The incorporation of the new antiplatelet agents (NAA) prasugrel and ticagrelor into routine clinical practice is irregular and data from the “real world” remain scarce. We aimed to assess the time trend of NAA use and the clinical safety and efficacy of these drugs compared with those of clopidogrel in a contemporary cohort of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

MethodsA multicenter retrospective observational study was conducted in patients with ACS admitted to coronary care units and prospectively included in the ARIAM-Andalusia registry between 2013 and 2015. In-hospital rates of major cardiovascular events and bleeding with NAA vs clopidogrel were analyzed using propensity score matching and multivariate regression models.

ResultsThe study included 2906 patients: 55% received clopidogrel and 45% NAA. A total of 60% had ST-segment elevation ACS. Use of NAA significantly increased throughout the study. Patients receiving clopidogrel were older and were more likely to have comorbidities. Total mortality, ischemic stroke, and stent thrombosis were lower with NAA (2% vs 9%, P < .0001; 0.1% vs 0.5%, P = .025; 0.07% vs 0.5%, P = .025, respectively). There were no differences in the rate of total bleeding (3% vs 4%; P = NS). After propensity score matching, the mortality reduction with NAA persisted (OR, 0.37; 95%CI, 0.13 to 0.60; P < .0001) with no increase in total bleeding (OR, 1.07; 95%CI, 0.18 to 2.37; P = .094).

ConclusionsIn a “real world” setting, NAA are selectively used in younger patients with less comorbidity and are associated with a reduction in major cardiac events, including mortality, without increasing bleeding compared with clopidogrel.

Keywords

Antithrombotic strategies to treat acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with or without ST-segment elevation are based on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 platelet receptor inhibitor (anti-P2Y12).1,2 Current clinical practice guidelines recommend that clopidogrel be replaced with one of the new antiplatelet agents (NAA), prasugrel or ticagrelor, so long as the bleeding risk is not prohibitive, thus requiring a careful benefit-risk analysis.1,2 However, this recommendation is based on clinical trials conducted in populations that differ from those encountered in routine clinical practice.

Postapproval studies are essential for translating clinical trial results into routine clinical practice. However, data on the real-world use of NAA remain scarce,3–13 and very few studies have brought together data on all 3 anti-P2Y12 drugs.9,12 The observational data available reveal a general underuse of NAA and their more frequent prescription to younger patients with fewer comorbidities, and this differing patient profile could account for the observed net clinical benefit of NAA over clopidogrel.3–6,8–12 Against this background, the reduction in short-term mortality with NAA has been disputed,14 and recent studies have left still-unresolved questions.9,12,15

In Spain, although protocols governing NAA use have been proposed,16 there are no recent multicenter registries evaluating real-world clinical events with the 2 NAA (ticagrelor and prasugrel).10,11,17 Despite this, limitations related to patient characteristics and cost concerns have been published with the aim of facilitating incorporation of NAA into routine clinical practice.17

In this study, we aimed to assess the time trend in NAA use and the clinical safety and efficacy of these drugs compared with those of clopidogrel in a contemporary cohort of ACS patients.

METHODSStudy PopulationA retrospective, multicentre, observational study was conducted in patients with an admission diagnosis of ACS and who were receiving aspirin and an anti-P2Y12 drug (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) at the time of hospital discharge or in-hospital death; the patients were prospectively included in the ARIAM-Andalusia registry between 2013 and 2015. The registry characteristics have been described previously.18–21 Briefly, ARIAM-Andalusia is an ongoing electronic repository that compiles data on all ACS patients admitted to coronary care units in hospitals in Andalusia; data include demographic characteristics, clinical variables, analytical results, treatments, procedures, time to reperfusion, major cardiac and cerebrovascular events, and in-hospital bleeding events. For the present study, we selected data from the 4 tertiary referral hospitals with the most registered patients and the least number of missing study variables. The procedures for data compilation and verification in the online repository are quality audited by the Andalusian School of Public Health.18–21

