The present report describes the clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart transplants in Spain and updates the data to 2019.

MethodsWe describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart transplants performed in Spain in 2019, as well as trends in this procedure from 2010 to 2018.

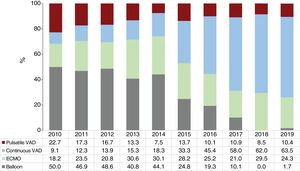

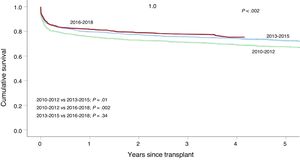

ResultsIn 2019, 300 transplants were performed (8794 since 1984; 2745 between 2010 and 2019). Compared with previous years, the most notable findings were the decreasing rate of urgent transplants (38%), and the consolidation of the type of circulatory support prior to transplant, with an almost complete disappearance of counterpulsation balloon (0.7%), stabilization in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (9.6%), and an increase in the use of ventricular assist devices (29.0%). Survival from 2016 to 2018 was similar to that from 2013 to 2015 (P=.34). Survival in both these periods was better than that from 2010 to 2012 (P=.002 and P=.01, respectively).

ConclusionsHeart transplant activity has remained stable during the last few years, as have outcomes (in terms of survival). There has been a trend to a lower rate of urgent transplants and to a higher use of ventricular assist devices prior to transplant.

Keywords

In 2019, the heart transplant field celebrated its 35th anniversary in Spain. The Spanish Heart Transplant Registry was formed at the end of 1989 and published its first activity report in Revista Española de Cardiología in 1991.1 Produced under the principles of accountability and transparency, these documents have annually reported the activity and outcomes of all heart transplants carried out in Spain since the first such procedure was performed in 1984. Over time, the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry has become an essential tool for reporting the latest aspects of clinical practice in our country, as well as a clinical research platform.2

The present report provides an update on the activity and outcomes of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry until December 31, 2019, with a special focus on the last 10 years.

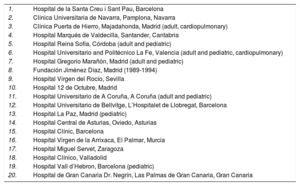

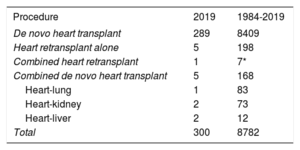

METHODSPatients and proceduresA summary has already been published of the main methods used in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry.3 In 2019, an adult heart transplant program was started in Dr Negrin University Hospital of Gran Canaria, bringing the total number of active centers to 19. There have been no changes from previous years in the structure of the activity of the distinct hospitals (eg, pediatric transplant, multiorgan transplant)4,5 (table 1). From 1984 to 2019, 8794 transplants were performed (figure 1); the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry has complete follow-up information on 8782 of these transplants, which form the basis of the current analysis. The types of transplants performed in 2019 and in the entire series are summarized in table 2. This report provides the relevant data for 2019 and compares them with those of the last 10 years (2010-2019). The changes over time for the period under study were analyzed in 3-year periods (2010-2012, 2013-2015, and 2016-2018), except for the percentage of urgent transplants, the types of pretransplant circulatory support, and donor age, which were analyzed by year.

Hospitals participating in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry from 1984-2019 (in order of first transplant performed)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra |

| 3. | Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid (adult, cardiopulmonary) |

| 4. | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba (adult and pediatric) |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario and Politécnico La Fe, Valencia (adult and pediatric, cardiopulmonary) |

| 7. | Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (adult and pediatric) |

| 8. | Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) |

| 9. | Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla |

| 10. | Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña (adult and pediatric) |

| 12. | Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona |

| 13. | Hospital La Paz, Madrid (pediatric) |

| 14. | Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia |

| 17. | Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (pediatric) |

| 20. | Hospital de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria |

Procedure type in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (1984-2019)

| Procedure | 2019 | 1984-2019 |

|---|---|---|

| De novo heart transplant | 289 | 8409 |

| Heart retransplant alone | 5 | 198 |

| Combined heart retransplant | 1 | 7* |

| Combined de novo heart transplant | 5 | 168 |

| Heart-lung | 1 | 83 |

| Heart-kidney | 2 | 73 |

| Heart-liver | 2 | 12 |

| Total | 300 | 8782 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Differences among time periods were analyzed using a nonparametric test for time series data (Kendall τ) for categorical variables and ANOVA (analysis of variance) with polynomial fit for continuous variables. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier test and were compared using a log-rank test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

