This report describes Spanish cardiac pacing activity during 2019: quantities and types of devices and demographic and clinical factors.

MethodsThe analysis is based on data obtained from the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card, data submitted to the online platform cardiodispositivos.es, and supplier-reported data on the total number of implanted pacemakers.

ResultsInformation was received on 15 833 procedures from 102 implantation centers, representing 39% of the estimated total activity. The implantation rates of conventional and resynchronization pacemakers were 832 and 32 units per million population, respectively. A total of 431 leadless pacemakers were implanted. Most implantations were performed in elderly patients (mean age, 78.7 years). Most electrodes were bipolar and with active fixation and 34.1% were magnetic resonance imaging-compatible. Atrioventricular block was the most common electrocardiographic abnormality. Dual-chamber sequential pacing predominated; nonetheless, up to 20% of patients in sinus rhythm received a single-chamber ventricular pacemaker, mainly those older than 80 years of age and women. Remote monitoring capability was present in 41% of cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers and in 14.8% of conventional pacemakers.

ConclusionsConsumption of pacing generators increased by 1.6%, mainly due to a 15.1% increase in cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers. Sequential pacing predominates; its use is influenced by age and sex. Remote monitoring increased by 20.6% in cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers and continues to be scarce in conventional pacemakers.

Keywords

Since 1990, the Spanish National Pacemaker Data Bank has collected data on cardiac pacing activity in Spain and annually published this information in Revista Española de Cardiología as a report of the Spanish Pacemaker Registry.1–17 In the current document, the Cardiac Pacing Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology reports the activity corresponding to 2019 and compares the results with those of previous years and with those reported by our neighboring countries. The information recorded includes demographic characteristics, procedure and implanted device data, and data concerning the remote monitoring of devices.

METHODSThree sources of information were used to prepare the registry: the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC), the databases of the centers themselves, and the online CardioDispositivos.es platform,18 launched in January 2019 in collaboration with the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices to centralize and homogenize the information concerning pacemakers and defibrillators, as well as to optimize the monitoring of these health care products.

Despite the abovementioned sources, data have not been obtained on 100% of the activity performed and we thus use the information provided by the device suppliers to obtain the complete data on devices implanted. In addition, this information is checked against the data published by the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Association (Eucomed).19

Implantation rates were calculated based on the demographic data published by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics as of July 1, 2019.20

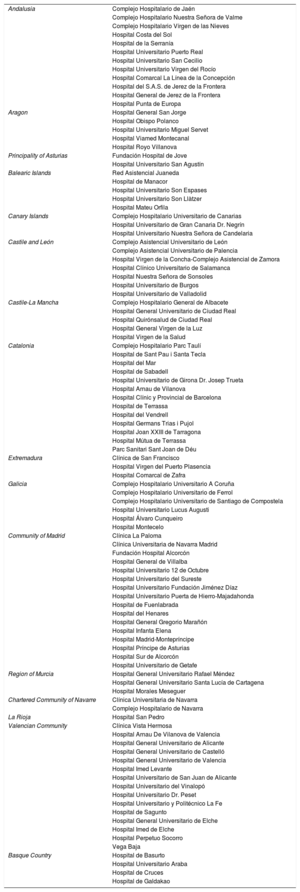

RESULTSSample qualityA total of 15 833 procedures were reported by 102 implant centers (table 1), corresponding to 15 791 generator implantation and 42 lead replacement procedures. This figure represents 39% of the cardiac pacing activity reported by the device suppliers. Of the datasheets generated, 4482 were obtained via the CardioDispositivos.es platform.18

Public and private hospitals submitting data to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2019, grouped by autonomous community

| Andalusia | Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén |

| Complejo Hospitalario Nuestra Señora de Valme | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Vírgen de las Nieves | |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | |

| Hospital de la Serranía | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerto Real | |

| Hospital Universitario San Cecilio | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | |

| Hospital Comarcal La Línea de la Concepción | |

| Hospital del S.A.S. de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital General de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital Punta de Europa | |

| Aragon | Hospital General San Jorge |

| Hospital Obispo Polanco | |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Hospital Viamed Montecanal | |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | |

| Principality of Asturias | Fundación Hospital de Jove |

| Hospital Universitario San Agustín | |

| Balearic Islands | Red Asistencial Juaneda |

| Hospital de Manacor | |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | |

| Hospital Universitario Son Llàtzer | |

| Hospital Mateu Orfila | |

| Canary Islands | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | |

| Castile and León | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León |

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Concha-Complejo Asistencial de Zamora | |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles | |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos | |

| Hospital Universitario de Valladolid | |

| Castile-La Mancha | Complejo Hospitalario General de Albacete |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud de Ciudad Real | |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| Catalonia | Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí |

| Hospital de Sant Pau i Santa Tecla | |

| Hospital del Mar | |

| Hospital de Sabadell | |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova | |

| Hospital Clínic y Provincial de Barcelona | |

| Hospital de Terrassa | |

| Hospital del Vendrell | |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol | |

| Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona | |

| Hospital Mútua de Terrassa | |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu | |

| Extremadura | Clínica de San Francisco |

| Hospital Virgen del Puerto Plasencia | |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | |

| Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela | |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro | |

| Hospital Montecelo | |

| Community of Madrid | Clínica La Paloma |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra Madrid | |

| Fundación Hospital Alcorcón | |

| Hospital General de Villalba | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | |

| Hospital Universitario del Sureste | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada | |

| Hospital del Henares | |

| Hospital General Gregorio Marañón | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Madrid-Montepríncipe | |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias | |

| Hospital Sur de Alcorcón | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital General Universitario Rafael Méndez |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena | |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | |

| La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro |

| Valencian Community | Clínica Vista Hermosa |

| Hospital Arnau De Vilanova de Valencia | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castelló | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia | |

| Hospital Imed Levante | |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante | |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó | |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset | |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | |

| Hospital de Sagunto | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | |

| Hospital Imed de Elche | |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro | |

| Vega Baja | |

| Basque Country | Hospital de Basurto |

| Hospital Universitario Araba | |

| Hospital de Cruces | |

| Hospital de Galdakao |

Given that the information included in the EPPICs and in the online platform were incomplete, various data were missing on each parameter analyzed, such as pacing mode (7.8%), lead position (8%), age (12.2%), sex (20.3%), lead polarity (19%), type of lead fixation (23.7%), preimplantation electrocardiogram (40.6%), symptoms (49%), etiology (65.5%), reason for generator explantation (70.1%), and reason for lead explantation (85.8%). The results reported in this document were based on the available data, excluding missing information.

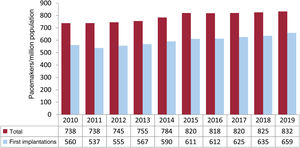

Numbers of conventional pacemakers implantedIn 2019, 39 181 conventional pacemaker devices were implanted in Spain according to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry. According to the National Institute of Statistics, the Spanish population was 47 100 396 inhabitants on July 1, 2019. Considering the total number of conventional pacemakers implanted, the implantation rate was 832 units/million population, slightly lower than that reported by Eucomed (837 units/million) (figure 1).

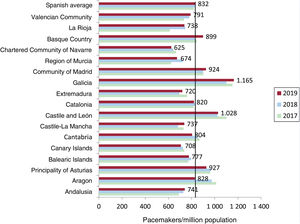

Regarding the distribution by autonomous community, Galicia and Castile and León topped the list with more than 1000 units/million population (1165 and 1028 units/million, respectively), followed by the Principality of Asturias and Community of Madrid (927 and 924 units/million, respectively). The Chartered Community of Navarre and Murcia had the lowest implantation rates, with 625 and 674 units/million population (figure 2).

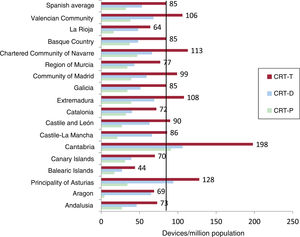

Cardiac resynchronization devicesAccording to data from the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, 1520 cardiac resynchronization therapy without defibrillation (CRT-P) devices and 2515 cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation (CRT-D) devices were implanted in Spain in 2019, giving 4035 total cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT-T) devices. The CRT-T rate was 85 units/million population, while that of CRT-Ps was 32 units/million, the same as that reported by Eucomed.

