Our aim was to analyze the pacemaker implantations and replacements reported to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2012 with special reference to the selection of pacing modes.

MethodThe analysis was based on information provided by the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card.

ResultsData were received from 115 hospitals, with a total of 12 856 cards. An estimated 745.8 pacemaker generators and 53.1 resynchronization devices were implanted per million population. Active fixation leads were implanted in more than 70% of the patients; of these leads, more than 20% were safe for use with magnetic resonance. The most common electrocardiographic indication for pacemaker implantation was atrioventricular block (56%). In all, 28% of the patients with sick sinus syndrome were paced in VVIR mode.

ConclusionsThe use of conventional pacemakers remained stable, whereas the implantation of resynchronization devices increased. Active fixation leads are now employed in most patients. The findings of this study confirm the higher incidence of implantation in men and at an earlier age due to the higher rate of conduction disorders. Age is a factor that influences the choice of the appropriate pacing mode.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONThe present report provides the most relevant data on cardiac stimulation with pacemakers documented in 2012, one of the objectives of the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos. This report illustrates the realities of clinical practice, allowing estimation of the degree of compliance with the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines,1–4 the incorporation of technological advances, comparisons of different aspects of pacing with the findings in other registries or activity in Spain, and assessment of the quality of–or possible improvements in–cardiac pacing. Current trends in major aspects of pacing are reported, although the data corresponding to certain items are not available for every year due to changes in the software and computer application of the database.

Since the first official report was issued in 1997,5 this information has been published annually6–15 with a similar structure in the Revista Española de Cardiología. The registry has continuous records dating back to 1994, although the first data were obtained from a survey published in 1989.16

A number of graphs providing information covering all the years since 1999 are available on the website of the Working Group on Cardiac Pacing.17

METHODSThe analysis of the pacemaker registry was based on information from the following sources.

Report of the Spanish Institute of StatisticsFor calculations based on census data, we used the latest update from the Spanish Institute of Statistics, dated January 2012. Thus, there may be a slight discrepancy in the population, as the number of residents in Spain tended to decline over that year; according to preliminary census data, the population has decreased by an estimated 372 000 inhabitants compared with 2011.18

Information Provided by the Distributors of the DevicesAccording to current Spanish legislation, it is mandatory to report all the procedures carried out to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry to enable supervision for possible alerts, etc. (Royal Decree 1616/2009 dated 26 October, regulating active implantable medical devices). The Spanish registry does not receive all the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Cards (EPPIC); thus, the total number of pacemakers used and data on their distribution by autonomous community is obtained through collaboration among the companies supplying the devices, information that they also convey to the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED).

European Pacemaker Patient Identification CardsOnly the information provided on the EPPIC is processed: age, sex, and coded fields for symptoms, etiology, electrocardiographic indications, pacing mode, implantation or explantation of leads or the generator, and lead extraction. The EPPIC is completed in the hospital after implantation and a copy is automatically generated for the Spanish Pacemaker Registry. The information can also be transferred electronically (such as the databases of each center) with the necessary guarantees. The Working Group on Cardiac Pacing developed a proprietary database10 to facilitate and standardize data collection and processing that has not achieved the objective for which it was designed. Thus, an online portal is being created for the transfer, automation, and extension of the EPPIC.