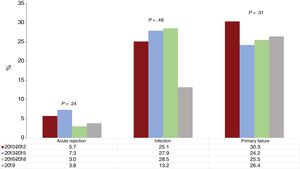

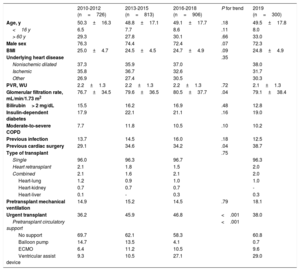

RESULTSRecipient characteristicsRecipient characteristics are summarized in table 3. A total of 300 transplants were performed in 2019. Compared with 2018, the decrease in the number of procedures was mainly due to fewer pediatric patients (younger than 16 years old). The mean recipient age was 49.5 ± 17.8 years, with no significant changes in the last 10 years. Overall, 72.3% were men, confirming the trend in the last decade for an increase, albeit nonsignificant, in transplants in women. The percentages of multiorgan transplants and retransplants were stable, at about 2% overall. In the last 10 years, the only significant trends were the improvement in renal function at transplant and the increase in pretransplant cardiac surgery (both P = .04). The latter variable was correlated with increased use of ventricular assist devices in 2019, with a tendency for a slight decrease in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (figure 2). There was a major decrease in urgent procedures in 2019 (38.0%) vs the tendency of previous years (46.8% in 2016-2018) (figure 3).

Recipient characteristics in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2010-2019)

| 2010-2012 (n=726) | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | P for trend | 2019 (n=300) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 50.3±16.3 | 48.8±17.1 | 49.1±17.7 | .18 | 49.5±17.8 |

| <16 y | 6.5 | 7.7 | 8.6 | .11 | 8.0 |

| > 60 y | 29.3 | 27.8 | 30.1 | .66 | 33.0 |

| Male sex | 76.3 | 74.4 | 72.4 | .07 | 72.3 |

| BMI | 25.0±4.7 | 24.5±4.5 | 24.7±4.9 | .09 | 24.8±4.9 |

| Underlying heart disease | .35 | ||||

| Nonischemic dilated | 37.3 | 35.9 | 37.0 | 38.0 | |

| Ischemic | 35.8 | 36.7 | 32.6 | 31.7 | |

| Other | 26.9 | 27.4 | 30.5 | 30.3 | |

| PVR, WU | 2.2±1.3 | 2.2±1.3 | 2.2±1.3 | .72 | 2.1±1.3 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 76.7±34.5 | 79.6±36.5 | 80.5±37.7 | .04 | 79.1±38.4 |

| Bilirubin> 2 mg/dL | 15.5 | 16.2 | 16.9 | .48 | 12.8 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 17.9 | 22.1 | 21.1 | .16 | 19.0 |

| Moderate-to-severe COPD | 7.7 | 11.8 | 10.5 | .10 | 10.2 |

| Previous infection | 13.7 | 14.5 | 16.0 | .18 | 12.5 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 29.1 | 34.6 | 34.2 | .04 | 38.7 |

| Type of transplant | .75 | ||||

| Single | 96.0 | 96.3 | 96.7 | 96.3 | |

| Heart retransplant | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Combined | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| Heart-lung | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Heart-kidney | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | - | |

| Heart-liver | 0.1 | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 14.9 | 15.2 | 14.5 | .79 | 18.1 |

| Urgent transplant | 36.2 | 45.9 | 46.8 | <.001 | 38.0 |

| Pretransplant circulatory support | <.001 | ||||

| No support | 69.7 | 62.1 | 58.3 | 60.8 | |

| Balloon pump | 14.7 | 13.5 | 4.1 | 0.7 | |

| ECMO | 6.4 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 9.6 | |

| Ventricular assist device | 9.3 | 10.5 | 27.1 | 29.0 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Values are expressed as percentage or mean ± standard deviation.

