This article presents the annual activity report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) for the year 2022.

MethodsAll Spanish centers with catheterization laboratories were invited to participate. Data were collected online and were analyzed by an external company in collaboration with the members of the board of the ACI-SEC.

ResultsA total of 111 centers participated. The number of diagnostic studies increased by 4.8% compared with 2021, while that of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) remained stable. PCIs on the left main coronary artery increased by 22%. The radial approach continued to be preferred for PCI (94.9%). There was an upsurge in the use of drug-eluting balloons, as well as in intracoronary imaging techniques, which were used in 14.7% of PCIs. The use of pressure wires also increased (6.3% vs 2021) as did plaque modification techniques. Primary PCI continued to grow and was the most frequent treatment (97%) in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Most noncoronary procedures maintained their upward trend, particularly percutaneous aortic valve implantation, atrial appendage closure, mitral/tricuspid edge-to-edge therapy, renal denervation, and percutaneous treatment of pulmonary arterial disease.

ConclusionsThe Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry for 2022 reveals a rise in the complexity of coronary disease, along with a notable growth in procedures for valvular and nonvalvular structural heart disease.

Keywords

One of the most important tasks of the steering committee of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) is to record and produce an annual report on interventional cardiology activities across Spain. The association has been doing this now for over 3 decades.1–32 The ACI-SEC Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry provides an overview of the current situation in Spain and also shows changes over time as new techniques are adopted. The reports also help identify regional differences and facilitate comparisons with other countries. Although participation in this national registry is voluntary, most hospitals, both in the public and private sector, are cognisant of the importance of the data and have made it an annual tradition to submit information. Because the data are not audited, the registry has several limitations. Nonetheless, it contains vital information. The fields to be completed are updated annually to reflect the emergence of new procedures or devices. The database is managed externally by an independent company that supplies the data to the ACI-SEC steering committee for cleaning. The registry was presented at the ACI-SEC conference held in Santander, Spain, on June 9, 2022.

In short, the Spanish Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry is one of the most important initiatives of the ACI-SEC each year: it is an exercise in collaboration and transparency, and sheds light on the latest trends in interventional cardiology in Spain and enables comparison across the country's different regions. The registry is also important as it can help inform investment policies by highlighting the need to promote certain procedures in given geographic areas.

In this article, we present the 32nd report on interventional cardiology in Spain in 2022.

METHODSThe ACI-SEC registry contains data on interventional cardiology activity undertaken in most public and private hospitals in Spain in 2022. The registry describes diagnostic and therapeutic procedures performed for cardiovascular and other diseases in catheterization laboratories across the country. Data are submitted to the registry on a voluntary basis and are not audited. An implicit margin of error is, therefore, expected. When anomalies are detected, the corresponding hospital is contacted for clarification. Data are submitted via an online form updated by the ACI-SEC steering committee each year to cover new techniques and devices. In 2022, this task was undertaken, for the first time, in conjunction with the person responsible for the Spanish Congenital Heart Disease Registry to ensure a more global vision of congenital heart conditions. The data on interventional cardiology activity in Spain for 2022 were analyzed by an external company aided by a member of the steering committee, who then collated the information and compared it with findings from previous years. As in other years, population rates for Spain and each autonomous community were calculated using data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics website.33 The total Spanish population for 2022, 47 615 034 inhabitants, was used to calculate rates per million population. Data are expressed as numbers and percentages.

RESULTSInfrastructure and resourcesOf the 122 centers invited to contribute to the ACI-SEC Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry in 2022, 111 (91%) submitted data. The response rates were 96.4% (80/83) for public centers (down 3 from 2021) and 79.5% (31/39) for private centers (down 7 from 2021). This lower participation should be borne in mind when comparing activity with that reported for 2021. The data submitted corresponded to 263 catheterization laboratories. Of these, 153 were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 60 were shared, 33 were hybrid, and 17 were affiliated (overseen by another hospital with surgical backup).