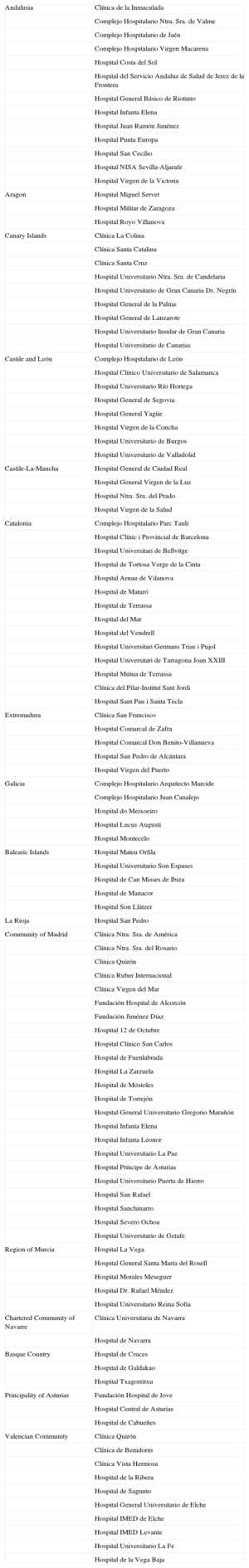

Sample AnalyzedIn 2012, a total of 12 856 cards reporting implantations or replacements of pacemaker generators were received (a decrease of 3.8% with respect to 2011),15 corresponding to 115 hospitals (Table), which represent 36.8% of all the generators employed. Two nurses with extensive experience in the follow-up of pacing devices cleaned the data using a purpose-built software application. The results correspond to the analysis of the sample described above. The structure is the same as that of previous publications.

Public and Private Hospitals That Submitted Data to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2012, Grouped According to Autonomous Community

| Andalusia | Clínica de la Inmaculada |

| Complejo Hospitalario Ntra. Sra. de Valme | |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Virgen Macarena | |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | |

| Hospital del Servicio Andaluz de Salud de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital General Básico de Riotinto | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez | |

| Hospital Punta Europa | |

| Hospital San Cecilio | |

| Hospital NISA Sevilla-Aljarafe | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Victoria | |

| Aragon | Hospital Miguel Servet |

| Hospital Militar de Zaragoza | |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | |

| Canary Islands | Clínica La Colina |

| Clínica Santa Catalina | |

| Clínica Santa Cruz | |

| Hospital Universitario Ntra. Sra. de Candelaria | |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | |

| Hospital General de la Palma | |

| Hospital General de Lanzarote | |

| Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria | |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | |

| Castile and León | Complejo Hospitalario de León |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | |

| Hospital General de Segovia | |

| Hospital General Yagüe | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Concha | |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos | |

| Hospital Universitario de Valladolid | |

| Castile-La-Mancha | Hospital General de Ciudad Real |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz | |

| Hospital Ntra. Sra. del Prado | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| Catalonia | Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí |

| Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona | |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | |

| Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta | |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova | |

| Hospital de Mataró | |

| Hospital de Terrassa | |

| Hospital del Mar | |

| Hospital del Vendrell | |

| Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol | |

| Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII | |

| Hospital Mútua de Terrassa | |

| Clínica del Pilar-Institut Sant Jordi | |

| Hospital Sant Pau i Santa Tecla | |

| Extremadura | Clínica San Francisco |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | |

| Hospital Comarcal Don Benito-Villanueva | |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara | |

| Hospital Virgen del Puerto | |

| Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Arquitecto Marcide |

| Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo | |

| Hospital do Meixoeiro | |

| Hospital Lucus Augusti | |

| Hospital Montecelo | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Mateu Orfila |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | |

| Hospital de Can Misses de Ibiza | |

| Hospital de Manacor | |

| Hospital Son Llàtzer | |

| La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro |

| Community of Madrid | Clínica Ntra. Sra. de América |

| Clínica Ntra. Sra. del Rosario | |

| Clínica Quirón | |

| Clínica Ruber Internacional | |

| Clínica Virgen del Mar | |

| Fundación Hospital de Alcorcón | |

| Fundación Jiménez Díaz | |

| Hospital 12 de Octubre | |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada | |

| Hospital La Zarzuela | |

| Hospital de Móstoles | |

| Hospital de Torrejón | |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Infanta Leonor | |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro | |

| Hospital San Rafael | |

| Hospital Sanchinarro | |

| Hospital Severo Ochoa | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital La Vega |

| Hospital General Santa María del Rosell | |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer | |

| Hospital Dr. Rafael Méndez | |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Hospital de Navarra | |

| Basque Country | Hospital de Cruces |

| Hospital de Galdakao | |

| Hospital Txagorritxu | |

| Principality of Asturias | Fundación Hospital de Jove |

| Hospital Central de Asturias | |

| Hospital de Cabueñes | |

| Valencian Community | Clínica Quirón |

| Clínica de Benidorm | |

| Clínica Vista Hermosa | |

| Hospital de la Ribera | |

| Hospital de Sagunto | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | |

| Hospital IMED de Elche | |

| Hospital IMED Levante | |

| Hospital Universitario La Fe | |

| Hospital de la Vega Baja |

In 2012, according to the data provided to the registry by the distributors, a total of 34 919 pacemaker generators were implanted or replaced, including 712 biventricular devices for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) without defibrillation capacity (CRT-P). As has occurred on other occasions, these data differ slightly from those submitted to the EUCOMED, which reported a total of 35 426 pacemaker generators, of which 709 were CRT-P devices.

