The present report updates the clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart transplant in Spain to 2018.

MethodsProspective registry of all the heart transplants performed between 1984 and 2018 in Spain. Specifically, temporal trends in clinical characteristics and outcomes are described for the period from 2009 to 2017.

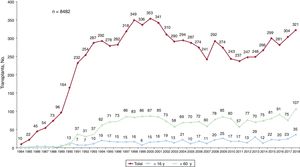

ResultsIn 2018, 321 transplants were performed (8494 since 1984; 2719 between 2009 and 2018). Compared with the previous year, the number of transplants performed in 2018 rose by 52% in recipients younger than 16 years and by 42% in those older than 60 years. In the last decade, significant temporal trends were observed in recipient characteristics (better pretransplant renal function, higher rates of diabetes, more urgent transplants, and greater use of pretrasplant circulatory support, particularly ventricular assist devices), donor characteristics (higher donor age, more female donors, and higher frequencies of cerebrovascular cause of death and predonation cardiac arrest and lower ischemia time). Survival significantly improved in the last decade, mainly due to lower mortality due to primary graft failure.

ConclusionsThe number of heart transplants is increasing in Spain, with a progressive improvement in survival.

Keywords

The RECT (Registro Español de Transplante Cardiaco) annual report highlighting the main characteristics and outcomes of all heart transplants performed in Spain is the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry's main activity. Produced under the principles of disclosure and transparency, this report is an essential tool for guiding clinical and organizational decision-making among the cardiology community involved in the care of advanced heart failure and heart transplant patients. The current report provides an overview of heart transplant activity in Spain in 2018.

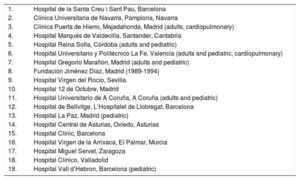

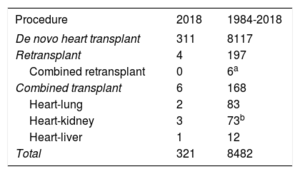

MethodsPatients and ProceduresThe report was produced using the methods described in past editions.1 The number of Spanish hospitals running active heart transplant programs in 2018 remained stable at 18. Of these hospitals, 2 perform pediatric transplants only, 4 perform pediatric and adult transplants, and 2 perform cardiopulmonary transplants (table 1). Between 1984 and 2018, 8494 transplants were performed across Spain (figure 1). The types of transplant performed during this period and in 2018 in particular are summarized in table 2. This report presents data for 2018 and draws comparisons with the period spanning 2009-2018. To detect trends over this decade, data were analyzed by 3-year periods (2009-2011, 2012-2014, and 2015-2017) for all data except percentage of urgent transplants, type of circulatory support used in patients awaiting transplant, and donor age, which were analyzed on a yearly basis.

Hospitals Participating in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry by Order of First Transplant Performed (1984-2018)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid (adults, cardiopulmonary) |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba (adults and pediatric) |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia (adults and pediatric, cardiopulmonary) |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adults and pediatric) |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) |

| 9. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla |

| 10. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña (adults and pediatric) |

| 12. | Hospital de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona |

| 13. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) |

| 14. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia |

| 17. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (pediatric) |

Procedure Type—Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (1984-2018)

| Procedure | 2018 | 1984-2018 |

|---|---|---|

| De novo heart transplant | 311 | 8117 |

| Retransplant | 4 | 197 |

| Combined retransplant | 0 | 6a |

| Combined transplant | 6 | 168 |

| Heart-lung | 2 | 83 |

| Heart-kidney | 3 | 73b |

| Heart-liver | 1 | 12 |

| Total | 321 | 8482 |

Total number of transplants performed in Spain between 1984 and 2018: 8494. Data for 12 cases are missing from the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry.

Continuous and categorical variables are expressed as mean (SD) and percentages, respectively. Between-group differences were analyzed using the Kendall Tau nonparametric test to determine the significance of time series trends for categorical data and by analysis of variance with polynomial contrasts for continuous data. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the logrank test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of less than .05.