Ninety-seven of the 111 hospitals offered a 24/7 infarction code service. The other 14 performed primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) during standard working hours only. The number of interventional cardiologists reported was down from 494 in 2021 to 459 in 2022. Of these 437 (95.2%) had ACI-SEC accreditation. The drop in the number of interventional cardiologists contrasts with the increase in both cardiology fellows (up from 1841 in 2021 to 2137 in 2022) and cardiologists employed under a grant scheme (66 in 2021 vs 94 in 2022). The percentage of female interventional cardiologists, at 24.2%, was similar to that reported for 2021. There was a slight increase in the number of registered nurses (735 vs 722) and a slight decrease in that of diagnostic radiographers (94 vs 106).

Diagnostic activity and coronary interventionsDiagnostic activityThe return to normal activity following the COVID-19 pandemic perceived in 202129–31 was confirmed by the data submitted in 2022. There were 165 235 interventional diagnostic procedures, representing a 4.8% increase with respect to 2021 and outnumbering for the first time the procedures performed in 2019 (165 124). The most common procedure was coronary angiography (92.8%), followed by right heart catheterization (5%) and endomyocardial biopsy (1.1%).

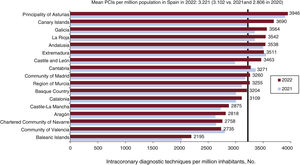

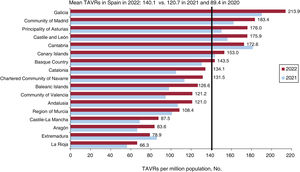

The most commonly used access site for diagnostic procedures continued to be radial access (94.9%) and PCI (92.8%). The number of coronary angiograms reported for Spain overall was similar to that in 2021, with a mean of 3221 per million population. The largest increases were observed in the Canary Islands and Castile and León (figure 1). There was notable growth in the number of cardiac computed tomography studies, which stood at 19 657 vs 14 568 in 2021. Cardiologists participated in these studies in 37 (36.6%) of the 101 centers where this procedure is available.

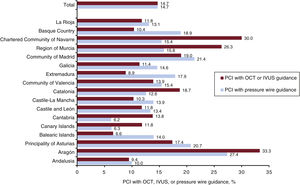

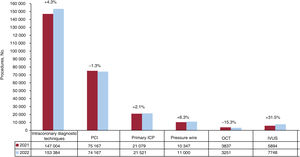

Intracoronary diagnostic techniquesThe use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques has increased steadily over the past decade (figure 2). Pressure wire functional studies were up 6.3% compared with 2021, and for the first time, centers provided data on microcirculation and vasospasm studies. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) increased by 31.5%. Some but not all of this increase can be attributed to the 15.3% drop in optical coherence tomography (catheter supply chain outages started in April 2022). Overall, intracoronary imaging (IVUS and optical coherence tomography) was used in 14.7% of PCIs, up from 11.6% in 2021. Use of these imaging techniques was unevenly distributed across the country, with Aragon in pole position (figure 3).

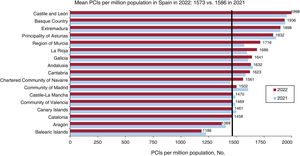

The number of PCIs remained stable, further confirming recovery of normal operations in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 74 894 procedures were performed in 2022 vs 75 167 in 2021. The mean for Spain overall was 1573 PCIs per million population, which was slightly lower than the rate of 1586 per million population reported for 2021. The highest rates were observed in Castile and León, the Basque Country, and Extremadura (figure 4). Twenty-three (20.9%) of the 111 centers submitting data to the registry performed more than 1000 PCIs in 2022, while 53 (48.2%) performed between 500 and 1000. The rest (30.9%) performed fewer than 500 procedures. The total number of unprotected left main coronary artery and chronic total occlusion interventions increased by a respective 22% and 7.2% from 2021 to 2022.

