another caveat with mortality is that as a measure it requires a relatively large number of patients and may be statistically misleading or misinterpreted in low-complexity hospitals. In such cases, mortality may be measured through longer time periods and presented per year, but there is no excuse to avoid measuring mortality in cardiology patients.

Length of Hospital Stay and Readmission RatesThe length of hospital stay and readmission rates constitute the second metric recommended by this task force. Hospitalization reflects quality of care, impacts health care cost, is commonly used in quality programs,115–122 and is also included in many quality control databases. On the other hand, length of stay may not be as reliable as an outcome metric to compare the results of practice in different countries/areas where hospitalization may be driven not only by medical reasons but also by administrative and social determinants. In addition, rehospitalization may depend on other conditions or comorbidities, which are always difficult to properly determine. For this reason, hospitalization is recommended as a quality metric only when hospitals participate in a prospective, dedicated registry, where criteria for admission and discharge are predefined, or the cluster of hospitals is uniform. Ideally, hospitalization should be measured in a predetermined time period (eg, 30 days), but if reliable measurements are not possible, length of hospital stay is preferred and recommended. The task force also recommends measuring unplanned readmission for any cause to any acute care hospital within 30 days of hospital discharge (class of recommendation 2, level of evidence B).

Myocardial InfarctionIn-hospital or post-discharge myocardial infarction is one of the components of the main outcomes in clinical trials and registries in patients with ischemic heart disease. However, it may be a poor metric for outcomes due to the difficulties of standardizing the diagnosis in large populations, in particular during the first few days after hospital admission for acute coronary syndromes (ACS),115–123 and should only be used in dedicated, prospective, controlled registries (class of recommendation 2, level of evidence B).

StrokeDisabling stroke is self-relevant, is related to iatrogeny, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), surgery, and the use of antithrombotic therapy. Stroke is a metric included in registries and some quality programs.10,79,114 However, minor forms of stroke are difficult to diagnose without the routine use of imaging techniques, there are no reliable scales for stroke risk in different clinical settings, and this metric may represent a confounding factor for benchmarking if not centrally adjudicated.124–129 Stroke is a most important component for outcomes in clinical trials but inappropriate evaluation may lead to inaccurate representation of hospital performance and may potentially have serious unintended consequences; accordingly, stroke is only recommended as a quality measure when considering well organized, controlled, and audited registries (class of recommendation 2, level of evidence B).

SafetySafety parameters such as major bleeding, medical errors, infections, cardiac tamponade during percutaneous interventions, and other relevant clinical complications of clinical practice should be considered in quality performance reports. Again, the complexity of achieving uniform diagnosis and reporting in a large number of hospitals precludes the use of safety parameters for benchmarking of quality except when data are prospectively obtained in dedicated, controlled registries. Nevertheless, major bleeding, stroke, infections, medical errors, cardiac tamponade, and other safety parameters should be recorded locally to identify opportunities for improvement (class of recommendation 2, level of evidence B). Safety measures in quality programs will be addressed in detail in another publication.

ADJUSTMENT OF OUTCOMES METRICSThe probability of a patient dying is considered to be a combination of the patient's individual risk factors (case history) and the quality of the care provided (hospital-specific functionality).124–129 Overall mortality may be biased by the admission diagnosis, transfer of selected high-risk cases from other hospitals, or admission strategies. Some adjustments are needed to make outcome metrics reliable to compare clinical practice outcomes, selection of uniform populations, and risk adjustment.

Selection of Uniform PopulationsComparisons should be made only between similar hospitals and in selected, well-defined, high-risk specific populations with prognosis known to be dependent on overall cardiology treatment (diagnosis-related groups [DRGs]).40,58,130–138 Diagnosis-related groups relatively homogenize diagnosis and procedures, but are divided into too many groups, sometimes arbitrarily. Extreme high-risk and low-prevalence groups of patients that may only be admitted by some highly selected hospitals (such as patients with endocarditis, trauma, and those with complications of noncardiac surgery) should be excluded from analysis rather than corrected for risk.136,137 Sometimes this information is not well reflected in registries or databases, highlighting the importance of dedicated databases for the measurement of quality outcomes.137 Furthermore, diagnosis at admission may be imprecise (eg, endocarditis) or even worse, not included in the ICD-9-CM codes113 (eg, prehospital cardiac arrest admitted unconscious to the hospital). Exclusion of these DRGs could provide more uniform and reliable groups for benchmarking. Widespread introduction of the ICD-10 (Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases) codes will improve the classification of patients considering more contemporary diagnoses. Table 5 shows the recommended DRGs to assess overall quality of results in clinical practice and the recommended reference values.40,58,70,72,75,99,131–133,139–159

Grading of Quality Markers/Metrics. Recommended Measures to Assess Overall Quality of Results in Clinical Practice

| Metric | Suggestedreferencevalue | Relevance | Difficulty | Auditable | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortalitya | ||||||

| STEMI mortality (excluding Killip IV class patients and patients after cardiopulmonary resuscitation) | < 5% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 115,116,131,132,141 |

| NSTEACS mortality (excluding Killip IV class patients and patients after cardiopulmonary resuscitation) | < 3% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 117,118,131,132,141 |

| Staged PCI mortality | < 1% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 140–142 |

| TAVI mortality | < 6% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 147-149 |

| VT after AMI and other complex catheter ablation mortality | < 3% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 150-152 |

| Pacemaker, ICD, CRT implant mortality | < 1% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 153,154 |

| Heart failure mortality | < 7% (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 155–158 |

| Elective first aortic valve surgery replacement mortality (excluding TAVI) | < 5% (1)< 7% (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| Elective first mitral valve surgery replacement mortality | < 7% (1)< 9% (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| Elective first mitral valve surgery repair mortality | < 3% (1)< 5% (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| Elective first CABG (without combined surgery) mortality | < 3% (1)< 5% (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| First combined CABG + AVR mortality | < 6% (1)< 8% (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| Heart transplantation | < 15% (1)(3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 162 |

| Hospitalizationb | ||||||

| STEMI number of days in hospital | < 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | A | 115,116,131,132 |

| NSTEACS number of days in hospital | < 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | A | 117,118,131,132 |

| Heart failure number of days in hospital | < 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | A | 155–158 |

| Staged first CABG, aortic or mitral surgery number of days in hospital | < 15 | 2 | 2 | 1 | A | 159–161 |

| Rehospitalization after ACS, heart failure or surgery as abovec | < mean value in national registries | |||||

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NSTEACS, non—ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Reference values are meant as a guide. For benchmarking, a target reference value < median value in participating hospitals is strongly recommended.