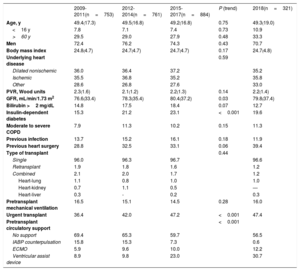

ResultsRecipient CharacteristicsRecipient characteristics are summarized in table 3. A total of 321 transplants were performed in 2018. Compared with 2017, there was a 42% increase in recipients older than 60 years and a 52% increase in those younger than 16 years. Mean (SD) age was 49 (19) years and 70.7% of the recipients were men. The proportion of combined transplants and retransplants remained stable at around 3% of the total. In the 10-year period spanning 2009-2018, there was a significant trend towards improved pretransplant renal function (P=.03) and an increased proportion of recipients with diabetes (P<.001). A nonsignificant trend was observed for increased pretransplant bilirubin levels (P=.07) and more heart surgery procedures among those waiting for a transplant (P=.06).

Recipient Characteristics—Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2009-2018)

| 2009-2011(n=753) | 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | P (trend) | 2018(n=321) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49.4(17.3) | 49.5(16.8) | 49.2(16.8) | 0.75 | 49.3(19.0) |

| <16 y | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 0.73 | 10.9 |

| >60 y | 29.5 | 29.0 | 27.9 | 0.48 | 33.3 |

| Men | 72.4 | 76.2 | 74.3 | 0.43 | 70.7 |

| Body mass index | 24.8(4.7) | 24.7(4.7) | 24.7(4.7) | 0.17 | 24.7(4.8) |

| Underlying heart disease | 0.59 | ||||

| Dilated nonischemic | 36.0 | 36.4 | 37.2 | 35.2 | |

| Ischemic | 35.5 | 36.8 | 35.2 | 35.8 | |

| Other | 28.6 | 26.8 | 27.6 | 33.0 | |

| PVR, Wood units | 2.3(1.6) | 2.1(1.2) | 2.2(1.3) | 0.14 | 2.2(1.4) |

| GFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 76.6(33.4) | 78.3(35.4) | 80.4(37.2) | 0.03 | 79.8(37.4) |

| Bilirubin >2 mg/dL | 14.8 | 17.5 | 18.4 | 0.07 | 12.7 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 15.3 | 21.2 | 23.1 | <0.001 | 19.6 |

| Moderate to severe COPD | 7.9 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 0.15 | 11.3 |

| Previous infection | 13.7 | 15.2 | 16.1 | 0.18 | 11.9 |

| Previous heart surgery | 28.8 | 32.5 | 33.1 | 0.06 | 39.4 |

| Type of transplant | 0.44 | ||||

| Single | 96.0 | 96.3 | 96.7 | 96.6 | |

| Retransplant | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.2 | |

| Combined | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 | |

| Heart-lung | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Heart-kidney | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | — | |

| Heart-liver | 0.3 | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 16.5 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 0.28 | 16.0 |

| Urgent transplant | 36.4 | 42.0 | 47.2 | <0.001 | 47.4 |

| Pretransplant circulatory support | <0.001 | ||||

| No support | 69.4 | 65.3 | 59.7 | 56.5 | |

| IABP counterpulsation | 15.8 | 15.3 | 7.3 | 0.6 | |

| ECMO | 5.9 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 12.2 | |

| Ventricular assist device | 8.9 | 9.8 | 23.0 | 30.7 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Data are expressed as percentages or mean (SD).

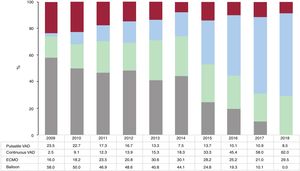

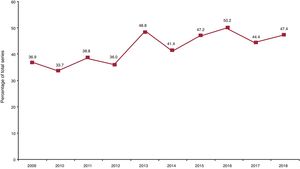

Pretransplant circulatory support was required in 43.5% of recipients. Intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation (IABP) practically disappeared as a means of circulatory support in 2018, and there was an increase in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and ventricular assist devices (VADs) (figure 2). Most of the VADs were continuous-flow devices. Almost half the transplants performed in 2018 were urgent (47.4%), maintaining the trend observed for 2009-2018 (figure 3).

