The Spanish heart transplant registry updates its data annually. The current update presents the data for the year 2022.

MethodsWe describe the main clinical characteristics, treatments received, and survival outcomes including procedures performed in 2022, along with their trends since 2013.

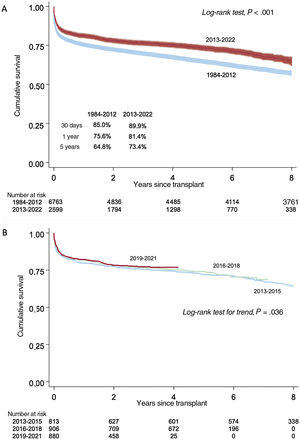

ResultsIn 2022, 311 cardiac transplants were performed, representing a 3.0% increase compared with 2021. Compared with previous years, no significant changes in demographic and clinical characteristics were observed in 2022, confirming the trends identified in the last decade. These trends indicate a decrease in urgent procedures and the use of circulatory support, particularly ventricular assist devices. In the last decade, survival rates at 1 and 3 years were 81.4% and 73.4% respectively, with a slight, nonsignificant improvement.

ConclusionsIn the last decade, there has been a stabilization in the characteristics of heart transplant procedures and their outcomes.

Keywords

The heart transplant field can consider 2022 to be the first year that was completely free of the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. A constrained influence of the pandemic on both activity and mortality outcomes was detected in previous reports of the Spanish heart transplant registry.1 The present report includes information on the procedures performed in 2022 and updates the historic series, particularly regarding mortality data. As is tradition, the main findings are centered on procedures performed in the last 10 years (2013-2022).

METHODSPatients and proceduresThe current report provides data on transplants performed in 2022. In addition, we have analyzed the changes over time in the characteristics of the series in the previous decade, stratified by 3-year periods (2013-2015, 2016-2019, and 2020-2021). The percentages of some characteristics in the last decade were analyzed by year, such as urgent transplants, type of pretransplant circulatory support, and donor age.

The inclusion and data updating procedures of the Spanish heart transplant registry have not undergone major changes from previous years.2 Crucially, the Spanish heart transplant registry was established as a registry of procedures (transplants performed), not of patients. Accordingly, a retransplanted patient generates 2 distinct records that are analyzed separately. Participation in the Spanish heart transplant registry is voluntary for all transplant teams operating in Spain. In a change from previous years, Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid) started in 2022 to include adult patients (age at transplant ≥ 18 years) undergoing transplants for congenital heart disease. Accordingly, the registry shows the same number of Spanish transplant centers, even though only 1 of these centers now performs pediatric transplants alone (table 1).

Centers participating in the Spanish heart transplant registry from 1984 to 2022 (by order of first transplant performed)

| 1. | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona |

| 2. | Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra |

| 3. | Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda (adult, cardiopulmonary), Majadahonda, Madrid |

| 4. | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria |

| 5. | Hospital Reina Sofía (adult and pediatric), Córdoba |

| 6. | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (adult and pediatric, cardiopulmonary), Valencia |

| 7. | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (adult and pediatric), Madrid |

| 8. | Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (1989-1994) |

| 9. | Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville |

| 10. | Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid |

| 11. | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (adult and pediatric), A Coruña |

| 12. | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona |

| 13. | Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid (adult and pediatric) |

| 14. | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias |

| 15. | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona |

| 16. | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia |

| 17. | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza |

| 18. | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid |

| 19. | Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (pediatric), Barcelona |

| 20. | Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

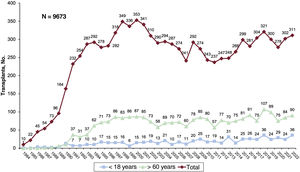

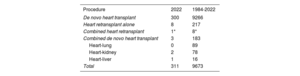

The total numbers and types of transplant performed in 2022 and in the entire series are summarized in table 2. In 2022, 311 transplants were performed; most (n=300) were de novo heart transplants. Thus, 9 retransplants (2.9%) were performed, as well as 1 combined heart-kidney transplant and 4 combined transplants (2 de novo heart-kidney transplants, 1 de novo heart-liver transplant, and 1 heart-kidney retransplant). By age, 28.9% of recipients (90 transplants) were older than 60 years and 11.6% (n=36) were younger than 18 years. Overall, the Spanish heart transplant registry has recorded 9673 procedures (figure 1).