30-day all-cause mortality is preferred over mortality before hospital discharge only if reliable data can be obtained (dedicated, auditable registries). 1: observed mortality (mean value). 2: expected mortality corrected for the logistic EuroSCORE for this population. 3: mortality or retransplantation.

Some corrections are needed for risk adjustment. Table 6 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the most common strategies for risk adjustment. At a minimum, corrections should be made for age and sex. The use of specific and validated risk scores will provide further refinement and make the metrics more reliable for benchmarking. Whenever possible, the use of simplified risk scores validated in clinical practice is strongly recommended.160–172 Nevertheless, some are too complex and difficult to assess in large populations, such as some important parameters (eg, biological markers) that may not be routinely used in every hospital and will not be available in every patient. This may be the case with HF.173–175 In such circumstances, it is recommended to use adjusted models, such as that published by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences of Ontario, Canada,176 which considers common risk factors usually present in clinical risk scales (age, sex, shock, diabetes mellitus with complications, congestive HF, malignant tumor, cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, and chronic renal failure). In addition to patient demographics and clinical variables, hierarchical models of risk adjustment (multilevel models)176–180 take into consideration specific effects at the “hospital” level. One problem is that the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences of Ontario adjustment model is not universally used, making it difficult to benchmark against other countries/systems. Furthermore, the reliability of this correction has not been fully validated in some specific clinical settings (ACS, stable coronary artery disease, bleeding, surgery, and other invasive procedures) and has not been universally accepted. Hence, whenever possible, more specific risk scores should be used that have been validated in clinical practice and recommended in guidelines. These include the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) or TIMI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) risk scores for ACS,163,165 EuroSCORE II risk score,166,167,172 and others.171,173–175

Risk Adjustment Corrections Commonly Used for Benchmarking of Outcomes

| Type of correction | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| None | Real figuresGood to compare overall results in very large populations, especially when no selection bias is expected (eg, benchmarking between countries or in the same country through different periods of time) | Different risk profiles impact the results, especially in not very large populations or biased populationsHospitals admitting the worst cases have the worst results |

| Age and sex | Classic when comparing overall results in large populations when no population selection bias is expectedGenerally accepted; used in many statistical reports of large populations | Incomplete refinement of population riskMay be unreliable in relatively small populations |

| Hospital clusters | Corrects for bias of patient admissions in different types of hospitals | Insufficient for risk correctionHospitals admitting the worst cases have the worst results |

| General risk correction | Some scores were validated (eg, ICES155) and used in quality benchmarking | Not compared and validated against disease-specific risk scoresNo universal risk score for all clinical settings with different risk factors for outcomes |

| Disease specific risk scores (eg: EuroSCORE II, GRACE, TIMI, SYNTAX, HAS-BLED, Stroke) | Validated for specific populationsRecommended in guidelines for risk stratification and therapeutic strategies in clinical practiceBest for specific registries; probably the best if universally accepted for risk correction in benchmarking | Not universally accepted/used for quality benchmarkingSome risk scores include data not available in large populations (eg, biomarkers in heart failure scores) |

| Risk standardized mortality ratios | Difficult to understand by nonprofessional observers | Not universally usedPredicted mortality may be inaccurately calculated |

| Risk score calculated in study populations used for benchmarking | Probably the best correction for benchmarking in a single study (eg, specific registry) | Impossible to apply universallyUnreliable when comparing very different populations (different registries, databases, countries) |

indicates the population selection and adjustments to compare outcomes among different hospitals. The recommended ICD-9-CM codes are listed in .

More complex adjustments allow the calculation of other indexes, such as the risk-standardized mortality ratio (the ratio of predicted mortality, which considers, on an individual basis, the functionality of the hospital treating the patient) to expected mortality (which considers a standard functionality according to the average of all the hospitals), multiplied by the crude mortality rate40,176; however, these metrics may be more difficult to understand by nonexpert observers (for whom the metrics and benchmarking are intended) and the lack of universal standardization makes benchmarking unreliable.

Universal standardization for risk correction should be a priority of scientific societies committed to improving the reliability of benchmarking in quality of care.

REPORTINGBenchmarking helps to identify problems and opportunities and to improve quality and outcomes.60,89,92,99,110–112

MediaQuality of care audits highlighting performance measures and outcomes are of interest to physicians and medical personnel, healthcare authorities, and the general public. Therefore, reporting of quality measures for outcomes should be transparent and available to all stakeholders. Use of the Internet for benchmark reporting is recommended but should be overseen by health care authorities or scientific societies.

Reporting FormatRates (eg, crude and risk adjusted) should be chosen over other forms of reporting (eg, odds ratios, predicted mortality) as they are better understood and preferred for benchmarking.178–184 The use of terms such as first, best, last, and worst, in benchmark reporting is discouraged. Averaged values or recommended target values should be included for reference. Table 7 summarizes different types of reporting results for benchmarking. Simple data are preferred for clarity.

Reporting for Benchmarking

| Type of report | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Selected populations:eg, STEMI excluding prehospital cardiac arrest unconscious at hospital arrivaleg, exclusion of low prevalence and very high risk populations (trauma, endocarditis, noncardiac surgery | More uniform populations for benchmarkingCorrects for confoundersMore uniform results without need for other corrections | Not real figures for the complete populationNo universal selection criteria acceptedBenchmarking between different registries etc unreliable due to difficulties in selecting appropriate populations |

| Crude observed values(number or percentage) | Represent the real problemEasy to understandGood for large populations | Unreliable for smaller populations because of lack of risk correction |

| Risk corrected figures | Corrects for risk population between clustersMore reliable | No universal risk correction accepted |

| Observed vs predicted (expected) ratios | Better describe performance for benchmarking | More difficult to understand than crude or percent values when reporting for nonprofessional readersNo universally validated algorithms to calculate expected valuesUsually, expected figures are higher than observed (eg, EuroSCORE) |

STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

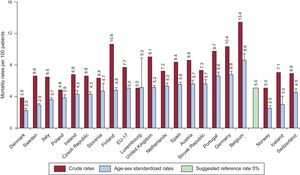

Graphic representation is preferred over tables for clarity. Graphs for clustering should include numbers in different hospitals or hospital clusters, as well as graphs for trends through different time periods. Median values and a possible reference value (eg, target value recommended in guidelines) should also be included as a reference target for outcomes for a particular measure. Figure 2 illustrates 30-day mortality rates in different European countries.32