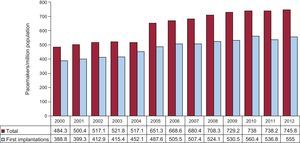

According to the data of the Spanish Institute of Statistics, the population was 46 818 000 inhabitants, 23 719 000 women and 23 099 000 men. Thus, according to the data of the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, 745.8 pacemaker generators were implanted per million population (Fig. 1), and the rate of pacemaker implantation by sex was 634 per million women and 860 per million men.

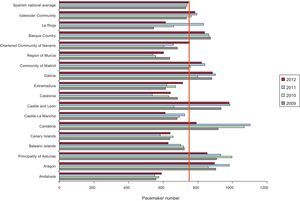

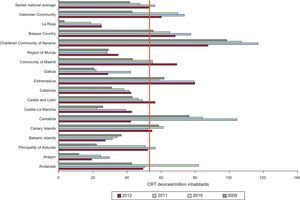

As in previous reports,10–15 the number of devices per million population differed widely from one autonomous community to another. In 2012, over 900 units per million population were implanted in Castile and León, followed by Aragon and Galicia (Fig. 2).

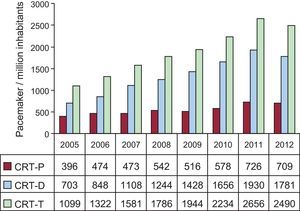

Biventricular PacingThe rate of CRT device implantation was 53.1 units per million population (56.2 in 2011), showing a decrease for the first time with respect to peak use (Fig. 3), even though Spain is one of the European countries with the lowest implantation rates.19,20 The decrease corresponded both to units with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (CRT-D) and those without (CRT-P), but was more marked in the former. The rate of implantation of low-energy devices was 15.1 units per million population.

According to the registry, 1.5% of the total number of pacemakers were biventricular devices, which were used in 1.2% of first implantations and in 2.4% of replacements.

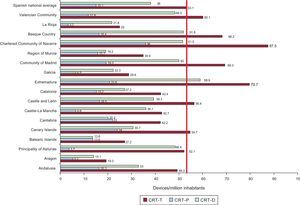

There were also marked differences among autonomous communities in the use of CRT. The Chartered Community of Navarre reported the largest number of implantations per million population, followed in descending order by Extremadura, the Community of Madrid, and the Basque Country (Fig. 4); data for recent years are shown in Figure 5.

Cardiac resynchronization devices implanted per million population in 2012, showing the Spanish national average (vertical red line) and distribution by autonomous community. CRT-D, biventricular device with defibrillation capability; CRT-P, low-energy biventricular device; CRT-T, total number of cardiac resynchronization devices.

The mean age of patients undergoing pacemaker implantation or generator replacement was 77.3 years; the mean age was 77 years at first implantation and was 77.9 years at generator replacement.

The highest implantation rate (40.5%) corresponded to the 80 to 89 year age group, followed in descending order by 70 to 79 years (35.6%), and 60 to 69 years (12.7%). For replacements, the order of frequency in the different age groups was similar, with 42.5% between 80 and 89 years, 28.2% between 70 and 79 years, and 10.9% between 60 and 69 years.

A sex difference was observed in the mean age at implantation, which was somewhat younger in men (76.4 years) than in women (78.1 years).

The use of pacemakers was greater in men (56.8%), both in first implantations (57.5%) and in replacements (54.8%); these findings are similar to those of other years analyzed.5–15

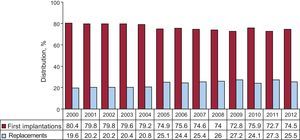

Type of ProcedurePacemaker ImplantationCardiac stimulation with a pacing system was indicated in 74.5% of the patients included in the registry; there were 555 first implantations per million population, representing an increase of 18.2 devices per million population with respect to 2011, but this rate was lower than that of 2010 (Fig. 1).