Cantabria was the autonomous community with the highest number of CRT-T implantations (198 units/million population), followed by the Principality of Asturias (128 units/million) and the Chartered Community of Navarre (113 units/million). The Balearic Islands was the community with the lowest number of CRT-T implantations, with 44 units/million population. Regarding CRT-Ps, Cantabria was once again top of the list with 91 units/million population, followed by the Chartered Community of Navarre with 47 units/million population and Madrid and Extremadura with 39 units/million population each. The communities with the fewest CRT-P implantations were La Rioja and Aragon, with 16 and 4 units/million population (figure 3).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy devices per million population in 2019, national average and by autonomous community. CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy without defibrillation; CRT-T, total cardiac resynchronization therapy.

The number of Micra (Medtronic, United States) model leadless pacemaker implantations increased again, with a total number of 431 units in 2019, a 15% increase vs 2018. Catalonia and Galicia continued to be the autonomous communities with the highest number of such implantations (116 and 80 units, respectively) and, together with the Community of Madrid, they encompassed 61% of all leadless pacemaker implantations performed in Spain. Five autonomous communities (Aragon, Cantabria, the Balearic Islands, Extremadura, and La Rioja) have still not implanted any leadless pacemakers. The proportion of leadless pacemakers implanted as a percentage of the total number of VVI/R devices continued to be very low (7.7%), although it has significantly increased vs 2018.

Demographic factorsThe average age of the patients receiving pacemakers was 78.7 years. It was somewhat higher for women than men (79.7 vs 77.9 years) and for replacements vs first implantations (81.0 vs 78.1 years). The age range 80 to 89 years old had the highest number of implants (42.9%), followed by 70 to 79 (31.03%), 90 to 99 (10.9%), 60 to 69 (10.1%), and 50 to 59 (3.2%); few implants were performed in patients younger than 40 years (< 1%). Just 0.2% of implanted patients were 100 years or older.

Symptoms and etiologyThe predominant reasons for pacemaker implantation were syncope and dizziness, with 40.8% and 24.2% of cases, respectively, followed by heart failure with 13.8%.

The most frequent cause continued to be conduction system fibrosis (83.5%), followed, at a much lower frequency, by ischemic etiology/acute myocardial infarction (4.2%), iatrogenic due to surgical complication (4%), ablation (1%), medication (0.2%), transcatheter aortic valve implantation (0.1%), valvular heart disease (2.9%), congenital heart disease (0.9%), carotid sinus syndrome (0.8%), dilated cardiomyopathy (1%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (0.3%), unspecified cardiomyopathy (0.8%), heart transplant (0.2%), and myocarditis (0.1%).

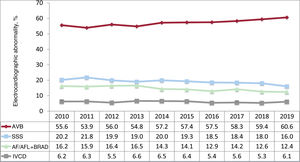

Preimplantation electrocardiogramAt 60.6%, atrioventricular block (AVB) was the most frequent preimplantation electrocardiographic abnormality. Third-degree AVB predominated (39.6%), followed by second-degree AVB (15.6%) and first-degree AVB (1.1%). Atrial fibrillation (AF) with complete heart block was seen in 6% of preimplantation electrocardiograms. Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) was the second most common abnormality, present in 28.4% of implantations, with bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome the most common type (5.9%), followed by SSS with bradycardia (5.1%), sinus arrhythmia/sinoatrial block (2.4%), and chronotropic incompetence (0.1%). The SSS subtype was unspecified in 2.5% of cases. Slow AF accounted for 12.4% of abnormal electrocardiographic findings. Bundle branch block was the indication in 6.1% of cases (figure 4).

Regarding differences according to sex, AVB (excluding blocked AF) was more common in men (56.1% vs 51.5%), whereas SSS (excluding slow AF) was more frequent in women (20.5% vs 13.8%). Bundle branch block was slightly more common in men (6.7% vs 5.2%). Slow AF and blocked AF constituted 19.2% of the indications in men and 16.2% of those in women.

First implantations and generator and/or lead replacementsOf generators implanted, 76.3% were first implantations and 22% were replacements. Generator and lead replacement represented 1.3% of activity while lead replacement alone comprised 0.4%.

The most frequent cause of generator replacement was once again end-of-life battery depletion (87.1%), followed by elective replacement (6.2%), infection (1.8%), pacemaker syndrome (1.5%), premature depletion (1.2%), dysfunction (1%), advisories (0.2%), and unspecified causes (< 1%).

The most frequent reason for lead replacement was infection/ulceration (58.3% of cases), followed by dysfunction (25%), displacement (11.1%), and advisories (5.6%).