Clinical VariablesAntiplatelet agents were prescribed by the on-duty physician according to standard clinical practice at each center. Myocardial infarction was identified according to the third universal definition. Ischemic stroke was defined as any cerebrovascular incident causing a neurological deficit lasting for longer than 24hours, and the absence of hemorrhage was confirmed with neuroimaging tests. Stent thrombosis was defined according to Academic Research Consortium criteria.22 All clinical events were previously entered on the data acquisition form and were allocated by consensus among the investigators at each center.19–21 The primary efficacy variable was total in-hospital mortality and the secondary efficacy variables were nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke and probable or definite stent thrombosis. The primary safety variable was the total number of bleeding events according to the TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) criteria.23

Statistical AnalysisAll analyses were stratified according to the type of anti-P2Y12 patients were receiving at the time of hospital discharge or in-hospital death: NAA (prasugrel or ticagrelor as a single category) vs clopidogrel. Depending on their distribution, continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range from the 25th to the 75th percentile] and were compared with the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test. Qualitative variables are expressed as number and percentage and were compared by the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test.

To adjust for differences between treatment groups in baseline characteristics and to attenuate possible confounding by covariates, we calculated the propensity scores (PS) for receiving an NAA,24 using a multivariate regression model that included the following variables: age, sex, body mass, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, bleeding history, peripheral vascular ischemia, history of atrial fibrillation and treatment with oral anticoagulants, ST-segment elevation ACS, in-hospital percutaneous or surgical coronary revascularization, year of admission, 3-vessel disease or left main coronary artery disease, treatment with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, heart failure, renal failure, and total ischemia time (from symptom onset to reperfusion). Patients from each treatment group were propensity-score matched with a 1:1 greedy algorithm (caliper width, 0.05) without replacement, and the goodness-of-fit was assumed to be sufficient if the standardized differences were < 10%.24,25 To analyze the robustness of the results, we conducted additional regression analysis by IPTW (inverse probability of treatment weight), both in the full sample and with restriction to exclude extreme propensity scores.26 The contribution of each patient or weighting was calculated in the NAA group as the inverse of the propensity score (1/PS) and in the clopidogrel group as 1/1-PS. This type of analysis ensures that the contribution of covariates introduced to construct the propensity model does not differ between the members of each group. Between-group differences in baseline characteristics in the matched sample were analyzed with the McNemar test (quantitative variables) and the Student t test for paired data (quantitative variables). Between-group differences in clinical events in the matched sample were analyzed with conditional multivariate regression models, and are expressed as odds ratios (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The results were internally validated by sensitivity analysis of mortality and total bleeding events in distinct patient subgroupings: GRACE and CRUSADE risk scores, age ≥ 75 years, type of ACS, and admission year. The discriminatory power of the regression models was determined with the C statistic, and the models were calibrated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Differences were considered significant at a bilateral P value < .05. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 19 (IBM Corporation; Somers, New York, United States) and STATA 13.1 IC (STATA Corp; College Station, Texas, United States).

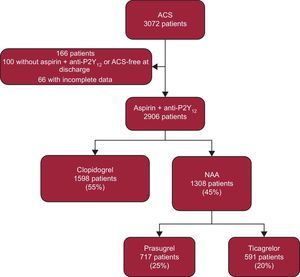

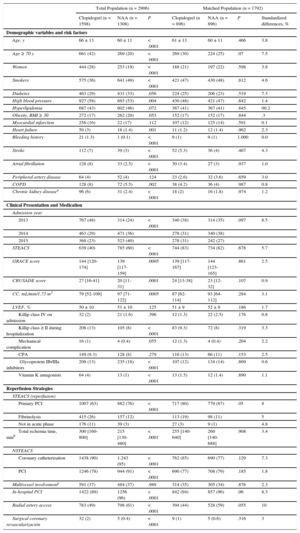

RESULTSA total of 3072 patients were evaluated during the study period, of whom 2096 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Of these patients, 1598 (55%) received clopidogrel and 1308 (45%) received an NAA (717 prasugrel and 591 ticagrelor). Of the patients analyzed, 60% had ST-segment elevation ACS. Overall, the clopidogrel-treated patient group had higher risk scores for ischemic events (GRACE scale) and bleeding (CRUSADE scale); this group also tended to include older patients with more comorbidities and had a higher incidence of in-hospital heart failure, a lower rate of percutaneous coronary intervention, and longer total ischemia times (Table 1). There were no between-group differences in the prevalence of diabetes or previous myocardial infarction, ejection fraction, or the percentages of patients in cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest on admission.