Graphic reporting of metrics for benchmarking between different hospital clusters. Extracted with permission from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Different 30-day mortality rates after admission for acute myocardial infarction, 2009 (or nearest year).32 The suggested reference mortality rate is also indicated. EU, European Union. Reproduced from Health at a Glance: Europe 201232. Reference values from Steg et al.115

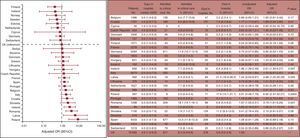

Tables may include detailed information but such information may be confusing or distract from the main objective of benchmarking. Tables should be complemented with figures that include main outcomes, preferably with actual values in percentage format, in addition to ratios and other information (Figure 3).183

Graphic reporting of differences in hospital mortality after surgical procedures (noncardiac) between European countries in the 7 days of the study. Adjusted odds ratios graph and table including detailed data. AVR, aortic valve replacement. Reproduced from the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland.183

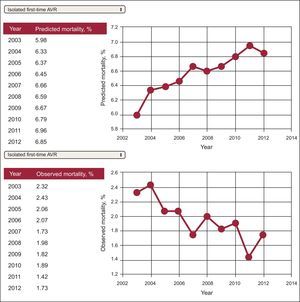

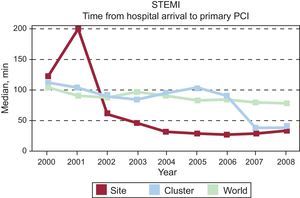

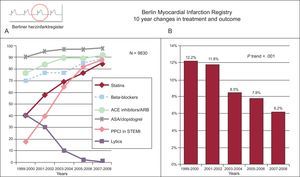

Trends in outcomes through different time periods are encouraged to illustrate the progress of a particular marker in a hospital or hospital cluster (self-benchmarking). This type of representation is illustrated in Figures 4182 and 5.138,179182.138,179 Combined reporting of metrics may illustrate a possible relationship between changes in treatment strategies and outcomes (Figure 6).184

Trends in outcomes for in-hospital mortality after first-time aortic valve replacement. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; AVR, aortic valve replacement; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; UK, United Kingdom. Reproduced with permission from Pearse et al.182

Benchmarking between different hospitals (single site and cluster of hospitals in a country (Spain) and complete cohort (world) showing temporal trends in door-to-balloon time in hospitals with primary percutaneous coronary intervention facilities. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Adapted from Spanish benchmark reports, Fox et al.138.

Combined reporting of metrics illustrating the change in the use of effective treatments in acute myocardial infarction and mortality. Berlin registry. A: medications and reperfusion therapy. B: hospital mortality for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non—ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Adapted from Röehnisch et al.184

Performance measures refer to measures of the quality of processes that are known to positively influence desirable outcomes. Common markers related to better results in clinical practice are grouped in 2 sections: a) resources directly related to patient care (hospital volume, desired technology, staffing, organization, patient services, accreditation), and b) the process of delivery of care for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and patient education (including local protocols, multidisciplinary teams, waiting lists, safety, and educational programs). These metrics are the gold standard for better health care organization and some (many) are related to better outcomes, but these are not appropriate to measure the quality of results and should not be considered as important as outcomes.

Eight different sections have been identified: Clinical cardiology and hospital-related markers, cardiac imaging, acute cardiac care, interventional cardiology, electrophysiology and complex arrhythmias, HF, cardiac rehabilitation, and cardiac surgery. Most of them are perceived as subspecialties in cardiology and require specific training, sometimes beyond the expertise of general cardiology. Some are already accredited by the ESC (cardiac imaging, electrophysiology and complex arrhythmias, acute coronary care, interventional cardiology and rehabilitation), but seldom by health care authorities. The American Board of Internal Medicine recognizes HF as a subspecialty. Cardiac surgery, obviously a different specialty, is also included in the document because of its intrinsic relationship with cardiology. Special units such as heart transplantation, adult congenital heart disease, or complex pulmonary hypertension units are accredited in Spain as national referral units,185 which through a dedicated process of selection, are audited every 2 years following a predefined protocol and are not included in this document. The task force recommends the referral of these patients to the same hospital to facilitate teamwork.

Only performance measures considered as class II recommendation with Level of evidence A were selected and included in this document. Class I recommendations were restricted to outcome measures.

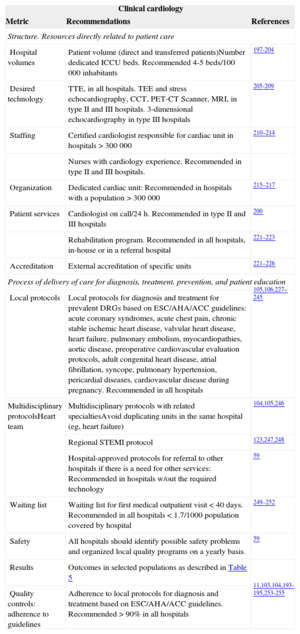

Clinical Cardiology and Hospital Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical PracticeSome quality markers are recommended for the accreditation of cardiology units of all hospitals (eg, staffing, technology, volumes); others are aimed at controlling internal quality or identifying problems and opportunities for improvement and are recommended for all hospitals.54,181,185–255 Arguably, the most relevant recommendations are the use of local protocols for diagnosis and treatment, based on ESC/AHA or country-specific guidelines and approved by the hospital.103,104,196 Teamwork with internal medicine and other related specialties, with special reference to primary care, should be a priority.186–195Table 8 shows selected metrics and provides a more detailed description of clinical cardiology and hospital-related markers.

General, Hospital-related and Clinical Cardiology Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Clinical cardiology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendations | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | Patient volume (direct and transferred patients)Number dedicated ICCU beds. Recommended 4-5 beds/100 000 inhabitants | 197-204 |

| Desired technology | TTE, in all hospitals. TEE and stress echocardiography, CCT, PET-CT Scanner, MRI, in type II and III hospitals. 3-dimensional echocardiography in type III hospitals | 205-209 |

| Staffing | Certified cardiologist responsible for cardiac unit in hospitals > 300 000 | 210–214 |

| Nurses with cardiology experience. Recommended in type II and III hospitals. | ||

| Organization | Dedicated cardiac unit: Recommended in hospitals with a population > 300 000 | 215–217 |

| Patient services | Cardiologist on call/24 h. Recommended in type II and III hospitals | 200 |

| Rehabilitation program. Recommended in all hospitals, in-house or in a referral hospital | 221–223 | |

| Accreditation | External accreditation of specific units | 221–226 |

| Process of delivery of care for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and patient education | ||

