This article reports the cardiac pacing activity performed in 2022, including the total number of implants, adherence to remote monitoring, demographic and clinical factors, and the characteristics of the implanted devices.

MethodsThe information sources were the CardioDispositivos online platform, the European pacemaker patient identification card, and data provided by the manufacturers.

ResultsThe rates of conventional pacemakers and low-energy resynchronizers were 866 and 34 units per million population, respectively. A total of 815 leadless pacemakers were implanted. In all, 16426 procedures performed in 82 hospitals were reported (9407 through CardioDispositivos), representing 40% of the activity. The mean age was 78.6 years, with a predominance of men (60.3%). The most frequent disorder was atrioventricular block, and 14.5% of the patients had atrial fibrillation. There was a predominance of the DDD/R pacing mode (55.6%), and pacing mode was influenced by age, such that more than one-third of patients older than 80 years in sinus rhythm received single-chamber ventricular pacing. The remote monitoring program included 35% of conventional pacemakers and 55% of low-energy resynchronization pacemakers.

ConclusionsThe number of conventional pacemakers increased by 5.6%, low-energy resynchronizers by 16%, and leadless pacemakers by 25%. Adherence to remote monitoring was stable. The number of procedures included in CardioDispositivos increased by 11%, although the sample volume decreased. In the coming years, the widespread use of the platform will likely lead to a high-quality registry.

Keywords

The present report describes cardiac pacing activity in Spain for 2022 and includes numbers of implants, demographic and clinical data, and the characteristics of the material implanted. In addition, we compare the data with those of previous years1–7 and those of our neighboring countries that have reported their activity to Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Association).8 This report also includes data on the degree of implementation of remote monitoring as a means of follow-up of implanted patients.

METHODSImplantation rates in Spain, both at the national and autonomous community levels, as well as remote monitoring data, were obtained from the information provided by device manufacturers.

Demographic and clinical data and the characteristics of the material implanted were obtained from 3 sources: first, from the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC), which was submitted by the implanting centers; second, from local databases, sent to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry; third, from the online platform CardioDispositivos.9 This platform, which is owned by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) and is managed by the Spanish Society of Cardiology, houses procedural data obtained in 3 ways: a) by direct submission by implanting centers, b) integration from software applications of the device manufacturers, and c) by database migration from implanting centers via their uploading to the platform, after their prior verification.

The population data for Spain on January 1, 2022, obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics on May 2, 2023, were used to calculate rates.10

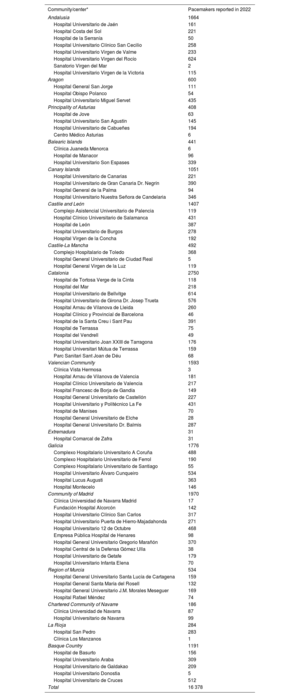

RESULTSSample qualityIn 2022, 82 hospitals reported 16 426 procedures, 7019 via EPPICs and 9407 via the online platform CardioDispositivos9 (table 1). Of the latter, 7436 were directly submitted by the implanting centers and 1971 by a migration or integration process from other platforms or databases. Specifically, 40 hospitals participated using EPPICs and 45 via CardioDispositivos (the total number of participating hospitals was 82 because 3 hospitals used both methods to provide data). The procedures reported represented 40% of the activity performed.

Public and private hospitals submitting data to the Spanish pacemaker registry in 2022, grouped by autonomous community

| Community/center* | Pacemakers reported in 2022 |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | 1664 |

| Hospital Universitario de Jaén | 161 |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | 221 |

| Hospital de la Serranía | 50 |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio | 258 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme | 233 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | 624 |

| Sanatorio Virgen del Mar | 2 |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | 115 |

| Aragon | 600 |

| Hospital General San Jorge | 111 |

| Hospital Obispo Polanco | 54 |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | 435 |

| Principality of Asturias | 408 |

| Hospital de Jove | 63 |

| Hospital Universitario San Agustín | 145 |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes | 194 |