Spanish heart transplant registry (1984-2022). Type of procedure

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation, whereas categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Differences among time periods were analyzed using a nonparametric test for temporal trends (Kendall τ) for categorical variables and a Wilcoxon test for trends for continuous variables.3 Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using a log-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<.05.

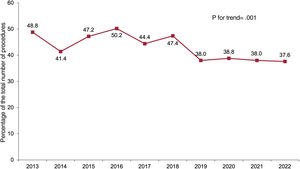

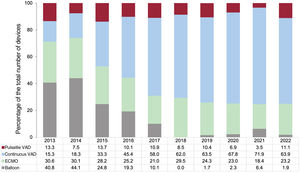

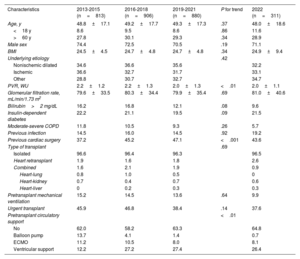

RESULTSRecipient characteristicsIn 2022, 311 transplants were performed, 9 (3.0%) more than in the previous year, which stabilizes the number of procedures performed at about 300 per year (figure 1). The main recipient characteristics in 2022 and from 2013 to 2022 are summarized in table 3. In the overall population, the mean recipient age has shown no significant changes in the last 10 years and remains 49.0 years (48.0 years in 2022). Similar stability was observed in recipients ≥ 18 years at transplant (53.2 years in the last decade, 53.3 years in 2022). There was a nonsignificant tendency for a higher proportion of female recipients in the last decade, which reached 28.9% in 2022. Similarly, a tendency was detected for improved clinical status among recipients, as well as for a lower proportion of patients with diabetes or with elevated bilirubin at transplant. This tendency was significant for pulmonary vascular resistance, which has decreased up to 2.0 Wood units, a finding maintained in 2022. The trend was confirmed in 2022 for a lower percentage of urgent transplants (37.6%), and the difference was significant compared with 2013 (P<.001) (figure 2). Since 2019, this percentage has consistently been less than 40%. The data from 2022 confirmed the highly significant temporal trends in the distribution of the type of immediate pretransplant circulatory support devices used (figure 3). In the last 5-year period, 562 patients (37.8% of the total number of patients transplanted in this period) were transplanted with some type of circulatory assist device. Most of these devices were continuous-flow ventricular assist devices (367 patients; 24.7% of all recipients), followed by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices (133 patients; 8.9%) and pulsatile ventricular assist devices (46 patients; 3.1%). The maginal use of balloon pump (16 patients; 1.1%) was maintained during this period. In 2022, these percentages largely matched those of the last 5-year period.

Recipient characteristics in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2013-2022)

| Characteristics | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | 2019-2021 (n=880) | P for trend | 2022 (n=311) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 48.8±17.1 | 49.2±17.7 | 49.3±17.3 | .37 | 48.0±18.6 |

| <18 y | 8.6 | 9.5 | 8.6 | .86 | 11.6 |

| >60 y | 27.8 | 30.1 | 29.3 | .34 | 28.9 |

| Male sex | 74.4 | 72.5 | 70.5 | .19 | 71.1 |

| BMI | 24.5±4.5 | 24.7±4.8 | 24.7±4.8 | .34 | 24.9±9.4 |

| Underlying etiology | .42 | ||||

| Nonischemic dilated | 34.6 | 36.6 | 35.6 | 32.2 | |

| Ischemic | 36.6 | 32.7 | 31.7 | 33.1 | |

| Other | 28.8 | 30.7 | 32.7 | 34.7 | |

| PVR, WU | 2.2±1.2 | 2.2±1.3 | 2.0±1.3 | <.01 | 2.0±1.1 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 79.6±33.5 | 80.3±34.4 | 79.9±35.4 | .69 | 81.0±40.6 |