Drug-eluting stents accounted for 97.3% of all stents used in 2022. This percentage is very similar to figures reported in recent years. The use of drug-eluting balloons continued to rise; in 2022, 2891 PCIs were performed exclusively using these devices (2006 in 2021).

Calcified plaque modification strategies continued to gain traction. The year-on-year increase was 48.7% for coronary intravascular lithotripsy and 48.9% for coronary laser atherectomy. For the first time ever, centers included orbital atherectomies, with 158 procedures reported. Notwithstanding these increases, rotational atherectomies saw a 6.5% rise.

Assist devices were used in 2.1% of all PCIs, confirming the upward trend observed in 2021. A very slight increase in the number of Impella devices (Abiomed, USA) used was reported (up by 2 from 325 in 2021). Larger increases were observed for extracorporeal membrane oxygenators (181 vs 168) and intra-aortic balloon pumps, which took top position and reversed the downturn observed in 2021 (1032 pumps in 2022 vs 924 in 2021 and 1020 in 2020).

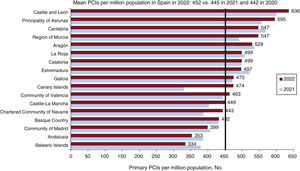

PCI for acute myocardial infarctionPCI for acute myocardial infarction increased slightly yet another year (up 0.8% from 2021), with the number of procedures coming close to prepandemic figures (22 163 in 2022 vs 22 529 in 2019).29–31 Primary PCIs accounted for 97% of all PCIs and grew by 2.1% from 2021 to 2022. Rescue and facilitated PCIs, by contrast, fell by 15.8% and 40.3%, respectively, from 2021 (figure 5). The mean number of PCIs per million population increased slightly from 445 per million population in 2021 to 452 per million population in 2022 (figure 5). Most autonomous communities reported an increase in primary PCIs. The number of primary interventions performed per center was quite evenly distributed and similar to that in 2021, with 24.8% of centers performing 300 or more primary PCIs, 22.9% between 200 and 299, 19.3% between 100 and 199, and 33% fewer than 100.

A radial access site was used in 92.4% of primary PCIs. Thrombus aspiration was used in 33.7% of procedures, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa in 17.8%, and cangrelor in 3%. Overall, 7.2% of patients developed cardiogenic shock within 24 hours of the procedure and 3.6% required hemodynamic support.

Structural interventionismAortic valve interventionsTranscatheter aortic valve replacements (TAVRs) continued to rise, with 6672 procedures performed in 2022 vs 5720 in 2021 (16.6% increase). The number of implants per million population also increased, from 120.7 replacements per million population in 2021 to 140.7 per million population in 2022 (figure 6). The increase was observed in practically all the country's autonomous communities, with Galicia and Madrid at the top (213.9 and 181.9 implants per million population respectively) and Extremadura and La Rioja at the bottom. Overall, 27.8% of centers performed fewer than 100 TAVRs in 2022, 20.4% performed 50 to 99 and 51.8% performed fewer than 50; 85.2% of procedures were performed in patients aged 75 years or older. On stratifying the patients by risk profile, 12.9% were low risk, 30% were intermediate risk, and 35.8% were high risk. The remaining 21.3% had a contraindication for TAVR. In total, 272 valve-in-valve procedures were reported in 2022, up from 197 in 2021. A percutaneous transfemoral access route was used in 94.6% of TAVRs. The other routes were surgical transfemoral (2.3%), surgical transaxillary (1.8%), transapical (0.6%), percutaneous transaxillary (0.5%), and transcaval (0.1%). The following valves were used a) Edwards (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) (in 36.4% of procedures), b) Evolut (Medtronic, USA) (33.6%), c) Acurate Neo (Boston Scientific, USA) (13%), d) Navitor (Abbott Medical, USA) (10.2%), e) Allegra (Biosensors, Singapore) (3.5%), and f) MyVal (Meril, India) (3.3%).

Mitral and tricuspid valve interventionsMitral valvuloplasty continued the downward trend observed over the past decade, with 143 procedures performed in 2022 vs 187 in 2021.