| Centro Médico Asturias | 6 |

| Balearic Islands | 441 |

| Clínica Juaneda Menorca | 6 |

| Hospital de Manacor | 96 |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | 339 |

| Canary Islands | 1051 |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | 221 |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | 390 |

| Hospital General de la Palma | 94 |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | 346 |

| Castile and León | 1407 |

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia | 119 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | 431 |

| Hospital de León | 387 |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos | 278 |

| Hospital Virgen de la Concha | 192 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 492 |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo | 368 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real | 5 |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz | 119 |

| Catalonia | 2750 |

| Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta | 118 |

| Hospital del Mar | 218 |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge | 614 |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | 576 |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida | 260 |

| Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona | 46 |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | 391 |

| Hospital de Terrassa | 75 |

| Hospital del Vendrell | 49 |

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII de Tarragona | 176 |

| Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa | 159 |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu | 68 |

| Valencian Community | 1593 |

| Clínica Vista Hermosa | 3 |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia | 181 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | 217 |

| Hospital Francesc de Borja de Gandía | 149 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castellón | 227 |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | 431 |

| Hospital de Manises | 70 |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | 28 |

| Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis | 287 |

| Extremadura | 31 |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | 31 |

| Galicia | 1776 |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña | 488 |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol | 190 |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago | 55 |

| Hospital Universitario Álvaro Cunqueiro | 534 |

| Hospital Lucus Augusti | 363 |

| Hospital Montecelo | 146 |

| Community of Madrid | 1970 |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra Madrid | 17 |

| Fundación Hospital Alcorcón | 142 |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos | 317 |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | 271 |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | 468 |

| Empresa Pública Hospital de Henares | 98 |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | 370 |

| Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla | 38 |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | 179 |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena | 70 |

| Region of Murcia | 534 |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena | 159 |

| Hospital General Santa María del Rosell | 132 |

| Hospital General Universitario J.M. Morales Meseguer | 169 |

| Hospital Rafael Méndez | 74 |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 186 |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | 87 |

| Hospital Universitario de Navarra | 99 |

| La Rioja | 284 |

| Hospital San Pedro | 283 |

| Clínica Los Manzanos | 1 |

| Basque Country | 1191 |

| Hospital de Basurto | 156 |

| Hospital Universitario Araba | 309 |

| Hospital Universitario de Galdakao | 209 |

| Hospital Universitario Donostia | 5 |

| Hospital Universitario de Cruces | 512 |

| Total | 16 378 |

Given that the EPPICs were sometimes incomplete, some data were missing for each variable. Calculations were performed after the exclusion of these missing data, which comprised 8.5% for age, 12.5% for sex, 59.4% for symptoms, 72.9% for etiology, 58.2% for preimplant electrocardiogram, 23.5%, 21.2%, 12.8%, and 21.5% for lead position, fixation, magnetic resonance (MR) compatibility, and polarity, 9.5% for reason for lead explantation, and 93.8% for reason for generator explantation.

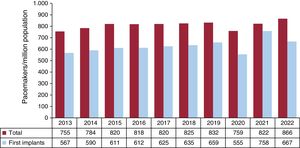

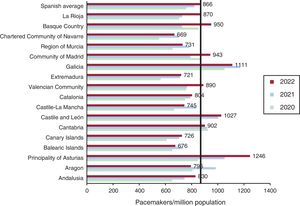

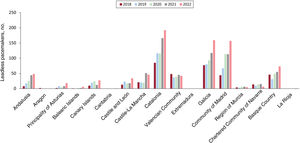

Conventional pacemakersThe total number of conventional pacemakers implanted in Spain in 2022 was 41 082. Because the Spanish population on January 1, 2022, comprised 47 432 893 individuals (24 195 741 women and 23 237 152 men), the implantation rate was 866 units/million population (figure 1). The autonomous communities with the highest rates were Asturias, Galicia, and Castile and León, all with more than 1000 units/million population (1111, 1246, and 1027 units/million, respectively). Navarre had the lowest implantation rate, at 669 units/million population (figure 2).

