Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome (SGS) is a connective tissue disorder that must be included in the differential diagnosis of aortic syndromes such as Marfan syndrome (MS) and Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS). SGS is caused by pathogenic variants in the SKI gene, which is involved in the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling pathway.1,2 Fewer than 100 patients have been reported with confirmed SGS. The phenotype includes craniofacial dysmorphism (such as dolichocephaly/scaphocephaly, a prominent forehead, proptosis, hypertelorism, auricular anomalies, and microretrognathia), skeletal, skin, and eye abnormalities, valvular heart diseases, aortic root dilatation, neurological defects, behavioral disorders, and various degrees of cognitive deficit.3–5

We report 2 unrelated patients and discuss our diagnostic and therapeutic approach with special reference to the aortic surgery indication.

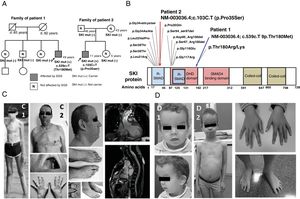

The first patient was diagnosed at 12 years of age with MS based on clinical criteria (systemic score ≥ 7). His parents were not consanguineous and none of his parents or siblings had the same phenotype. At 45 years old, aortic root dilatation (45mm) was detected (figure 1) and its prophylactic surgical replacement was planned, given the suspected MS. The patient was referred to the inherited cardiovascular disease unit for study. A genetic study was performed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) (35 genes, including FBN1), which identified the p.Thr180Met variant in the SKI gene. In addition to the marfanoid habitus, the patient exhibited a characteristic craniofacial dysmorphism, without intellectual disability (table 1). None of his siblings had the variant and, although the parents were not studied, they died at advanced ages. The most likely explanation is that the variant in question is de novo. The patient was diagnosed with SGS and a wait-and-see approach was adopted. After 4 years, no events have occurred and the aortic diameter is stable.

Clinical and genetic study of the probands and their families. A: pedigrees of the families and the genetic study results. B: variants described in the SKI gene at the protein level. C: phenotypes of patient 1 at 12 and 45 years of age (C1 and C2); cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of the patient (aortic root diameter, 45mm). D: phenotypes of patient 2 at 4 and 9 years of age (D1 and D2); photographs taken with prior informed consent. SGS, Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome.

Phenotypes of patients 1 and 2 and of carriers of variants affecting amino acids Thr180 and Pro35

| Patient 1 | Carriers of variants in AA p.Thr180a (n=9)5 | Patient 2 | Carriers of variants in AA p.Pro35b (n=6)2–4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 45 y | Average, 15.8 (range, 2-47) y | 4 y | Average, 17.5 (range, 6-46) y |

| Age at last follow-up | 49 y | Average, 21.8 (range, 3-49) y | 11 y | ND |

| SKI gene variants | c.539C> T, p.Thr180Met | p.Thr180Met (5), p.Thr180Lys (3), p.Thr180Arg (1) | c.103C> T, p.Pro35Ser | p.Pro35Ser (5), p.Pro35Gln (1) |

| Inheritance | Sporadic (without paternal samples) | 7 de novo2 sporadic (without paternal samples) | De novo | 6 de novo |

| Craniosynostosis | Brachycephaly | 0/7, 2 ND | Scaphocephaly | 6/6 |

| Ocular proptosis | Yes | 4/8, 1 ND | Yes | 6/6 |

| Hypertelorism | Yes | 6/8, 1 ND | Yes | 6/6 |

| Visual acuity abnormalities | No | 9 ND | Myopia and astigmatism | 1/6 |

| High-arched palate | Yes | 8/8, 1 ND | Yes | 4/4, 2 ND |

| Ear abnormalities | Large outer ears | 1/7, 2 ND | High-set ears | 1/1, 5 ND |

| Malar hypoplasia | Yes | 5/8, 1 ND | Yes | 6/6 |

| Micrognathia or retrognathia | Yes | 5/9 | Yes | 6/6 |

| Prolapse/mitral valve regurgitation | No | 4/9 | Mitral valve regurgitation | 3/6 |

| Aortic dilatation | Aortic root dilatation (45 mm) | 6/9 | No (24-mm aortic root) | 1/6 |

| Arterial tortuosity | No | 0/4, 5 ND | No | 1/6 (p.Pro35Gln carrier): vertebrobasilar and internal carotid |