Replacements and Their CausesGenerator replacements accounted for 25.5% of procedures, a percentage that was somewhat lower than in 2011, the year when the rate peaked (Fig. 6).

Replacements that combined substitution of a lead due to changes in its electrical characteristics or implantation of an improved device accounted for 1.6% of all procedures, similar to the rate in previous years in which data were available.

The most common cause for generator replacement was battery depletion as it reached the end of its life (91.3%). This was followed in order of frequency by infection or erosion of the generator pocket (3%), elective replacement (2.6%), premature battery depletion (1%) (it was not possible to determine whether this was due to high thresholds or to a shorter than expected duration of the battery life), change associated with lead failure (0.7%), and improvement in the pacing mode for hemodynamic reasons (0.6%). A minimal proportion (0.1%) of the replacements was attributed to a major or minor defect in the generator.

Pacing LeadsPolarityNearly all the leads (99.8%) were bipolar; 99.95% of those implanted in the right atrium and 99.85% of those implanted in the right ventricle (RV) were of this type. Of the leads used for epicardial pacing via the coronary sinus (for CRT or elective for other reasons, such as the presence of a mechanical tricuspid valve prosthesis), 72.7% were bipolar, a type of lead that is increasingly being used at this site (66% in 2011).

The distribution of the unipolar leads employed in 2012, 0.2% of all those placed, was as follows: 50% were implanted in the RV, 34% were used for pacing via the coronary sinus, 7.7% were placed in the right atrium, and the remainder consisted of epicardial leads used in different cardiac surgical procedures.

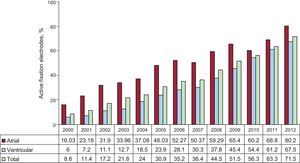

Mode of Lead FixationActive fixation of the distal electrode by means of a retractable helix, to secure it to the myocardium, is being increasingly used and was the fixation mechanism in 70.5% of the leads. It was used in 80.2% of atrial leads, compared with 67.5% of ventricular leads (Fig. 7).

Patient age was not a determining factor in the choice of the fixation mechanism. The analysis of the leads implanted in 2 groups of patients with a cutoff age of 80 years showed that active fixation was used in 68.3% of the patients older than 80 years (62.8% in 2011) and in 71.3% of those aged 80 years or less (63.5% in 2011); equally, there were no differences in age according to the chamber paced: the atrium in 80.5% of patients older than 80 years and 79.5% in those aged 80 years or less, and the ventricle (RV) in 66.3% and 68.2%, respectively.

Magnetic Resonance-safe LeadsOne of the latest advances in cardiac pacing systems is their compatibility with (MR) imaging. Leads especially designed to prevent possible alterations during the performance of MR represented 21.9% of those implanted, with similar percentages in the 2 age groups; 24.6% of those placed in the atrium and 20.6% of the ventricular leads were MR-safe. These percentages may have been higher because some of the standard leads passed subsequent tests for safe use in the MR environment. This MR imaging study should not be performed until 6 weeks after implantation.

Extraction and Replacement of Pacing LeadsAccording to our data, 1.6% of the leads implanted in 2012 corresponded to extractions. The most common indications were infection or ulceration (57%), lead fracture or insulation defects (12.5%), sensing problems and myopotentials (10%), lead migration (7.5%), unspecified (5%), and exit block (2.5%).

In 2012, 1.8% of the reported procedures involved implantation of a novel electrode lead. Another 1.6% corresponded to procedures associated with generator replacement to improve hemodynamic function or due to damage to the lead prior to or during the surgical procedure. Only 0.2% of the interventions were performed exclusively for lead replacement.