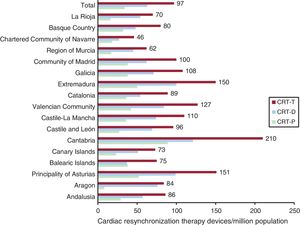

According to Spanish Pacemaker Registry data, 4604 cardiac resynchronization therapy generators (CRT-Ts) were implanted in 2022, comprising 2992 CRT with defibrillation (CRT-D) devices and 1612 CRT without defibrillation (CRT-P) devices. Considering the Spanish population on January 1, 2022, the CRT-T, CRT-D, and CRT-P rates were 97, 63, and 34 units/million population, respectively (figure 3).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy devices per million population in 2022, national average and by autonomous community. CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy without defibrillation; CRT-T, total cardiac resynchronization therapy.

By autonomous community, Cantabria, Asturias, and Extremadura stood out with CRT-T rates of 210, 151, and 150 units/million; Navarre was at the bottom of the list, at 46 units/million. For CRT-P devices, Cantabria also headed the list with 89 units/million population, followed at some distance by Asturias and Extremadura, at 52 and 50 units/million, respectively. Aragon had the lowest number of CRT-P implants, at 8 units/million population (figure 3).

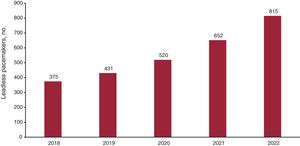

Leadless pacemakersIn 2022, 815 leadless pacemakers were implanted in Spain (figure 4), 226 with the ability to maintain atrioventricular (AV) synchrony. Catalonia had the highest number of such implants (n=192), followed by Galicia and Madrid (159 and 157 units). Notably, Aragon and Extremadura did not implant any device of this type (figure 5).

Demographic and clinical dataThe average patient age at implantation was 78.6 years. Mean age was somewhat older for women than men (79.6 vs 77.9 years) and for replacements vs first implants (79.9 vs 78.4 years). The distribution by decade was as follows: < 50 years, 1.9%; 50 to 59 years, 3%; 60 to 69 years, 10.4%; 70 to 79 years, 31.4%; 80 to 89 years, 41.9%; 90 to 99 years, 11.1%; and > 99 years, 0.3%.

Men predominated in pacemaker implantation (60.3% vs 39.7%), both for first implants (61.2% vs 38.8%) and replacements (57.2% vs 42.8%).

The main reason for pacemaker implantation was syncope (41.6%), followed by dizziness (23.4%) and heart failure (15.9%). Less common reasons were prophylactic implantation (8.4%) and asthenia (5%).

The most common cause of conduction disorders was conduction system fibrosis related to advanced age (80.6%), followed by iatrogenic causes (4.5%, surgery; 2.5%, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; 1.1%, ablation), ischemic causes (4%), vasovagal syncope (0.2%), valvular heart disease (3.2%), congenital heart disease (0.6%), dilated cardiomyopathy (1.5%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (0.7%), unspecified cardiomyopathy (0.7%), carotid sinus syndrome (0.2%), endocarditis/myocarditis (0.1%), and heart transplant (0.1%).

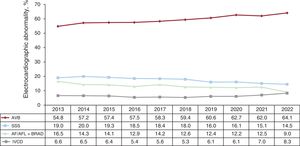

The most frequent preimplantation electrocardiographic abnormality was atrioventricular block (AVB) (58.6%); of these, third-degree AVB predominated, at 41% of procedures, followed by second-degree AVB, at 15.9%. Atrial fibrillation (AF) with complete heart block was reported for 5.5% of implants. Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) represented 23.5%, with the following distribution: sinus bradycardia/pauses (5.6%), bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (4.9%), sinoatrial block (1.8%), chronotropic incompetence (0.4%), and unspecified SSS (1.8%). Slow AF accounted for 9% of abnormal ECG findings. Intraventricular conduction defect (IVCD) was reported for 8.3% of cases (figure 6).

Regarding the distribution of electrocardiographic abnormalities by sex, AVB had a similar incidence in men and women (57.9% vs 57%), whereas SSS was more frequent in women (19.5% vs 11.6%) and IVCD was more prevalent in men (9.2% vs 6.4%). Slow or blocked AF prompted 15.3% of implants in men and 12.6% of those in women.

Type of procedureOf the 16 426 reported procedures, 12 610 were first implants (76.8%), 3525 were generator replacements (21.4%), 243 were generator and lead replacements (1.5%), and 48 were lead replacements alone (0.3%).

