This document includes cardiac pacing activity performed in Spain in 2021: figures for implanted devices, demographic and clinical factors, characteristics of the implanted material, and remote monitoring data.

MethodsThe European Pacemaker Patient Card, the CardioDispositivos.es online platform, the centers’ own databases and the data provided by the supplier companies are used as sources of information.

Results17.360 procedures were registered from 95 hospitals, which represents 43% of the activity. The implantation rates of conventional and resynchronization pacemakers were 822 and 31 units per million population, respectively. 652 leadless pacemakers were implanted. The mean age of implantation is high (78.8 years), and atrioventricular block is the most frequent electrocardiographic abnormality. Dual-chamber pacing mode predominated, nonetheless single-chamber pacing was performed in 19% of patients in sinus rhythm, mainly in the elderly. 28.5% of implanted conventional pacemakers and 56,2% of low-energy resynchronization pacemakers were included in the remote monitoring program.

ConclusionsIn 2021 the number of conventional pacemakers increased by 8.3% and resynchronizers by 18.9%, despite the decrease in low-energy resynchronization, probably attributable to the development of physiological pacing. Leadless pacemakers increased by 25%. The expansion of remote monitoring continued, consolidating as a fundamental follow-up method.

Keywords

The report of the Spanish pacemaker registry, which describes cardiac pacing activity in Spain, has been published annually since 1997.1–7 The current report considers activity data corresponding to 2021, which includes total numbers of implants, adherence to remote monitoring programs, patients’ clinical profiles, and aspects related to the procedure and material implanted, as well as the trends over time in recent years. In addition, the implantation rates are compared with those of our neighboring countries, provided by Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Association).8

After the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which saw a drop in the number of devices implanted,7 activity has recovered to that of previous years and growth continues in the selection of remote monitoring as a pivotal means of follow-up, as described in the following pages.

METHODSData related to total numbers of implants, as well as their inclusion in remote monitoring programs, were obtained from the yearly information submitted by the device manufacturers.

Clinical and procedural data were obtained from various sources: the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC), the submission of local databases to the Spanish pacemaker registry, and the online platform CardioDispositivos.es.9 For the latter, procedures could be entered in 3 ways: direct submission by the implanting centers, by integration from software applications of the device manufacturers, and by database migration from implanting centers via their uploading to the platform, after their prior verification.

Population statistics were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics on April 26, 2022, and refer to the population of Spain as of July 1, 2021.10

RESULTSSample qualityIn 2021, 95 hospitals reported 17 360 procedures (table 1), 7940 via EPPICs, 935 via local databases sent to the Spanish pacemaker registry, and 8485 via CardioDipositivos.es (7287 directly entered by implanting centers and 1198 by an integration process from platforms or by the migration of local databases). The procedures reported represent 43% of the activity performed.

Public and private hospitals submitting data to the Spanish pacemaker registry in 2021, grouped by autonomous community

| Center | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | 1770 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén | 204 |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | 198 |

| Hospital de La Serranía | 20 |

| Hospital Santa Ana de Motril | 6 |

| Hospital Universitario San Cecilio | 212 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme | 303 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | 535 |

| Hospital del S.A.S. de Jerez de La Frontera | 140 |

| Hospital Punta de Europa | 104 |

| Hospital Virgen de La Victoria | 46 |

| Sanatorio Virgen del Mar | 2 |

| Aragon | 746 |

| Hospital General San Jorge | 137 |

| Hospital Obispo Polanco | 52 |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | 557 |

| Principality of Asturias | 206 |

| Fundación Hospital de Jove | 36 |

| Hospital Universitario San Agustín | 170 |

| Balearic Islands | 458 |

| Grupo Juaneda | 16 |

| Hospital de Manacor | 94 |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | 348 |

| Canary Islands | 980 |

| Clínica Santa Catalina | 10 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias | 194 |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | 389 |

| Hospital General de La Palma | 50 |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | 337 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 988 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo | 25 |