| Local protocols | Local protocols for diagnosis and treatment for prevalent DRGs based on ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines: acute coronary syndromes, acute chest pain, chronic stable ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, myocardiopathies, aortic disease, preoperative cardiovascular evaluation protocols, adult congenital heart disease, atrial fibrillation, syncope, pulmonary hypertension, pericardial diseases, cardiovascular disease during pregnancy. Recommended in all hospitals | 105,106,227–245 |

| Multidisciplinary protocolsHeart team | Multidisciplinary protocols with related specialtiesAvoid duplicating units in the same hospital (eg, heart failure) | 104,105,246 |

| Regional STEMI protocol | 123,247,248 | |

| Hospital-approved protocols for referral to other hospitals if there is a need for other services: Recommended in hospitals w/out the required technology | 59 | |

| Waiting list | Waiting list for first medical outpatient visit < 40 days. Recommended in all hospitals < 1.7/1000 population covered by hospital | 249–252 |

| Safety | All hospitals should identify possible safety problems and organized local quality programs on a yearly basis. | 59 |

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in Table 5 | |

| Quality controls: adherence to guidelines | Adherence to local protocols for diagnosis and treatment based on ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines. Recommended > 90% in all hospitals | 11,103,104,193-195,253-255 |

3D, 3-dimensional; ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; DRG, diagnosis-related groups; ICCU, intensive cardiac care unit; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET-CT, positron emission computed tomography; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

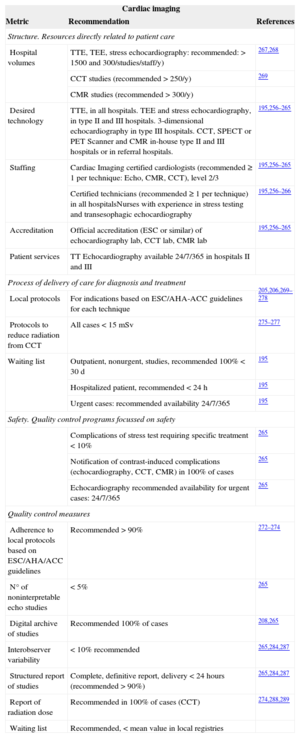

Cardiac imaging constitutes the core for diagnosis in cardiology and its rapid development in recent years, as well as its complexity, requires specific training and teamwork with other specialists. Technology should be available in all hospitals, in-house. or in referral hospitals. Transthoracic echocardiography performed by well-trained cardiologists is recommended in all patients and in all hospitals. For more complex techniques requiring specific training, accreditation, and certification is strongly recommended and teamwork may be useful with radiologists (nuclear imaging, cardiac computed tomography, cardiovascular magnetic resonance). Accreditation of imaging laboratories by the ESC or other official accreditation agencies is recommended, particularly in hospitals classified as type II and III. Quality controls include accreditation, low interobserver variability, and prompt systematic reports. Protocols aimed at reducing radiation doses in CT scans and the systematic reporting of the total radiation dose are recommended in every case256–292Table 9 shows selected metrics in cardiac imaging.

Cardiac Imaging Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Cardiac imaging | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | TTE, TEE, stress echocardiography: recommended: > 1500 and 300/studies/staff/y) | 267,268 |

| CCT studies (recommended > 250/y) | 269 | |

| CMR studies (recommended > 300/y) | ||

| Desired technology | TTE, in all hospitals. TEE and stress echocardiography, in type II and III hospitals. 3-dimensional echocardiography in type III hospitals. CCT, SPECT or PET Scanner and CMR in-house type II and III hospitals or in referral hospitals. | 195,256–265 |

| Staffing | Cardiac Imaging certified cardiologists (recommended ≥ 1 per technique: Echo, CMR, CCT), level 2/3 | 195,256–265 |

| Certified technicians (recommended ≥ 1 per technique) in all hospitalsNurses with experience in stress testing and transesophagic echocardiography | 195,256–266 | |

| Accreditation | Official accreditation (ESC or similar) of echocardiography lab, CCT lab, CMR lab | 195,256–265 |

| Patient services | TT Echocardiography available 24/7/365 in hospitals II and III | |

| Process of delivery of care for diagnosis and treatment | ||

| Local protocols | For indications based on ESC/AHA-ACC guidelines for each technique | 205,206,269–278 |

| Protocols to reduce radiation from CCT | All cases < 15 mSv | 275–277 |

| Waiting list | Outpatient, nonurgent, studies, recommended 100% < 30 d | 195 |

| Hospitalized patient, recommended < 24 h | 195 | |

| Urgent cases: recommended availability 24/7/365 | 195 | |

| Safety. Quality control programs focussed on safety | ||

| Complications of stress test requiring specific treatment < 10% | 265 | |

| Notification of contrast-induced complications (echocardiography, CCT, CMR) in 100% of cases | 265 | |

| Echocardiography recommended availability for urgent cases: 24/7/365 | 265 | |

| Quality control measures | ||

| Adherence to local protocols based on ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Recommended > 90% | 272–274 |

| N° of noninterpretable echo studies | < 5% | 265 |

| Digital archive of studies | Recommended 100% of cases | 208,265 |

| Interobserver variability | < 10% recommended | 265,284,287 |

| Structured report of studies | Complete, definitive report, delivery < 24 hours (recommended > 90%) | 265,284,287 |

| Report of radiation dose | Recommended in 100% of cases (CCT) | 274,288,289 |

| Waiting list | Recommended, < mean value in local registries | |

3D, three-dimensional; ACC, American College of Cardiology, AHA, American Heart Association; CCT, cardiac computed tomography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; Echo, echocardiography; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

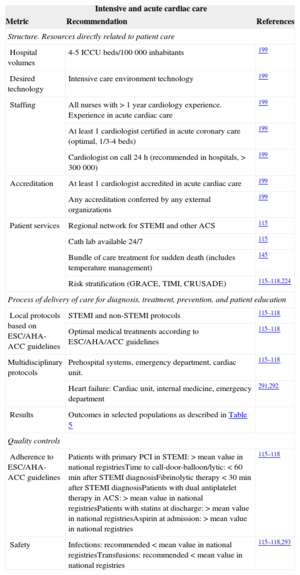

Acute cardiac care requires teamwork with out-of-hospital professionals, emergency departments, and internal medicine and intensive care physicians that follow well-defined protocols for common cardiac conditions such as acute myocardial infarction and ACS. Protocols that follow the guidelines must be developed, approved, and implemented in all cases. Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) should be immediately referred to hospitals with available primary PCI. Well-trained nurses are of the utmost importance in emergency departments, medical wards in type II and III hospitals, and intensive care units. A dedicated intensive care cardiology unit is strongly recommended in type III hospitals, whereas in lower volume hospitals, a general intensive care unit should have specific protocols to transfer patients with STEMI, cardiogenic shock, and other conditions according to prespecified protocols. In hospitals admitting patients requiring intensive cardiology care, the presence of at least 1 cardiologist certified in acute cardiac care is strongly recommended.115–118,145,199,224,255,290–293

Outcomes include mortality related to STEMI and ACS (Table 5). Local safety controls should focus on antithrombotic complications. Table 10 shows selected performance metrics to improve outcomes in acute cardiac care.