The most frequent reason for generator replacement was end-of-life battery depletion (93.2%), followed by elective replacement (4.3%), pacemaker syndrome (0.4%), and lead complications/system changes (0.8%). Infections were responsible for 1.3% of generator replacements. In the case of lead explantation, 52.4% were due to infection, 35.7% to displacement, and 2.4% to dysfunction.

Electrode typeRegarding lead position, 36.7% were in the right atrium (RA), 61.5% in the right ventricle (RV), and 1.7% in the coronary sinus; 0.1% were epicardial leads. Of the leads implanted in the RV, no location was specified for 62.3%. The reported locations were as follows: 55.1% in the RV apex, 27.8% in the septum/RV outflow tract, and 17.1% in the conduction system (bundle of His, left branch, deep septum).

Overall, 91.1% of leads had active fixation while 8.9% had passive fixation, with no significant differences among the different positions (93% in the RA and 91.6% in the RV). In the tributary veins of the coronary sinus, 55% of the leads had active fixation. The percentage of active-fixation leads was slightly lower in patients older than 80 years than in the younger population (86.7% vs 93.8%).

In addition, 99.7% of leads were bipolar in both the RA and RV. In the coronary sinus, 58.4% were quadripolar, 40.7% were bipolar, and 0.9% were monopolar, according to CardioDispositivos platform data.9

Of the leads reported to the CardioDispositivos platform,9 98.1% were MR compatible; this percentage was slightly higher in patients ≤ 80 years (99.1%) than in those older than 80 (96.6%). Finally, 95.2% of generators were compatible with this radiological technique.

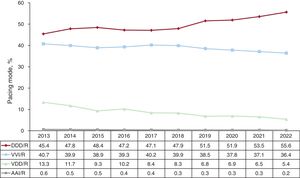

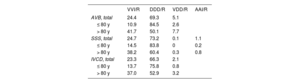

Pacing modesSequential dual-chamber DDD/R pacing continued the tendency of previous years with continuous proportional growth.5–7 This form of pacing represented 55.6% of all procedures, 57.1% of first implants, and 50.9% of generator replacements. VDD/R pacing was used in 5.4% of all pacemakers and in 11.2% of generator replacements. Single-chamber ventricular pacing was used in 36.4% of all procedures, vs 37.1% in 2021. Single-chamber atrial pacing (AAI/R) was once again rare, with just 25 interventions between first implants and replacements, 0.2% of the total (figure 7).

Differences by sex were evident in pacing mode. Thus, 61.5% of women vs 65.2% of men, received pacing modes capable of maintaining AV synchrony in 2022. This pacing was DDD/R in 53.1% of women and in 57.4% of men.

The use of generators with a built-in activity sensor, which can increase heart rate when activated, was highly widespread: they were used in more than 99% of interventions.

Pacing mode selectionAtrioventricular blockThis section excludes patients with AVB and permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia (EPPIC code C8) to better assess the degree of adherence to the most recommended pacing modes in the clinical practice guidelines.11,12 Factors possibly influencing this selection were analyzed, such as patients’ age and sex and the type of block.

Pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony fell slightly vs 2021, dropping from 77.5% to 75.5% of procedures; DDD/R mode was used in 69.3% of implants and VDD/R mode in 5.1%. A notable finding was the negligible use of CRT-P therapy with atrial lead for this conduction disorder, at just 1.2% of implants, an identical rate to that of 2021.7

Age and sex determined whether the pacing mode maintained AV synchrony. AV synchrony was maintained in 89.1% of patients younger than 80 years vs 57.7% of older patients, and a drop from 2021 was detected in this last population group, in which it was used in 64.3%. This decrease was largely due to a fall in the implantation of VDD/R devices, which were used in 5.1% of patients with AVB and in 2.6% of patients ≤ 80 years, vs 7.7% of patients with AVB and older than 80 years (table 2).