| Complejo Hospitalario General de Albacete | 376 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real | 138 |

| Hospital General Virgen de La Luz | 144 |

| Hospital Virgen de La Salud | 305 |

| Castile and León | 1512 |

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia | 131 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | 494 |

| Hospital de León | 371 |

| Hospital Río Hortega | 32 |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos | 280 |

| Hospital Virgen de La Concha | 204 |

| Catalonia | 3069 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí | 157 |

| Hospital de Tortosa Verge de La Cinta | 123 |

| Hospital del Mar | 198 |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge | 636 |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | 552 |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida | 310 |

| Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona | 262 |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | 343 |

| Hospital de Terrassa | 90 |

| Hospital del Mar | 9 |

| Hospital del Vendrell | 52 |

| Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona | 174 |

| Universitario Mútua de Terrassa | 103 |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu | 60 |

| Extremadura | 46 |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | 46 |

| Galicia | 1787 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña | 470 |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol | 143 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago | 182 |

| Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro | 471 |

| Hospital Lucus Augusti | 325 |

| Hospital Montecelo | 196 |

| Community of Madrid | 2057 |

| Clínica Universitaria de Navarra Madrid | 6 |

| Fundación Hospital Alcorcón | 128 |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | 294 |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | 280 |

| Hospital 12 de Octubre | 428 |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada | 13 |

| Hospital del Henares | 92 |

| Hospital General Gregorio Marañón | 456 |

| Hospital Madrid-Montepríncipe | 1 |

| Hospital Militar Central Gómez Ulla | 55 |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias | 129 |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | 175 |

| Region of Murcia | 851 |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena | 149 |

| Hospital General Santa María del Rosell (Santa Lucía) | 255 |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer | 183 |

| Hospital Rafael Méndez | 154 |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | 110 |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 414 |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | 89 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | 325 |

| La Rioja | 243 |

| Hospital San Pedro | 240 |

| Hospital Viamed Los Manzanos | 3 |

| Valencian Community | 1375 |

| Clínica Vista Hermosa | 16 |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia | 94 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | 194 |

| Hospital de Manises | 113 |

| Hospital Francesc de Borja | 14 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castelló | 269 |

| Hospital IMED Levante | 16 |

| Hospital IMED Valencia | 2 |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante | 118 |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó | 21 |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | 413 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | 25 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | 72 |

| Hospital IMED de Elche | 2 |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro | 6 |

| Basque Country | 858 |

| Hospital de Basurto | 69 |

| Hospital Universitario Araba | 282 |

| Hospital Universitario de Galdakao | 58 |

| Hospital de Cruces | 449 |

| Total | 17 360 |

Because both the EPPICs and the online platform forms are not always fully completed, some data were missing on all parameters analyzed: 9.2% on pacing mode, 17.6% on lead position, 10.1% on age, 16.6% on sex, 24.7% on type of lead fixation, 25.9% on lead polarity, 54.6% on the preimplantation electrocardiogram, 58.7% on symptoms, 70% on etiology, 72.6% on the reason for generator explantation, and 19.7% on the reason for lead explantation. The results reported here were based on the available data, after the exclusion of missing information.

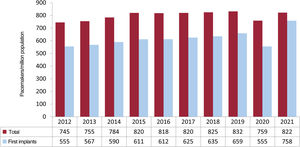

Numbers of conventional pacemakersIn 2021, 38 893 conventional pacemaker devices were implanted in Spain, according to Spanish pacemaker registry data. Considering the Spanish population of 47 326 687 individuals on July 1, 2021, the rate was 822 units/million population (U/M) (figure 1), which is slightly lower than the rate of 849 U/M reported by Eucomed.

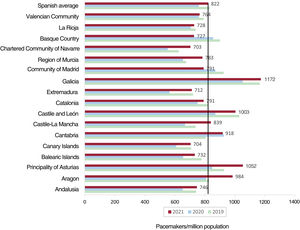

Regarding the distribution by autonomous community, Galicia, Principality of Asturias, and Castile and León stood out, with rates of 1172, 1052, and 1003 U/M, whereas Navarre and the Canary Islands were the communities with fewest implants, at 703 and 704 U/M (figure 2).

