To determine whether mortality from acute myocardial infarction has reduced in Spain and the possibly related therapeutic factors.

MethodsNine thousand, nine hundred and forty-nine patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction admitted to the Coronary Care Unit were identified from PRIAMHO I, II and MASCARA registries performed in 1995, 2000 and 2005, with a 6 month follow-up.

ResultsFrom 1995 to 2005 patients were increasingly more likely to have hypertension, hyperlipidemia and anterior infarction, but age of onset and the proportion of females did not increase. Twenty-eight-day mortality rates were 12.6%, 12.3% and 6% in 1995, 2000 and 2005 respectively, and 15.3%, 14.6% and 9.4% at 6 months (both P-trend <.001). Multivariate analysis was performed and the adjusted odds ratio for 28-day mortality for an infarction occuring in 2005 (compared with 1995) was 0.62 (95% confidence interval: 0.44-0.88) whereas the adjusted hazard ratio for mortality at 6 months was 0.40 (95% confidence interval: 0.24-0.67). Other variables independently associated with lower mortality at 28 days were: reperfusion therapy, and the use of anti-thrombotic treatment, beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. The 28-day-6-month period had an independent protective effect on the following therapies: coronary reperfusion, and prescription of antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers and lipid lowering drugs upon discharge.

ConclusionsTwenty-eight-day and six-month mortality rates fell among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in Spain from 1995 to 2005. The possibly related therapeutic factors were the following: more frequent reperfusion therapy and increased use of anti-thrombotic drugs, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and lipid lowering drugs.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONThe health care provided to patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has greatly changed during the past two decades, with the advent of new diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. As a result, mortality has decreased, as has been demonstrated in several international registries.1, 2, 3 These advances endorsed by scientific evidence, have been incorporated by successive good practice guidelines (GPC)4, 5 implying that if the guidelines are closely followed, a lower mortality can be achieved.6, 7

Mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) very much depends on how early the ischemic myocardium is reperfused, and amongst the available options, primary angioplasty has proven to be better than fibrinolysis.8 However, it is not as frequently used in Spain as in other western countries.9 Furthermore, many other effective therapies recommended by guidelines could also be employed more.1, 7

National registries enable us to monitor disease treatment changes and how they may affect mortality. In Spain, the PRIAMHO I, II and MASCARA registries collected AMI patient data for 1995, 2000 and 2005, respectively.10, 11, 12

The aims of this paper are: a) to analyze the changes in 28-day and 6-month mortality in patients with STEMI from 1995 to 2005, and b) to determine which therapeutic factors are associated with this variation.

METHODSThe methodology used by the PRIAMHO I, II and MASCARA registries has already been described in detail.10, 11, 12 In summary, the PRIAMHO registries, designed by the Sección de Cardiopatía Isquémica y Unidades Coronarias de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (Department of Ischaemic Heart Diseases and Coronary Care Units from the Spanish Society of Cardiology) registered all patients with and without STEMI admitted to the coronary care unit/cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) between October 1994 and September 1995 and from 15 May to 16 December 2000. Forty-seven hospitals participated in the PRIAMHO I and 81 in PRIAMHO II. All hospitals had to meet the following requirements: a) register at least 70% of AMI patients admitted to the hospital; b) register at least 75% of the AMI patients admitted to the CICU; c) reach a Kappa concordance index above 70% between the data registered and data obtained by an external auditor from a random sample of 15% of the patients, and d) perform follow-up after one year for more than 90% of the registered patients.

The MASCARA study12 broadened the patient type analyzed to all acute coronary syndromes with and without AMI, and also included patients that were not admitted to the CICU. The recruitment period was from September 2004 to June 2005. Sixty hospitals were chosen at random in accordance with the hospital's attendance. Between 2005 and 2006 an exhaustive inclusion control was performed. The study excluded hospitals whose inclusion rate was lower than 50% that expected in accordance with the health centre's attendance rate and whose 95% confidence interval (CI) for each acute coronary syndrome type mortality rate was not within the mean range of the reference centers. As such, 18 out of the 50 centers that had completed the recruitment were excluded.