Distribution of pacing modes (%) by electrocardiographic abnormality and age group in 2022

| VVI/R | DDD/R | VDD/R | AAI/R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVB, total | 24.4 | 69.3 | 5.1 | |

| ≤ 80 y | 10.9 | 84.5 | 2.6 | |

| > 80 y | 41.7 | 50.1 | 7.7 | |

| SSS, total | 24.7 | 73.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| ≤ 80 y | 14.5 | 83.8 | 0 | 0.2 |

| > 80 y | 38.2 | 60.4 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| IVCD, total | 23.3 | 66.3 | 2.1 | |

| ≤ 80 y | 13.7 | 75.8 | 0.8 | |

| > 80 y | 37.0 | 52.9 | 3.2 |

AVB, atrioventricular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction defect; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

Regarding sex, differences were maintained between the type of pacing received by women and men for AVB with the absence of permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia. Single-chamber VVI/R pacing was used in 20.4% of procedures in men vs 30.8% for women. DDD/R mode was implanted in 74.8% of men and in 62.2% of women. VDD/R pacemakers were more commonly used in women with this indication (5.9% vs 4.7%). These differences between the sexes were greater in individuals older than 80 years. Accordingly, DDD/R pacing was used in 57.2% of men older than 80 years and in 45.1% of women of the same age group.

Regarding the pacing mode chosen by patients’ AVB degree, sequential dual-chamber pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony was used in 80.2% of patients with first- or second-degree AVB and in 73.4% of patients with complete AVB. By age, this pacing mode was much less common in patients > 80 years, particularly in those with complete AVB, in whom it was used in 66.1% of all cases. The most frequent use for VDD pacing was in patients with first- or second-degree AVB and older than 80 years: it represented 9.5% of all implants, 12.5% of those in women, and 8.3% of those in men.

Single-chamber ventricular pacemaker implantation (VVI/R) for the treatment of AVB in patients with preserved sinus rhythm slightly increased and represented 24.4% of procedures. The use of this pacing mode continued to be considerable in patients older than 80 years (41.7% of cases, higher than the 35.8% of cases in 2021).

Intraventricular conduction defectsFor intraventricular conduction defects, whose cataloguing in the EPPICs is highly variable and which range from bundle branch conduction disorders to alternating bundle branch block, the use of pacemakers capable of maintaining AV synchrony stagnated and DDD/R pacing was the most commonly used pacing mode (66.3% of interventions). Other pacing options for this conduction disorder were CRT-P pacing with atrial lead, at 7.2% of procedures, VDD/R, at 2.1%, and VVI/R, at 23.3%.

By age, the most commonly used mode continued to be DDD/R in both individuals older than 80 years (75.8%) and in those younger than 80 years (52.9%). Even so, the number of patients receiving devices not capable of maintaining AV synchrony was high, at 37% of individuals younger than 80 years and 13.7% of those 80 or older. VDD/R pacemaker implantation for this conduction disorder also continued its decrease, falling to 2.1% of procedures, but it comprised just 0.8% of implants in patients ≤ 80 years (table 2).

CRT-P represented 8.1% of implants for this disorder, 6.4% in patients older than 80 years, and 10% in those younger than 80.

Sick sinus syndromeAs usual, patients with SSS were divided between those who theoretically are in permanent AF or atrial flutter and have bradycardia and those who are in sinus rhythm. In this way, the aim was to evaluate the adherence of the pacing modes to the current recommendations in the clinical practice guidelines.11,12

1. Sick sinus syndrome in permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia. VVI/R pacing predominated and was used in 92.1% of all implants. A system capable of maintaining AV synchrony was used in 7.6% of implants, mainly DDD/R (6.4% of cases). It is assumed that the use of this pacing mode is because an at least partial return to sinus rhythm was expected in many of the patients

2. Sick sinus syndrome in sinus rhythm. For this condition, the number of implants capable of maintaining AV synchrony was similar to that of 2021. Accordingly, DDD/R pacemakers were implanted in 73.2% of cases and VVI/R in 24.7%. As in previous years, the low uptake is notable of AAI/R pacing in the data submitted, with only 10 patients (slightly more than 1% of the total with this indication), and the other pacing modes were rarely used, with less than 1%.

The electrocardiographic manifestation is one of the key factors when the pacing mode device is being chosen. Thus, in subgroup E2 of the EPPIC (bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome), single-chamber VVI/R pacemakers represented 34.8% of all implants and 50% of implants in individuals older than 80 years, whereas this device type was implanted in 19.6% of procedures for the remaining conditions. The number of VVI/R pacemaker implants may be inflated by the erroneous inclusion of patients with AF or permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia in this subgroup.