Symptoms, Etiology, and Electrocardiographic Abnormalities Prior to ImplantationSymptomsThe clinical symptoms leading to implantation were, in order of frequency: syncope (in 41.2% of patients), dizziness (26.6%), dyspnea or signs of heart failure (15.3%), bradycardia (10.8%), asymptomatic/prophylactic (2.4%), chest (1.2%), tachycardia (1.1%), brain dysfunction (0.8%), and resuscitated sudden death (0.2%). Implantation was performed in asymptomatic patients or for prophylactic reasons in 2.4% of patients. These findings are similar to those recorded in previous years.4–15

EtiologyThe most common indication for implantation of a cardiac pacing system was “fibrosis of the conduction system” (43.3%), whereas the etiology was unknown in 41.3% of patients. These 2 contexts, with a combined incidence of 84.6%, should be grouped together since the former etiology was assigned after exclusion of other causes. Other etiologies were ischemia (5.4%), valve disease (2.8%), and the iatrogenic-therapeutic context (2.7%). Atrioventricular node ablation was involved in 1% of the latter cases, interrupting the decrease in the incidence of this factor in recent years.11–15 Neurally-mediated mechanisms accounted for 1.2% (a rate similar to that of 2011) and vasovagal syncope for 0.3%. The etiology of implantation has varied little over the years.

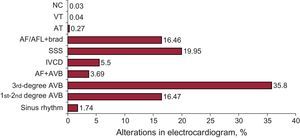

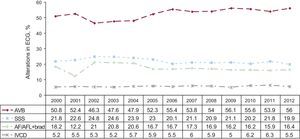

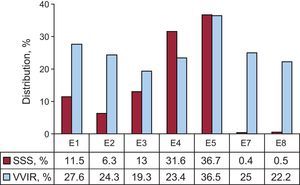

Abnormal Electrocardiographic FindingsThe most common electrocardiographic abnormality prior to implantation was third-degree atrioventricular conduction block (AVB) (35.8%). The AVB group comprised 56% of patients and sick sinus syndrome (SSS) in its different forms, excluding atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter (AF/AFL) with bradycardia, 19.9%. Figures 8 and 9 show graphs detailing the groups and the changes in the percentages over time.

Incidences of electrocardiographic abnormalities prior to implantation in 2012. AF+AVB, atrial fibrillation with atrioventricular block; AF/AFL+brad, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with slow ventricular response; AT, atrial tachycardia; AVB, atrioventricular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbance; NC, not coded; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Incidences (%) of electrocardiographic abnormalities prior to implantation from 2000 to 2012. AF/AFL+brad, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with slow ventricular response; AVB, atrioventricular block; ECG, electrocardiogram; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbance; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

With regard to sex, the incidence of AVB and intraventricular conduction disturbances (IVCD) to be higher among men; the incidence of SSS was somewhat higher in women9–15; thus, the ratio of men to women was 1.3 for AVB, 2.6 for IVCD, and 0.9 for SSS.

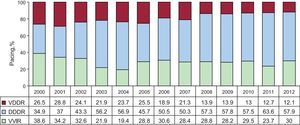

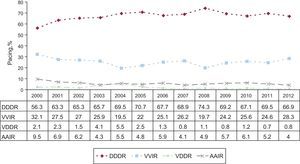

General Pacing ModesAtrial Pacing (AAIR). Overall, 2012 was the year in which the AAIR mode was least used (0.7% of all the generators) (Fig. 10), a percentage that was lower in first implantations (0.5%) than in replacements (1%).

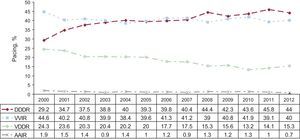

Single-chamber Ventricular Pacing (VVIR). This mode was employed in 40% of procedures, in 41.7% of first implantations and 35.3% of the replacements. In a significant percentage of the patients in whom this pacing mode was employed (estimated to be over 22%), it could be used in synchrony with the atrium,1,2,21 in accordance with published electrocardiographic indications. Its distribution according to the different indications and factors that can influence mode selection will be analyzed later in this report.

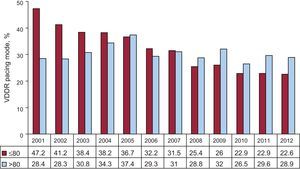

Sequential Pacing With a Single Lead (VDDR). This mode accounted for 15.3% of the pacemakers placed, with a marked difference between first implantations (12.2%) and replacements (23.9%) (Fig. 10).

Sequential Pacing With 2 Leads (DDDR). This was the most widely employed mode (44%) both in first implantations (45.5%) and in replacements (39.7%). When all atrial-based pacing was grouped together, the proportion rose to 59.9% (Fig. 10). One or more biosensors were added to monitor changes in heart rate in 84% of patients.