Electrode typeActive-fixation leads were the most frequently used type of electrode (87.4%), in both the atrium (87.0%) and right ventricle (89.4%) and in patients > 80 years old (85.3%) and in younger patients (89.8%). Passive fixation predominated in coronary sinus leads (85.3%). Regarding polarity, most leads were bipolar (97.2%), in both the atrium (98.5%) and ventricle (98.6%), whereas tetrapolar leads were more common in the coronary sinus (73.4%) according to data collected through the CardioDispositivos.es platform18 (this variable is not considered in the EPPICs).

Magnetic resonance imaging-compatible leads represented 34.1% overall (23.9% of atrial leads and 37.6% of ventricular leads). In patients ≤ 80 years, 35.5% of implanted leads were magnetic resonance imaging-compatible vs 33.8% of those implanted in individuals > 80 years.

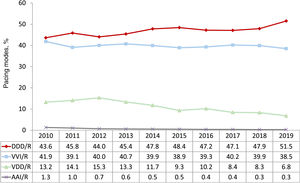

Pacing modesSequential dual-chamber pacing with either 1 or 2 leads continued to be the predominant pacing mode, used in 58.3% of all generators implanted, a similar number to that of the 2018 registry. The use of single-lead sequential pacing (VDD/R) fell slightly to 6.8%. The number of first implantations of VDD/R generators fell again to 4%, as well as the number of replacements, to 15.8%, after a slight increase in 2018. Dual-lead dual-chamber pacing (DDD/R) continued to be the most frequently used mode, with a slight increase vs the previous year to 51.5% of all generators implanted (54.5% of first implantations and 41.5% of replacements). In total, 98% of the dual-chamber devices were implanted with biosensors allowing modification of the pacing frequency (figure 5).

Single-chamber pacing represented just 38.8% of all generators implanted in 2019, a slight decrease vs the numbers recorded in 2018. This group included, at 0.3%, single-chamber atrial pacing (AAI/R), which is the same proportion as in previous years. Single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R) fell slightly to 38.5% (38.3% of first implantations and 38.9% of replacements). Taking into account the preimplantation electrocardiographic diagnosis, which indicated that only 18.6% of implantations were performed in patients with sustained atrial tachyarrhythmia, an estimated 20.2% of patients receiving single-chamber ventricular pacing were implanted with a pacemaker capable of maintaining atrioventricular (AV) synchrony.15,16 The various factors affecting the final pacing mode decision are analyzed in the following section (figure 5).

Pacing mode selectionAtrioventricular blockPatients with AVB and permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia (EPPIC code 8) have been excluded from this section to properly assess the degree of adherence to the most recommended pacing modes. Factors possibly influencing this selection were analyzed, such as patients’ age and sex and the degree of blockage.

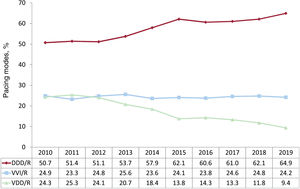

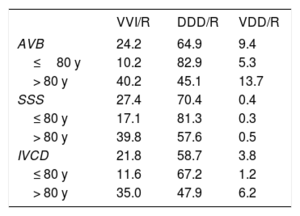

Atrial synchronous pacing (DDD/R and VDD/R modes) once again predominated (74.3%), with a proportion comparable to those of previous years. The use of VDD/R fell again to 9.4% due to an increase in DDD/R mode to 64.9%. VVI/R mode remained stable at 24.2% and biventricular pacing represented 1.3% (figure 6).

In patients aged ≤ 80 years, pacing maintaining atrioventricular (AV) synchrony clearly predominated (88.2%), with DDD/R mode the most widely used (82.9%). The use of VDD/R is rare in this age group (5.3%) and has markedly decreased vs 2018. Single-chamber pacing is uncommon in this age group (10.2%). In contrast, in patients older than 80 years, the use of devices maintaining AV synchrony continued to be much lower (58.8%), whereas single-chamber pacing was much more frequent, reaching 40.2%. Similarly, VDD/R mode was more frequently used in patients older than 80 years (13.7%), whereas DDD/R mode was less frequent (45.1%) (table 2).