| Thoracic deformity | Pectus carinatum | 8/9 | Pectus excavatum | 3/3, 3 ND |

| Arachnodactyly | Yes | 8/9 | Yes | 6/6 |

| Tall stature (for age) | Yes | ND | Yes | ND |

| Dolichostenomelia | Yes | 6/9 | Yes | 6 ND |

| Osteopenia | Yes | 9 ND | No | 6 ND |

| Scoliosis or kyphosis | Severe kyphoscoliosis | 4/8, 1 ND | No | 4/5, 1 ND |

| Joint laxity | Yes | 8/9 | No | 3/3, 3 ND |

| Joint contractures | No | 4/8, 1 ND | Yes, camptodactyly | 5/5, 1 ND |

| Foot deformity | Yes (bilateral corrected) | 9/9 | Yes | 6 ND |

| Acetabular protrusion | No | 4/5, 4 ND | Pelvic tilt due to right femoral dysmetria | 6 ND |

| Flat feet | Yes | 9/9 | No | 6 ND |

| Skin abnormalities | Stretch marks, oily skin with nevus comedonicus | 3/9 | Translucent skin | 3/5 inguinal hernia, 1 ND |

| Venous abnormalities | Varicose veins in the LLs | 9 ND | No | 6 ND |

| Hypotonia | Yes | 2/9 | No | 1/1, 5 ND |

| Other neuromuscular abnormalities | No | 9 ND | Psychomotor retardation | No |

| Brain abnormalities | ND | 9 ND | Dysplasia of the corpus callosum and hippocampus | 6 ND |

| Dural ectasia | No | 9 ND | No | 1/1, 5 ND |

| Cognitive deficit | No | 0/8, 1 ND | Mild | 6/6 |

| Learning problems | No | 3/8, 1 ND | Yes | 6 ND |

| Speech disorder | Yes | 9 ND | Yes | 6 ND |

| Behavioral disorders | ND | 9 ND | ADHD | 6 ND |

| Cancer | No | 9 ND | Hepatoblastoma | 6 ND |

| Other anomalies | No | ND | Right hemibody hypertrophy | ND |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; LLs, lower limbs; ND, not determined.

The p.Thr180Met variant has been reported in 5 sporadic cases of SGS and is classified as pathogenic.5 Two other variants have been described in 4 patients with SGS that affect the same amino acid. In total, 9 affected carriers have been reported; 6 were found to have aortic dilatation at between 15 and 47 years of age: only 1 of these patients was treated with surgery, at 47 years old, after the dilatation reached a diameter of 59mm. The cognitive deficit appears to be mild or absent in these carriers.

The second patient underwent a genetic study at 4 months old due to craniofacial dysmorphism and prenatally diagnosed ventriculomegaly. Umbilical hernia and hemihypertrophy were evident and hepatoblastoma was identified on ultrasound. Beckwith-Wiedemann and otopalatodigital syndromes were ruled out via molecular analysis. When the patient was 4 years old, marfanoid habitus was observed, as well as skeletal anomalies and a learning disorder, and SGS was suspected (figure 1). A genetic study of the SKI gene undertaken using Sanger sequencing identified the p.Pro35Ser variant. The patient is currently 11 years old and does not have aortic dilatation (a 24-mm aortic root).

The p.Pro35Ser variant has been reported to be pathogenic in 5 sporadic cases of SGS. Another variant has been described in 1 patient with SGS (table 1) that affects the same amino acid. In total, 6 affected carriers have been reported at between 6 and 46 years old, and only 1 carrier of another variant (p.Pro35Gln) required surgical intervention at 16 years old due to aortic root dilatation (Z-score=7.01; the aortic diameter was not reported).2–4

SGS displays a complex phenotype requiring its differential diagnosis with MS and LDS. In these syndromes, the surgical indication for aortic dilatation is clearly established. However, there are no clear recommendations for SGS. To date, no SGS patients have been reported to have died from aortic dissection. Close follow-up of the aortic diameter is recommended if risk factors are not present. Prophylactic surgery can be indicated according to some expert recommendations (in the 50-55-mm range or with a rate of progression > 5mm/y6). Given the lack of large studies of this disease due to its very low prevalence, the reporting is required of more clinical cases.

The clinical application of gene panels via NGS to the study of aortic syndromes facilitates the analysis of these overlapping diseases that have been linked to adverse cardiovascular events, which can be less severe or very severe and/or multiple and require more aggressive clinical and surgical approaches.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTL. Monserrat is a shareholder in the genetic company Health in Code. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

We particularly thank the patients and their families for sharing their clinical information and images for this article. We also thank Dr Carme Vila Obradors (of the primary care team of Sant Quirze del Vallès) for her commitment to children with rare diseases.