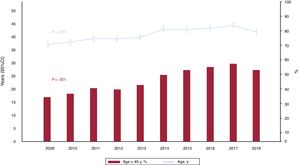

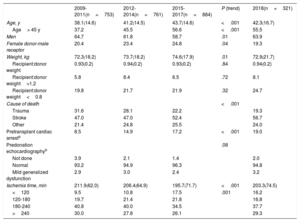

Donor characteristics are summarized in table 4. While donors were slightly younger in 2018 compared with 2017, the trend towards a higher donor age in the past decade remained highly significant. Over 50% of donors in 2018 were older than 45 years (figure 4). The trend towards an increasing proportion of donors who died of stroke and a decrease in those who died of trauma remained highly significant, as did the increase in donors with pretransplant cardiac arrest (P<.001). There was also an increase in cold ischemia time from 2017 to 2018, mainly attributable to more transplants with an ischemia time of over 3hours and fewer transplants with an ischemia time of under 2hours.

Donor Characteristics and Ischemia Time—Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2009-2018)

| 2009-2011(n=753) | 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | P (trend) | 2018(n=321) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 38.1(14.6) | 41.2(14.5) | 43.7(14.6) | <.001 | 42.3(16.7) |

| Age> 45 y | 37.2 | 45.5 | 56.6 | <.001 | 55.5 |

| Men | 64.7 | 61.8 | 58.7 | .01 | 63.9 |

| Female donor-male receptor | 20.4 | 23.4 | 24.8 | .04 | 19.3 |

| Weight, kg | 72.3(18.2) | 73.7(18.2) | 74.6(17.9) | .01 | 72.9(21.7) |

| Recipient:donor weight | 0.93(0.2) | 0.94(0.2) | 0.93(0.2) | .84 | 0.94(0.2) |

| Recipient:donor weight>1.2 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 6.5 | .72 | 8.1 |

| Recipient:donor weight<0.8 | 19.8 | 21.7 | 21.9 | .32 | 24.7 |

| Cause of death | <.001 | ||||

| Trauma | 31.6 | 28.1 | 22.2 | 19.3 | |

| Stroke | 47.0 | 47.0 | 52.4 | 56.7 | |

| Other | 21.4 | 24.8 | 25.5 | 24.0 | |

| Pretransplant cardiac arresta | 8.5 | 14.9 | 17.2 | <.001 | 19.0 |

| Predonation echocardiographyb | .08 | ||||

| Not done | 3.9 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.0 | |

| Normal | 93.2 | 94.9 | 96.3 | 94.8 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.2 | |

| Ischemia time, min | 211.9(62.0) | 206.4(64.9) | 195.7(71.7) | <.001 | 203.3(74.5) |

| <120 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 17.5 | .001 | 16.2 |

| 120-180 | 19.7 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 16.8 | |

| 180-240 | 40.8 | 40.0 | 34.5 | 37.7 | |

| >240 | 30.0 | 27.8 | 26.1 | 29.3 |

Data are presented as percentages or mean (SD).

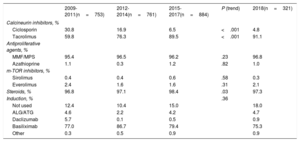

The drugs used for induction immunosuppression are summarized in table 5. The main ones used in 2018 are similar to those from the preceding 10 years and included tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids. The proportion of patients who received antibody-based induction therapy (mainly with basiliximab) was also similar.

Induction Immunosuppression —Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2009-2018)

| 2009-2011(n=753) | 2012-2014(n=761) | 2015-2017(n=884) | P (trend) | 2018(n=321) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin inhibitors, % | |||||

| Ciclosporin | 30.8 | 16.9 | 6.5 | <.001 | 4.8 |

| Tacrolimus | 59.8 | 76.3 | 89.5 | <.001 | 91.1 |

| Antiproliferative agents, % | |||||

| MMF/MPS | 95.4 | 96.5 | 96.2 | .23 | 96.8 |

| Azathioprine | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.2 | .82 | 1.0 |

| m-TOR inhibitors, % | |||||

| Sirolimus | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | .58 | 0.3 |

| Everolimus | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | .31 | 2.1 |

| Steroids, % | 96.8 | 97.1 | 98.4 | .03 | 97.3 |

| Induction, % | .36 | ||||

| Not used | 12.4 | 10.4 | 15.0 | 18.0 | |

| ALG/ATG | 4.6 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 4.7 | |

| Daclizumab | 5.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| Basiliximab | 77.0 | 86.7 | 79.4 | 75.3 | |

| Other | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; ATG, antithymocyte globulin, MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPS, mycophenolate sodium.