| Bilirubin>2 mg/dL | 16.2 | 16.8 | 12.1 | .08 | 9.6 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 22.2 | 21.1 | 19.5 | .09 | 21.5 |

| Moderate-severe COPD | 11.8 | 10.5 | 9.3 | .26 | 5.7 |

| Previous infection | 14.5 | 16.0 | 14.5 | .92 | 19.2 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 37.2 | 45.2 | 47.1 | <.001 | 43.6 |

| Type of transplant | .69 | ||||

| Isolated | 96.6 | 96.4 | 96.3 | 96.5 | |

| Heart retransplant | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.6 | |

| Combined | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.9 | |

| Heart-lung | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Heart-kidney | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Heart-liver | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 15.2 | 14.5 | 13.6 | .64 | 9.9 |

| Urgent transplant | 45.9 | 46.8 | 38.4 | .14 | 37.6 |

| Pretransplant circulatory support | <.01 | ||||

| No | 62.0 | 58.2 | 63.3 | 64.8 | |

| Balloon pump | 13.7 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | |

| ECMO | 11.2 | 10.5 | 8.0 | 8.1 | |

| Ventricular support | 12.2 | 27.2 | 27.4 | 26.4 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Values are expressed as percentage or mean±standard deviation.

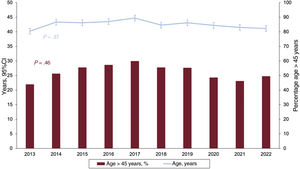

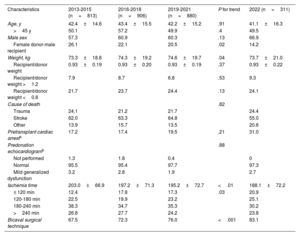

Donor and surgical procedure characteristics are summarized in table 4. Donor age has remained stable in the last decade (figure 4), at an average of 42.5±15.2 years in the last 10 years (41.1±16.3 years in 2022). Similar stability was seen for the percentage of suboptimal donors, that is, donors older than 45 years old, which has been 52.2% on average in the last decade (49.5% in 2022). At least until 2021, the only statistically significant characteristic was the use of larger donors (P for trend=.04), although this has not resulted in a particularly unfavorable donor-to-recipient weight ratio (> 1.2 or <0.8).

Donor characteristics and procedure times in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2013-2022)

| Characteristics | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | 2019-2021 (n=880) | P for trend | 2022 (n=311) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 42.4±14.6 | 43.4±15.5 | 42.2±15.2 | .91 | 41.1±16.3 |

| >45 y | 50.1 | 57.2 | 49.9 | .4 | 49.5 |

| Male sex | 57.3 | 60.9 | 60.3 | .13 | 66.9 |

| Female donor-male recipient | 26.1 | 22.1 | 20.5 | .02 | 14.2 |

| Weight, kg | 73.3±18.8 | 74.3±19.2 | 74.6±19.7 | .04 | 73.7±21.0 |

| Recipient/donor weight | 0.93±0.19 | 0.93±0.20 | 0.93±0.19 | .37 | 0.93±0.22 |

| Recipient/donor weight >1.2 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 6.8 | .53 | 9.3 |

| Recipient/donor weight <0.8 | 21.7 | 23.7 | 24.4 | .13 | 24.1 |

| Cause of death | .82 | ||||

| Trauma | 24.1 | 21.2 | 21.7 | 24.4 | |

| Stroke | 62.0 | 63.3 | 64.8 | 55.0 | |

| Other | 13.9 | 15.7 | 13.5 | 20.6 | |

| Pretransplant cardiac arresta | 17.2 | 17.4 | 19.5 | .21 | 31.0 |

| Predonation echocardiogramb | .88 | ||||

| Not performed | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Normal | 95.5 | 95.4 | 97.7 | 97.3 | |