Biventricular Pacing. In 2012, pacing for the treatment of heart failure decreased by 6.2% with respect to the previous year. The use of CRT-P decreased both in terms of the number of devices placed (17 fewer than in 2011) and in the number per million population (0.2% lower than in 2011). The greatest decrease in the utilization of CRT corresponded to CRT-D, 212 units. The overall number of CRT devices (53.1 units per million population) remained far from the average both in Europe as a whole19,20 and in those European countries that report their activity to the EUCOMED.21

Selection of the Pacing ModePacing in Conduction DisturbancesPacing in Atrioventricular Block. To analyze the degree of compliance with the most strongly recommended pacing modes, only patients in sinus rhythm are studied, and the group with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia with AVB is excluded.1,2,4,21

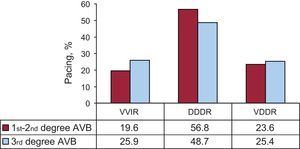

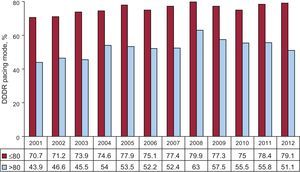

Atrial synchronous pacing was the most widely used mode (75.2%: DDDR, 51.1%; VDDR, 24.1%). In the latter mode, the percentage was the same as in 2010, but showed a slight decrease with respect to 201114 (Fig. 11).

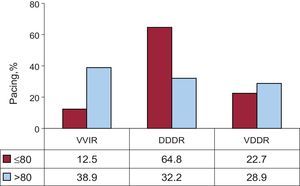

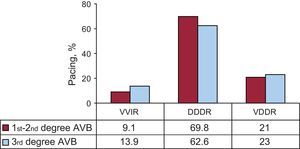

The distribution of atrial synchronous pacing modes into 2 age groups (cutoff at 80 years) demonstrated a marked difference: these modes were used in 87.5% of the patients aged 80 years or less and in 61.1% of those older than 80 years of age due to the more widespread use of the DDDR mode; the VDDR mode was more frequently employed in the most elderly patients (Fig. 12).

The analysis of atrial-based pacing by degree of AVB (first- and second-degree or third-degree) showed a higher percentage in first- and second-degree AVB (80.4%) than in third-degree AVB (74.1%) due to more frequent use of the DDDR mode in the former group (Fig. 13). These findings are similar to those of previous years. The differences between these AVB groups were maintained regardless of the age (cutoff at 80 years) (Figs. 14 and 15).

Following a decline in recent years, the use of the VDDR mode leveled off, especially in the younger age group (Fig. 16).

The choice of pacing mode was somewhat influenced by sex in both age groups. As in the other 2 years analyzed,14,15 DDDR pacing was more widely used in men than in women, whereas the VDDR mode was more often employed in women. The overall rate of the application of sequential pacing was 4.5% lower in the group of younger women.

The VVIR pacing mode continued to be used in a high percentage of patients with AVB who were assumed to be in sinus rhythm (24.8%). This mode was more often chosen for elderly patients (Fig. 17), as well as in patients with third-degree block (Fig. 13), and somewhat more in women.

Intraventricular Conduction Disturbances. Sequential pacing was employed in 70% of patients with IVCD, which represents a decline with respect to 2011 due to a reduction in the use of the DDDR mode, which was that most frequently employed (57.9%). The use of the VDDR mode remained constant (12.1%).

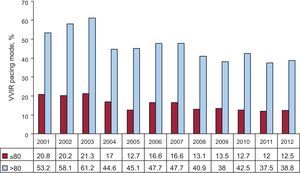

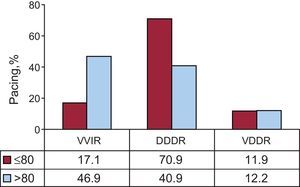

Single-chamber VVIR pacing represented 30% (Fig. 18). Age was again a determining factor in mode selection; in fact, the VVIR mode was indicated in 46.9% of patients older than 80 years of age compared with 17.1% of those aged 80 years or less. The VDDR mode continued to be that least influenced by age, with a similar rate of application in both age groups (11.9% and 12.2%, respectively) (Fig. 19).