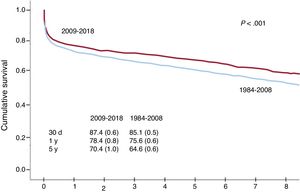

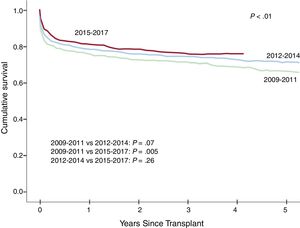

Survival rates were significantly higher in 2009-2018 than in 1984-2008 (figure 5). Both early survival (first year after transplant) and medium-term survival (first 5 years after transplant) improved. Overall, survival improved progressively over the decade, with a significant difference (P=.005) observed for outcomes between 2015-2017 and 2009-2011 (figure 6).

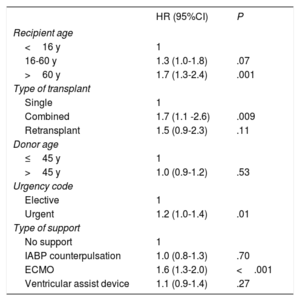

The factors influencing survival in 2009-2018 (table 6) were very similar to those identified in the previous decade.2 Donor age, at least during the period contemplated, did not have any prognostic significance. A recipient age of over 60 years, by contrast, had a significantly greater influence on survival than one of under 16 years (P=.001). Combined transplants were associated with significantly worse survival than single transplants, primarily due to poorer cardiopulmonary transplant outcomes. Finally, patients who underwent an urgent transplant had a 20% increased likelihood of dying than those who underwent an elective transplant. This higher risk is attributable to transplant outcomes in patients supported by pretransplant ECMO, who had a 70% higher risk of death compared with those who underwent elective transplant.

Univariate Survival Analysis of Baseline Recipient, Donor, and Procedure Characteristics (2009-2018)

| HR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | ||

| <16 y | 1 | |

| 16-60 y | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | .07 |

| >60 y | 1.7 (1.3-2.4) | .001 |

| Type of transplant | ||

| Single | 1 | |

| Combined | 1.7 (1.1 -2.6) | .009 |

| Retransplant | 1.5 (0.9-2.3) | .11 |

| Donor age | ||

| ≤45 y | 1 | |

| >45 y | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | .53 |

| Urgency code | ||

| Elective | 1 | |

| Urgent | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .01 |

| Type of support | ||

| No support | 1 | |

| IABP counterpulsation | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | .70 |

| ECMO | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) | <.001 |

| Ventricular assist device | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | .27 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR, hazard ratio.

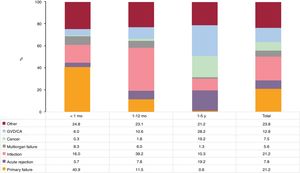

The main causes of death in the first 5 years following transplant were primary graft failure, infection, and graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest (figure 7). The main cause of death in the first month was primary graft failure, which was responsible for 40.9% of all deaths. The other main causes of death were infection between months 2 and 12 (39.2%) and graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest between years 1 and 5 (28.2%). Acute rejection was responsible for 7.8% of all deaths, and together with cancer, it was the second most common cause of death between 1 and 5 years posttransplant (19.2% in both cases).

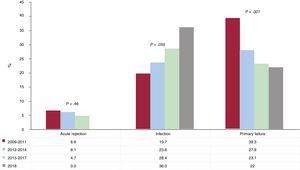

Trends in causes of death in year 1 were analyzed, as most patients survived this period (figure 8). The importance of primary graft failure as a cause of death in the first year after transplant decreased very significantly over the decade analyzed (P=.001): it caused 39.3% of deaths in 2009-2011 versus 23.1% of deaths in 2015-2017, and the downward trend continued in 2018 (22.0%). By contrast, there was a nonsignificant trend towards an increase in the importance of infection as a cause of death in the first year posttransplant over the 10 years analyzed. In this case, infection caused 19.7% of deaths in 2009-2011, 28.4% in 2015-2017, and 36.0% in 2018. Acute rejection as a cause of death remained stable over the decade and caused no deaths in 2018.