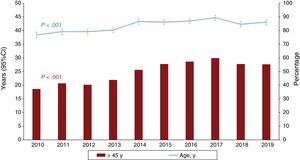

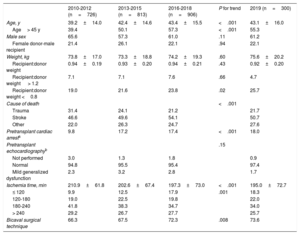

Donor characteristics are summarized in table 4. Donor age was stable vs the previous 3-year period, although the tendency for an increase in the last 10 years was highly significant. In 2019, 55% of donors were older than 45 years of age (figure 4). There was a slight decrease in the number of donors who died of stroke, with a corresponding increase in those who died of other causes. There was another small but consistent increase in the number of donors with pretransplant cardiac arrest (18% in 2019), although there was also a decrease in donors with mild dysfunction on pretransplant echocardiography. The cold ischemia time fell again, a tendency seen in the last 10 years, with an average time in 2019 of a little more than 3hours In addition, almost 3 of every 4 transplants were performed with a bicaval technique, a trend that now appears established.

Donor characteristics and procedure times in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2010-2019)

| 2010-2012 (n=726) | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | P for trend | 2019 (n=300) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 39.2±14.0 | 42.4±14.6 | 43.4±15.5 | <.001 | 43.1±16.0 |

| Age> 45 y | 39.4 | 50.1 | 57.3 | <.001 | 55.3 |

| Male sex | 65.6 | 57.3 | 61.0 | .11 | 61.2 |

| Female donor-male recipient | 21.4 | 26.1 | 22.1 | .94 | 22.1 |

| Weight, kg | 73.8±17.0 | 73.3±18.8 | 74.2±19.3 | .60 | 75.6±20.2 |

| Recipient:donor weight | 0.94±0.19 | 0.93±0.20 | 0.94±0.21 | .43 | 0.92±0.20 |

| Recipient:donor weight > 1.2 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.6 | .66 | 4.7 |

| Recipient:donor weight <0.8 | 19.0 | 21.6 | 23.8 | .02 | 25.7 |

| Cause of death | <.001 | ||||

| Trauma | 31.4 | 24.1 | 21.2 | 21.7 | |

| Stroke | 46.6 | 49.6 | 54.1 | 50.7 | |

| Other | 22.0 | 26.3 | 24.7 | 27.6 | |

| Pretransplant cardiac arresta | 9.8 | 17.2 | 17.4 | <.001 | 18.0 |

| Pretransplant echocardiographyb | .15 | ||||

| Not performed | 3.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.9 | |

| Normal | 94.8 | 95.5 | 95.4 | 97.4 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 2.3 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 1.7 | |

| Ischemia time, min | 210.9±61.8 | 202.6±67.4 | 197.3±73.0 | <.001 | 195.0±72.7 |

| ≤ 120 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 17.9 | .001 | 18.3 |

| 120-180 | 19.0 | 22.5 | 19.8 | 22.0 | |

| 180-240 | 41.8 | 38.3 | 34.7 | 34.0 | |

| > 240 | 29.2 | 26.7 | 27.7 | 25.7 | |

| Bicaval surgical technique | 66.3 | 67.5 | 72.3 | .008 | 73.6 |

Values are expressed as percentage or mean ± standard deviation.

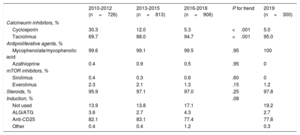

Induction immunosuppression strategies are summarized in table 5. In 2019, the tendencies seen in the last decade were confirmed, with the almost exclusive use of triple therapy comprising tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids. Likewise, more than 80% of patients received antibody-based induction therapy, mainly basiliximab.