Baseline Characteristics of the Total and Propensity-matched Populations

| Total Population (n = 2906) | Matched Population (n = 1792) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel (n = 1598) | NAA (n = 1308) | P | Clopidogrel (n = 896) | NAA (n = 896) | P | Standardized differences, % | |

| Demographic variables and risk factors | |||||||

| Age, y | 66 ± 13 | 60 ± 11 | < .0001 | 61 ± 13 | 60 ± 11 | .466 | 3.8 |

| Age ≥ 70 y | 661 (42) | 269 (20) | < .0001 | 269 (30) | 224 (25) | .07 | 7.5 |

| Women | 444 (28) | 253 (19) | < .0001 | 188 (21) | 197 (22) | .598 | 3.8 |

| Smokers | 575 (36) | 641 (49) | < .0001 | 421 (47) | 430 (48) | .812 | 4.6 |

| Diabetes | 463 (29) | 431 (33) | .056 | 224 (25) | 206 (23) | .519 | 7.3 |

| High blood pressure | 927 (58) | 693 (53) | .004 | 430 (48) | 421 (47) | .842 | 1.4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 687 (43) | 602 (46) | .072 | 367 (41) | 367 (41) | .845 | 00.2 |

| Obesity, BMI ≥ 30 | 272 (17) | 262 (20) | .053 | 152 (17) | 152 (17) | .844 | .3 |

| Myocardial infarction | 256 (16) | 22 (17) | .112 | 107 (12) | 125 (14) | .591 | 0.1 |

| Heart failure | 50 (3) | 18 (1.4) | .001 | 11 (1.2) | 12 (1.4) | .962 | 2.3 |

| Bleeding history | 21 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | < .0001 | 9 (1) | 9 (1) | 1.000 | 0.0 |

| Stroke | 112 (7) | 39 (3) | < .0001 | 52 (5.3) | 36 (4) | .467 | 4.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 128 (8) | 33 (2.5) | < .0001 | 30 (3.4) | 27 (3) | .937 | 1.0 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 64 (4) | 52 (4) | .124 | 23 (2.6) | 32 (3.6) | .659 | 3.0 |

| COPD | 128 (8) | 72 (5.5) | .002 | 38 (4.2) | 36 (4) | .987 | 0.8 |

| Chronic kidney diseasea | 96 (6) | 31 (2.4) | < .0001 | 18 (2) | 16 (1.8) | .974 | 1.2 |

| Clinical Presentation and Medication | |||||||

| Admission year | |||||||

| 2013 | 767 (48) | 314 (24) | < .0001 | 340 (38) | 314 (35) | .097 | 8.5 |

| 2014 | 463 (29) | 471 (36) | 278 (31) | 340 (38) | |||

| 2015 | 368 (23) | 523 (40) | 278 (31) | 242 (27) | |||

| STEACS | 639 (40) | 785 (60) | < .0001 | 744 (83) | 734 (82) | .678 | 5.7 |

| GRACE score | 144 [120-174] | 139 [117-159] | .0005 | 139 [117-167] | 144 [123-165] | .861 | 2.5 |

| CRUSADE score | 27 [16-41] | 20 [11-31] | .0001 | 24 [13-38] | 23 [12-32] | .107 | 0.9 |

| CC, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 79 [52-109] | 97 [71-122] | .0005 | 87 [62-114] | 93 [64-112] | .284 | 3.1 |

