Geriatric assessment of elderly individuals with significant aortic stenosis (SAS), also called “severe”, has received growing attention in recent years. Additionally, the prognostic role of frailty has been consolidated in recent months in large-scale studies.

Shimura et al.1 analyzed the prognostic impact of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) in 1215 patients from the Optimized CathEter vAlvular iNtervention (OCEAN-TAVI) registry who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). The CFS is a semiquantitative tool that classifies individuals into 1 of 9 categories, from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill). In this study, 1-year mortality increased progressively with each CFS category.

Little comparative information is available on the different frailty scales. Afilalo et al.2 compared the ability of 7 different frailty scales (Fried criteria, Fried+, CFS, Short Physical Performance Battery, Bern scale, Green test, and the Essential Frailty Toolset [EFT]) to predict 1-year mortality in 1020 patients with SAS who underwent either surgical aortic valve replacement or TAVI. The EFT, which includes time to stand from a seated position, cognitive function (Mini-Mental State Examination), hemoglobin, and serum albumin, showed better predictive value than the other tools analyzed.

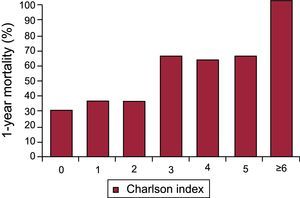

As in octogenarians, good short-term results have been found in nonagenarians who undergo TAVI, although there is controversy about the mid-term prognosis and impact of comorbidity, frailty, and other variables linked to aging on functional outcomes and quality of life. A substudy3 of the PEGASO and IDEAS registries analyzed the impact of comorbidity on treatment and prognosis in nonagenarians with SAS (n = 177). Of the participants, 31.6% had a low degree of comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] < 3). The management was conservative in 84.7%. There was a strong association between the CCI and 1-year mortality, particularly at a CCI ≥ 3 (Figure 1). Nonetheless, the therapeutic strategy was not significantly affected by the degree of comorbidity.

One-year mortality based on degree of comorbidity. Adapted with permission from Bernal et al.3

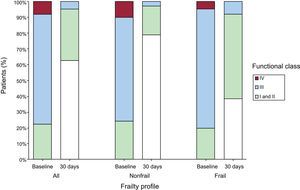

In addition, Okoh et al.4 analyzed the impact of frailty on prognosis and functional outcomes in 75 nonagenarians who underwent TAVI. Frailty was assessed using a score (“frailty score” [FS]) based on grip strength, gait speed, albumin, and activities of daily living. Health status was evaluated at baseline and at 30 days (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire). In total, 30 patients (40%) met the criteria for frailty (FS ≥ 3/4). Frailty was associated with higher 30-day and 2-year mortality. Interestingly, functional status significantly improved only in patients without frailty criteria (Figure 2).

Changes in the functional class after TAVI in the total population and in frail and nonfrail patients. Percentage of patients with each degree of functional class before and after the procedure based on the frailty profile. TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Adapted with permission from Okoh et al.4

Bagiensky et al.5 recently studied the incidence of delirium after a TAVI procedure and its prognostic impact. Of the 141 patients analyzed, 29 had delirium in the first 4 postprocedural days. Development of delirium was associated with transapical access and a higher amount of intraprocedural contrast agent, as well as the presence of frailty. Patients with delirium had higher rates of 30-day and 1-year mortality. This association remained after adjustment for baseline characteristics.

Finally, the role of cardiac rehabilitation in frail elderly patients with SAS has also been investigated. Tarro et al.6 studied 135 patients older than 70 years undergoing surgery or TAVI. The 6-minute walk test was performed, as well as evaluation of functional status (Barthel index), risk of falls (Morse Fall Scale), and comorbidity (CIRS-CI). An intensive rehabilitation program was performed for 3 months. The patients who underwent TAVI had higher degrees of comorbidity, disability, and risk of falls than surgical patients and also tolerated a lower workload and were more likely to require a tailored training program. No complications were associated with the rehabilitation and there was greater functional improvement in both groups after the program, indicating that the rehabilitation program is feasible and safe and can contribute to postprocedural symptomatic improvements in these patients.

Thus, the most recent data clearly strengthen the role of geriatric assessment of elderly individuals with SAS by conclusively helping to identify patients with better postprocedural prognostic, symptomatic, and quality of life outcomes. Optimization of care to elderly patients with SAS and avoiding futile interventions are currently probably the aspects with the greatest room for improvement.

.