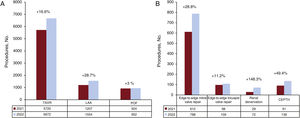

Edge-to-edge mitral valve repairs increased by 22.3%, with 782 procedures performed in 2022 vs 612 in 2021. The Mitraclip device (Abbott Medical, USA) was used in 89.1% of repairs and the Pascal Precision system (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) in 10.9%. Overall, 46% of centers performed fewer than 10 procedures, 30% performed 10 to 19, 12% performed 20 to 29, and 12% performed 30 or more. Edge-to-edge mitral valve repairs were most common in Catalonia, Andalusia, and Madrid. The procedure was used to treat functional mitral regurgitation in 24.3% of cases, organic regurgitation in 48.9%, and functional and organic regurgitation in the remaining 26.8%.

Percutaneous tricuspid valve repairs also increased significantly in 2022 (213 interventions). The most common procedures were edge-to-edge repairs (51%), bicaval valve implantation (29%), and annuloplasty with the Cardioband system (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) (11%). There were 109 edge-to-edge repairs (98 in 2021), 62 bicaval valve implantations (38 in 2021), 24 annuloplasties with the Cardioband system (18 in 2021), and 14 tricuspid valve-in-valve replacements (15 in 2021).

Paravalvular leak closureIn total, 180 paravalvular leak closures were performed in 2022, down from 195 in 2021. The registry also showed an increase in aortic valve repairs (70 in 2022 vs 56 in 2021) and a decrease in mitral valve repairs (110 vs 139).

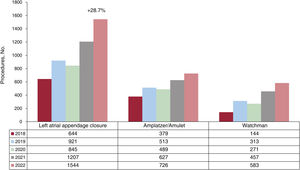

Nonvalvular structural interventionsLeft atrial appendage closure once again showed the greatest growth (figure 7), with 1544 procedures in 2022 vs 1207 in 2021 (increase of 28.7%). The most widely used closure device was Amulet (Abbott Vascular, USA), used in 726 patients, followed by Watchman FLX (Boston Scientific, USA) (n = 583), Lambre (Lifetech Scientific, USA) (n = 203), and Omega (Vascular Innovations, Thailand) (n = 32).

There was also a notable increase in renal denervations (72 in 2022 vs 25 in 2021). Other nonvalvular structural interventions included 124 percutaneous procedures to treat acute pulmonary thromboembolism (44 with specific devices) and 136 to treat chronic thromboembolic disease (91 in 2021).

Adult congenital heart disease interventionsAs previously mentioned, the collection procedure for congenital heart disease interventions was optimized in 2022. In brief, the most common procedures used to treat congenital heart disease in adults all increased, with 952 patent foramen ovale repairs (924 in 2021), 73 aortic coarctation repairs (58 in 2021), and 351 atrial septal defect repairs (331 in 2021). More details will be provided in the Spanish Congenital Heart Disease Registry report.

DiscussionThe ACI-SEC Spanish Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry reveals a number of remarkable findings for 2022. First, the latest report confirms a return to normal hospital activity in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the overall number of interventional cardiology procedures exceeding those reported for 2019. Second, the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques, including functional tests with a pressure wire, also increased, and for the first time ever, centers submitted information on microcirculation and vasospasm studies. Third, there was an overall increase in intracoronary imaging techniques, in particular IVUS. Fourth, the upward trend for PCI assist devices, in particular intra-aortic balloon pumps, was maintained; the use of Impella devices and extracorporeal membrane oxygenators also increased but less so. Fifth, structural heart disease procedures continued a strong upward trend, with pronounced increases in TAVR, mitral valve repairs, and left atrial appendage closures. Sixth, renal denervations made a comeback, and there was also a marked increase in percutaneous treatments for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Finally, the use of treatments with a proven prognostic impact, such as primary PCI and TAVR, continued to vary across the different regions of Spain.