Acute Cardiac Care Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Intensive and acute cardiac care | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | 4-5 ICCU beds/100 000 inhabitants | 199 |

| Desired technology | Intensive care environment technology | 199 |

| Staffing | All nurses with > 1 year cardiology experience. Experience in acute cardiac care | 199 |

| At least 1 cardiologist certified in acute coronary care (optimal, 1/3-4 beds) | 199 | |

| Cardiologist on call 24 h (recommended in hospitals, > 300 000) | 199 | |

| Accreditation | At least 1 cardiologist accredited in acute cardiac care | 199 |

| Any accreditation conferred by any external organizations | 199 | |

| Patient services | Regional network for STEMI and other ACS | 115 |

| Cath lab available 24/7 | 115 | |

| Bundle of care treatment for sudden death (includes temperature management) | 145 | |

| Risk stratification (GRACE, TIMI, CRUSADE) | 115–118,224 | |

| Process of delivery of care for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and patient education | ||

| Local protocols based on ESC/AHA-ACC guidelines | STEMI and non-STEMI protocols | 115–118 |

| Optimal medical treatments according to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | 115–118 | |

| Multidisciplinary protocols | Prehospital systems, emergency department, cardiac unit. | 115–118 |

| Heart failure: Cardiac unit, internal medicine, emergency department | 291,292 | |

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in Table 5 | |

| Quality controls | ||

| Adherence to ESC/AHA-ACC guidelines | Patients with primary PCI in STEMI: > mean value in national registriesTime to call-door-balloon/lytic: < 60min after STEMI diagnosisFibrinolytic therapy < 30min after STEMI diagnosisPatients with dual antiplatelet therapy in ACS: > mean value in national registriesPatients with statins at discharge: > mean value in national registriesAspirin at admission: > mean value in national registries | 115–118 |

| Safety | Infections: recommended < mean value in national registriesTransfusions: recommended < mean value in national registries | 115–118,293 |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; ICCU, intensive coronary care unit; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

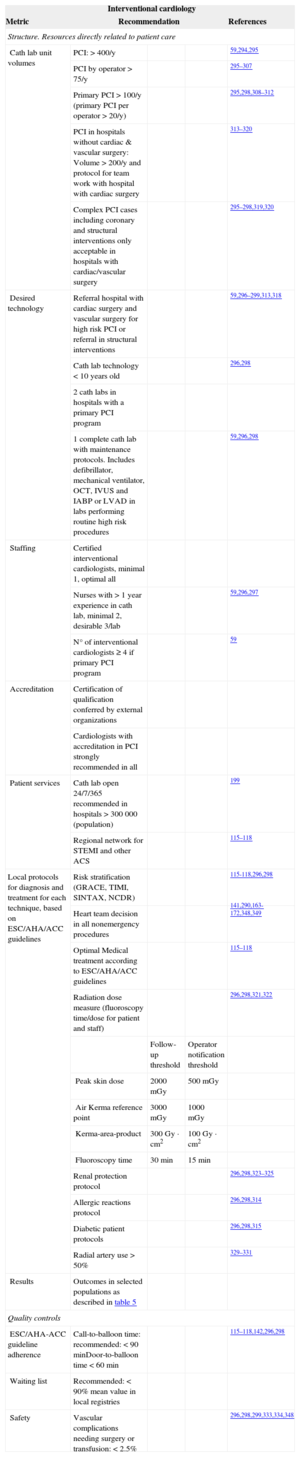

The results of PCI are highly dependent on the expertise and training of interventional cardiologists, as well as on the volume of procedures performed at each hospital and by individual interventional cardiologists. Fellow-in-training activity may have a negative impact on both outcomes and therefore local laws and regulations must be strictly followed. This may have legal implications. Accreditation should be considered in all cases. In general, complex cases should only be treated in hospitals with cardiac surgery support.319 Low-volume, highly-complex interventions (transcatheter aortic valve implantation, closure of left atrial appendage and foramen ovale, valvular and adult congenital heart disease interventions) should be permitted only in selected type III hospitals with specific training and accreditation. Adherence to local protocols based on guidelines and heart team decisions for nonurgent interventions should be considered in all cases.115–118,139,140,294–349

Outcome metrics include STEMI and ACS mortality, as well as transcatheter aortic valve implantation mortality and elective PCI mortality. The main safety control is focused on bleeding, renal failure, stroke and vascular complications requiring surgery or extended length of stay (Table 11).

Interventional Cardiology Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Interventional cardiology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References | ||

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||||

| Cath lab unit volumes | PCI: > 400/y | 59,294,295 | ||

| PCI by operator > 75/y | 295–307 | |||

| Primary PCI > 100/y (primary PCI per operator > 20/y) | 295,298,308–312 | |||

| PCI in hospitals without cardiac & vascular surgery: Volume > 200/y and protocol for team work with hospital with cardiac surgery | 313–320 | |||

| Complex PCI cases including coronary and structural interventions only acceptable in hospitals with cardiac/vascular surgery | 295–298,319,320 | |||

| Desired technology | Referral hospital with cardiac surgery and vascular surgery for high risk PCI or referral in structural interventions | 59,296–299,313,318 | ||

| Cath lab technology < 10 years old | 296,298 | |||

| 2 cath labs in hospitals with a primary PCI program | ||||

| 1 complete cath lab with maintenance protocols. Includes defibrillator, mechanical ventilator, OCT, IVUS and IABP or LVAD in labs performing routine high risk procedures | 59,296,298 | |||

| Staffing | Certified interventional cardiologists, minimal 1, optimal all | |||

| Nurses with > 1 year experience in cath lab, minimal 2, desirable 3/lab | 59,296,297 | |||

| N° of interventional cardiologists ≥ 4 if primary PCI program | 59 | |||

| Accreditation | Certification of qualification conferred by external organizations | |||