DISCUSSIONThe most significant findings of the RECT's report for transplant activity in Spain in 2018 is that a) heart transplants are increasing and b) survival rates are continuing to improve. The number of transplants in 2018 confirms the upward trend observed annually since the low of 2011. The increase in 2018 was due to an increase in procedures in the youngest and oldest age groups (<16 and >60 years). Pediatric transplants also grew in number, probably because transplant programs launched in later years have reached a certain level of maturity and because ABO-incompatible transplantation is now possible. There was also a notable increase in the use of grafts that until recent years were considered less than ideal, as evidenced by the progressive increase in donor age over the past decade and the increasing proportion of donors with cardiac arrest.

Survival rates have continued to improve over the years, with statistical differences detected between 3-year stretches, despite the relatively short overall period analyzed. Both short-term and medium-term survival have improved. The reduction in early mortality is very likely due to successful management of primary graft failure (whose importance as the main cause of death in year 1 posttransplant decreased very significantly over the 10 years analyzed) and acute rejection (which has practically disappeared as a cause of death). The use of increasingly short ischemia times may also have contributed to improved survival.

The use of pretransplant circulatory support devices became widespread in 2009, and one of the main changes observed in recipient characteristics is the increased use of this form of support as a bridge to transplant. As a result of changes to urgency status criteria in June 2017, IABPs were used very little in 2018 and ECMO use leveled off. The use of VADS, by contrast, increased, confirming the tendency observed for the preceding 3-year period. The significant trend detected for improved pretransplant renal function appear to support the benefits of VADs for maintaining adequate clinical stability in patients awaiting a transplant, as do the results of another analysis of RECT data showing improvements in tissue perfusion.3 Finally, temporary circulatory support has proven efficacy for the treatment of primary graft failure4 and its increasing use probably explains the decrease in deaths due to this cause in our series.

CONCLUSIONSThe results observed for heart transplant activity in Spain for 2018 confirm the previously observed trends towards an increase in transplant procedures and a progressive improvement in survival outcomes.

Conflicts of InterestNone declared.

| Hospital | Collaborators |

|---|---|

| Clínica Universitaria Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid | Manuel Gómez-Bueno, Francisco Hernández-Pérez |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia | Soledad Martínez-Penades, Mónica Cebrián-Pinar, Raquel López-Vilella, Ignacio Sánchez-Lázaro, Luis Martínez-Dolz |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña | María J. Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Amador López-Granados, Carmen Segura-Saintgerons, Dolores Mesa, Martín Ruiz, Elías Romo, Francisco Carrasco, Jose López-Aguilera |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander | Manuel Cobo, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, Jose A. Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal-Herrera |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón (adults), Madrid | Manuel Martínez-Sellés, Carlos Ortiz, Eduardo Zataraín, María Jesús Valero, Juan Fernández-Yáñez, Paula Navas, Javier Castrodeza |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | M. Dolores García-Cosío, Laura Morán-Fernández, Zorba Blázquez, Pedro Caravaca |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Eulàlia Roig-Minguell, Vicens Brossa-Loidi, Sonia Mirabet-Pérez, Laura López-López |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | Diego Rangel-Sousa |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Nicolás Manito-Lorite, Carles Díez-López, Josep Roca-Elías |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona | Gregorio Rábago-Aracil |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | María Ángeles Castel, Marta Farrero, Ana García-Álvarez |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo | José Luis Lambert-Rodríguez, Beatriz Díaz-Molina, María José Bernardo-Rodríguez |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón (pediatric), Madrid | Manuela Camino-López, Juan Miguel Gil-Jaurena, Nuria Gil-Villanueva |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia | Iris Garrido-Bravo, Domingo A. Pascual-Figal, Francisco J. Pastor-Pérez |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Pórtoles-Ocampo, Marisa Sanz-Julvé |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de La Fuente-Galán, Javier Tobar-Ruiz, Ana María Correa-Fernández |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Luis García-Guereta-Silva, Álvaro González-Rocafort, Carlos Labradero de Lera, Luz Polo-López |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Dimpna C. Albert-Brotons, Ferrán Gran-Ipiña, Raúl Abella-Antón |