For our study, we have chosen the STEMI patient subgroup admitted to the CICU from the PRIAMHO I, II and MASCARA study. Of those patients in the CICU, those with ST-segment elevation were identified among those who met the AMI criteria. AMI diagnosis was based on the definition that existed when the study took place.13, 14 Data was recorded for: demographics, clinical history, characteristics of the acute event and complications, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures used in the CICU and drug treatment upon discharge. Follow-up was performed in an outpatient clinic or by telephone. Mortality data was collected for any cause.

Statistical AnalysisPatient characteristics are expressed as mean±standard deviation, or frequency and percentage. For the bivariate analysis, the χ2 test, Student's-t test or Mann-Whitney U test were used, depending on the data distribution. When analyzing evolution over three periods, the P value is presented for linear tendency. To analyze the relationship between period and short-term mortality (28 days) logistic regression models have been used, expressing the results as odds ratio (OR), given that most deaths occur during the first 24h and these data are better adjusted to a binomial distribution. To analyse the relationship between the period and time to long-term mortality (28 days-6 months) Cox's regression models have been used, expressing the results as hazard ratio (HR). The HR's linearity assumption for continuous variables is calculated using a smoothing spline regression, and the proportionality assumption is calculated by testing the interaction with time. None of these tests reached a statistical significance against these assumptions. The influential cases were analyzed using the delta-beta method, in which the variation of estimations was compared following the extraction of each of the patients.

In addition to the variable ‘period’, with 1995 as a reference, each of the models were including more and more variables regarding demographics, clinical history, acute events and lastly, diagnosis and therapeutic procedures. Variables that showed, at least, a significant marginal relationship of P<.15 were included as possible confounding factors in the bivariate analysis by comparing the surviving patients with those that died after 30 days or during the 28-day-6-month period.

We used the R: A language and environment for statistical computing program (version 2.11.0). Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

RESULTSThe PRIAMHO I and II results included 3516 and 4080 STEMI patients, respectively. Two thousand three-hundred and fifty-three STEMI patients attended to in the CICU in the MASCARA study. Therefore, this paper includes 9949 STEMI patients admitted to the CICU in 1995, 2000 and 2005.

Clinical CharacteristicsGeneral patient data are shown in Table 1. During 1995-2005, there was a significant increase in patients with hypercholesterolemia (from 28.5% to 41.9%), hypertension (from 39.8% to 48.2%), and anterior infarction (from 44.9% to 57.7%). The percentage of patients with a history of revascularization and the percentage of patients provided health care in hospitals with a catheterization laboratory also increased.

Table 1. General Data for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction Admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Included in the PRIAMHO I, PRIAMHO II and MASCARA Registers in 1995, 2000 and 2005, Respectively.

| 1995 (n=3516) | 2000 (n=4080) | 2005 (n=2353) | P-trend | |

| Age, years | 63.8±12.3 | 64.4±13.1 | 63.2±13.2 | .123 |

| Female | 735 (20.9) | 1005 (24.6) | 464 (19.8) | .703 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Diabetes | 784 (22.3) | 1133 (27.8) | 512 (21.8) | .712 |

| Tobacco use | 1467 (41.7) | 1928 (47.3) | 987 (41.9) | .388 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1002 (28.5) | 1625 (39.9) | 985 (41.9) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 1398 (39.8) | 1771 (43.5) | 1134 (48.2) | <.001 |

| Previous heart disease | ||||

| Previous heart attack | 480 (13.7) | 475 (11.7) | 272 (11.6) | .010 |

| Revascularization | 101 (2.9) | 239 (5.9) | 118 (5.0) | <.001 |

| ECG (anterior vs others) | 1580 (44.9) | 1867 (45.8) | 1069 (57.7) | <.001 |

| Catheterization laboratory | 2135 (60.7) | 2422 (59.4) | 1625 (69.1) | <.001 |

ECG, electrocardiography.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

Reperfusion treatment use gradually rose from 1995 to 2005 (60.4%, 67.0% and 72.3%) due to the increase in using primary angioplasty (Table 2). Delay in administering anti-thrombotic drugs did not significantly decrease, although the Symptom-monitoring time went from 135min in 1995 to 95min in 2005 and the door-to-needle time dropped from 60 to 43min. On the other hand, the median door-to-balloon time increased 15min between 2000 and 2005.