| Mild generalized dysfunction | 3.2 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 2.7 | |

| Ischemia time | 203.0±66.9 | 197.2±71.3 | 195.2±72.7 | <.01 | 188.1±72.2 |

| ≤ 120 min | 12.4 | 17.8 | 17.3 | .03 | 20.9 |

| 120-180 min | 22.5 | 19.9 | 23.2 | 25.1 | |

| 180-240 min | 38.3 | 34.7 | 35.3 | 30.2 | |

| >240 min | 26.8 | 27.7 | 24.2 | 23.8 | |

| Bicaval surgical technique | 67.5 | 72.3 | 76.0 | <.001 | 83.1 |

Values are expressed as percentage or mean±standard deviation.

The most pertinent data regarding the donation process, which were consolidated in 2022, were donation after circulatory death (asystole) and ABO-incompatible transplantation. Donation after circulatory death was performed in 52 patients in 9 centers (4 patients in 2020, 11 in 2021, and 37 in 2022). In addition, 15 ABO-incompatible transplants were performed from 2018 to 2022, all in pediatric patients (4 in 2018, 2 in 2019, 2 in 2020, 4 in 2021, and 3 in 2022).

As seen in previous reports, the mean ischemia time has significantly decreased in the last 10 years (table 4) and was slightly longer than 3hours in 2022. This decrease was largely due to an increase in the number of procedures performed with an ischemia time less than 2hours. We continue to see significant growth in the bicaval technique, used in more than 80% of patients in 2022.

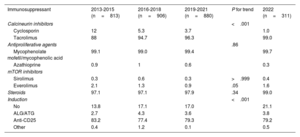

ImmunosuppressionTable 5 summarizes the trends related to the drugs used for induction immunosuppression. Data similar to those of the most recent years were obtained in 2022, although significant tendencies can still be detected when the comparison is extended to the beginning of the previous decade. Induction with anti-CD25 (currently only performed with basiliximab) and triple therapy with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (or mycophenolic acid), and steroids form the basis of the induction immunosuppressive therapy in the overwhelming majority of patients.

Induction immunosuppression in the Spanish heart transplant registry (2013-2022)

| Immunosuppressant | 2013-2015 (n=813) | 2016-2018 (n=906) | 2019-2021 (n=880) | P for trend | 2022 (n=311) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin inhibitors | <.001 | ||||

| Cyclosporin | 12 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 1.0 | |

| Tacrolimus | 88 | 94.7 | 96.3 | 99.0 | |

| Antiproliferative agents | .86 | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil/mycophenolic acid | 99.1 | 99.0 | 99.4 | 99.7 | |

| Azathioprine | 0.9 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| mTOR inhibitors | |||||

| Sirolimus | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | >.999 | 0.4 |

| Everolimus | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0.9 | .05 | 1.6 |

| Steroids | 97.1 | 97.1 | 97.9 | .34 | 99.0 |

| Induction | <.001 | ||||

| No | 13.8 | 17.1 | 17.0 | 21.1 | |

| ALG/ATG | 2.7 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | |

| Anti-CD25 | 83.2 | 77.4 | 79.3 | 79.2 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; anti-CD25, basiliximab, daclizumab; ATG, antithymocyte globulin.

Values are expressed as percentages.

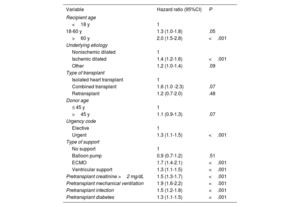

Survival in the 2013 to 2022 period was 81.4% in the first posttransplant year and 73.4% at 5 years. This rate is significantly higher than that seen in the entire historic series (figure 5A). No significant improvement in survival was detected in the last decade (figure 5B). However, numerically, 1-year survival has constantly improved: 79.7% from 2013 to 2015, 81.7% from 2016 to 2018, and 82.2% from 2019 to 2021. Some of the univariable predictors of mortality are summarized in table 6. The factors most strongly associated with mortality were those related to the recipient's pretransplant clinical status (need for advanced circulatory support or mechanical ventilation) and to comorbidity (age, pretransplant infection, diabetes or pretransplant renal failure, ischemic etiology).