A breakdown of the SSS data from patients in sinus rhythm by age revealed differences in the devices used, with greater implementation of dual-chamber pacing in younger patients and men. In patients ≤ 80 years, DDD/R pacing comprised 81.6% and VVI/R mode just 14.5%. In contrast, VVI/R was used in 38.2% of procedures in patients older than 80 years (table 2).

Regarding sex and SSS, the differences in pacing mode chosen decreased considerably in 2022. Women more commonly received single-chamber VVI/R pacing than men: 24.4% vs 22.7% (27.5% vs 19.7% in 2021). The difference also decreased between patients older than 80 years, with VVI/R pacing used in 38% of women and in 34% of men (40.4% vs 28.8% in 20217).

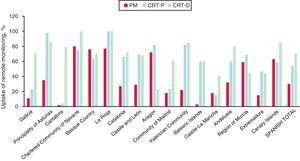

Remote monitoringIn 2022, remote monitoring was included in 35% of pacemakers, 55% of CRT-P devices, and 70% of CRT-D devices. By autonomous community, Navarre, the Basque Country, and La Rioja stood out with more than 60% of their devices included in this follow-up system, whereas less than 20% of pacemakers and CRT-P devices were included in this system in Cantabria and Castile-La Mancha (figure 8).

DISCUSSIONCompared with 2021, 5.1% fewer procedures were reported to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2022, a decrease that was probably related to an already resolved logistical problem affecting card management. Despite this decrease, the inclusion of procedures in the CardioDispositivos platform increased by 11% and reached 9407 procedures.9 This increase was largely due to integration/migration from other platforms or databases, which increased by 65.5% vs 2021. The mandatory inclusion of data from CardioDispositivos will help us to obtain a pacemaker identification card for patients endorsed by the Spanish government, as well as a high-quality registry and a rigorous surveillance system for implanted material. Accordingly, the Spanish Pacemaker Registry considers essential the participation in the platform of as many centers as possible. For this reason, we are attempting to facilitate the inclusion of procedures via the above-mentioned integration and migration processes, as well to empower the direct entry of data by implanting centers.

In 2022, the number of conventional pacemakers implanted in Spain increased by 5.6%, reaching a rate of 866 units/million population. The autonomous communities with the most aged populations continued to implant most devices (Galicia, Asturias, and Castile and León). Based on the European data for 2022, the conventional pacemaker rate in Spain (1001 units/million population) is below the European average and there is no clear relationship between the implantation rate and the per capita income in the different countries. Germany and Italy stand out with 1206 and 1207 units/million population, respectively, while our neighboring country Portugal has a rate of 1130 units/million population. The United Kingdom, Ireland, and Hungary are the countries with the lowest implantation rates (775, 728, and 593 units/million, respectively).

Compared with 2021,7 CRT use increased by 9.8% in 2022, particularly due to CRT-P, which showed a 16% increase vs the 8.9% increase seen for CRT-D. CRT-P devices recovered the upward trend of previous years, after a slight decrease in 2021 that was probably attributable to the emergence of conduction system pacing. Nonetheless, the CRT-P rate continued to be markedly lower than the European average reported by Eucomed (69 units/million population) and only exceeded that of countries such as Poland and Greece, with 32 and 11 units/million. The United Kingdom stands out with a CRT-P rate of 107 units/million population, a striking figure given the low rate of conventional pacemakers implanted; no explanation has been found for this finding. Regarding conduction system pacing in Spain, the CardioDispositivos platform now allows the possible inclusion of the pacing area (bundle of His, left branch, deep septal area),9 and we thus hope to have more information on this type of pacing in the coming years. Nevertheless, for a deeper understanding of the implementation of this pacing mode in Spain, we have created a physiological pacing registry, which already has 17 participating centers and 1346 procedures included from April 2021 to April 2023.13 The growing evidence supporting this therapy in the conventional pacing field and in patients with an indication for cardiac resynchronization, as well as the better characterization of the technique and the criteria for conduction system capture, are contributing to its exponential growth in Spain and our neighboring countries.14–17

Leadless pacemaker implantation maintained the progressive increase of recent years, with a 25% increase vs 2021. The recently published consensus document expanded the range of indications vs the latest European pacing guidelines and recommends leadless pacemakers in patients with 2 or more risk factors for infection, difficult vascular access or risk of tricuspid valve dysfunction, patients in AF or sinus rhythm with complete or paroxysmal AVB, and with no need for highly frequent follow-up.18 The distribution of this therapy varies among the autonomous communities, as in previous years, with Madrid, Galicia, and Catalonia encompassing 62% of implants. This heterogeneity can probably be explained by differences in economic and administrative management and, in any case, the elevated cost vs conventional pacing continues to be one of the main limitations for the application of this therapy.