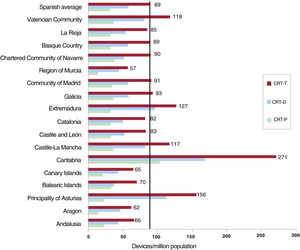

Cardiac resynchronization devicesRegarding cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), the number of total CRT (CRT-T) devices implanted in Spain in 2021 was 4194 units, comprising 1447 CRT without defibrillation (CRT-P) devices and 2747 CRT with defibrillation (CRT-D) devices, with rates of 89, 31, and 58 U/M, respectively. The CRT rates reported by Eucomed were similar: 32 U/M for CRT-P and 59 U/M for CRT-D.

By autonomous community, Cantabria stood out with a CRT-T rate of 271 U/M, followed at quite a distance by Principality of Asturias with 156 U/M and, at the bottom of the list, Region of Murcia with 57 U/M. For CRT-P devices, Cantabria also led the list, with 103 U/M, at some distance from the other communities, whereas Region of Murcia and Aragon showed the lowest rates, 14 and 15 U/M, respectively (figure 3).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy devices per million population in 2021, national average and by autonomous community. CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy without defibrillation; CRT-T, total cardiac resynchronization therapy.

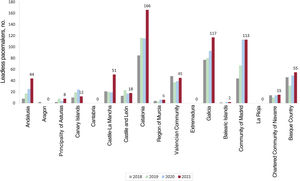

In 2021, the number of Micra (Medtronic, United States) leadless pacemakers increased to 652 units, of which 176 had the ability to maintain atrioventricular (AV) synchrony. The communities with the highest numbers of such implants were Catalonia, Galicia, and Madrid, with 166, 117, and 113, respectively. These 3 communities comprised 60% of these implants. Once again, Aragon, Cantabria, Extremadura, and La Rioja did not implant any device of this type in 2021 (figure 4).

Age and sexPacemaker implantation continued to be predominated by men (59.7% vs 40.3%), both for first implants (60.9% vs 39.1%) and replacements (56.3% vs 43.7%). Mean recipient age was 78.9 years, and it was slightly higher for replacements (80.6 years) than for first implants (78.4 years) and in women than in men (79.7 years vs 78.1 years). Just 1.2% of all devices were implanted in patients younger than 50 years, as well as 2.8% in those 50 to 59 years, 10.5% in those 60 to 69 years, 30.5% in those 70 to 79 years, 42.5% in those 80 to 89 years, 11.6% in those 90 to 99 years, and 0.3% in those older than 100 years.

Etiology and preimplantation symptomsConduction system fibrosis related to advanced age continued to be the most frequent cause of conduction disorders; it was linked to 84.2% of cases. Iatrogenic causes were the next most frequent: surgery (4%), transcatheter aortic valve implantation (1.7%), ablation (1%), and medication (0.1%). Ischemic causes followed (2.8%), as well as valvular heart disease (2.1%) and, to a lesser extent, carotid sinus syndrome (0.2%), vasovagal syncope (0.4%), congenital heart disease (0.7%), unspecified cardiomyopathy (0.6%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (0.7%), dilated cardiomyopathy (1.3%), endocarditis/myocarditis (0.1%), and heart transplant (0.1%).

The most frequent preimplantation symptom continued to be syncope (41.4%), followed by dizziness (24%) and, with much lower incidence, heart failure (15.3%) and asthenia (11.3%).