Univariable analysis of survival by baseline characteristics of the recipient, donor, and procedure (2013-2022)

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age | ||

| <18 y | 1 | |

| 18-60 y | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | .05 |

| >60 y | 2.0 (1.5-2.8) | <.001 |

| Underlying etiology | ||

| Nonischemic dilated | 1 | |

| Ischemic dilated | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | <.001 |

| Other | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .09 |

| Type of transplant | ||

| Isolated heart transplant | 1 | |

| Combined transplant | 1.6 (1.0 -2.3) | .07 |

| Retransplant | 1.2 (0.7-2.0) | .48 |

| Donor age | ||

| ≤ 45 y | 1 | |

| >45 y | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | .07 |

| Urgency code | ||

| Elective | 1 | |

| Urgent | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.001 |

| Type of support | ||

| No support | 1 | |

| Balloon pump | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | .51 |

| ECMO | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | <.001 |

| Ventricular support | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant creatinine >2 mg/dL | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant mechanical ventilation | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant infection | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | <.001 |

| Pretransplant diabetes | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

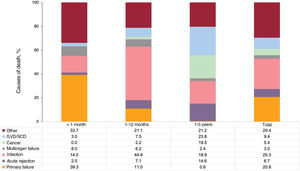

The specific causes of death in the first 5 posttransplant years were primary graft failure (23.2%) and infection (21.0%) (figure 6). As expected, the main causes of death were primary graft failure in the first posttransplant month (39.3%) but infection between 2 and 12 months (44.9%). Acute rejection was the cause of death in 7.1% of patients between the 2nd and 12th posttransplant months. Although rejection was the fourth cause of death in the first 5 posttransplant years, its prevalence was not negligible after the first year (14.6% of patients). After the first posttransplant year, the most frequent causes of death were graft vascular disease/sudden cardiac death (23.8%) and cancer (19.5%).

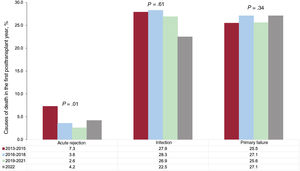

The last decade has shown a significant decrease in rejection as the cause of death in the first year (from 7.3% from 2013 to 2015 to 2.6% from 2019 to 2021), although an uptick was detected in 2022 (4.2% of all deaths). However, the prevalences of primary graft failure and infections as causes of death have remained stable in the last 10 years (figure 7).

DISCUSSIONFrom the perspective offered by the sustained effort of the Spanish heart transplant registry, analysis of the temporal trends in recent years appears to show the stability of heart transplantation activity in Spain regarding the characteristics of recipients, donors, surgical procedures, and immunosuppressive therapy. In this regard, the prototypic patient in Spain in recent years has been a man in 3 of every 4 cases, aged about 50 years and who, in slightly more than one third of cases, undergoes an urgent transplant, typically with a ventricular assist device. The transplant was performed in half of the cases with a donor who would conventionally be considered suboptimal. In addition, we may be seeing signs of effort to more strictly select recipients with a better risk profile (tendency for fewer recipients with pretransplant diabetes) and better general status immediately before transplant (improved bilirubin values and fewer and fewer patients on mechanical ventilation every year). Notably, the efforts of the organ procurement system and surgical teams have resulted in progressively shorter ischemia times and extensive use of the bicaval technique. No major novelties have been seen in relation to immunosuppressants, and most patients are induced with basiliximab and almost all receive triple therapy based on tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids. In this general framework, the survival outcomes can be considered equivalent to those of other international registries.4 The 1-year survival exceeds 80% and three quarters of patients are still alive at 5 years, with the median survival of transplant recipients exceeding 12 years in the last decade.