Table 2. Treatment for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction Admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Included in 1995, 2000 and 2005 in the PRIAMHO I, PRAIMHO II and MASCARA Registers, Respectively.

| 1995 (n=3516) | 2000 (n=4080) | 2005 (n=2353) | P-trend | |

| Reperfusion | ||||

| Thrombolysis | 2125 (60.4) | 2429 (59.7) | 1132 (48.1) | <.001 |

| Primary PTCA | -- | 298 (7.3) | 569 (24.2) | <.001 |

| Rescue PTCA | -- | 166 (4.1) | 180 (7.6) | <.001 |

| Symptom-monitoring time | 135 [60-300] | 120 [60-265] | 95 [45-202] | <.001 |

| Symptom-thrombolysis time | 180 (120-264) | 170 (115-255) | 164 (96-288) | .191 |

| Door-to-needle time | 60 [30-93] | 47 [30-76] | 43 [25-75] | .001 |

| Door-to-balloon time | -- | 80 [50-127] | 95 [60-179] | <.001 |

| Drug treatment | ||||

| Antiplatelet agents | 3190 (90.7) | 3925 (96.5) | 2266 (96.3) | <.001 |

| Clopidogrel | -- | 296 (7.3) | 1455 (61.8) | <.001 |

| GPIIb-IIa antagonists | -- | 387 (9.5) | 722 (30.7) | <.001 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 2274 (64.7) | 2503 (62.1) | 432 (18.4) | <.001 |

| LMWH | -- | 1695 (42.4) | 1664 (70.7) | <.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 1109 (31.5) | 2078 (51.1) | 1712 (82.1) | <.001 |

| ACEI/ARB-II | 893 (25.4) | 1757 (43.2) | 1522 (73) | <.001 |

| Lipid lowering drugs | -- | 745 (18.3) | 1682 (80.7) | <.001 |

| Nitrates (taken orally or applied to skin) | 1110 (31.6) | 1217 (30.7) | 1101 (52.8) | <.001 |

| IV nitrates | 2544 (72.4) | 2782 (70.2) | 1528 (73.3) | .749 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 389 (11.1) | 250 (6.2) | 246 (11.8) | .577 |

| Procedures | ||||

| Coronary angiography | 258 (7.3) | 677 (16.8) | 935 (39.9) | <.001 |

| Echocardiography | 1464 (41.6) | 1405 (34.9) | 2010 (85.4) | <.001 |

| Swan-Ganz catheter | 210 (6.0) | 134 (3.3) | 74 (3.2) | <.001 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB-II, angiotensin II receptor blockers; GPIIb-IIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; IV, intravenous; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Anti-thrombotic treatment used in the CICU changed greatly from 2000, when the double/triple antiplatelet therapy was introduced and low molecular weight heparin was used almost globally. Administration of beta-blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptors blockers (ARB-II), lipid lowering drugs and nitrates also significantly increased.

The diagnostic and therapeutic procedures used in CICU are also shown in Table 2. Coronary angiography went from 7.3% in 1995 to 39.9% in 2005 and echocardiography from 41.6% to 85.4%. On the contrary, Swan-Ganz catheterization was used less frequently.

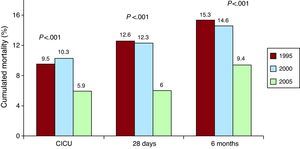

Clinical Evolution in the Cardiac Intensive Care UnitLess patients developed severe heart failure (Killip class III/IV), which lowered in 2005 (11.3%), compared to 1995 and 2000 (13.5% and 16.1%) without reaching statistical significance (Table 3). The incidence of atrial fibrillation and mechanical complications significantly reduced, while AMI relapses did not increase despite there being more patients with post-infarction angina. Mortality in the CICU decreased from 9.5% in 1995 to 5.9% in 2005 (P<.001), as is shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3. Clinical Evolution for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction Admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Included in 1995, 2000 and 2005 in the PRIAMHO I, PRAIMHO II and MASCARA Registers, Respectively.

