There are 3 forms of methamphetamine—speed, base, and ice—differing in their purity (ice is 80% pure, whereas speed is 10%-20% pure). Ice is also called crystal and is known by shabu in the Philippines. It is the free base form of methamphetamine,1 and its most frequent form of consumption is by smoking. Shabu is an emerging drug in Europe with increasing consumption reports, especially in Southeast Asian communities. The 2016 World Drug Report noted an upward trend in the number of seizures of methamphetamine since 2002, reaching a peak of 108 tons in 2014.2

Cardiovascular complications due to cardiac toxicity are the second most common cause of death in methamphetamine abusers; associated cardiovascular pathologies include malignant hypertension, aortic dissection, myocardial infarction, pulmonary hypertension, malignant arrhythmias due to prolonged QT,3 and cardiomyopathy.4,5

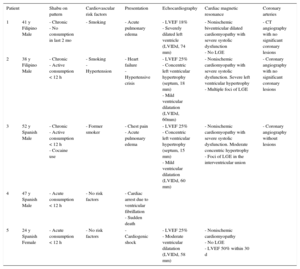

We conducted a prospective study of Shabu consumers who were admitted for cardiac complications in our hospital. From January 2015 to June 2016, 5 patients were identified. Consumption was recognized by anamnesis (2 patients) or positive urinalysis (3 patients). Urinalysis was performed by immunoassay and the results were confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Shabu can be detected within a 60-hour window. In patients without toxicological laboratory confirmation, an evaluation was conducted by the addiction team of our center.

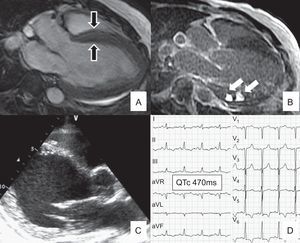

The median patient age was 40.4 ± 10.6 years. Two of the patients were from the Philippines. All 5 patients had elevated serum levels of troponin I (). In addition, 4 of the 5 patients showed QTc interval prolongation (mean QTc, 467 ± 15ms) that normalized before discharge ().

Four patients had severe acute heart failure due to left ventricular dysfunction. Their mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 23.2% ± 3.5%, and their mean left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole was 63.0 ± 7.4mm. All patients were found to have nonischemic cardiomyopathy using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, 2 of the 3 patients with chronic use of Shabu had late gadolinium enhancement with a pattern of multiple foci in lateral and inferior segments (transmural, subepicardial, and subendocardial) in 1 patient and foci in the interventricular septum in the other (Table and Figure).

Cardiac Complications Associated With Consumption of Shabu

| Patient | Shabu on pattern | Cardiovascular risk factors | Presentation | Echocardiography | Cardiac magnetic resonance | Coronary arteries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 y Filipino Male | - Chronic - No consumption in last 2 mo | - Smoking | - Acute pulmonary edema | - LVEF 18% - Severely dilated left ventricle (LVIDd, 74 mm) | - Nonischemic biventricular dilated cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction - No LGE | - CT angiography with no significant coronary lesions |

| 2 | 38 y Filipino Male | - Chronic - Active consumption < 12 h | - Smoking - Hypertension | - Heart failure - Hypertensive crisis | - LVEF 25% - Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (septum, 18 mm) - Mild ventricular dilatation (LVIDd, 60mm) | - Nonischemic cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction. Severe left ventricular hypertrophy - Multiple foci of LGE | - Coronary angiography with no significant coronary lesions |

| 3 | 52 y Spanish Male | - Chronic - Active consumption < 12 h - Cocaine use | - Former smoker | - Chest pain - Acute pulmonary edema | - LVEF 25% - Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (septum, 15 mm) - Mild ventricular dilatation (LVIDd, 60 mm) | - Nonischemic cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction. Moderate concentric hypertrophy - Foci of LGE in the interventricular union | - Coronary angiography without lesions |

| 4 | 47 y Spanish Male | - Acute consumption < 12 h | - No risk factors | - Cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation - Sudden death | |||

| 5 | 24 y Spanish Female | - Acute consumption < 12 h | - No risk factors | - Cardiogenic shock | - LVEF 25% - Moderate ventricular dilatation (LVIDd, 58 mm) | - Nonischemic cardiomyopathy - No LGE - LVEF 50% within 30 d | |

CT, computed tomography; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole.

A and B: Patient number 2 (Table). A: Magnetic resonance imaging showing severe concentric hypertrophy (septum, 18mm; black arrows). B: LGE sequence showing foci of LGE (white arrows) in inferior segments. C: Echocardiographic results for patient number 1 (Table). Severely dilated left ventricle (LVIDd, 74mm). Diastolic sphericity index, 70% (normal, 29% ± 6%). D: Prolonged QTc (470ms) (patient number 2, Table). LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVIDd: left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole; QTc, corrected QT.

In all patients, the most common causes of cardiomyopathy and left ventricular hypertrophy were excluded. Secondary hypertension etiologies were ruled out. Sarcoidosis was excluded in the patient with multiple foci of late gadolinium enhancement. Because 1 patient (number 3; Table) had ST-segment dynamic changes, urgent coronary angiography was performed, which showed no lesions.

Finally, 1 patient without coronary risk factors was admitted for an out of hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. A medicolegal necropsy study was performed. Unfortunately, the results are not available.

Only 2 patients returned for their programmed follow-up visit: 1 patient had no improvement in LVEF at the 1-year follow-up (number 1; Table), whereas the other patient showed a rapid improvement in left ventricular function with a 50% LVEF within the next 30 days (number 5; Table).

By referring to previous reports,3,5 we identified 3 types of cardiomyopathy. Dilated cardiomyopathy was observed in the patient with chronic Shabu consumption and abstinence during the last 2 months. A hypertrophic pattern was seen in 2 men with chronic active consumption. Finally, the woman with acute consumption had a clinical course suggestive of stress cardiomyopathy. Dilated cardiomyopathy could be related to the direct cardiac toxicity of methamphetamine, whereas the mechanism underlying hypertrophic cardiomyopathy could be secondary hypertension due to the activation of peripheral alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors.3,5 Lastly, stress cardiomyopathy has been linked to the acute effects of catecholamines on myocardial adrenoceptors.6 The elevation of troponin levels in all patients supports the mechanism of direct toxicity of methamphetamine on cardiomyocytes because catecholamines can cause myocardial necrosis. Myocardial injury was also evidenced as foci of late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in 2 patients and has been previously described in cocaine abusers. As in our patients, early left ventricular function recovery is reported to be infrequent and related to acute consumption, lesser left ventricular dilation, and the presence of stress cardiomyopathy.6

Given the severity of the observed acute cardiac complications, management should be performed in an acute cardiac care unit with a special focus on electrocardiographic monitoring (QT interval) and echocardiographic follow-up. Hypertension should be aggressively treated. Beta-antagonists should be administered with caution because of the potential risk of unopposed alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction. The administration of alpha-antagonists prior to beta-antagonists or the use of carvedilol/labetalol for their dual alpha and beta antagonism has been recommended.4

In conclusion, cardiac complications related to the consumption of Shabu detected in our center were acute and severe and manifested as pulmonary edema, cardiogenic shock, and sudden death. Because it is an emerging drug, methamphetamine-related cardiac complications might become an important public health problem in Europe. Early recognition of these patients is crucial for adequate initial treatment and complication prevention.