Distribution (%) of pacing modes by electrocardiographic abnormality and age group in 2019

| VVI/R | DDD/R | VDD/R | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVB | 24.2 | 64.9 | 9.4 |

| ≤80 y | 10.2 | 82.9 | 5.3 |

| > 80 y | 40.2 | 45.1 | 13.7 |

| SSS | 27.4 | 70.4 | 0.4 |

| ≤ 80 y | 17.1 | 81.3 | 0.3 |

| > 80 y | 39.8 | 57.6 | 0.5 |

| IVCD | 21.8 | 58.7 | 3.8 |

| ≤ 80 y | 11.6 | 67.2 | 1.2 |

| > 80 y | 35.0 | 47.9 | 6.2 |

AVB, atrioventricular block; DDD/R, sequential pacing with 2 leads; IVCD, intraventricular conduction defect; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VDD/R, single-lead sequential pacing; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing.

Atrial-based pacing continued to be more commonly used in patients with first- and second-degree AVB (80.7%) and less so in patients with third-degree AVB (73.5%). However, these differences were minimal in patients ≤ 80 years of age (92.3% for first- and second-degree AVB vs 88.4% for third-degree AVB), whereas they were somewhat more pronounced in those older than 80 years of age (66.7% vs 56.9%).

Sex continued to be a major determinant of the pacing mode. DDD/R pacing was more frequently used in men (68.6% vs 59.2% in women), whereas VDD/R pacing was used slightly more commonly in women (12.1% vs 8.8%). In patients ≤ 80 years, there were no longer differences in the use of DDD/R pacing mode according to sex. In the group of patients older than 80 years, DDD/R mode was more commonly used in men (50.1% vs 41.3%), whereas VDD/R and VVI/R modes were more frequently used in women (16.9% vs 12.6% for VDD/R mode and 41.2% vs 35.9% for VVI/R mode). Once again, DDD/R and VVI/R were used at practically the same proportions in women older than 80 years of age (41.3% vs 41.2%).

The use was stable of single-chamber ventricular pacing in patients with electrocardiographic diagnosis of AVB with preserved sinus rhythm (24.2%). This figure was even higher in older patients (40.2% in those older than 80 years old) and higher for third-degree blocks and in women of both age bands.

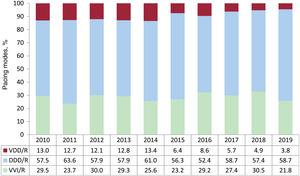

Intraventricular conduction defectsPacing maintaining AV synchrony continued to predominate (76.5% of implantations). Dual-chamber pacing in DDD/R mode accounted for 58.7% and continued to be the most common approach, with figures similar to those of previous years. VVI/R mode fell to 21.8% while VDD/R mode declined once again to 3.8%. The use of CRT-P devices in patients with an intraventricular conduction defect (IVCD) in sinus rhythm increased vs the previous year, reaching 14%. Biventricular pacing in patients with AF remained rare but increased vs previous years (1.7%) (figure 7).

Age continued to be a determinant of the pacing mode choice in patients with an IVCD. In those older than 80 years, VVI/R mode represented 35%, a marked decrease vs the previous year, whereas DDD/R mode continued to predominate, with stable figures of 47.9%. In patients ≤ 80 years, the use of VVI/R mode also fell to 11.6% due to greater use of DDD/R mode, which grew to 67.2%. VDD/R mode was still used in 6.2% of patients older than 80 years, whereas it was barely used in those ≤ 80 years (1.2%) (table 2).

The use of CRT-P devices markedly increased again vs the previous year, reaching 15.7%. This increase was recorded in both patients older than 80 years (10.8%) and in younger patients, reaching 20% of all implants.21

Sick sinus syndromeAs usual, patients with SSS were divided between those who theoretically are in permanent AF or atrial flutter and have bradycardia and those who, at least theoretically, are in sinus rhythm. The aim was to evaluate the adherence of the pacing modes to the current recommendations in the clinical practice guidelines.15,16

- 1.

Sick sinus syndrome in permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia. VVI/R mode continued to predominate in this group, with 92.4% of generators implanted. In addition, 6.1% of patients received a DDD/R generator and VDD/R devices once again represented 0.5%. The DDD/R mode indication in this context is presumably because sinus rhythm restoration is expected. The percentage of patients receiving a CRT-P device remained stable at 1.1%.

- 2.