Currently, ongoing work within the heart transplant field is aimed at improving the balance between procedure availability and futility and at increasing the supply of donors. The first aspect includes the recent modification of the organ allocation criteria of the Spanish National Transplant Organization,5 in which the analysis provided by the Spanish heart transplant registry played a decisive role. The second aspect includes ABO-incompatible transplantation, a technique that is being adopted worldwide and ever more frequently in Spain6 and that constitutes an opportunity to combat the traditional scarcity of appropriate donors for pediatric patients. This area also encompasses donation after circulatory death. The first of this type of donation in Spain was recorded at the end of 2020 and the technique is showing an almost exponential growth. It is used for both pediatric and adult transplantation. In 2022, 9 centers in Spain already have a program with these characteristics, and the procedure is expected to represent a true revolution in the expansion of the donor supply, given that it exhibits equivalent outcomes to traditional donation after brain death.7

LimitationsThis study has the typical limitations inherent to a registry of unaudited reports.

CONCLUSIONSClinical characteristics and survival outcomes have remained stable in Spain in recent years. A notable increase was detected in ABO-incompatible transplantation techniques and donation after circulatory death.

FUNDINGThis work has not received any funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors have contributed to the data collection, have critically revised the manuscript, and have approved its publication in the current form. F. González-Vílchez drafted the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

| Center | Collaborators |

|---|---|

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria | Manuel Cobo-Belaustegui, Miguel Llano-Cardenal, José Antonio Vázquez de Prada, Francisco Nistal-Herrera, Cristina Castrillo |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | Beatriz Díaz-Molina, Vanesa Alonso-Fernández, Cristina Fidalgo-Muñiz, Antonio Adeba-García |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville | Antonio Grande-Trillo, Diego Rangel-Sousa |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Vicens Brossa, Sonia Mirabet, Laura López |

| Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona | Marta Farrero-Torres, Pedro Caravaca, Eduard Solé |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | José González-Costello, Carles Díez-López, Fabrizio Sbraga, Pablo Catalá-Ruiz, Lorena Herrador |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (adults), Madrid | Zorba Blázquez, Iago Sousa, Javier Castrodeza, Eduardo Zataraín, Adolfo Villa y Manuel Martínez-Sellés |

| Hospital Univesitari i Politècnic La Fe, Valencia | Raquel López-Viella, Víctor Donoso-Trenado, Soledad Martínez-Penades, Ignacio Sánchez-Lázaro |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Francisco Carrasco-Ávalos |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid | Manuel Gómez-Bueno, Javier Segovia-Cubero, Cristina Mitroi, Mercedes Rivas-Lasarte, Sara Lozano-Jiménez, Jose María Viéitez-Flórez |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | María Dolores García-Cosío, Laura Morán-Fernández, Javier González Martín, Irene Marco-Clement |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, A Coruña | Maria Jesús Paniagua-Martín, Eduardo Barge-Caballero, Gonzalo Barge-Caballero, David Couto-Mallón, Daniel Enríquez-Vázquez |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz (pediatric), Madrid | Luis García-Guereta Silva, Álvaro González-Rocafort, Carlos Labrandero de Lera |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz (adults), Madrid | Inés Ponz de Antonio, Adriana Rodríguez-Chaverri |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (pediatric), Madrid | Manuela Camino-López, Nuria Gil-Villanueva, Juan Miguel Gil-Jaurena |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid | Luis de la Fuente-Galán, Javier Tobar-Ruiz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia | Iris P. Garrido-Bravo, Francisco J. Pastor-Pérez, Domingo A. Pascual-Figal |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Teresa Blasco-Peiró, Ana Pórtoles-Ocampo, Ana Marcén-Mirabete |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra | Gregorio Rábago-Juan-Aracil, Rebeca Manrique-Antón, Leticia Jimeno-San Martín |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Antonio García-Quintana, María del Val Groba-Marco, Mario Galván-Ruiz, Miguel Fernández de Sanmamed-Girón |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Ferrán Gran-Ipiña, Paola Dolader |