| Cardiologists with accreditation in PCI strongly recommended in all | ||||

| Patient services | Cath lab open 24/7/365 recommended in hospitals > 300 000 (population) | 199 | ||

| Regional network for STEMI and other ACS | 115–118 | |||

| Local protocols for diagnosis and treatment for each technique, based on ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Risk stratification (GRACE, TIMI, SINTAX, NCDR) | 115-118,296,298 | ||

| Heart team decision in all nonemergency procedures | 141,290,163-172,348,349 | |||

| Optimal Medical treatment according to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | 115–118 | |||

| Radiation dose measure (fluoroscopy time/dose for patient and staff) | 296,298,321,322 | |||

| Follow-up threshold | Operator notification threshold | |||

| Peak skin dose | 2000 mGy | 500 mGy | ||

| Air Kerma reference point | 3000 mGy | 1000 mGy | ||

| Kerma-area-product | 300 Gy · cm2 | 100 Gy · cm2 | ||

| Fluoroscopy time | 30 min | 15 min | ||

| Renal protection protocol | 296,298,323–325 | |||

| Allergic reactions protocol | 296,298,314 | |||

| Diabetic patient protocols | 296,298,315 | |||

| Radial artery use > 50% | 329–331 | |||

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in table 5 | |||

| Quality controls | ||||

| ESC/AHA-ACC guideline adherence | Call-to-balloon time: recommended: < 90 minDoor-to-balloon time < 60 min | 115–118,142,296,298 | ||

| Waiting list | Recommended: < 90% mean value in local registries | |||

| Safety | Vascular complications needing surgery or transfusion: < 2.5% | 296,298,299,333,334,348 | ||

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; IABT, intra-aortic balloon pump; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

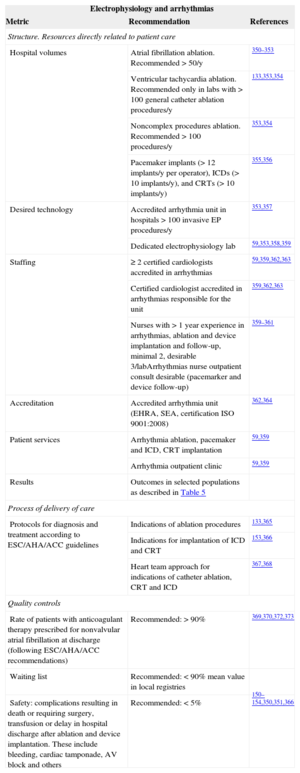

Interventional treatment of complex arrhythmias requires accreditation of both the laboratory and interventional cardiologists. Indications for catheter ablation and other techniques including cardiac resynchronization therapy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation are rapidly changing. Ablation procedures in some arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation) are increasing rapidly without proper evidence of benefit in clinical trials. In all cases, the indication should be established after a heart team approach that adheres to the guideline recommendations. Again, accreditation of units and staff is crucial for outcomes and proper legislation should regulate the activity and level of responsibility of fellows in training (Table 12).150–152,331,350–373

Electrophysiology and Complex Arrhythmias Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Electrophysiology and arrhythmias | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | Atrial fibrillation ablation. Recommended > 50/y | 350–353 |

| Ventricular tachycardia ablation. Recommended only in labs with > 100 general catheter ablation procedures/y | 133,353,354 | |

| Noncomplex procedures ablation. Recommended > 100 procedures/y | 353,354 | |

| Pacemaker implants (> 12 implants/y per operator), ICDs (> 10 implants/y), and CRTs (> 10 implants/y) | 355,356 | |

| Desired technology | Accredited arrhythmia unit in hospitals > 100 invasive EP procedures/y | 353,357 |

| Dedicated electrophysiology lab | 59,353,358,359 | |

| Staffing | ≥ 2 certified cardiologists accredited in arrhythmias | 59,359,362,363 |

| Certified cardiologist accredited in arrhythmias responsible for the unit | 359,362,363 | |

| Nurses with > 1 year experience in arrhythmias, ablation and device implantation and follow-up, minimal 2, desirable 3/labArrhythmias nurse outpatient consult desirable (pacemarker and device follow-up) | 359–361 | |

| Accreditation | Accredited arrhythmia unit (EHRA, SEA, certification ISO 9001:2008) | 362,364 |

| Patient services | Arrhythmia ablation, pacemaker and ICD, CRT implantation | 59,359 |

| Arrhythmia outpatient clinic | 59,359 | |

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in Table 5 | |

| Process of delivery of care | ||

| Protocols for diagnosis and treatment according to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Indications of ablation procedures | 133,365 |

| Indications for implantation of ICD and CRT | 153,366 | |

| Heart team approach for indications of catheter ablation, CRT and ICD | 367,368 | |

| Quality controls | ||

| Rate of patients with anticoagulant therapy prescribed for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation at discharge (following ESC/AHA/ACC recommendations) | Recommended: > 90% | 369,370,372,373 |

| Waiting list | Recommended: < 90% mean value in local registries | |

| Safety: complications resulting in death or requiring surgery, transfusion or delay in hospital discharge after ablation and device implantation. These include bleeding, cardiac tamponade, AV block and others | Recommended: < 5% | 150–154,350,351,366 |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; AV, atrioventricular; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; EHRA, European Heart Rhythm Association; EP: electrophysiology procedures; SEA, Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

Outcomes targets should include complex electrophysiological procedures and device implantation mortality. Safety should focus on complications requiring surgery, transfusions, or prolongation of hospitalization.

Complex invasive electrophysiological procedures may be defined as procedures performed by < 50% of the country's laboratories, including150,350,351,354 ventricular tachycardia catheter ablation, atrial fibrillation catheter ablation, left atrial tachycardia/flutter ablation, percutaneous/surgical epicardial procedures, and referred procedures after failure in other centers.

Noncomplex invasive electrophysiological procedures include catheter ablation of the different substrates in regular paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, common atrial flutter, and atrio-ventricular junction nodal ablation.