| LVEF, % | 50 ± 10 | 51 ± 10 | .125 | 51 ± 9 | 52 ± 9 | .186 | 1.7 |

| Killip class IV on admission | 32 (2) | 21 (1.6) | .396 | 12 (1.3) | 22 (2.5) | .176 | 0.8 |

| Killip class ≥ II during hospitalization | 208 (13) | 105 (8) | < .0001 | 83 (9.3) | 72 (8) | .319 | 3.3 |

| Mechanical complication | 16 (1) | 4 (0.4) | .055 | 12 (1.3) | 4 (0.4) | .204 | 2.2 |

| CPA | 149 (9.3) | 128 (8) | .279 | 116 (13) | 66 (11) | .153 | 2.5 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 208 (13) | 235 (18) | < .0001 | 107 (12) | 134 (14) | .869 | 0.6 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 64 (4) | 13 (1) | < .0001 | 13 (1.5) | 12 (1.4) | .890 | 1.1 |

| Reperfusion Strategies | |||||||

| STEACS (reperfusion) | |||||||

| Primary PCI | 1007 (63) | 882 (76) | < .0001 | 717 (80) | 779 (87) | .05 | 8 |

| Fibrinolysis | 415 (26) | 157 (12) | 113 (19) | 98 (11) | 5 | ||

| Not in acute phase | 176 (11) | 39 (3) | 27 (3) | 9 (1) | 4.8 | ||

| Total ischemia time, minb | 300 [160-800] | 215 [130-480] | < .0001 | 255 [140-640] | 260 [140-688] | .908 | 3.4 |

| NSTEACS | |||||||

| Coronary catheterization | 1438 (90) | 1.243 (95) | < .0001 | 762 (85) | 690 (77) | .129 | 7.3 |

| PCI | 1246 (78) | 944 (91) | < .0001 | 690 (77) | 708 (79) | .185 | 1.8 |

| Multivessel involvementc | 591 (37) | 484 (37) | .989 | 314 (35) | 305 (34) | .876 | 2.3 |

| In-hospital PCI | 1422 (89) | 1256 (96) | < .0001 | 842 (94) | 857 (96) | .06 | 8.3 |

| Radial artery access | 783 (49) | 798 (61) | < .0001 | 394 (44) | 528 (59) | .055 | 10 |

| Surgical coronary revascularización | 32 (2) | 5 (0.4) | < .0001 | 9 (1) | 5 (0.6) | .316 | 3 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CC, creatine clearance (Cockcroft-Gault); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPA, cardiopulmonary arrest; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEACS, non—ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NAA, new antiplatelet agents; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Data are presented as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range from the 25th to the 75th percentile].

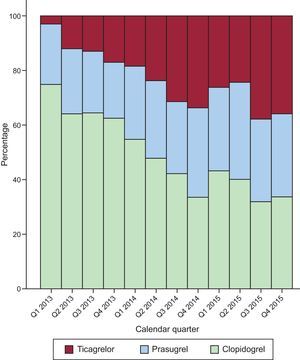

During the course of the study, the rate of NAA use increased significantly (P < .001), from 31% of patients included in 2013, to 53% in 2014, and 63% in 2015; this trend was largely due to an increased use of ticagrelor from 2014 (Figure 2).

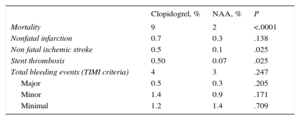

Clinical EventsThe total mortality rate was lower in the NAA-treated group (2% vs 9%; P < .0001) (Table 2). The rate of nonfatal thrombotic events was low, with the NAA group having relatively lower rates of ischemic stroke (0.1% vs 0.5%; P = .025) and stent thrombosis (0.07% vs 0.5%; P = .025); there was no between-group difference in the rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction. There was also no significant difference in mortality between patients taking prasugrel and those taking ticagrelor (1.8% vs 1.4%; P = .701).