In this group, sex did not influence the choice of atrial synchronous pacing, which was used in 85.5% of men aged 80 years or less and in 87.5% of the women in that age group.

In the treatment of ventricular dysfunction, CRT-P devices accounted for 10.5% of the units implanted for this disease. There were age-related differences: these devices were implanted in 17.2% of the patients aged 80 years or less and in 2.3% of older patients. In the younger group, they were more often used in women (32.1% vs 12.5% of the men).

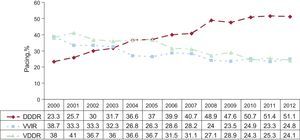

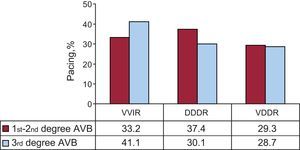

Pacing in Sick Sinus Syndrome. For the study of pacing mode choice,1,2,21 we divided the patients into 2 groups: those who had permanent AF/AFL with bradycardia and those who theoretically remained in sinus rhythm.

Pacing in Sick Sinus Syndrome With Permanent Atrial Tachyarrhythmia. The pacing mode was VVIR in 94.5% of the patients. There remained groups representing 4.5% and 1% in which DDDR and VDDR pacing, respectively, was chosen. This can only be explained by the fact that these patients were going to be reverted to sinus rhythm, as observed in previous years.

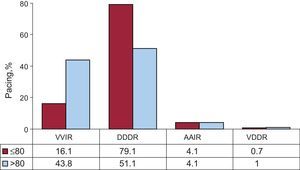

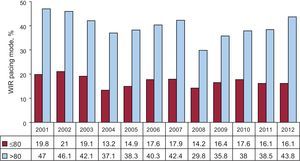

Pacing in Sick Sinus Syndrome in the Presence of Sinus Rhythm. The most common pacing mode (66.9%) was DDDR. The use of the AAIR mode (4%) was at its lowest level in recent years. Together, these 2 modes of atrial pacing, those best indicated1,2,21 for this group of patients, represented 70.9% of the devices (Fig. 20). For the remaining patients, the VVIR mode was used in 28.3% (the highest percentage since 2001) and the VDDR mode in 0.8%. These 2 modes are less suitable for this type of rhythm disturbance. The high incidence of VVIR pacing was observed in association with each of the different electrocardiographic signs of SSS, ranging from 19.3% in SSS with sinus arrest to a maximum of 36.5% in tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome (Fig. 21). It is difficult to understand the widespread use of VVIR pacing in tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome; we consider that it could be due to a classification error, and that this group included patients with episodes of permanent AF and phases of fast-slow ventricular response who should have been in the AF/AFL with bradycardia group. The analysis of the influence of age in the 2 groups defined above, with a cutoff at 80 years, showed that VVIR pacing was chosen in 16.1% of patients aged 80 years or less and in 43.8% of those in the older group (Fig. 22). Pacing modes capable of sensing and pacing the atrium were employed in 83.2% and 55.2% of these age groups, respectively. There remained a small percentage in which the VDDR mode was used (0.7% and 1%, respectively) (Fig. 22). Age has been found to influence the choice of pacing mode over the years (Figs. 23 and 24), but not the use of AAIR, which is the same in both age groups. In 2012, there was no evidence of an influence of sex on the choice of pacing mode. The VVIR mode was employed in the same percentage of men as women in the group of patients aged 80 years or less (16%) and in 38% and 39%, respectively, in the older age group. The AAIR mode was used somewhat more (4.6%) in older women, considering its limited overall acceptance.

Distribution of the different electrocardiographic signs of sick sinus syndrome by the code provided by the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card, and the use of the single-chamber ventricular pacing. E1, sick sinus syndrome not specified; E2, exit block; E3, sinus arrest; E4, bradycardia; E5, bradycardia-tachycardia; E7, interatrial block; E8, chronotropic incompetence; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VVIR, single-chamber ventricular pacing. E6 (atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with bradycardia) has been excluded.

In 2012, home monitoring or follow-up was carried out in 3.8% of conventional pacemakers, in 7% of the CRT-P devices, and in 52% of the CRT-D devices.