| 1995 (n=3516) | 2000 (n=4080) | 2005 (n=2353) | P-trend | |

| Complications | ||||

| Maximum Killip class III/IV | 475 (13.5) | 654 (16.1) | 265 (11.3) | .078 |

| AMI relapse | 118 (3.4) | 97 (2.4) | 66 (2.8) | .133 |

| post-AMI angina | 323 (9.2) | 322 (8.0) | 273 (11.6) | .008 |

| Primary VF | 191 (5.4) | 259 (6.5) | 147 (6.2) | .145 |

| Sustained VT | 322 (9.2) | 133 (3.3) | 171 (7.3) | <.001 |

| Advanced AVB in CICU | 207 (5.9) | 295 (7.4) | 150 (6.4) | .293 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 307 (8.7) | 324 (8.1) | 90 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Mechanical complications | 119 (3.4) | 131 (3.3) | 26 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Mortality | 333 (9.5) | 419 (10.3) | 139 (5.9) | <.001 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AVB, atrioventricular block; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 1. Cumulated mortality in the cardiac intensive care unit, at 28 days and at 6 months for patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction, admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit, included in 1995, 2000 and 2005 in the PRIAMHO I, PRAIMHO II and MASCARA registers, respectively (P-trend). CICU, cardiac intensive care unit.

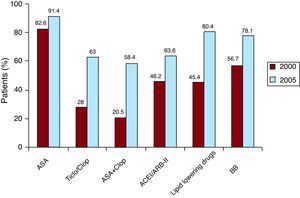

Treatment Upon DischargeFigure 2 shows the drugs with type I recommendations in the GPC. We have only provided data for 2000 and 2005 because data on this matter was not collected in 1995. There was a significant increase in all of the therapies analyzed.

Figure 2. Treatment upon discharge from the hospital for patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction, admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit, included in the PRIAMHO II and MASCARA registers respectively in 2000 and 2005 (this data was not included in 1995). All differences reached statistical significance (P<.001). ACEI/ARB-II, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; BB, beta-blockers; Ticlo/Clop, Ticlopidine/clopidogrel.

Twenty-Eigh-Day and Six-Month Mortality and Related FactorsMortality significantly decreased between 1995 and 2005: at 28 days (12.6%, 12.3%, 6%) and at 6 months (15.3%, 14.6%, 9.4%) as shown in Figure 1.

Table 4 shows the 28-day mortality determinants. This is associated with age, female sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, previous heart attack, Q-wave heart attack, delay in monitoring, anterior infarction, reinfarction, and Killip class III/IV. Early reperfusion and reperfusion were significantly related to a decrease in mortality, as were tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, using anti-thrombotic drugs, BB, ACEI/ARB-II and lipid lowering drugs in the CICU, and coronary angiography.

Table 4. Determining Factors for 28-Day and 6-Month Mortality for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction, Admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Included in 1995, 2000 and 2005 in the PRIAMHO I, PRIAMHO II and MASCARA Registers, Respectively.

| Survivors (n=8863) | Death within 28 days (n=1086) | P | |

| Age, years | 62.8±12.7 | 72.7±10.7 | <.001 |

| Female | 1798 (20.3) | 407 (37.5) | <.001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2045 (23.1) | 384 (35.4) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 4108 (46.4) | 274 (25.3) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3320 (37.5) | 292 (26.9) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 3785 (42.7) | 518 (47.7) | .002 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Previous heart attack | 1040 (11.7) | 187 (17.2) | <.001 |