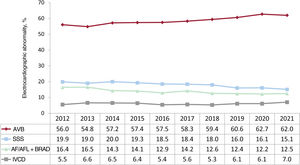

Preimplant ECGAV block (AVB) was, once more, the most frequent electrocardiographic abnormality, reported for 62% of implants. Regarding AVBs, complete AVB predominated, at 41.1%, followed by second-degree AVB (13.7%) and, at a much lower rate, first-degree AVB (1.2%). Atrial fibrillation (AF) with complete heart block accounted for 6% of implants. The second most common group of electrocardiographic abnormalities was sick sinus syndrome (SSS), at 27.6%, which included bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (5.5%), bradycardia/sinus pauses (5%), and sinoatrial block (1.9%). Chronotropic incompetence and interatrial block represented less than 1%. The SSS subtype was not specified in 2.3% of implants and 12.5% corresponded to slow AF. In addition, 7% of implants were performed due to an intraventricular conduction defect (IVCD) (figure 5).

Regarding the distribution by sex, AVB had a similar incidence in men and in women (54.7% vs 55.3%, excluding blocked AF), SSS was more prevalent in women (19.7% vs 12.5%), and IVCD was more frequent in men (9% vs 3.3%). Slow AF and blocked AF prompted 19.9% of implants in men and 16.2% of those in women.

Type of procedureOf all reported procedures (17 360), 13 095 were first implants (75.4%), 3896 were generator replacements (22.5%), 283 were generator and lead replacements (1.6%), and 86 were lead replacements alone (0.5%).

The most frequent reason for generator replacement was end-of-life battery depletion (69.5%), followed by elective replacement (22.5%) and, to a lesser extent, infection/erosion (2.5%), pacemaker syndrome (2.2%), lead complications/system changes (1.3%), premature depletion (0.8%), dysfunction (0.8%), and advisories (0.4%). In the case of lead replacement alone, the main reason was infection (41.5%), followed by dysfunction (22.6%), displacement (18.9%), perforation (5.7%), advisories (1.9%), and other unspecified causes (9.4%).

Electrode typeRegarding the type of fixation, 89.2% were active-fixation leads while 10.7% were passive-fixation, with slight differences by lead position: 89.4% active and 10.6% passive in the atrium and 91.1% active vs 8.9% passive in the right ventricle. In the left ventricle (tributary vein of the coronary sinus), 26.3% were active-fixation leads while 73.7% were passive-fixation. In terms of the distribution of fixation type by age, the use of active-fixation leads was slightly lower in patients > 80 years than in younger patients (86.3% vs 91.8%).

Bipolar leads predominated in both the right atrium and right ventricle (99.6% and 99.7%, respectively), whereas 32.2% of leads in the coronary sinus were bipolar, as well as 66.1% tetrapolar and 1.7% monopolar, according to CardioDispositivos.es data.9

Magnetic resonance imaging-compatible leads comprised 77.1%, with slightly lower rates in patients > 80 years than in younger patients (73.4% vs 79.5%) and in the right ventricle than in the right atrium (78.7% vs 84.9%). In the coronary sinus, 76.7% of leads were magnetic resonance imaging compatible. Regarding the generators implanted, 95.5% were compatible with this radiological technique. These data have been extracted from the CardioDispositivos.es platform, the most reliable source for this information.

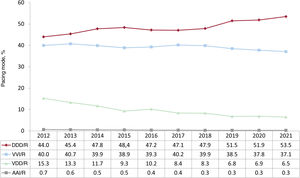

Pacing modesSequential dual-chamber DDD/R pacing was once again the most commonly used pacing mode in 2021 (53.5% of all procedures, 55.8% of first implants, and 46.11% of pacemaker replacements), in line with the upward trend of recent years. The use of VDD/R pacemakers has stabilized in the last 3 years,5–7 after several years with falls in their use; they represented 6.5% of procedures (4.2% of first implants and 13.6% of replacements).

Single-chamber ventricular pacing was used in 37.1% of all procedures, vs 37.8% in 2020. Single-chamber atrial pacing (AAI/R) continued to be negligible in Spain, with just 15 first implants (0.3%) (figure 6).

There was a decline in the use of biventricular CRT-P pacing, which represented 2.7% of all implants (2.4% with atrial leads vs 0.3% with biventricular pacing alone).