DISCUSSIONIn 2012, there was a slight increase in the use of conventional pacemaker generators, for a total of 745 units per million population, although the rate was lower than the average for Europe as a whole.20 Notable was the decrease, for the first time, in the use of CRT devices, both in absolute number and in units per million population, in low- and high-energy devices, mainly in the latter, even though Spain is one of the European countries with the lowest rates of implantation of CRT devices per million population.19,20,22 There is no clear explanation, although the indications are possibly restricted because of the current economic situation but, under these circumstances, we would expect there to be an increase in the number of devices without an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. The regional differences in the rates of implantation of conventional pacemakers and CRT generators, very similar to those in previous years analyzed10–15 and in other registries,23 in Spain are due, in part, to differences in the mean age of the populations10 and the possibly differing densities of arrhythmia and heart failure units.

The mean age at first implantation showed a gradual increase, reaching 77 years, due to population aging. A higher incidence of pacemaker implantation is still being recorded in younger men due to the greater prevalence of degeneration of the conduction system in these individuals, which is lower in SSS.

Active fixation leads were employed in 70% of procedures, and were more frequently placed in atrium. The increase in their use is due in part to their good electrical performance and isodiametric design, which facilitates their eventual extraction and the possibility of pacing alternative sites, such as the ventricular septum, where there is evidence that the ejection fraction is better preserved,24 or atrial septum to reduce the incidence of AF in interatrial conduction disturbances.

Pacing systems compatible with MR were employed in over 20% of procedures, although it is impossible to foresee which patients will require this imaging study in the future. The incorporation of this improvement as a standard feature in all pacing systems would be a desirable measure.

In SSS, there was a certain deterioration of the quality of pacing, concentrated in the most elderly patients, with the highest percentage of VVIR pacing in recent years, a mode that can produce symptomatic retrograde conduction, a higher incidence of AF, or a higher percentage of ventricular pacing with a future risk of ventricular dysfunction (Fig. 20). The choice of pacing mode was influenced by age (Fig. 23), but not by sex.

In Spain, acceptance of AAIR pacing for SSS has always been limited, as in other countries,25 but its use in 2012 was further reduced, possibly due to the influence of the recent DANPACE trial,26 which indicated that it offers no advantages over DDDR and is associated with a higher rate of reoperations and incidence of AF. Nevertheless, we feel that it is a mode that should be taken into consideration because of its lower cost and fewer complications, especially in young patients without IVCD.21

The VDDR pacing mode continued to be considered an alternative for conduction disturbances27,28 and was indicated in 24% of patients with AVB, a rate that has leveled off in the last 4 years. An estimated 5276 units are placed annually.

As in SSS, in AVB with sinus rhythm, VVIR pacing continued to be used in a large percentage of patients, especially in elderly patients and in third-degree AVB, based on studies that show the absence of an effect on survival, but do not consider other aspects such as quality of life or the incidence of heart failure.29

Home monitoring and follow-up have been shown to be an effective and efficient alternative20 to office follow-up visits, but they are still far from being widespread among our patient population, both in patients with conventional pacemakers (3.8%) and in those with high-energy cardiac resynchronization devices (52.4%).

CONCLUSIONSIn 2012, the use of conventional pacemakers remained steady, but there was a decrease in the number of resynchronization devices. Pacing with active fixation leads continued to gain acceptance. This report confirms the greater frequency of pacemaker placement in men due to the higher prevalence of conduction disturbances. The incidence of SSS was higher in women. Age was a determining factor in the choice of the VVIR pacing mode in patients in sinus rhythm. The VDDR mode continued to be an alternative in AVB.

In Spain, home follow-up or monitoring was not common in patients with pacemakers and the rate was somewhat over 50% in patients with CRT-D devices.

The current economic situation appears to influence the quality of the pacing carried out, especially in elderly patients and in CRT.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The authors would like to thank nurses Pilar Gómez Pérez and Brígida Martínez Noriega and Mr. Gonzalo Justes Toha, a specialist in information technology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, for their continued help in maintaining the registry and its analysis. We would also like to thank the health professionals and the pacemaker manufacturers located in Spain who cooperated by providing the data analyzed in this report.