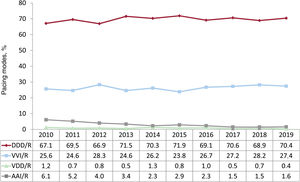

Sick sinus syndrome in sinus rhythm. DDD/R mode continued to be the most commonly used (70.4%), followed by VVI/R (27.4%), figures very similar to those of previous years (figure 8). AAI/R mode remained stable at 1.6%, whereas VDD/R mode fell to 0.4%; they remain rare pacing modes for SSS, in line with the recommendations of the latest clinical practice guidelines, published in 2013.22

By separately analyzing the different electrocardiographic manifestations of SSS, excluding EPPIC subgroups E7 and E8 (interatrial block and chronotropic incompetence) due to their rarity, the VVI/R pacing mode percentage can be seen to vary between 17.6% and 38.2%. Once again, the highest percentage of VVI/R devices corresponded to bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome. Nonetheless, these data may have been inflated by the erroneous inclusion of patients with slow-fast permanent AF episodes in this group and not in the already discussed E6 group.

In patients ≤ 80 years, the most frequently used pacing modes allowed atrial detection and pacing, that is, AAI/R and DDD/R, at 0.9% and 81.3%, respectively, vs only 17.1% for VVI/ R mode. This group showed a fall in the use of AAI/R mode due to DDD/R vs the figures for 2018. However, in the population older than 80 years of age, VVI/R mode was once again much more frequently used (39.8% vs 57.6% for DDD/R). This patient subgroup showed increase use of AAI/R mode in 2019, which almost doubled that of the previous year, with 1.7%. The use of VDD/R mode fell markedly in both age groups (0.3% and 0.5%). Age was found to influence the choice of pacing mode throughout the study period (table 2).

The data recorded for 2019 once again showed that sex also influences the choice of pacing mode. In the older population group (> 80 years old), VVI/R mode was used in 40.3% of women and in 35.3% of men. In those ≤ 80 years of age, VVI/R mode was used much less frequently and was slightly more common in women (14.7% for men vs 19.7% for women).

Remote monitoringIn 2019, 5808 conventional pacemakers were included in a remote monitoring program, as well as 624 CRT-Ps and 1809 CRT-Ds, representing 14.8%, 41%, and 71.9% of each device type, respectively.

DISCUSSIONThe sample obtained in the 2019 registry was larger than in previous years, with 3685 records more than in 2018, improving its representativeness and reliability. Nonetheless, this aspect shows room for improvement, and we at the Spanish Pacemaker Registry ask that implantation centers report their data via the online platform to increase the homogeneity and sample size, improve its quality, and permit the use of a single source of information. It is worth highlighting the difficulty encountered this year in the analysis and interpretation of the data because the information came from various sources.

In 2019, the number of conventional pacemakers implanted increased by 1.6%, maintaining the trend of the previous year. Nonetheless, the pacemaker rate (837/million population according to Eucomed) is still lower than the European average (963/million). As in previous years, the European rate is heavily impacted by countries with more than 1000 units/million population, such as Germany, Finland, and Italy.19 We do not know the causes of the variability in implantation rates among countries, although possible reasons include the different health system structures and management modalities found in our neighboring countries, as well as the social and demographic factors specific to each geographical area.

The CRT-T figure has increased by 11.6%, a notable increase given that its use increased by just 3.1% in 2018. This growth has mainly been due to CRT-P devices (15.1% vs 9.6% for CRT-D), which progressively represent a higher percentage of CRT-Ts, specifically 37.7% in 2019, with a CRT-D/CRT-P ratio of 1.6. Taking data from the European CRT survey, this ratio varies among European countries, with CRT-Ps reaching 88% of CRT-Ts in countries such as Bulgaria and close to 50% in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. The CRT-P rate obtained in the present registry and according to Eucomed was 32 units/million population, lower than the European average (59/million) and only higher than that of Poland and Greece, as in previous years. The recent publication of the results in Spain of the European Society of Cardiology survey on cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT Survey II) has shed light on the profile of CRT patients and revealed a lower proportion of patients older than 75 years and a higher proportion of patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, in functional class II, and with electrocardiogram-documented left bundle branch block in relation to other European countries, which probably indicates a better selection of candidates for this therapy.23

Leadless pacing maintained a modest growth rate (15% this year), similar to that of previous years. It was found in 7.7% of all single-chamber devices implanted, which indicates its continuing underuse, because the percentage of potential candidates for this pacing type is much higher. Strikingly, the number of autonomous communities that do not implant leadless pacemakers has increased to 5. The recent release on the market of new leadless pacemakers capable of atrial detection will allow the indications for this pacing mode to be extended to other patient groups, suggesting a possible increase in its use in the coming years.