Induction immunosuppression in the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry (2010-2019)

| 2010-2012 (n=726) | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | P for trend | 2019 (n=300) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin inhibitors, % | |||||

| Cyclosporin | 30.3 | 12.0 | 5.3 | <.001 | 5.0 |

| Tacrolimus | 69.7 | 88.0 | 94.7 | <.001 | 95.0 |

| Antiproliferative agents, % | |||||

| Mycophenolate/mycophenolic acid | 99.6 | 99.1 | 99.5 | .95 | 100 |

| Azathioprine | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | .95 | 0 |

| mTOR inhibitors, % | |||||

| Sirolimus | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | .60 | 0 |

| Everolimus | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | .15 | 1.2 |

| Steroids, % | 95.9 | 97.1 | 97.0 | .25 | 97.8 |

| Induction, % | .08 | ||||

| Not used | 13.9 | 13.8 | 17.1 | 19.2 | |

| ALG/ATG | 3.6 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 2.7 | |

| Anti-CD25 | 82.1 | 83.1 | 77.4 | 77.8 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; anti-CD25, basiliximab or daclizumab; ATG, antithymocyte globulin.

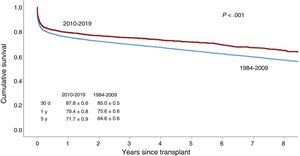

Survival was significantly better from 2010 to 2019 than from 1984 to 2009 (figure 5). This improvement was evident in both early survival (first posttransplant year) and mid-term survival (until the fifth posttransplant year). The final 3-year period (2016-2018) showed a significant improvement in survival vs the 2010 to 2012 period, although survival was similar to that of the immediately preceding period (2013-2015) (figure 6).

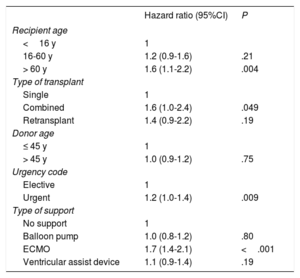

Factors related to survival from 2010 to 2019 (table 6) were maintained at similar levels to those of previous reports.3 The most notable result was that recipient age was associated with survival, unlike donor age. Recipient age > 60 years exerted a highly significantly effect on survival vs age < 16 years (P = .004). As in previous analyses, combined transplant and urgent transplant, due to the effect of pretransplant extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, continued to be associated with worse survival vs heart transplant alone and elective transplant, respectively.

Univariable survival analysis by baseline recipient, donor, and procedure characteristics (2010-2019)

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | ||

| <16 y | 1 | |

| 16-60 y | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | .21 |

| > 60 y | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | .004 |

| Type of transplant | ||

| Single | 1 | |

| Combined | 1.6 (1.0-2.4) | .049 |

| Retransplant | 1.4 (0.9-2.2) | .19 |

| Donor age | ||

| ≤ 45 y | 1 | |

| > 45 y | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | .75 |

| Urgency code | ||

| Elective | 1 | |

| Urgent | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .009 |

| Type of support | ||

| No support | 1 | |

| Balloon pump | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | .80 |

| ECMO | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | <.001 |

| Ventricular assist device | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | .19 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

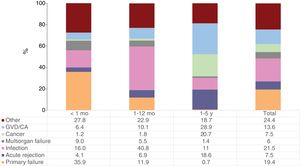

Infection, primary graft failure, and graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest were the most frequent causes of death in the first 5 posttransplant years during the last decade (figure 7). As expected, death from primary graft failure was concentrated in the first posttransplant month, causing a third of deaths. The leading cause of death in the period between the first month and first posttransplant year was infection (40.8% of cases), but was graft vascular disease/cardiac arrest between the first and fifth years (28.9%). These proportions mirror those observed in previous reports, as do the high incidence of death due to acute rejection observed between the first and fifth posttransplant years (18.6%) and that due to cancer in the same period.

Mortality in the first year due to primary graft failure and acute rejection stabilized in 2019. In contrast, 2019 showed a reduction of almost one-half in patients who died of infection in this early period (figure 8).