Regarding sex, differences remain in the pacing mode. Thus, compared with men, women received more single-chamber VVI or VVI/R pacing (37.5% vs 36% of procedures) and more VDD pacing (7.9% vs 6.1% of procedures reported) and less dual-chamber pacing DDD/R pacing (52.1% vs 54.6%).

The use of generators with a built-in activity sensor, which can increase heart rate when activated, was highly widespread. Such a sensor was used in 98.1% of dual-chamber DDD/R generators and 98.2% of single-chamber VVI/R generators.

Pacing mode selectionAtrioventricular blockThis section excludes patients with AVB and permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia (EPPIC code C8) to better assess the degree of adherence to the most recommended pacing modes in the clinical practice guidelines. Factors possibly influencing this selection were analyzed, such as patients’ age and sex and the type of block.

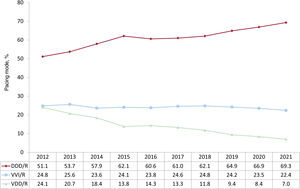

Pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony increased again, reaching 77.5% of cases, while DDD/R mode was used in 69.3% of implants and VDD/R mode in 7%. A notable finding is the negligible use of CRT-P therapy with atrial lead for this conduction disorder, at just 1.2% of implants (figure 7); an almost identical rate was obtained in 2020.

Age and sex continued to determine whether AV synchrony is maintained. Pacemakers capable of maintaining AV synchrony were used in 89% of individuals ≤ 80 years but in just 64.3% of individuals > 80, with an increase vs the previous year in this latter population group. VDD/R implantation stabilized at 3.9% of implants for AVB, particularly in patients > 80 years, in whom it was used in 12.1% (table 2). Regarding sex, the differences seen in previous years are slowly decreasing, although men were more likely to benefit from sequential pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony. Thus, 80.2% of men received this pacing mode, with DDD/R mode documented in 71.9% of EPPICs reported. In women, pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony was used in 75.5% of cases and VDD pacing was more common than in men (9.4% vs 6.9%). This apparent difference in pacing mode by sex was minimized when it was analyzed in conjunction with other factors such as age and is possibly overestimated due to the difference in reported procedures, because men ≤ 80 years represented a larger group. Thus, when these differences were analyzed by age, men ≤ 80 years used sequential AV pacing (DDD/R, VDD/R, or CRT-P with sequential AV pacing) in 89.6% of cases vs 88.3% in women. For those > 80 years, these pacing types were used in 66.9% of men vs 63.28% of women.

Distribution of pacing modes by electrocardiographic abnormality and age group in 2021

| Pacing mode | VVI/R, % | DDD/R, % | VDD/R, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVB, total | 22.5 | 69.3 | 7.0 |

| ≤ 80 y | 11.0 | 83.5 | 3.9 |

| > 80 y | 35.8 | 51.7 | 12.1 |

| SSS, total | 23.9 | 73.8 | 0.5 |

| ≤ 80 y | 15.1 | 82.2 | 0.5 |

| > 80 y | 35.9 | 62.2 | 0.7 |

| IVCD, total | 23.1 | 61.7 | 3.9 |

| ≤ 80 y | 12.8 | 73.5 | 1.6 |

| > 80 y | 36.9 | 45.9 | 6.8 |

AVB, atrioventricular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction defect; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

Regarding the pacing mode chosen by patients’ AVB degree, the data showed an increase in sequential dual-chamber pacing vs previous years, reaching 84% in patients with first- or second-degree AVB and 75.1% in patients with complete AVB. By age, this pacing mode is much less common in patients > 80 years, particularly in those with complete AVB, with rates of 61.5% in all cases or 64.1% in men and 61.4% in women. It was used in 12.1% of women and 11.1% of men in this age group and with this indication (complete AVB), which is considered more amenable to VDD pacing.