The implanted patient profile is still that of an elderly patient (53.3% of patients are older than 80 years), mainly male and with conduction system fibrosis related to advanced age, although there is room for iatrogenic causes related to transcatheter aortic valve implantation, reported in 2.5% of cases. In terms of implanted material, there were no major differences from previous registry reports,7 with predominance of bipolar leads in the RV and LV and of quadripolar leads in the coronary sinus, as well as MR-compatible material in most leads and generators.

Regarding the pacing mode, pacing capable of maintaining AV synchrony continued to predominate in AVB, although there was a slight decrease vs 2021,7 from 77.5% to 75.5%, and DDD/R mode stood out (69.3% of procedures). In addition, the data revealed growth in the use of single-chamber pacemakers for this condition, particularly in patients older than 80 years, who showed an increase of more than 5%, from 35.8% of procedures to 41.8%, despite the loss of the benefit of being able to maintain AV synchrony (which is associated with better functional class and exercise capacity, as well as a lower incidence of AF and pacemaker syndrome19). Possible explanations include greater availability and experience with VVI/R leadless pacemaker implantation or the progressive aging and frailty of the population. We once again saw a gradual fall in the use of VDD/R pacemakers, which is probably associated with their limitations related to their inability to conduct atrial pacing if sinus node dysfunction develops or their habitual undersensing. In Spain, they were used in 5.4% of all procedures, particularly for generator replacements (11.2%), vs 3.5% for first implants.

In patients with SSS without atrial arrhythmias, pacemakers capable of atrial pacing predominated, with percentages similar to those of 2021; DDD/R was standard (73.2% of patients). The limited implementation of AAI/R pacing continued, with very low levels in Spain. As mentioned above, about one-third of implants for SSS had bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome, which may help to explain the high percentage of single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R). In the remaining patients, the clinical practice guidelines recommend DDD/R mode in SSS due to its ability to reduce the incidences of AF, stroke, and pacemaker syndrome.11,12

Differences persist between men and women, and devices capable of maintaining AV synchrony were more common in men. Nonetheless, this gender gap has considerably narrowed, which is probably related to the greater sensitivity of such implants. For example, women with SSS more frequently received VVI/R pacemakers than men, but the difference was about 2%, vs a difference of almost 8% in 2021.7

After the growth experienced during the pandemic, the use of remote monitoring programs stabilized, with no increase in 2022 from the previous year. The autonomous communities show considerable variability, and the logistics required to provide the remote monitoring service is probably one of the factors limiting its application. The main advantages of remote monitoring are the reduction in in-person visits and the possible early detection of events.20

LimitationsThe interpretation of the data received is complicated by the heterogeneity of the information sources and the high percentage of missing data for different registry parameters. Accordingly, the main area for improvement continues to be the correct and exhaustive submission of data to the CardioDispositivos platform.

CONCLUSIONSIn 2022, the number of conventional pacemakers implanted increased by 5.6%, particularly CRT, mainly due to a 16% increase in the use of CRT-P devices. Leadless pacemaker implantation grew once again, and remote monitoring stabilized as a key follow-up mode. Conduction system pacing is now a reality in our laboratories and exponential growth is expected in the coming years. The number of procedures entered in the CardioDispositivos platform9 increased by 11% (particularly migration/integration procedures from other platforms) but the sample volume fell. Progress in the implementation of measures increasing platform use is required to improve registry quality.

FUNDINGFor the maintenance and collection of the data included in the present registry, the Spanish Society of Cardiology has been supported by a grant from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS), the proprietor of these data.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSM. Pombo Jiménez conducted the data collection and drafted the sections on overall implant data and demographic and clinical data, and coordinated the work. J. Chimeno García edited the pacing mode section and performed the critical revision and final approval. Ó. Cano Pérez contributed to the critical revision and final approval. V. Bertomeu performed the critical revision and final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.