Regarding preimplantation electrocardiography, AVB continues to be the most frequent disorder, with 60.6% of cases, followed by SSS with 28.4%. At the time of implantation, 18.4% of patients had AF.

In 2019, information could be provided on tetrapolar leads implanted in the coronary sinus, due to their inclusion in the platform, and they represented 73.4% of leads entered into this database, a figure similar to that reported in the European survey on CRT (CRT Survey II).23 In addition, the number of magnetic resonance-compatible leads increased to 34.1% (22.9% in 2018), in all age groups, with slightly higher values for the ventricle than the atrium (37.6% vs 23.9%). The importance of the extensive use of this type of material should be highlighted, given the increasingly frequent use of this imaging technique in elderly patients.

In AVB, the percentage of pacing with AV synchrony remained stable and continues to predominate (74.3%), whereas the use of VDD/R mode in this context is clearly falling (9.4%). In general, the use of VVI/R mode remained stable at 24.2% but once again reached 40.2% of all devices in patients older than 80 years. Similarly, pacing that maintains AV synchrony reached 88.2% in patients aged ≤ 80 years, whereas it represented just 58.8% in those over 80 years, which again confirms that age is a fundamental determinant of pacing mode. The lack of data on parameters such as cognitive level, frailty, dependence, and functional class has prevented a more detailed analysis of the possible causes of this discordance between the theoretically indicated pacing mode and that implanted. VDD mode continues to be much more common in patients older than 80 years (13.7%) than in those ≤ 80 years (5.3%).

The most notable finding in IVCDs is the fall in the use of VVI/R mode, which drops to 21.8%. DDD/R mode continues to predominate (58.7%). Biventricular pacing (CRT-P) increased again after declining in 2018, reaching 20% of all implants in the group of patients younger than 80 years.

In patients with SSS in permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia, the most frequently used mode is VVI/R, representing 92.4% of all devices implanted. In patients with SSS in sinus rhythm, DDD/R mode still predominates (70.4%). Age also influences the choice of pacing mode in this group of patients, with higher use of VVI/R mode in older patients (39.8%) than in those younger than 80 years (17.1%). AAI/R mode continues to be rare, in line with the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines and as a result of the findings of the DANPACE study, which showed a 0.6% to 1.9% rate of AVB development in patients with SSS.24 Clinical practice guidelines recommend DDD/R mode in SSS patients due to its ability to reduce the incidence of AF and strokes, as well as that of pacemaker syndrome.22

Notable findings in remote monitoring include the 20.6% increase in CRT-P monitoring (41% of CRT-P devices had remote monitoring capabilities). However, the percentage of pacemakers included in such programs continues to be insufficient, given their improved early detection of events, reduction in face-to-face visits, and cost-effectiveness.25 The need to optimize resource use at the organizational level involved and more limited evidence concerning the benefits of pacemakers vs implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and CRTs may be some of the reasons for their low implementation. Regarding the distribution of remote monitoring by autonomous community (excluding the data related to the Merlin system, due to unavailability), La Rioja, the Canary Islands, and the Basque Country stand out, with more than 50% of devices implanted included in remote monitoring programs, compared with communities with poor adherence, such as the Basque Country and Cantabria, with less than 10%. In the context of the current pandemic, and given the need for health care restructuring to reduce face-to-face visits, the Cardiac Pacing Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology champions remote monitoring as the principal follow-up method for patients with cardiac pacing devices.26

CONCLUSIONSThe number of pacemakers implanted increased in 2019 by 2.1%, largely due to growth in CRT-P devices (15.1%). The steady increase in leadless pacemakers continues, but huge variations are evident among autonomous communities. Sequential dual-chamber pacing predominates, and age and sex influence the choice of pacing mode. Notable findings include the low implementation of remote monitoring in the pacemaker population, the preferred follow-up approach in the current circumstances. In addition, increased use of the online platform CardioDispositivos.es is necessary to improve registry quality.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.