| History of revascularization | 403 (4.5) | 55 (5.1) | .484 |

| Q-wave heart attack | 7572 (85.5) | 966 (89.1) | .001 |

| Anterior AMI vs others | 3930 (46.7) | 586 (56.6) | <.001 |

| Symptom-monitoring time | 120 [60-246] | 164 [65-384] | <.001 |

| Maximum Killip class III/IV | 688 (7.8) | 706 (65.4) | <.001 |

| AMI relapse in CICU | 202 (2.3) | 79 (7.3) | <.001 |

| Post-AMI angina in CICU | 827 (9.4) | 91 (8.4) | .318 |

| Treatments and procedures | |||

| Thrombolysis and/or PTCA | 5961 (67.3) | 567 (52.3) | <.001 |

| Time to reperfusion | |||

| <3 h | 2387 (31.6) | 171 (17.6) | <.001 |

| 3-6 h | 1659 (22.0) | 181 (18.6) | |

| >6h–12h | 487 (6.4) | 80 (8.2) | |

| No reperfusion or >12 h | 3024 (40.0) | 542 (55.6) | |

| Antiplatelet agents in CICU | 8472 (95.7) | 909 (83.8) | <.001 |

| Clopidogrel in CICU | 1674 (29.0) | 77 (12.1) | <.001 |

| GPIIb-IIIa antagonists in CICU | 1047 (18.1) | 62 (9.7) | <.001 |

| UFH in CICU | 4699 (53.3) | 510 (47.1) | <.001 |

| LMWH in CICU | 3115 (54.5) | 244 (38.6) | <.001 |

| Betablockers in CICU | 4715 (54.7) | 184 (17.5) | <.001 |

| ACEI/ARB-II in CICU | 3874 (45.0) | 298 (28.3) | <.001 |

| Lipid lowering drugs in CICU | 2353 (42.5) | 74 (12.2) | <.001 |

| Coronary angiography in CICU | 1693 (19.2) | 177 (16.4) | .025 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB-II, angiotensin II receptor blockers; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; GPIIb/IIIa, glycoproteins IIb/IIIa; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

Several logistic regression models were carried out (Table 5), and for each one we added more potential confounding variables. A significantly lower mortality was shown for all of them in 2005, compared with 1995, and this decrease was independent of the variables with most impact on mortality, such as age, sex, diabetes, reperfusion therapy, and Killip class III/IV. Other factors with a protective effect are: reperfusion therapy and anti-thrombotic drugs, BB, and ACEI/ARB-II administered in CICU. The risk of dying rose with age, female sex, anterior infarction and above all, the Killip class III/IV.

Table 5. Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Interval of 28-Day Mortality for the Admission Period Adjusted for Potentially Confounding Demographic, Clinical and Treatment Factors for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Period | ||||

| 1995 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 2000 | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.78 (0.66-0.93) | 1.15 (0.96-1.39) |

| 2005 | 0.43 (0.35-0.53) | 0.45 (0.37–0.56) | 0.33 (0.25–0.43) | 0.62 (0.44-0.88) |

| Adjustment variables | ||||

| Age | 1.07 (1.07-1.08) | 1.07 (1.06–1.08) | 1.06 (1.05-1.07) | 1.05 (1.04-1.06) |

| Female sex | 1.47 (1.27-1.71) | 1.44 (1.25–1.67) | 1.25 (1.04-1.50) | 1.28 (1.06-1.55) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.41 (1.22-1.63) | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | 1.06 (0.89-1.26) | 1.12 (0.93-1.35) |

| AHT | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) | 0.92 (0.80–1.05) | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) | 0.94 (0.79-1.12) |

| Previous AMI/ revascularization. | 1.43 (1.21-1.70) | 1.46 (1.23-1.73) | 1.12 (0.91-1.38) | 1.16 (0.93-1.44) |

| Q-wave heart attack | -- | 1.51 (1.23–1.87) | 1.33 (1.04-1.70) | 1.36 (1.05-1.76) |

| Primary thrombolysis/reperfusion. | -- | 0.73 (0.64–0.84) | 0.77 (0.65-0.91) | 0.84 (0.70-0.99) |

| Anterior AMI | -- | -- | 1.19 (1.02–1.40) | 1.58 (1.33-1.87) |

| Max. Killip class III/IV | -- | -- | 17.64 (14.99-20.75) | 16.8 (14.0-20.1) |

| ASA/Clopidogrel/ GPIII/IV antagonists in CICU | 0.38 (0.28-0.5) | |||

| UFH/LMWH in CICU | 0.67 (0.56-0.82) | |||

| Betablockers in CICU | 0.48 (0.39-0.59) | |||

| ACEI/ARB-II in CICU | 0.35 (0.29-0.43) | |||

| Model deviance | 5491.9 | 5466.1 | 4201.2 | 3927.7 |

| P * | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AHT, arterial hypertension; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB-II, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; GPIII/IV, glycoproteins III/IV; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

* Compared with the 2000 model.

Table 5 shows that the lower mortality of 2000 (as compared to 1995) disappeared in model 4. This is because anti-thrombotic treatment, BB and ACEI/ARB-II were introduced to CICU. On the other hand, the protective effects of 2005 remained.