The 2021 ACI-SEC report showed that hospitals had resumed near-normal operations in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.31 This recovery was confirmed by the 2022 report, with similar and in some cases even higher procedure volumes than those reported in 2019.31

The number of centers participating in the registry fell, an important consideration when comparing data from 2022 and 2021. Nevertheless, most of the hospitals invited to participate responded, and we believe that the data provide an accurate picture of interventional cardiology activity in Spain for 2022. Considering that overall activity increased from 2021 to 2022, we were surprised to see a decrease in the number of interventional cardiologists and an increase in that of cardiology fellows.

A number of aspects are worth highlighting in the area of coronary procedures. Radial access continued to dominate, accounting for almost 95% of all access sites used in both diagnostic procedures and PCI. Intracoronary imaging-guided PCI and invasive functional studies (with the first-ever reports of the use of microcirculation and vasospasm procedures) experienced further growth in 2022. The evidence on the usefulness of these procedures is growing, but uptake is probably also up due to a greater awareness of their benefits among interventional cardiologists34 and an increase in the number of complex heart conditions. These circumstances may also have influenced the marked increase observed in calcified plaque modification procedures, for which there is a growing body of information.35 There was also a notable increase in left coronary artery PCIs from 2021 to 2022 and a more modest increase in chronic total occlusion repairs. The growth in drug-eluting balloon angioplasty is also remarkable.

The use of rescue and facilitated PCIs for acute myocardial infarction increased at different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic,30 but this trend was reversed in both 2021 and 2022. The volume of primary PCI activity largely returned to prepandemic levels.29 Although most autonomous communities reported a growth in primary PCI activity, significant regional disparities persist (figure 5), despite clear evidence of the positive impact of this procedure on prognosis.36 Targeted strategies to increase uptake in areas with low volumes of activity may be worth considering.

New records were set for percutaneous treatments for structural heart disease,1–31 with significant increases observed for all procedures compared with 2021. The growth of TAVR activity seems to be unstoppable, with a 16.6% increase vs 2022. The rate per million population also increased significantly (from 120.7 per million population in 2021 to 140.1 per million population in 2022) (figure 6), and is now close to the European mean.37 Although TAVRs increased in practically all the autonomous communities of Spain, significant regional differences remain.

Percutaneous treatment of mitral regurgitation showed one of the steepest growths with respect to 2021, confirming yet again the recovery of normal operations following the COVID-19 pandemic.31 This recovery, together with growing evidence on the benefits of this technique,38 has cemented the use of edge-to-edge mitral valve repairs in Spain, although, again, activity varies across both regions and centers. Tricuspid regurgitation treatments also increased in 2022. Edge-to-edge repair continues to be the most widely used technique,39 but there was also a growth in bicaval prostheses and percutaneous annuloplasties.

Of note, some of the largest increases compared with previous years were observed for percutaneous left atrial appendage closures, renal denervations, and percutaneous treatment of chronic pulmonary thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (figure 8 and figure 9). The data for 2022 confirm that left atrial appendage closure has come of age and is being increasingly embraced by interventional cardiologists in Spain. The growth can probably be attributed to greater experience and stronger evidence.40–42 Renal denervation is undergoing something of a revival, most likely driven by recent recommendations.43 Finally, percutaneous treatment of pulmonary artery disease deserves a separate mention. Although the volume of acute pulmonary thromboembolism treatments was similar to that in 2021, there was a notable increase in the use of specific devices, a trend that is likely to continue.44,45 Percutaneous treatments for chronic thromboembolism pulmonary hypertension also increased in number. Considering the lack of sufficiently powered randomized trials, this increase may be partly due to experience accumulated in recent years46 and the inclusion of more centers offering this treatment.

Overview of noncoronary procedures in 2022 vs 2021. A: TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) and left atrial appendage (LAA) and patent oval foramen (POF) closures. B: edge-to-edge mitral and tricuspid valve repair, renal denervation, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

This latest report on the Spanish Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry confirms that Spanish hospitals have resumed normal operations in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. It also shows that an increase in more complex heart conditions and structural interventions, with the main procedures in this area reaching record numbers.