Single-chamber ventricular pacemaker implantation (VVI/R) for the treatment of AVB in patients with preserved sinus rhythm fell again and represented 22.5% of procedures. The use of this pacing mode continued to be considerable in patients > 80 years (35.8% of cases, a decrease vs the 39.5% of cases reported in 2020) (table 2).

Intraventricular conduction defectsWith this conduction disorder, whose cataloguing in the EPPIC is highly variable and which includes various causes of conduction disorders, from bundle branch conduction disorders to alternating bundle branch block, pacemaker implantation capable of maintaining AV synchrony continued to increase (76.9% of cases). This was largely due to DDD/R (61.7%), with a rate of 11.3% for triple-chamber CRT-P pacemakers. VDD and single-chamber VVI/R pacing fell again to 3.9% and 23.1% of cases, respectively.

The most commonly used mode continued to be DDD/R in both individuals ≤ 80 years (73.5%) and > 80 years (46%). A VVI/R pacemaker was implanted in 36.9% of patients > 80 years and in 12.8% of those ≤ 80 years. Pacing with VDD pacemakers slightly increased in 2021 and represented 3.8% of all pacemakers, 6.8% of devices implanted in patients > 80 years, and 1.6% of those implanted in individuals ≤ 80 years (table 2).

Regarding CRT-P devices, there was a decrease vs previous years, with 11.7% of all implants, 10.9% of those in patients > 80 years, and 12.1% of those in patients ≤ 80 years.

Sick sinus syndromeAs usual, patients with SSS were divided between those who theoretically are in permanent AF or atrial flutter and have bradycardia and those who are in sinus rhythm. In this way, the aim was to evaluate the adherence of the stimulation modes to the current recommendations in the clinical practice guidelines.11,12

- 1.

Sick sinus syndrome in permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia. VVI/R pacing predominated and was used in 90.3% of all implants. A system capable of maintaining AV synchrony was used in 9.7% of implants, mainly DDD/R (7.9% of cases). It is assumed that the use of this pacing mode is because an at least partial return to sinus rhythm was expected in many of the patients

- 2.

Sick sinus syndrome in sinus rhythm. Adherence to clinical practice guideline recommendations is gradually improving, with increases in pacing modes permitting atrial pacing and AV synchrony maintenance.11,12 Accordingly, DDD/R pacemakers were implanted in 73.8% of cases and VVI/R in 23.9%. The low uptake is notable of AAI/R pacing in the data submitted, with only 12 patients (slightly more than 1% of the total with this indication), and the other pacing modes—biventricular and VDD/R—were rarely used.

The electrocardiographic manifestation is key when the device is being chosen in SSS patients. Thus, subgroup E2 of the EPPIC (bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome) is the most frequently reported subgroup and the reason for more than 36% of implants due to sinus dysfunction. VVI/R pacemaker implantation may be inflated by the erroneous inclusion of patients with AF or permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia in this subgroup. Moreover, 52% of single-chamber pacemakers implanted in SSS were indicated for bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome.

Analysis of the SSS data from patients in sinus rhythm by age and sex revealed the existence of differences in the devices used, with greater use of dual-chamber pacing in younger patients and men. In patients ≤ 80 years, DDD/R pacing comprised 82.2%, VVI/R comprised 15.1%, and AAI/R just 1%. In contrast, in patients > 80 years, VVI/R pacing represented 35.9% of cases, although 53.9% of these had bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (table 2). Women more commonly received single-chamber VVI/R pacing than men (27.5% vs 19.7%). This difference was minimal in patients < 80 years but was accentuated in older patients, in whom it represented 40.4% of implants in women and 28.8% in men.

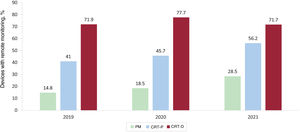

Remote monitoringIn 2021, 11 260 conventional pacemakers were included in a remote monitoring program, as well as 813 CRT-Ps and 1969 CRT-Ds, representing 28.5%, 56.2%, and 71.7% of the total of each device type (figure 8). By autonomous community, La Rioja, the Basque Country, and Navarre stood out with 78.8%, 77.8%, and 77.5% of devices included; in Extremadura, Asturias, and La Rioja, 97%, 95.5%, and 90% of CRT-P devices were included in this follow-up system, whereas 100% and 99% of CRT-D devices were included in La Rioja and the Canary Islands. These data refer to the monitoring of devices implanted in 2021, not those implanted in previous years.