Clinical Events by Treatment Group in the Total Study Population

| Clopidogrel, % | NAA, % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 9 | 2 | <.0001 |

| Nonfatal infarction | 0.7 | 0.3 | .138 |

| Non fatal ischemic stroke | 0.5 | 0.1 | .025 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0.50 | 0.07 | .025 |

| Total bleeding events (TIMI criteria) | 4 | 3 | .247 |

| Major | 0.5 | 0.3 | .205 |

| Minor | 1.4 | 0.9 | .171 |

| Minimal | 1.2 | 1.4 | .709 |

NAA, new antiplatelet agents; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Regarding safety, there was no difference in bleeding rate or severity between the 2 treatment groups (Table 2) or in bleeding rate between patients taking prasugrel and those taking ticagrelor (3.1% vs 4.5%; P = .409).

Mortality rates in patient subgroups were similar to the rate in the total population; however, NAA was notably more beneficial in patients at higher ischemic risk (GRACE score > 140: 3% vs 14.5%; P for interaction = .0026) (Figure 3A, ). Moreover, this tendency was maintained after propensity-score matching to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics (). The lower mortality with NAA was evident even for the subgroups at higher bleeding risk (CRUSADE score > 50: 9.4% vs 29%; P =.047), albeit without evidence of interaction (P =.485) (Figure 3A and ). After propensity-score matching, the absolute mortality reduction with NAA was around 12% in the patient subgroup with a high ischemic risk and a high or very high bleeding risk ().

Forest plot of clinical events stratified by patient subgroup. A: Total mortality. B: Total bleeding events. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; NAA, new antiplatelet agents; NSTEACS, non—ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OR, odds ratio; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.

NAA treatment was nonsignificantly associated with a higher overall bleeding rate in all subgroups, especially patients older than 75 years, although there was no evidence of interaction (Figure 3B). This tendency was maintained after propensity-score matching.

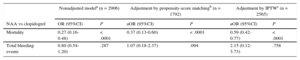

Adjusted AnalysisPropensity scoring matched 896 patients in each treatment group, with a good between-group balance of standardized differences (Table 1). The adjusted multivariate analysis of the propensity-score matched data showed a significant reduction in total mortality with NAA vs clopidogrel (OR, 1.07; 95%CI, 0.18-2.37; P = .094), resulting in a net clinical benefit (Table 3). The IPTW analysis confirmed the lower mortality and the nonsignificant increase in total bleeding events with NAA (Table 3). Both predictive models showed excellent discrimination and calibration. It is noteworthy that, whereas the mortality reduction with NAA was maintained after the 2 adjusted analyses, the reduction in overall bleeding rate with NAA in the total population (OR, 0.80; 95%CI, 0.54-1.20) was reversed to the opposite trend after propensity-score matching. The greater potency of NAA predicts a higher bleeding rate, and this finding therefore reinforces the validity and robustness of the model.

Multivariate Analysis of Safety and Efficacy

| Nonadjusted modela (n = 2906) | Adjustment by propensity-score matchingb (n = 1792) | Adjustment by IPTWc (n = 2565) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA vs clopidogrel | OR (95%CI) | P | aOR (95%CI) | P | aOR (95%CI) | P |

| Mortality | 0.27 (0.16-0.48) | < .0001 | 0.37 (0.13-0.60) | < .0001 | 0.59 (0.42-0.77) | < .0001 |

| Total bleeding events | 0.80 (0.54-1.20) | .287 | 1.07 (0.18-2.37) | .094 | 2.15 (0.12-3.73) | .758 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; anti-P2Y12, P2Y12 platelet receptor inhibitor; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weight; NAA, new antiplatelet agents; OR, odds ratio; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; TIA, transitory ischemic attack.

Covariates included in the regression models: a) mortality: age, sex, diabetes, previous renal failure, previous stroke/TIA, previous myocardial infarction, previous COPD, peripheral artery disease, type of post STEACS reperfusion, total ischemia time, Killip class, cardiac arrest, 3-vessel disease or left main coronary artery disease, and anti-P2Y12 type; b) bleeding: age, sex, bleeding history, CRUSADE score, treatment with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, arterial access route, body mass, history of renal failure, previous stroke/TIA, and anti-P2Y12 type.