The 28-day-6-month mortality-related factors are shown in Table 6. The following factors had a significant relationship with risk of dying at 28-days: age, female sex, diabetes, hypertension, previous heart attack, maximum Killip class, AMI relapses and post-infarction angina. On the contrary, the following were related to lower mortality: tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, early reperfusion, administering antiplatelets agents, BB and lipid lowering drugs upon discharge, and performing a coronary angiography during the hospital stay.

Table 6. Determining Factors for 28-Day-6-Month Mortality for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction, Admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and Included in 1995, 2000 and 2005 in the PRIAMHO I, PRIAMHO II and MASCARA Registers (Survivors at 28 Days).

| Survivors (n=8652) | Death between 28 days and 6 months (n=211) | P | |

| Age, years | 62.6±12.6 | 72.4±10.8 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 1736 (20.1) | 62 (29.4) | .001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1971 (22.8) | 74 (35.1) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 4047 (46.8) | 61 (28.9) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3258 (37.7) | 62 (29.4) | .017 |

| Hypertension | 3665 (42.4) | 120 (56.9) | <.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Previous heart attack | 1002 (11.6) | 38 (18.0) | .006 |

| History of revascularization | 395 (4.6) | 8 (3.8) | .713 |

| Q-wave heart attack | 7398 (85.6) | 174 (82.5) | .242 |

| Anterior AMI vs others | 3824 (46.6) | 106 (52.5) | .113 |

| Symptom-monitoring time | 120 [60-244] | 150 [76.5-304] | .016 |

| Maximum Killip class III/IV | 627 (7.27) | 61 (28.9) | <.001 |

| AMI relapse in CICU | 191 (2.2) | 11 (5.2) | .009 |

| Post-AMI angina in CICU | 796 (9.3) | 31 (14.7) | .011 |

| Treatments and procedures | |||

| Thrombolysis/Primary reperfusion | 5856 (67.7) | 105 (49.8) | <.001 |

| Time to reperfusion | |||

| <3 h | 2356 (32.0) | 31 (16.4) | <.001 |

| 3h–6h | 1620 (22.0) | 39 (20.6) | |

| >6h–12h | 476 (6.5) | 11 (5.8) | |

| No reperfusion or >12h | 2916 (39.6) | 108 (57.1) | |

| ASA upon discharge * | 4922 (87.2) | 96 (71.6) | <.001 |

| Ticlopidine/Clopidogrel upon discharge * | 2368 (42.0) | 38 (28.4) | .002 |

| Beta-blockers upon discharge * | 3750 (66.5) | 36 (26.9) | <.001 |

| ACEI/ARB-II upon discharge * | 3009 (53.3) | 70 (52.2) | .869 |

| Lipid lowering drugs upon discharge * | 3388 (60.1) | 41 (30.6) | <.001 |

| Coronary angiopathy during hospital stay * | 2745 (32.0) | 49 (23.6) | .013 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB-II, angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

* Data only available for the 6443 patients included in PRIAMHO II and MASCARA.

The results from the Cox's regression models are shown on Table 7. The risk of dying during the 28-day-6-month period was significantly lower in 2005 than in 1995 (HR: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.24-0.67) after adjusting for confounding factors and severity. Model 4 shows that the HR for 2005 is 0.42 (95% CI: 0.25-0.68) compared with 2000 (there were no data for 1995). Model 5 proves that the protective effect for 2005, compared to that of 2000, stops being significant when adjusting for antiplatelet, BB and lipid lowering drug prescription upon discharge, maintaining the adjustment for other potential confounding factors. Models 3 and 5 also showed that reperfusion therapy significantly reduced mortality. On the other hand, the independent variables that increased mortality were: age, diabetes mellitus, and Killip class III/IV (maximum during hospital stay).

Table 7. Adjusted Hazard Ratio and 95 Confidence Interval of 6-Month Mortality for 28-Day Survivors for Each Period Studied.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Period | |||||

| 1995 | Reference | Reference | Reference | – | – |

| 2000 | 0.92 (0.68-1.25) | 0.97 (0.71-1.31) | 0.97 (0.72-1.32) | Reference | Reference |

| 2005 | 0.40 (0.25-0.63) | 0.42 (0.26-0.67) | 0.4 (0.24-0.67) | 0.42 (0.25-0.68) | 0.71 (0.42-1.21) |

| Adjustment variables | |||||

| Age | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) | 1.07 (1.05-1.08) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) | 1.05(1.03-1.07) |