DISCUSSIONThe main findings of the present updated analysis of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry are as follows: a) confirmation of the trends detected in the last decade regarding the main recipient, donor, surgical procedure, and outcome characteristics; b) the apparent stabilization of these trends in 2019 vs the 2016 to 2018 period; and c) the striking change in the rate of urgent transplant and, related to this, the differences in the use of the various circulatory support devices.

The trends in the last decade that have tended to stabilize in the most recent period include the higher proportion of women receiving transplants, the improved pretransplant renal function, the higher age of donors, the use of donors with a larger body size than recipients, the use of donors who have had a cardiac arrest, the greater use of the bicaval technique, and the shorter ischemia time. Nonetheless, the most striking novelty is related to the type of pretransplant circulatory support, with an increase in ventricular assist devices, a stabilization in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (the only such procedure available in some hospitals), and the almost complete disappearance of balloon pump therapy.6 Consequently, there was an increase in sternotomy history (standard for ventricular assist device implantation) and decrease in urgent transplants. These changes are related to modifications in the inclusion criteria for the urgent waiting list introduced halfway through 2017 by the Spanish National Transplant Organization after an analysis of data from the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry.7 In the new criteria, the need for balloon pump support is no longer considered a situation necessitating urgent transplant and the window has been limited for the inclusion of patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

As has been the norm in previous reports, survival continues to improve. Thus, in the last decade, the 5-year cumulative survival was 71.7%, similar to that reported by the registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.8 However, analysis of the survival curves of the most recent 3-year periods seems to show that outcomes have been stable since 2013. The differences in the first posttransplant year were stable among periods. Although the result was not significant, our findings indicate that the improvement since 2013 might be related to reduced death from primary graft failure and stabilization of that from infection.

CONCLUSIONSSpanish heart transplant activity in 2019 showed a stabilization of trends observed in the previous decade in terms of recipient, donor, surgical procedure, and outcome characteristics. Survival has been stable since 2013.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

| Hospital | Collaborators |

|---|---|

| Clínica Universitaria Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid | Javier Segovia-Cubero, Francisco Hernández-Pérez |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia | Soledad Martínez Penades, Mónica Cebrián Pinar, Raquel López Vilella, Ignacio Sánchez-Lázaro, Luis Martínez-Dolz |

| Hospital Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña | María J. Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Amador López Granados, Carmen Segura Saintgerons, Víctor Menjíbar Pareja, Francisco Carrasco Ávalos |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria | Manuel Cobo, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, José A. Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal Herrera |

| Hospital Gregorio Marañón (adults), Madrid | Zorba Blázquez, María Jesús Valero, Carlos Ortiz, Eduardo Zataraín, Adolfo Villa, Paula Navas, Manuel Martínez-Sellés |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | M. Dolores García Cosío, Laura Morán Fernández, Pedro Caravaca |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Vicens Brossa Loidi, Eulàlia Roig Minguell, Sonia Mirabet Pérez, Laura López López, Isabel Zegrí |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla | Diego Rangel Sousa |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Nicolas Manito Lorite, Carles Díez Lopez, Josep Roca Elias, Elena García Romero |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra | Gregorio Rábago Juan-Aracil |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | María Ángeles Castel, Marta Farrero |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | José Luis Lambert Rodríguez, Beatriz Díaz Molina, María José Bernardo Rodríguez, Cristina Fidalgo Muñiz |

| Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón (pediatric), Madrid | Manuela Camino López, Juan Miguel Gil Jaurena, Nuria Gil Villanueva |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris Garrido-Bravo, Domingo A. Pascual Figal, Francisco J. Pastor Pérez |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Portoles Ocampo, Marisa Sanz Julve |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de la Fuente Galán, Javier Tobar Ruiz, Amada Recio Platero |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Luis García-Guereta Silva, Álvaro González Rocafort, Carlos Labradero de Lera, Luz Polo López |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Ferrán Gran Ipiña, Dimpna C. Albert Brotons, Raúl Abella Antón |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria | Antonio García Quintana, María del Val Groba Marco |