The results of this multicenter registry describe current real-world use of NAA and show that these drugs are being progressively incorporated, albeit selectively, into routine clinical practice. This trend translates into a net clinical benefit relative to clopidogrel, characterized by significantly lower in-hospital mortality and no significant increase in the in-hospital bleeding rate. These exploratory results show no differences in mortality reduction and bleeding rates between prasugrel and ticagrelor.

These findings suggest a hopeful tendency toward the use of NAA at the expense of clopidogrel in Spain, in line with guideline recommendations. This is the first study to bring together recent multicenter data on the real-world use of both ticagrelor and prasugrel in Spain. The most recent published data on NAA use come from highly diverse observational studies, and not all of them include both NAA (Table 4).3,4,6–13,27 Similar to the results of other studies,5,7,8,12,13 our data reveal a notable growth in the use of ticagrelor, especially from 2014.

Comparison of Observational Registries Analyzing New Antiplatelet Agents

| Registry | NAA use prevalence, % | Mortality (clopidogrel vs NAA) | Total bleeding events (clopidogrel vs NAA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIRAEUS (2010-2013) | |||

| STEACS10 | 25-27 | — | — |

| NSTEACS11 | 0.7-27.0 | — | — |

| DIOCLES (2012)a | |||

| STEACS10 | 12.0 | — | — |

| NSTEACS11 | 4.3 | — | — |

| U.S. (2011-2013)9 | 27.0 | — | — |

| SWEDEHEART (2010-2013)27,b | 26.5 | HR, 0.83c; 95%CI, 0.75-0.92 | HR, 1.20c; 95%CI, 1.04-1.40 |

| GRAPE (2012-2013)12 | 45.0 | HR, 0.61d; 95%CI, 0.38-0.98 | HR, 1.70e; 95%CI, 1.47-1.97 |

| ARIAM-Andalusia (2013-2015) (current study) | 45.0 | OR, 0.59d; 95%CI, 0.42-0.77 | OR, 2.15e; 95%CI, 0.12-3.73 |

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GRAPE, GReek AntiPlatElet Registry; HR, hazard ratio; IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weight; NAA, new antiplatelet agents; NSTEACS, non—ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OR, odds ratio; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

The increasing use of NAA reported here may have been influenced by the provision for NAA prescription within the infarction protocol for the outpatient management of ST-segment ACS.28 The reasons for the underuse of NAA are varied and go beyond clinical inertia and cost concerns17; one important factor is the likelihood that physicians’ concerns about increased bleeding risk with the stronger antiplatelet agents outweigh consideration of the reduced ischemic risk. In our sample, the potential bleeding risk with NAA was linked to the tendency to prescribe these drugs to patients with a lower risk profile (Table 1). This tendency is also evident from most other real-world registries,3–13 and has become known as the risk-treatment paradox, whereby individuals at higher risk are more likely to receive less aggressive treatments with less clinical benefit.29,30 In the case of anti-P2Y12 drugs, the risk-treatment paradox results in the prescription of clopidogrel to patients with more comorbidity in an attempt to minimize bleeding events. As also reported in other real-world registries, in our population this patient selection could explain the reduction in thrombotic events with NAA (including mortality). However, in line with recent studies,9,12 our adjustment models confirmed a decrease in mortality and ischemic events with NAA vs clopidogrel when more than 20 confounding covariates were taken into consideration (Table 4). The effect of NAA on bleeding rates in adjusted analyses is more varied and may not indicate the superiority of one agent over another9,12; rather, this variability might reflect the differing definitions of bleeding used in each study as well as differences in the baseline characteristics of each treatment group (Table 4). It is therefore important to note that the current study population consisted mainly of ST-segment ACS patients with a low bleeding risk (median CRUSADE score, 23).