DISCUSSIONIn 2021, 17 360 procedures were recorded in the Spanish pacemaker registry, which represented 43% of the activity reported by manufacturers, a slight increase vs 2020 (39% of the activity).7 Regarding the source of the data, the contribution of EPPIC data was similar to that of 2020 but the number of procedures reported via local databases increased by 42% while that submitted using CardioDispositivos.es9 increased by 40.5%, although the number is still low if we consider the total number of devices implanted. The objective of the Spanish pacemaker registry is to increase the sample size, mainly via the number of procedures submitted via the platform, which would undoubtedly augment the quality and reliability of the data, facilitate their analysis and interpretation by centralizing the information in a single source, and permit achievement of one of the main objectives of the platform: to be a warning system for implanted devices. This must be our area for improvement.

In 2021, the number of conventional pacemakers increased by 8.3%, reaching an implantation rate of 822 U/M. This number is similar to that of the prepandemic years,1–6 after a year (2020) with an overall drop in the number of implanted devices.13 The numbers reported by Eucomed are somewhat smaller (849 U/M) and Spain continues to have an implantation rate far below the European average (966 U/M). Regarding the activity of our neighboring countries, Hungary and Ireland are at the bottom of the list, with 583 and 694 U/M, although we must also highlight the low implantation rate in countries with high per capita incomes such as the United Kingdom and Netherlands (710 and 764 U/M). Germany, Italy, and Finland continue to head the list, with implantation rates exceeding 1000 U/M.8 In general, the published data corroborate those reported in Spain by Salgado et al.,13 with a major drop in the number of implants in 2020 and a recovery in 2021 to previous numbers, despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic during the entirety of 2021.14 In terms of the distribution by autonomous community, Galicia, Principality of Asturias, and Castile and León continued to stand out, probably due to their older populations.

The number of CRT-T generators increased by 8.9%, due to a 16% jump in the numbers of CRT-D devices. CRT-P devices fell by 1.1% vs 2020, breaking the upward trend of the years prior to the pandemic. The CRT-P rate is much lower than the European average (66 U/M), which has not shown this decrease; only 2 countries have lower implantation rates (Poland and Greece, with 29 and 12 U/M, respectively). The emergence in our laboratories of conduction system pacing has likely been the cause of this decrease because, although the current clinical practice guidelines assign a IIa level of recommendation to His bundle pacing after unsuccessful coronary sinus lead implantation,12 physiological pacing is replacing conventional CRT in many Spanish laboratories in patients with a cardiac resynchronization indication. Observational studies have shown promising results for His bundle pacing and that of the left bundle branch vs conventional CRT in terms of clinical improvement and ventricular remodeling and function, which will have to be validated in randomized clinical trials.15 The Physiological Pacing Registry of the Heart Rhythm Association16 will soon allow determination of the current situation in Spain for this pacing mode and its place in overall cardiac pacing activity.

The number of leadless pacemakers implanted increased by 25% vs 2020 and by 74% vs 2018. In particular, leadless pacemakers capable of maintaining AV synchrony represented 27% of all devices and are being used in a broader profile of candidates. Considerable heterogeneity persists in their distribution by autonomous community, with Galicia, Catalonia, and Madrid representing 60% of such implants. The higher cost of these devices vs conventional intravenous pacemakers is probably the main factor limiting their use. Boveda et al.17 have recently published a survey from the European Heart Rhythm Association that reports the factors determining the implantation of leadless pacemakers in tertiary European centers with availability of these devices in daily clinical practice. Advanced age, previous infection, or high risk of infection, as well as potential risk of lead complications, are the factors favoring the use of leadless pacemakers, which represent less than one-third of single-chamber pacemakers implanted in Europe.