FUNDINGThis study received no funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll the authors contributed to writing and critically reviewing this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTX. Freixa is a proctor for Abbott Medical and Lifetech Science; A. Jurado-Román is a proctor for Boston Scientific, World Medica, Philips-Biomenco, and Medtronic; and I. Cruz-is a proctor for Abbott Medical, Lifetech Science, and Boston Scientific.

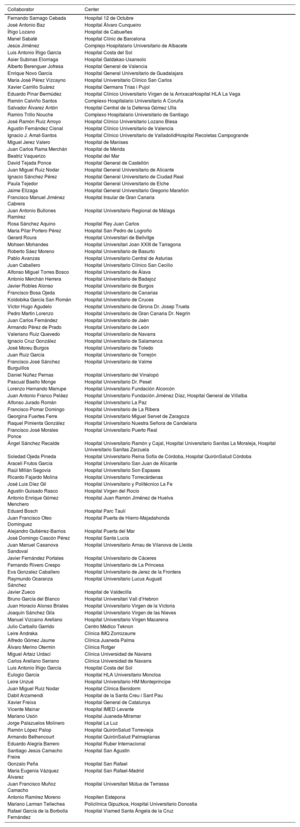

| Collaborator | Center |

|---|---|

| Fernando Sarnago Cebada | Hospital 12 de Octubre |

| José Antonio Baz | Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro |

| Íñigo Lozano | Hospital de Cabueñes |

| Manel Sabaté | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

| Jesús Jiménez | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete |

| Luis Antonio Íñigo García | Hospital Costa del Sol |

| Asier Subinas Elorriaga | Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo |

| Alberto Berenguer Jofresa | Hospital General de Valencia |

| Enrique Novo García | Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara |

| María José Pérez Vizcayno | Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos |

| Xavier Carrillo Suárez | Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol |

| Eduardo Pinar Bermúdez | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la ArrixacaHospital HLA La Vega |

| Ramón Calviño Santos | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña |

| Salvador Álvarez Antón | Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla |

| Ramiro Trillo Nouche | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago |

| José Ramón Ruíz Arroyo | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa |

| Agustín Fernández Cisnal | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia |

| Ignacio J. Amat-Santos | Hospital Clínico Universitario de ValladolidHospital Recoletas Campogrande |

| Miguel Jerez Valero | Hospital de Manises |

| Juan Carlos Rama Merchán | Hospital de Mérida |

| Beatriz Vaquerizo | Hospital del Mar |

| David Tejada Ponce | Hospital General de Castellón |

| Juan Miguel Ruiz Nodar | Hospital General Universitario de Alicante |

| Ignacio Sánchez Pérez | Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real |

| Paula Tejedor | Hospital General Universitario de Elche |

| Jaime Elizaga | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

| Francisco Manuel Jiménez Cabrera | Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria |

| Juan Antonio Bullones Ramírez | Hospital Universitario Regional de Málaga |

| Rosa Sánchez Aquino | Hospital Rey Juan Carlos |

| María Pilar Portero Pérez | Hospital San Pedro de Logroño |

| Gerard Roura | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge |

| Mohsen Mohandes | Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona |

| Roberto Sáez Moreno | Hospital Universitario de Basurto |

| Pablo Avanzas | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias |

| Juan Caballero | Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio |

| Alfonso Miguel Torres Bosco | Hospital Universitario de Álava |

| Antonio Merchán Herrera | Hospital Universitario de Badajoz |

| Javier Robles Alonso | Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

| Francisco Bosa Ojeda | Hospital Universitario de Canarias |

| Koldobika García San Román | Hospital Universitario de Cruces |

| Victor Hugo Agudelo | Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta |

| Pedro Martin Lorenzo | Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín |

| Juan Carlos Fernández | Hospital Universitario de Jaén |

| Armando Pérez de Prado | Hospital Universitario de León |

| Valeriano Ruiz Quevedo | Hospital Universitario de Navarra |

| Ignacio Cruz González | Hospital Universitario de Salamanca |

| José Moreu Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Toledo |

| Juan Ruiz García | Hospital Universitario de Torrejón |

| Francisco José Sánchez Burguillos | Hospital Universitario de Valme |

| Daniel Núñez Pernas | Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó |

| Pascual Baello Monge | Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset |

| Lorenzo Hernando Marrupe | Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón |

| Juan Antonio Franco Peláez | Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Hospital General de Villalba |

| Alfonso Jurado Román | Hospital Universitario La Paz |

| Francisco Pomar Domingo | Hospital Universitario de La Ribera |

| Georgina Fuertes Ferre | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet de Zaragoza |

| Raquel Pimienta González | Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria |

| Francisco José Morales Ponce | Hospital Universitario Puerto Real |

| Ángel Sánchez Recalde | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Moraleja, Hospital Universitario Sanitas Zarzuela |

| Soledad Ojeda Pineda | Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba, Hospital QuirónSalud Córdoba |

| Araceli Frutos García | Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante |

| Raúl Millán Segovia | Hospital Universitario Son Espases |

| Ricardo Fajardo Molina | Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas |

| José Luis Díez Gil | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe |

| Agustín Guisado Rasco | Hospital Virgen del Rocío |

| Antonio Enrique Gómez Menchero | Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez de Huelva |

| Eduard Bosch | Hospital Parc Taulí |

| Juan Francisco Oteo Domínguez | Hospital Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda |

| Alejandro Gutiérrez-Barrios | Hospital Puerta del Mar |

| José Domingo Cascón Pérez | Hospital Santa Lucía |

| Juan Manuel Casanova Sandoval | Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida |

| Javier Fernández Portales | Hospital Universitario de Cáceres |

| Fernando Rivero Crespo | Hospital Universitario de La Princesa |

| Eva Gonzalez Caballero | Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera |

| Raymundo Ocaranza Sánchez | Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti |

| Javier Zueco | Hospital de Valdecilla |

| Bruno García del Blanco | Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron |

| Juan Horacio Alonso Briales | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria |

| Joaquín Sánchez Gila | Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves |

| Manuel Vizcaino Arellano | Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena |

| Julio Carballo Garrido | Centro Médico Teknon |

| Leire Andraka | Clinica IMQ Zorrozaurre |

| Alfredo Gómez Jaume | Clínica Juaneda Palma |

| Álvaro Merino Otermin | Clínica Rotger |

| Miguel Artaiz Urdaci | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Carlos Arellano Serrano | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Luis Antonio Íñigo García | Hospital Costa del Sol |

| Eulogio García | Hospital HLA Universitario Moncloa |

| Leire Unzué | Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe |

| Juan Miguel Ruiz Nodar | Hospital Clínica Benidorm |

| Dabit Arzamendi | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau |

| Xavier Freixa | Hospital General de Catalunya |

| Vicente Mainar | Hospital IMED Levante |

| Mariano Usón | Hospital Juaneda-Miramar |

| Jorge Palazuelos Molinero | Hospital La Luz |

| Ramón López Palop | Hospital QuirónSalud Torrevieja |

| Armando Bethencourt | Hospital QuirónSalud Palmaplanas |

| Eduardo Alegría Barrero | Hospital Ruber Internacional |

| Santiago Jesús Camacho Freire | Hospital San Agustín |

| Gonzalo Peña | Hospital San Rafael |

| María Eugenia Vázquez Álvarez | Hospital San Rafael-Madrid |

| Juan Francisco Muñoz Camacho | Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa |

| Antonio Ramírez Moreno | Hospiten Estepona |

| Mariano Larman Tellechea | Policlínica Gipuzkoa, Hospital Universitario Donostia |

| Rafael García de la Borbolla Fernández | Hospital Viamed Santa Ángela de la Cruz |