Ticagrelor is the latest NAA to be incorporated into clinical practice, and therefore there are few studies to date evaluating the real-world use of this drug.7–9,12,13,27 The results of the SWEDEHEART registry showed a reduction in major cardiac events and an increased bleeding rate with ticagrelor vs clopidogrel, confirming the results of the PLATO trial in real-world patients.27 As in our population, in SWEDEHEART, patients receiving ticagrelor had a lower risk of ischemia and bleeding than the clopidogrel group; however, compared with the NAA group in our study, the SWEDEHEART ticagrelor group had a more favorable risk profile for ischemia (median GRACE score, 99 vs 139) and bleeding (10% vs 13.2% of patients with a high or very high CRUSADE bleeding risk).

In a recent patient subanalysis, Matteau et al.31 examined the balance between ischemic and bleeding risk in clinical trials with drug-eluting stents over a follow-up period of up to 4 years. The analysis showed that ischemic and bleeding risks tend to overlap, but that ischemic risk was nonetheless higher than bleeding risk in 97% of the patients studied. This result is in line with our study, in which 46% of patients had a high ischemic risk (GRACE score > 140), whereas only 17% had a high or very high bleeding risk (CRUSADE score > 40). Recent evidence thus supports the exploratory data presented here, showing a stronger mortality reduction with NAA without increasing severe bleeding events in patients at higher risk of ischemia or even bleeding (). Together, these findings underline the need to individualize treatment assignment to anti-P2Y12 drugs and raise questions about the predictive power of current bleeding risk scales, as well as their usefulness for individualizing antiplatelet treatment in clinical practice, especially among patients with higher comorbidity.32

The present study demonstrates the superior performance and clinical safety of NAA vs clopidogrel in a real-world setting. In line with the major clinical trials, our results confirm NAA therapy as an alternative with a net clinical benefit and underline the need to unify criteria and protocols to help establish these not-so-new antiplatelet agents in routine clinical practice.1,2,16

LimitationsThis study has the usual limitations of registry-based observational studies, and the detected associations should therefore not be interpreted as causal.

The study population consisted of coronary care unit patients, and the study examined only in-hospital events and did not cover the recommended 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy for ACS. Caution should therefore be exercised in extrapolating these results to other populations. The different baseline characteristics and procedures in the 2 treatment groups reflect routine clinical practice; although several types of adjustment were applied, we cannot exclude an influence on the results from confounding covariates not included in the propensity models or not recorded in the study. As with other registries, event allocation was neither centralized nor blind. Nonetheless, events in the ARIAM-Andalusia registry are predefined and subject to periodic external audits, thus ensuring reliable allocation. The results of the subgroup analyses should be regarded as only exploratory. The study recorded treatment allocation at the time of patient discharge or in-hospital death, and therefore the results may have been influenced by antiplatelet switching during hospitalization. However, because of the retrospective nature of the study and the absence of a predefined variable, we were unable to estimate the possible influence of antiplatelet agent switching. This question is being specifically addressed in the ongoing prospective multicenter CREA registry (Spanish acronym for “Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Safety and Efficacy of Switching Antiplatelet”; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02500290).

CONCLUSIONSThe results of this study show that the NAA prasugrel and ticagrelor are increasingly being incorporated into clinical practice, and are being selectively prescribed to patients with a lower risk of ischemia and bleeding. Compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor were both associated with reductions in mortality and major events without significantly increasing the bleeding rate, thus validating the results of major clinical trials to the real world.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

The latest generation antiplatelet agents prasugrel and ticagrelor are recommended above clopidogrel for the treatment of ACS.

- –

Their introduction into routine clinical practice has been irregular.

- –

Data are scarce on the use prevalence of these drugs and on their real-world effectiveness and clinical efficacy.

- –

This study reports a gradual increase in the use of both prasugrel and ticagrelor in routine clinical practice, especially in patients with a lower risk profile.

- –

Compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor were both associated with reductions in mortality and thrombotic events without significantly increasing bleeding events.

- –

Patients at higher ischemic risk showed a higher net clinical benefit with NAA.

- –

The results reinforce guideline recommendations derived from clinical trials and could help with the selection of the appropriate anti-P2Y12 therapy in routine clinical practice.

We thank all local investigators in the ARIAM-Andalusia registry (