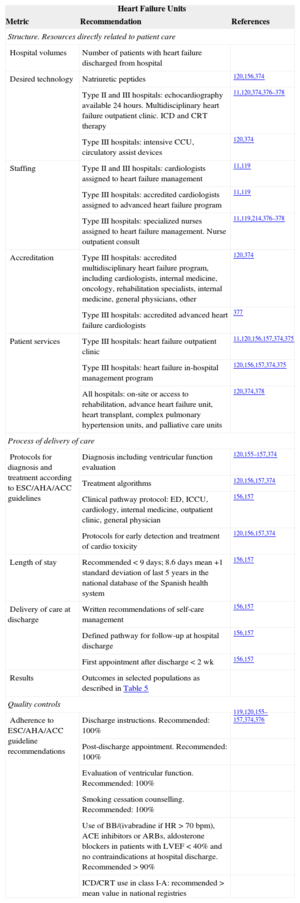

Heart Failure Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical PracticeDiagnosis and treatment of HF are rapidly changing and increasing in complexity, and adherence to guidelines is likely to ensure better outcomes including survival. Many patients require treatment before hospital admission. Most present with comorbidities that require specific treatment and cardiac care must be continued after discharge of the patient from the hospital in all cases. Teamwork as opposed to admitting patients in cardiology or internal medicine is crucial and strongly recommended. Some type of HF unit is strongly recommended in all hospitals. Outcomes include mortality and hospital readmissions. The recommendations in Table 13 apply to all hospitals unless stated otherwise.11,60,67,119,120,156–158,214,246,374–378

Heart Failure Unit Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Heart Failure Units | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | Number of patients with heart failure discharged from hospital | |

| Desired technology | Natriuretic peptides | 120,156,374 |

| Type II and III hospitals: echocardiography available 24 hours. Multidisciplinary heart failure outpatient clinic. ICD and CRT therapy | 11,120,374,376–378 | |

| Type III hospitals: intensive CCU, circulatory assist devices | 120,374 | |

| Staffing | Type II and III hospitals: cardiologists assigned to heart failure management | 11,119 |

| Type III hospitals: accredited cardiologists assigned to advanced heart failure program | 11,119 | |

| Type III hospitals: specialized nurses assigned to heart failure management. Nurse outpatient consult | 11,119,214,376–378 | |

| Accreditation | Type III hospitals: accredited multidisciplinary heart failure program, including cardiologists, internal medicine, oncology, rehabilitation specialists, internal medicine, general physicians, other | 120,374 |

| Type III hospitals: accredited advanced heart failure cardiologists | 377 | |

| Patient services | Type III hospitals: heart failure outpatient clinic | 11,120,156,157,374,375 |

| Type III hospitals: heart failure in-hospital management program | 120,156,157,374,375 | |

| All hospitals: on-site or access to rehabilitation, advance heart failure unit, heart transplant, complex pulmonary hypertension units, and palliative care units | 120,374,378 | |

| Process of delivery of care | ||

| Protocols for diagnosis and treatment according to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Diagnosis including ventricular function evaluation | 120,155–157,374 |

| Treatment algorithms | 120,156,157,374 | |

| Clinical pathway protocol: ED, ICCU, cardiology, internal medicine, outpatient clinic, general physician | 156,157 | |

| Protocols for early detection and treatment of cardio toxicity | 120,156,157,374 | |

| Length of stay | Recommended < 9 days; 8.6 days mean +1 standard deviation of last 5 years in the national database of the Spanish health system | 156,157 |

| Delivery of care at discharge | Written recommendations of self-care management | 156,157 |

| Defined pathway for follow-up at hospital discharge | 156,157 | |

| First appointment after discharge < 2 wk | 156,157 | |

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in Table 5 | |

| Quality controls | ||

| Adherence to ESC/AHA/ACC guideline recommendations | Discharge instructions. Recommended: 100% | 119,120,155–157,374,376 |

| Post-discharge appointment. Recommended: 100% | ||

| Evaluation of ventricular function. Recommended: 100% | ||

| Smoking cessation counselling. Recommended: 100% | ||

| Use of BB/(ivabradine if HR > 70 bpm), ACE inhibitors or ARBs, aldosterone blockers in patients with LVEF < 40% and no contraindications at hospital discharge. Recommended > 90% | ||

| ICD/CRT use in class I-A: recommended > mean value in national registries | ||

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta-blockers; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ED, emergency department, ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HR, heart rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICCU, intensive coronary care unit.

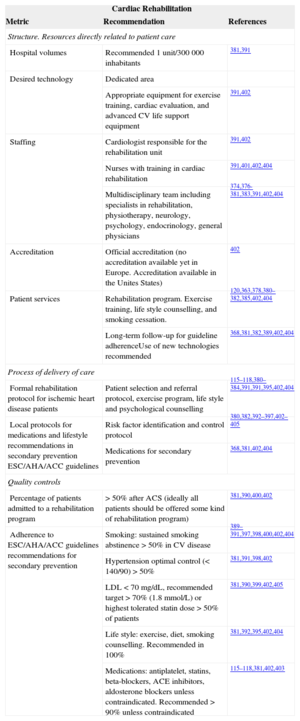

Cardiac rehabilitation is more than controlled exercise training. The main objective should be patient education for long-term changes related to lifestyle, adherence to medical treatment for the specific condition, and use of appropriate secondary prevention strategies. In many cases cardiac rehabilitation is neglected, especially for long-term secondary prevention. Cardiac rehabilitation units or programs should be implemented to offer all patients appropriate counselling and follow-up for secondary prevention. Teamwork, especially with general physicians, is essential (Table 14).115,379–405

Cardiac Rehabilitation Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Cardiac Rehabilitation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | Recommended 1 unit/300000 inhabitants | 381,391 |

| Desired technology | Dedicated area | |

| Appropriate equipment for exercise training, cardiac evaluation, and advanced CV life support equipment | 391,402 | |

| Staffing | Cardiologist responsible for the rehabilitation unit | 391,402 |

| Nurses with training in cardiac rehabilitation | 391,401,402,404 | |

| Multidisciplinary team including specialists in rehabilitation, physiotherapy, neurology, psychology, endocrinology, general physicians | 374,376-381,383,391,402,404 | |

| Accreditation | Official accreditation (no accreditation available yet in Europe. Accreditation available in the Unites States) | 402 |

| Patient services | Rehabilitation program. Exercise training, life style counselling, and smoking cessation. | 120,363,378,380–382,385,402,404 |

| Long-term follow-up for guideline adherenceUse of new technologies recommended | 368,381,382,389,402,404 | |

| Process of delivery of care | ||

| Formal rehabilitation protocol for ischemic heart disease patients | Patient selection and referral protocol, exercise program, life style and psychological counselling | 115–118,380–384,391,391,395,402,404 |

| Local protocols for medications and lifestyle recommendations in secondary prevention ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Risk factor identification and control protocol | 380,382,392–397,402–405 |

| Medications for secondary prevention | 368,381,402,404 | |

| Quality controls | ||

| Percentage of patients admitted to a rehabilitation program | > 50% after ACS (ideally all patients should be offered some kind of rehabilitation program) | 381,390,400,402 |

| Adherence to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines recommendations for secondary prevention | Smoking: sustained smoking abstinence >50% in CV disease | 389–391,397,398,400,402,404 |

| Hypertension optimal control (< 140/90) > 50% | 381,391,398,402 | |

| LDL < 70 mg/dL, recommended target > 70% (1.8 mmol/L) or highest tolerated statin dose > 50% of patients | 381,390,399,402,405 | |

| Life style: exercise, diet, smoking counselling. Recommended in 100% | 381,392,395,402,404 | |

| Medications: antiplatelet, statins, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, aldosterone blockers unless contraindicated. Recommended >90% unless contraindicated | 115–118,381,402,403 | |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; CV, cardiovascular; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LDL, low-density lipoproteins.