Regarding the characteristics of the material implanted, bipolar leads predominated in the right atrium and ventricle (99%) and quadripolar leads, which enable the programming of distinct electronic configurations, stood out in the coronary sinus (67.5%). Most leads and generators were magnetic resonance-compatible (77% and 95%, respectively), according to data extracted from the CardioDispositivos.es platform,9 a crucial factor given the ever increasing use of this radiological diagnostic technique.

Regarding pacing modes, AVB maintained the slow but gradual trend seen in recent years for pacing maintaining AV synchrony, which was available in 77.5% of devices vs 76.5% in 2020; DDD/R mode predominated (69.3% of procedures). In patients > 80 years, single-chamber VVI/R pacing was the most widespread mode, with abandonment of sensing and atrial pacing in up to 35.8% of cases. This result confirms that age is one of the main factors determining the selection of pacing mode, although there was still a 4% decrease vs 2020. Other parameters such as frailty, the presence of paroxysmal AF, and cognitive decline possibly explain the selection of this pacing mode, which avoids the atrium and does not adhere to clinical practice guideline recommendations because, although increased mortality has not been linked to single-chamber pacing vs dual-chamber pacing in AVB, it has been associated with decreased functional class and the onset of AF or pacemaker syndrome.18 VDD/R pacing in individuals > 80 years and with indication for AVB continued to be relevant; this pacing mode was chosen for 12.8% of patients. Nonetheless, and although there was no decrease in the use of VDD/R in absolute terms, the coming years will see an even greater decrease in this pacing mode, because more VDD/R replacements than first implants were performed in 2021 (51% vs 49%).

In patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia (mainly AF or atrial flutter), as would be expected, single-chamber VVI/R devices continued to dominate; they were used in 90% of cases. In patients with SSS with atrial arrhythmias, the use of pacemakers capable of stimulating the atrium increased again, and the conventional DDD/R mode was used in 73.8% of patients. The limited implementation of AAI/R pacing continued, with very low levels in Spain (slightly more than 1% of interventions). As mentioned above, 36% of patients with this indication had bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (E2 of the EPPIC), which may help to explain the high percentage of single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R). In the remaining patients, the guidelines recommend DDD/R mode in SSS because of its ability to reduce the incidences of AF, strokes, and pacemaker syndrome.

The inclusion of devices in remote monitoring programs continued the upward trend begun with the pandemic,19 with a more striking increase in conventional pacemakers (14% of devices included in such programs in 2019 vs 28.5% in 2021) and CRT-P devices (41% vs 56%) than in CRT-D devices; the latter have shown inclusion percentages of about 70% to 77% in the last 3 years.4–6 The amply demonstrated safety and efficacy of this type of follow-up20 will surely lead to its continued growth in the coming years. This approach is also supported by the current clinical practice guidelines, in which it has acquired a high level of recommendation, particularly for patients who struggle to attend their health center, for advisories, and for reducing in-person visits.12

CONCLUSIONSAfter the first year of the pandemic, which showed an overall fall in procedures, implantation activity increased by about 8% for conventional pacemakers and by 9% for CRT-T devices. CRT-P activity decreased, probably due to the arrival of physiological pacing. The increase in leadless pacemakers continued, but large differences were seen among the autonomous communities. Remote monitoring consolidated its position as an essential means of follow-up. The numbers of procedures submitted via CardioDispositivos.es9 must be increased to improve the quality and reliability of the Spanish pacemaker registry data.

FUNDINGFor the maintenance and collection of the data included in the present registry, the Spanish Society of Cardiology has been supported by a grant from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS), the proprietor of these data.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSJ. Chimeno drafted the section on pacing modes; Ó. Cano reported the information related to the conventional pacemaker and CRT data; V. Bertomeu prepared the data on remote monitoring; and M. Pombo conducted the statistical analysis of leadless pacemakers and demographic and clinical data and coordinated the work.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.