| Female sex | 0.93 (0.67-1.29) | 0.90 (0.65-1.25) | 0.79 (0.56-1.1) | 0.79 (0.52-1.22) | 0.81 (0.52-1.24) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.57 (1.17-2.12) | 1.54 (1.14-2.07) | 1.42 (1.05-1.92) | 1.39 (0.95-2.05) | 1.35 (0.91-1.99) |

| AHT | 1.43 (1.07-1.92) | 1.42 (1.06-1.9) | 1.36 (1.01-1.83) | 1.35 (0.92-1.99) | 1.39 (0.94-2.05) |

| AMI/revascularization | 1.22 (0.85-1.75) | 1.20 (0.83-1.72) | 0.96 (0.66-1.4) | 1.01 (0.63-1.64) | 0.97 (0.59-1.69) |

| Q-wave heart attack | -- | 0.87 (0.6-1.26) | 0.86 (0.58-1.26) | 0.95 (0.56-1.60) | 0.97 (0.57-1.64) |

| Primary thrombolysis/reperfusion | -- | 0.64 (0.48-0.86) | 0.66 (0.49-0.88) | 0.55 (0.38-0.81) | 0.61 (0.42-0.89) |

| Anterior AMI | -- | -- | 1.23 (0.92-1.64) | 1.35 (0.93-1.96) | 1.34 (0.92-1.95) |

| Maximum Killip class III/IV | -- | -- | 3.59 (2.59-4.99) | 3.58 (2.36-5.42) | 2.64 (1.73-4.03) |

| ASA/clopidogrel upon discharge a | -- | -- | -- | – | 0.47 (0.3-0.74) |

| Beta-blockers upon discharge a | -- | -- | -- | – | 0.35 (0.22-0.55) |

| Lipid lowering drugs upon discharge a | -- | -- | -- | – | 0.54 (0.34-0.86) |

| Model deviance | 3250.8 | 3241.1 | 3188.3 | 1771 | 1722.7 |

| P b | .008 | <.001 | – | <.001 |

AHT: arterial hypertension; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid.

a We are unable to compare this data with 1995 as treatment upon discharge data was not collected in that year.

b Compared with the previous model.

Our analysis shows a reduction in mortality for STEMI patients at 28 days and 6 months, from 1995 to 2005, considering crude mortality and mortality adjusted for confounding factors.

The risk of dying at 28 days in 2005 was 38% less than in 1995, which coincides with the results of other hospital registries.1, 2, 15 This mortality reduction can mainly be explained because compliance improved with the use of GPC, a factor that justified a risk reduction of 22% during 1990-2006 in the American National Registry of Myocardial Infarction.7 This publication included the following variables: acetylsalicylic acid, BB and heparin during the first 24h, and reperfusion during the recommended time period. Our data (Table 5) confirm these results, and further demonstrates the positive effect of early clopidogrel administration16 and ACEI/ARB-II.17, 18 However, after adjusting for these factors and other confounding factors, patients admitted in 2005 showed a significantly lower mortality than those hospitalized in 1995, which suggests that other factors that have not been considered in the study may have taken effect. A similar result was obtained in a European register on acute coronary syndrome, which compared 30-day mortality in 2000 and 2004, an OR: 0.85 (0.73-0.99).19 These findings force us to reconsider the factors to be measured in future registers. It would probably be useful to include ejection fraction, given its prognostic importance for AMI.

The lower mortality observed at 28 days remained at 6 months. Even adjusting for potential confounding factors, the risk reduced by 58% for patients admitted to hospitals in 2005, as compared with 2000. This is due to more acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, BB and lipid lowering drugs being prescribed upon discharge (Table 7). This result was very similar to that recently published by Bosch et al. in a hospital register for AMI patients with follow-up at 2 years.20 This study also confirms the importance of applying GPC, although we have not observed ACEI/ARB-II to have a beneficial effect during the first six months, probably because not enough time has passed to observe whether they are the factor which reduces the risk of dying.21 In fact, in the study cited above20 the protective effect is observed at two years.

