Out-of-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) is one of the leading causes of death in Europe.1 In 1991, the American Heart Association (AHA) proposed a sequence of actions called the chain of survival2 (CS), which included rapid activation of the emergency response system, immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed by bystanders, early defibrillation, and advanced life support performed by professional health workers. The CS has been updated by the AHA3 and the European Resuscitation Council (ERC).1

Although the CS is one of the icons of CRA training and awareness campaigns, in recent years a need has arisen for the creation of complementary actions.1,3,4 Each update has placed increasing emphasis on the importance of the first responder. This person performs activation, which is the most important action of the whole process. However, he or she also performs 50% to 75% (2 or 3 of the 4 parts) or 60% to 80% (3 or 4 of the 5 parts) of the CS links of the ERC1 or the AHA,3 respectively. In 2015, the ERC again highlighted the importance of interaction between the 3 pillars of CRA care1: the coordinating center physician, the lay rescuer, and early access to a defibrillator. The 2015 AHA recommendations also placed emphasis on training rescuers to recognize the unconscious patient and activate the CS (class I recommendation).

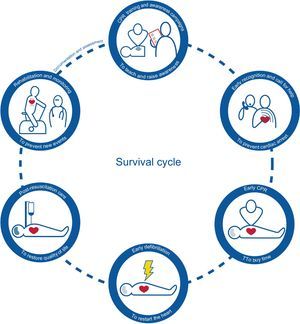

Therefore, a survival cycle (Figure) was proposed1,3,4 that included preparation and rehabilitation. This cycle begins with preparation, which is based on providing the general population with information, strengthening knowledge among those normally in contact with high-risk patients, and facilitating the placement of defibrillators and access to them. Health workers, teachers, politicians, and society in general should include continuous education on CRA in educational centers.5 This decision could promote a true culture of resuscitation within a few years. The rest of the chain would remain the same, apart from the inclusion of rehabilitation as the final link. Rehabilitation would be based on the assessment of the impact of CRA on patients and their families and on their needs. As far as possible, rehabilitation and incorporation mechanisms should be associated with daily life (personal, family, and work).

Finally, the cycle should be closed by creating standardized records that can be used to assess the process and to determine the true magnitude of the problem, the effect of the measures taken, and the impact of improvement actions. Loma-Osorio et al.,6 among others, have demonstrated a high degree of safety and specificity in the use of automated external defibrillators in almost 200 real patients. In that study, half of the patients with a shockable rhythm were successfully treated by an automated external defibrillator. Greater awareness of these issues would help to improve the preparation stage, and therefore promote the survival cycle, by providing more accurate information that would help to identify areas of risk, assess cost-effectiveness, better locate the emergency units, place defibrillators, deploy pedagogical training programs, define the target population to train, and so on.