Quality controls should include access to rehabilitation programs for all patients with ischemic heart disease and adherence to guidelines during long-term follow-up.

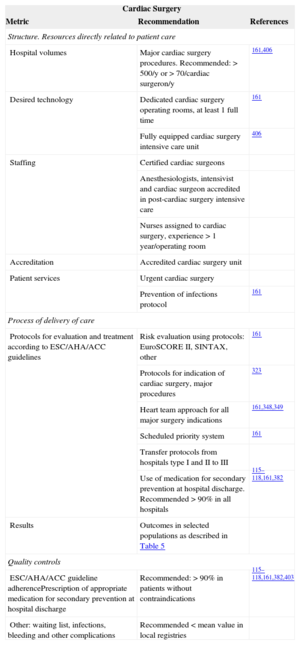

Cardiac Surgery Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical PracticeCardiac surgery is closely related to clinical cardiology and team work between both specialties is, without exception, essential. Interstingly, quality controls in cardiac surgery have been implemented in many hospitals in some countries in the past few years. Hospital volumes and the training and expertise of surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and referring cardiologists have a strong impact on outcomes (Table 15).161,406–421

Cardiac Surgery Performance Measures Related to Better Results in Clinical Practice

| Cardiac Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Recommendation | References |

| Structure. Resources directly related to patient care | ||

| Hospital volumes | Major cardiac surgery procedures. Recommended: > 500/y or > 70/cardiac surgeron/y | 161,406 |

| Desired technology | Dedicated cardiac surgery operating rooms, at least 1 full time | 161 |

| Fully equipped cardiac surgery intensive care unit | 406 | |

| Staffing | Certified cardiac surgeons | |

| Anesthesiologists, intensivist and cardiac surgeon accredited in post-cardiac surgery intensive care | ||

| Nurses assigned to cardiac surgery, experience > 1 year/operating room | ||

| Accreditation | Accredited cardiac surgery unit | |

| Patient services | Urgent cardiac surgery | |

| Prevention of infections protocol | 161 | |

| Process of delivery of care | ||

| Protocols for evaluation and treatment according to ESC/AHA/ACC guidelines | Risk evaluation using protocols: EuroSCORE II, SINTAX, other | 161 |

| Protocols for indication of cardiac surgery, major procedures | 323 | |

| Heart team approach for all major surgery indications | 161,348,349 | |

| Scheduled priority system | 161 | |

| Transfer protocols from hospitals type I and II to III | ||

| Use of medication for secondary prevention at hospital discharge. Recommended > 90% in all hospitals | 115–118,161,382 | |

| Results | Outcomes in selected populations as described in Table 5 | |

| Quality controls | ||

| ESC/AHA/ACC guideline adherencePrescription of appropriate medication for secondary prevention at hospital discharge | Recommended: > 90% in patients without contraindications | 115–118,161,382,403 |

| Other: waiting list, infections, bleeding and other complications | Recommended < mean value in local registries | |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Outcomes are relatively easy to measure and should focus on mortality and length of hospital stay in prevalent, well-defined surgical procedures such as staged, first-time coronary artery bypass grafting, and aortic and mitral valve surgery.

CURRENT LIMITATIONSInformation CaptureDatabases currently used for benchmarking may not have the appropriate quality and all derived information will be misleading, causing a substantial negative impact on scientific and public opinion. Audited prospective mandatory reports would arguably be the best way to capture simple, but at the same time, essential/core information. Dedicated data registries (eg, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, STEMI, PCI, arrhythmia ablation registries) may include more detailed and specific information, but their validation will depend on the universal inclusion of patients and the quality of the audits. However, even in prospective registries, some patients could be missed. This could be even more likely in the sickest patients or those who die soon after admission, illustrating the need for serious and detailed audits.422 Retrospective data collection may yield a different type of information. Voluntary registries including a selected number of patients may not represent true values for benchmarking.

Coding of Clinical Diagnosis and EventsInternational Classification of Diseases codes are universally accepted but do not clearly allow the identification of DRGs perceived to be of the upmost importance in modern cardiology and must be periodically adapted to properly capture changes in clinical practice. One example is the lack of specific codes for STEMI and other types of myocardial infarction,113 a diagnose that is currently included in most quality control programs; another example is the lack of appropriate codes to differentiate a simple episode of ventricular fibrillation resolved with an electric shock from a complex cardiac arrest in a patient admitted unconscious to the hospital. Future editions (ICD-10 and subsequent) should include the appropriate coding required for quality assessment standards in contemporary clinical practice.

Diagnosis itself may not be as reliable as desirable. Diagnosis of HF leads to a significant number of false positive and negative interpretations (typically, hospitalization for HF is difficult to adjudicate in clinical trials).40,173–176,413,414 The same is true for relevant, high prevalent conditions that require central adjudication in major clinical trials to overcome the different interpretation of clinical data at the local level. These include stroke, myocardial infarction, major bleeding, and cardiovascular mortality, among other conditions.422

FUTURE CHALLENGESQuality measures, especially outcome metrics, should be transparent and, to avoid confusion in benchmarking, a universally accepted standardization is necessary. This will require collaboration and agreement between scientific societies, medical organizations, and health care authorities. The following fields need future refinement and represent a clear unmet need and an opportunity for improvement: a) standardization of data (data capture and availability, risk corrections, target values and reporting); b) standardization of audits to ascertain the quality of data; c) participation of all hospitals regulated by health care authorities; d) identification and definition of quality metrics for outpatient clinical practice423–425 and long-term follow-up; e) identification and definition of perceived quality measures; f) inclusion of cost-effectiveness measures, and g) improvement of reliability by refinement of the quality metrics and controls considering the feedback from participants in benchmarking programs.