Clinical and Treatment CharacteristicsA high percentage of STEMI patients have a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia1, 2 as has occurred in our study. On the other hand, we have not observed an increase in the age of onset.1, 2, 22 The percentage of women remains stable1, 2, 22and the incidence of heart failure and mechanical complications during the acute AMI phase has reduced as shown in other similar studies.1, 19, 23

The greatest differences with other registers seem to lie in patient treatment. In the MASCARA12 study, the reperfusion therapy most used in Spain was thrombolysis (48%), followed by primary angioplasty (24.2%). At that time, angioplasty was frequently used in many countries in our area,1, 15, 18, 19 with percentages from 39% to 72%. The median door-to-balloon time increased 15min between 2000 and 2005, when the general tendency is for it to decrease.15, 19 That is why experiments conducted in Spain are interesting, for example in study from Mingo et al.24 the door-to-needle time was reduced by 30min, because the emergency transport staff was able to diagnose and advise the cardiologist of the patient's conditions. The door-to-needle time reduced in Spain in 1995-2005, although the median in 2005 was 43min, more than the maximum of 30min recommended by the GPC and more than other times published.19 Furthermore, the number of non-revascularized patients in our environment continues being around 30%, as occurs in the GRACE register,1 which is clearly an excessive figure. These data, which confirm those previously reported by García et al,25 prove that organizational measures need to be implemented to improve health care. In this respect, primary angioplasty networks are a safe option in Spain.26

Administering coadjuvant drugs recommended by the GPC has improved in the CICU and upon discharge, although its use is 5%-15% lower than in other countries,22 except for acetylsalicylic acid.

Study LimitationsThe data analyzed are obtained from registers, meaning that we are unable to ensure that the sample is totally representative of Spanish hospitals, as only a small percentage of hospitals have participated. However, since hospitals were selected randomly, this limitation is weakened. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis performed with patients from the hospitals that participated in the three registers (3892 patients) confirms the overall results. However, we are unable to guarantee that we have included all possible mortality-related factors. As such, despite having adjusted for the main determining prognostic variables, we continued to observe lower risk of dying at 28 days in 2005 than in 1995 (Table 5). This could be indicative of the confounding factors that were produced in 2005 and that were not included in the analysis.

We have studied STEMI patients admitted to the CICU, without analyzing patients attended to in other hospital areas, which could be more severe and have different treatment use rates. Furthermore, the study has not considered the patients’ possible drug contraindications.

The oldest registers do not include variables that have proven interesting in later research projects. For example, the PRIAMHO I did not include data on drugs administered upon discharge.

Finally, the way that some of the variables are defined has changed over time: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, AMI, etc., which could explain some of the changes observed. Although this limitation is common in publications of this type, the recent study by Roger et al.22 shows that the advent of troponin in heart attack diagnosis in 2000 has not changed the trend to lower early mortality or 5-year mortality for AMI during the past two decades. As such, mortality analyses continued to have similar results with higher classic markers, with or without increased troponins. Therefore, the new AMI definition does not mean including AMI patients with a better prognosis.

CONCLUSIONSEarly and six-month mortality for STEMI patients admitted to the CICU substantially reduced in Spain between 1995 and 2005. The therapeutic factors related to these results are increasing reperfusion and using more anti-thrombotic drugs, BB, ACEI and lipid lowering drugs in the CICU, and antiplatelet agents, BB and lipid lowering drug upon discharge. All of these therapies are type I recommendations in the GPC. Nonetheless, the factors examined do not completely explain why mortality has reduced in the acute phase.

FUNDINGThe PRIAMHO I and II registers were conducted using funding from the Sección de Cardiopatía Isquémica de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (Department of Ischaemic Heart Disease from the Spanish Society of Cardiology) and the Boehringer Ingelheim group.

The MASCARA study was funded by the RECAVA network, FIS code (PI04/1408, PI04/1583) and an unrestricted grant from Bristol-Myers-Squibb.

This analysis has been conducted with funding from the Red de Investigación Cardiovascular HERACLES (HERACLES Cardiovascular Research Network): Fondos FEDER-Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FEDER Funds-Ministry of Science and Innovation, Carlos III Health Institute) (Red HERACLES RD06/0009), and the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (University and Research Financial Support Agency) (2005SGR00577).

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

Received 16 November 2010

Accepted 3 May 2011

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiologia, Hospital Txagorritxu, C/ José Atxotegi s/n, 01009 Vitoria-Gasteiz, Álava, Spain. aborau@secardiologia.es